By Mary Lynn Johnson, ‘91

Growing up as children of a professor and then following him into the ranks of BYU faculty, Todd and Lanny Britsch have witnessed and helped to shape more than 50 years of BYU history.

It’ll be 55 years this August. Fifty-five years since Todd A., ‘62, and R. Lanier, ‘63, Britsch began returning to campus each fall. The children of a professor, both boys enrolled at the BYU elementary school in 1946. Both were hired to teach at BYU in 1966, fresh from their PhD programs. Both will retire in June 2002. And no, they’re not twins.

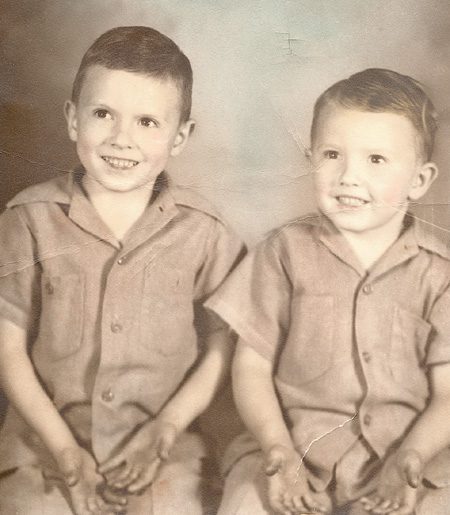

No one asks them about that any more, actually. But the question came up rather often back when the Britsch brothers were getting admitted to BYU sports events with their elementary school activity cards. They were essentially the same size for quite a while, growing up. And they have always been best friends.

Children of the Y

Their father was Ralph A. Britsch, ’33, late professor of English and humanities, who began teaching at BYU in 1938. “Dad was on the faculty I believe 37 years before he retired,” Todd says. “He saw BYU grow from fewer than 2,000 students right up to having 20-plus thousand. He saw most of the big growth of the university during his time here.”

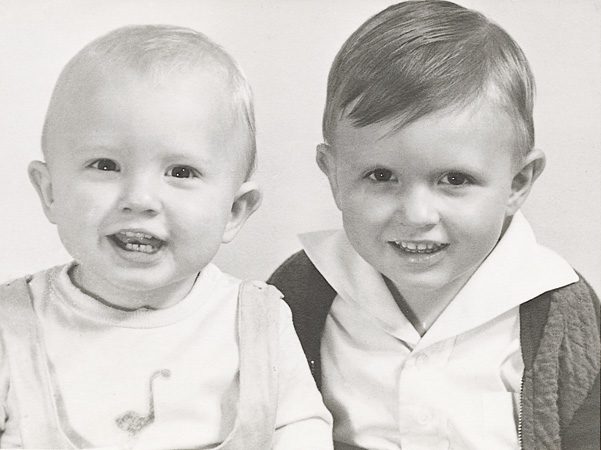

Of course his boys have witnessed it too. Lanny was born the year Ralph Britsch joined the BYU faculty; Todd was born the year before.

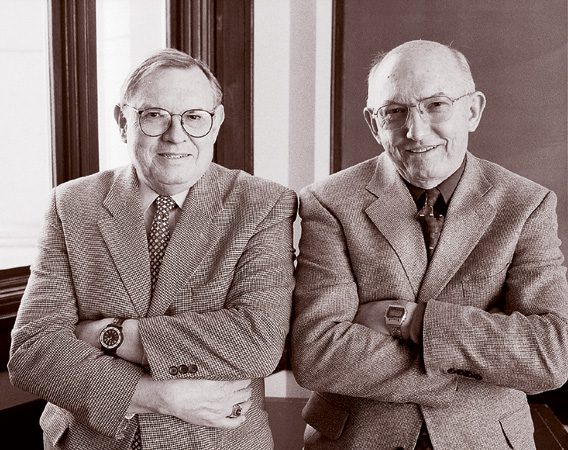

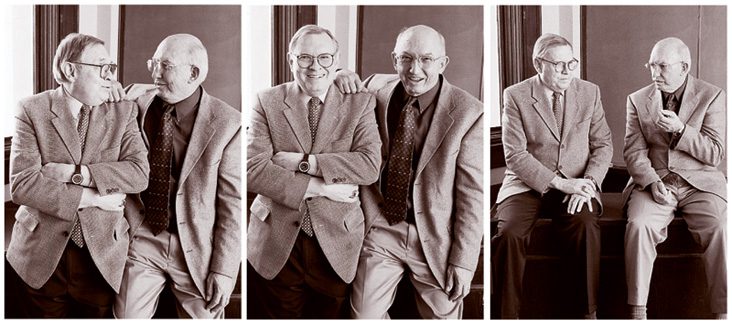

Todd (left) and Lanny Britsch began visiting campus in their early years – attending everything from church meetings to concerts to football games.

“The first memory I have of BYU is still locked in my mind,” Todd says. “We used to live down on Fourth East. I came up those stairs with my dad, and he was showing me the new building being built. That was in 1941. I must have been just about four years old, and it was the Joseph Smith Building, which has since been torn down.”

Lanny remembers doing high school projects at the Grant Library and exploring the Eyring Science Center when it was under construction, looking down through the hole where the Foucault pendulum now hangs.

“We were really raised as BYU kids,” Todd says. “I can remember coming up and rolling Easter eggs down the Maeser lawn. This was kind of a home environment for us. This was where you went to concerts, where you went to plays, where you watched football games, where you did all the kinds of things that we were interested in. Where you watched the cute girls–we did a fair amount of that, too. It seemed like all of our experiences were centered around the university.”

A Brace of Britsches

With BYU so much a part of their earliest memories, it was perhaps only natural that Todd and Lanny Britsch would choose to spend their careers on campus, contributing to the university they had learned to love as children. Both chose teaching careers not long after returning from their LDS missions.

By then there were even more Britsches on campus. “There was a time when there were four of us in college because Lanny and I went on missions and our sisters caught up with us,” Todd says. “And my dad was teaching. So we’d all pile in the car and head up to school together.”

One after another, Todd (right) and Lanny graduated from BYU Training School and B.Y. High and enrolled at BYU, where they met their spouses and chose their careers..

The Britsch sisters introduced Todd and Lanny to the women they would marry–Dorothy Crofts, ’61, and JoAnn Murphy, ’62, whom the sisters knew through their campus social unit. Interestingly, both women took classes from Ralph Britsch at one time or another.

Lanny (left), a year younger than hsi brother Todd, was born the year their father began teaching at BYU.

“Their father was a wonderful teacher,” says Todd’s wife, Dorothy. “The family’s gifted; it just seems to be in the genes.” Though none of the five Britsch children set out to become professors, all eventually did. One sister teaches at Salt Lake Community College; the other at Southern Utah University. Their youngest brother has taught at BYU–Hawaii and Grambling State University.

Teaching is a legacy for the Britsch children. “I could be anywhere in the world,” says Lanny, “and people would say, ‘Britsch. Are you related to Ralph Britsch? He was the best teacher I ever had.’ I really wish that I could leave a heritage like my father did.”

Todd, a professor of humanities, chose teaching partly because of his love for Bach’s music: “I thought, ‘He’s brought me about as much enjoyment as anything outside of my family and the Church. Why not have a career where you get to spend your time with things that you really like?'”

For Lanny, a history professor, a pivotal moment in his career path came when he was with his father and brother. “One afternoon I was in Dad’s office over in the McKay Building,” he recalls. “He and Todd had been talking about writing a western humanities text together (eventually published as The Arts in Western Culture [1984]). Having served my mission in Hawaii where there are a lot of people of Asian ancestry, I said, ‘I ought to specialize in Asian culture, and we can include the whole world.’ And my dad surprised me. He said, ‘You know, Lan, you really might want to consider that.'”

Once the brothers chose academia and embarked for graduate school, both hoped to teach at BYU. Both turned down higher-paying offers from other schools in order to join the faculty in 1966. Says Lanny’s wife, JoAnn, “They’ve had great fun being brothers together on campus.”

The three Professors Britsch made quite a team. “When I was first here, they didn’t have enough offices,” Todd says. “The humanities program was over in the McKay Building on the top floor, and my office was down in the Smith Fieldhouse. I was there up underneath the stands, by some of the coaches. In fact I put a little sign on my office: ‘Todd Britsch, Assistant Coach of Humanities.’ But going up and down wasn’t always easy for teaching my classes, so I almost camped in the outside part of my dad’s office. And we collaborated a great deal.”

They also sang together. Having grown up singing with their father in a ward chorus, the young professors became standing understudies for BYU‘s faculty quartet. Ralph Britsch directed it, and whenever one of the quartet’s official members couldn’t participate, he called on his sons. “Sometimes it was three Britsches and somebody else,” Lanny remembers.

The Britsches also played handball and later racquetball on campus two or three times a week, something they had begun as undergraduates. That continued until 1991, when Todd became, Lanny says, “an Administration Building administrator and had no control over his time.”

University Thinkers

Sometimes their commitment to BYU has taken the brothers places they would not prefer to be–namely, out of the classroom. “If I wanted to make my living being an administrator, I would work for a major corporation with the kind of salaries that they get,” Todd says with a smile.

In spite of their preference for the classroom, both Britsches were tapped for major administrative service in 1986. That’s when Todd was named dean of the College of Humanities and Lanny went to BYU–Hawaii as vice president for academics. About five years later, both brothers got new assignments.

Shortly after returning from Hawaii, Lanny became the director of BYU‘s David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies, where he served from 1991 to 1997.

“It was a great assignment,” Lanny says. “I really believe that the kind of education that’s being conveyed to students of the Kennedy Center is important. And I thoroughly enjoyed the various guests who came to campus, not only the large number of ambassadors during Utah’s centennial year back in ’96, but also a broad array of other diplomats and emissaries. It was a wonderful opportunity to introduce BYU and, indirectly, the Church.”

“Throughout Lanny’s career, especially his service in Hawaii and then again in the Kennedy Center, he’s been committed to helping BYU reach beyond the borders of the United States,” says Clayne L. Pope, ’65, dean of the College of Family, Home, and Social Sciences and a longtime colleague of both brothers. “I think he’s had a very significant influence on the internationalization of BYU over the last two decades.”

At about the time Lanny moved to the Kennedy Center, Todd became an associate academic vice president. “I actually turned that job down twice,” he says, “And then the third time I was asked I decided that apparently I had gotten the answer wrong.” He was named academic vice president a year later and served until the end of Rex E. Lee’s, ’60, administration.

“Todd had great friendship and compassion for President Lee when the president was suffering from cancer during his final years in office,” says Debra M. Petersen, ’77, who was Todd’s secretary for several years. “Todd had some of his own health challenges during that time, and there were days that he would be struggling and I’d say, ‘Why don’t you take some time off?’ He would then say something like, ‘Look at my boss down the hall. How can I leave when he stays with what he is going through?’ There was a lot of integrity there–a lot of team feeling.”

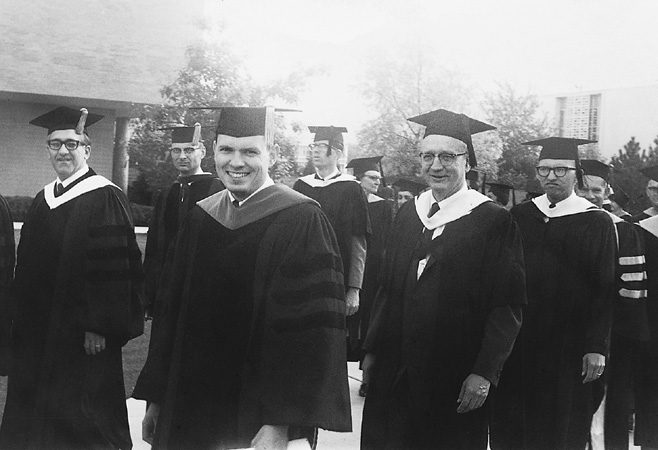

Both hired in 1966, Todd leads and Lanny follows their father, Ralph, in BYU’s 1967 faculty processional. The three Britsch professors graced BYU’s rosters fora bout 10 years before Ralph retired.

“I think Todd personifies the unusual commitment that some BYU faculty have to this university,” Pope says. “Todd is first and foremost dedicated to the growth and development of this university and its ideals. He has always sacrificed his personal interests to the larger interests of the university. And that also applies to Lanny. Both of them are unstinting in their willingness to serve.”

“Todd was much beloved as academic vice president,” says John S. Tanner, ’74, who served under Todd as an associate academic vice president from 1992 to 1998. “And even since he’s stepped down, the administration often seeks Todd’s counsel on vexing problems and requests his service on important committees. He’s got such long institutional memory and an uncommon measure of common sense, wisdom, and judgment.” Now chair of the English Department, Tanner oversaw the Kennedy Center during his term as associate academic vice president, so he also worked closely with Lanny. “Both of them are what Todd calls ‘university thinkers’–engaged in the life of the university beyond their own classrooms and their own departments,” he says.

A Sense of Mission

Despite their experience with high profile positions, both Britsches consider themselves to be, first and fundamentally, teachers.

“Todd always describes himself as a teacher,” Pope says. “I think he has helped keep BYU focused on the value and importance of good teaching, not allowing us to drift away from our obligations to our students. And he has contributed as much as anyone to the high quality of general education at BYU.”

General education courses are in fact Todd’s favorites. “I love the sophomore survey course, Humanities 201 and 202,” he says. “I tell the students it doesn’t matter whether they like it as long as they understand it and pass the tests. But if you start with the Greek sculptors and architects and playwrights and go down to the present–through Shakespeare and Goethe and Dante and Homer and, some of my favorites, Palestrina and Bach and Mozart–if you can’t find something in that to like, you’d have to be pretty dull anyway.”

Todd also loves teaching his course on the New Testament, Acts to Revelation. “That’s a very personal thing,” he says. “At a time in my life when I was struggling–it was after the death of my son, who died at age 20–I found that Paul gave me more comfort than anything else. People often talked of Paul as though it was kind of a struggle to read him. And I kept thinking, Maybe I ought to try teaching that because maybe I could convey the reason that I love this stuff so much.”

Teaching, though, is not without its challenges. Says Todd, “Working as a janitor was one of the most satisfying jobs of my life because if you give me a bucket of pine oil and a mop, I can go in there and I can guarantee you that when I come out, that is a clean rest room. When I come out of the classroom, I have no idea what’s gone on in my students’ heads.”

In their 35 years on the faculty, the Britsch brothers have literally taught generations of students. In Todd’s winter 2001 New Testament class, for example, there were six students whose parents had also been his students. In fact, Dorothy says, “Most of the people in Todd’s department were his students at one time or another.”

Lanny’s first love in teaching is “anything connected to Asian religion and thought, or Christianity in Asia,” he says. He has spent his career focusing on comparative religion and the history of religion–especially The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints–in Asia.

In 1972 Church historian Leonard Arrington asked Lanny to write what became perhaps the definitive history of the Church of Jesus Christ in Asia and the Pacific. His research eventually produced Unto the Islands of the Sea: A History of the Latter-day Saints in the Pacific (1986), Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaii (1989), and From the East: The History of the Latter-day Saints in Asia, 1851–1996 (1998). “Lanny has established a nice reputation as an expert on the Church in Asia,” Tanner says.

Lanny’s most recent book–an idea conceived for his master’s thesis decades ago and brought to fruition after a sabbatical trip through India in 1998–is Nothing More Heroic: The Compelling Story of the First Latter-day Saint Missionaries in India (1999). Given a year’s leave from BYU after his service at the Kennedy Center, he felt strongly prompted to continue his research on the missionaries sent to India in the 1850s. “I think I was supposed to write it for the descendants of those 17 missionaries and those few converts that they made in India,” he says. Lanny actually considers all of his Church history writing something of a calling. “I have felt all along that these stories need to be told because they are not known to the Latter-day Saints,” he says.

In fact, both Britsches approach their work at BYU with a sense of mission.

“Our attitude about teaching here has always been that we wanted to give our lives in service to the Church, and we’re just grateful that we can do it and be paid at the same time,” Lanny says. And, he says, he’s grateful for the environment in which he can do his work. “When I teach History 485, we talk about a lot of terms used by historians–nihilism and skepticism and cynicism, things of that kind. I can say the things I want to say in a gospel context–things that I could not say at any university in the world except in our Church system. I’ve got more academic freedom to do what I want to do here than I could ever have anywhere else.”

In 35 years on BYU’s faculty, Todd (left) and Lanny have been deans, vice presidents, and directors. But they consider themselves, first and fundamentally, to be teachers.

“I wouldn’t teach if I didn’t think it had some meaning that went beyond even the most profound experiences of this life,” Todd adds. “I’m hoping that students see a connection between things that are beautiful and things that are true and eternal. BYU is the only place that I’d have been interested in teaching at for the last 20 years because what I am interested in is what we strive for–to teach people who are disciples of Christ about things that will be important for them for eternity.”

Now in their last official year at BYU, the brothers are cherishing their final teaching opportunities. Dorothy reports that Todd recently came home and said, “It’s kind of sobering that this is the last time I’m going to be teaching Bach.” The brothers will spend some of their last months of BYU employment leading separate study abroad groups to England, something Todd and Dorothy have done three previous times.

Still, though both Britsches plan to retire in June 2002, they couldn’t leave the campus behind even if they wanted to. It’s in their bones. More than half of BYU‘s history has been flavored by the presence of Britsches. And people who have worked with Todd and Lanny believe their influence will endure far beyond their academic tenure.

“I believe that if BYU does fulfill its prophetic promise,” Tanner says, “it will be in no small measure because of people like Todd and Lanny Britsch–and it will look a lot like the BYU they have given their lives to envision and build.”