Great stories can inspire us, make us better, and help us make good decisions.

Whether found in a book, a movie, or a song, a well-told story can contribute to what William Bennett defined as the purpose of an education: “the architecture of souls.”

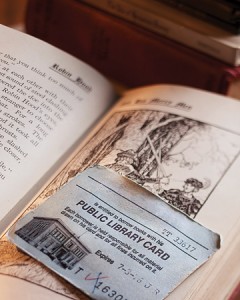

I grew up in a house that loved stories. My mother took us to the library every week. When she gave me my first library card, she bent down to my eye level, handed it to me gently, and said, “As long as you have this library card, you will always have a friend.”

My parents’ love of stories was not limited to literature. My father, whose parents emigrated from Ireland, thought the answer to every one of life’s important questions could be found in the lyrics of an Irish song. We were the first house in our neighborhood to get cable TV. And we always went to the movies as a family.

A few years after college I began volunteering with a group that tutored children in some of Boston’s poorest neighborhoods. There, I learned even more about the transformational power of stories.

Before diving into math or English, I would break the ice those Saturday mornings by asking my students what they had done the night before. Invariably, they had gone to a movie or watched something on television. One morning a couple of girls mentioned they had seen Titanic. The next week they had seen it again. And the next week something incredible happened: They did not watch television or go to the movies. They went to a museum to see an exhibit on the Titanic. They learned about the people on the ship and how the ship was made. They plunged their hands into water the same temperature as the Atlantic that tragic night.

Then those girls started to do something none of their school textbooks had succeeded in getting them to do—they began to ask the big questions: What would I do in that situation? Would I be brave? Would I be a coward? Because of a movie, these girls were now on the path to true learning and discovery.

A year later, another event taught me about the power of movies. On April 20, 1999, two high school students in Colorado murdered 12 of their classmates and one of their teachers. They referred to their plan as NBK in celebration of Natural Born Killers, a movie they had watched about serial killers. They dressed in black trench coats in honor of another film, the Basketball Diaries, in which the lead character fantasized about donning a black trench coat and murdering his classmates.

Stories from that fateful day in Colorado—including the declaration of belief in God from a student threatened by a gunman—awakened me to my lack of faith. I admitted that God was God, and I began to read the Bible. And I noticed something: Jesus loved stories. This was reflected in the way he answered questions people asked him, such as with the parable of the good Samaritan.

Twenty centuries later, the stories of Jesus remain with us. So, in prayer, I turned for answers to the same first-century rabbi. And I realized that He answers us in the same way—in parables, in the stories He writes in our lives. I began to see how seemingly disparate experiences in my life—listening to Irish music with my father, watching movies with my brothers, reading books with my mother, and teaching students in Boston—began to fit together like pieces of a puzzle. Many of the films and books and songs I had loved growing up were gently pointing me toward God.

No longer did I see my loves for teaching and film as separate things. I saw them as mutually reinforcing. Inspired by my newfound faith and supported by my hard-working wife, I started a film company to inspire people to ask the big questions and set them on a path for truth. Great films could help accomplish what William Bennett called the purpose of education—“the architecture of souls.”

I hope we’ll each find time to enjoy great stories. And through these stories—and daily prayer—I hope that we will follow the story God has written for each of us.

Micheal Flaherty is president of Walden Media, which has produced such movies as Charlotte’s Web, Amazing Grace, and the Chronicles of Narnia series. This essay is adapted from a BYU forum address delivered March 15, 2011.