The Art of Family

The Art of Family

For James Christensen, being a successful artist required working alone. For his daughters, the same goal demands a different approach.

By Charlene Renberg Winters (BA ’73) in the Spring 2007 Issue

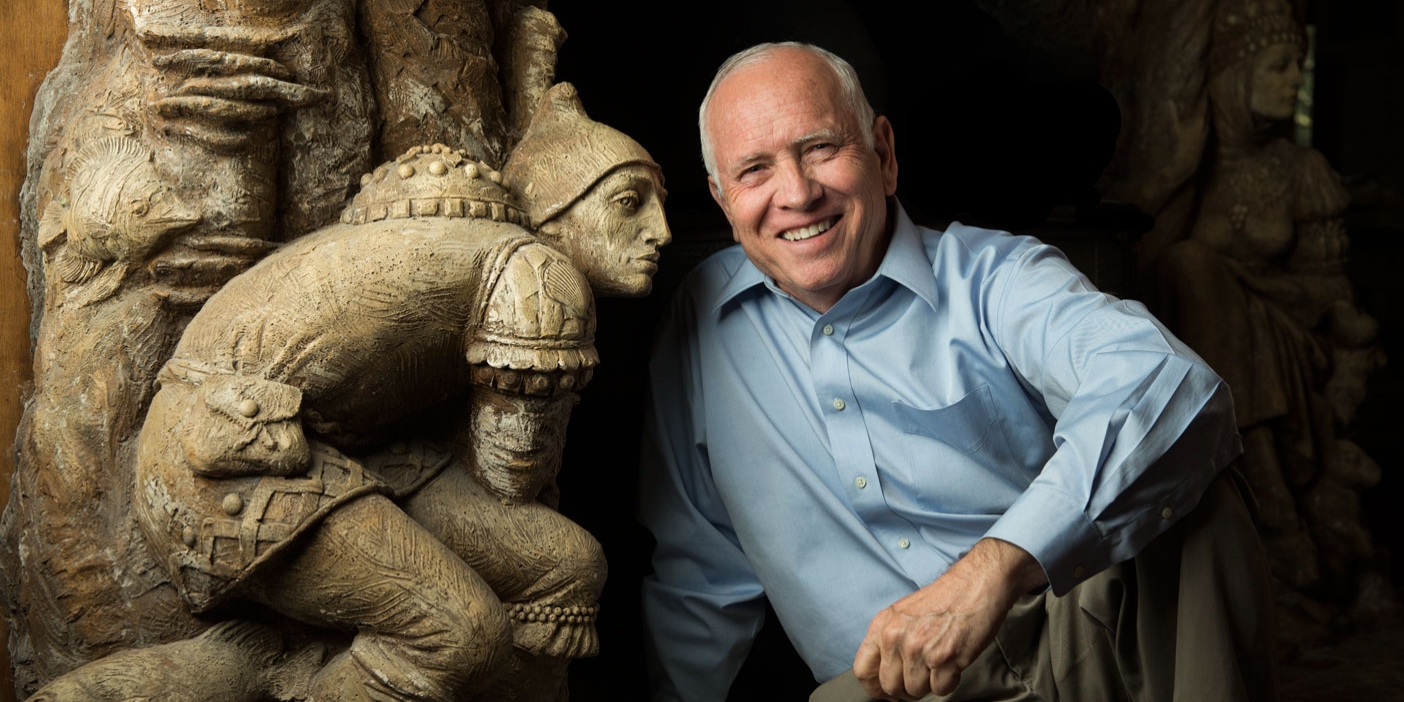

Whenever nationally recognized fantasy artist James C. Christensen (BA ’67) entered his studio to paint as his five children were growing up in their Orem, Utah, home, he would warn them, “I’m closing my door. Unless you are on fire, don’t bother to knock. You need to be in flames before you can interrupt me.”

“That’s exactly what he would say,” recalls his daughter Cassandra Christensen Barney (BFA ’95), also an artist, who now works from her own home studio in Vancouver, British Columbia. “Art was Dad’s work, and while it was intriguing, it was sacred, and we respected that.”

Privacy while painting, however, has not been an option for Barney or for her artist sister, Emily Christensen McPhie (BFA ’00). Motherhood is their top priority. With three daughters each, the artists could fight for time to paint, but neither wants to exclude her children. Instead, they have made conscious decisions to draw Sunshine, Fiona, Tallulah, Cordelia Lavender, Clover Iona, and Ezra Petunia into their studios.

“Even when I was working on my master’s degree, my space included their desk with all the paints, markers, pencils, and other art tools they wanted,” Barney says. “We refer to it as ‘our studio.’ It has become such a part of our lives that when my daughter Sunshine went to play at a friend’s home, she came home incredulous because they didn’t have an art studio.”

With their daughters by their sides, both women are experiencing considerable success as gallery artists. Barney’s works have also been made into fine art prints through the Greenwich Workshop in Connecticut, and the workshop is considering publishing art by McPhie, who works out of her home in Chandler, Ariz. As the two sisters have made their way into the art world successfully navigated by their father, they have discovered theirs to be different paths from his, and they have found themselves often standing at the intersection of art and family.

Like Father Like (or Unlike) Daughters

Jim Christensen deliberately did not thrust his children toward art as a vocation. As one who taught art at BYU for two decades, he believes being an artist requires a fire in the belly. Whenever his children had a question about art, he would answer it, but he did not impose his career choice on them. He did, however, build art into family activities and traditions. “Dad used to take us to art museums wherever we traveled, and I’m doing the same for my girls,” says McPhie. “One of the effects of being exposed to art is finding the value in it and appreciating it.”

Despite a natural and nurtured love of art, neither McPhie nor Barney planned to pursue it as a major. After exploring other options, however, both realized art was their passion.

Barney began her studies at Ricks College and later transferred to BYU. One of her challenges as a young artist, she says, was that her instructors expected her to be as good as her art-professor father. “I was just learning,” she says. “I was just a beginner, but I knew I loved it.” At BYU, Barney took several classes from her father. “When I finally got an A from him, I felt intense satisfaction,” she says. “He was a hard but helpful teacher.”

McPhie believes she was influenced by her father without realizing it. “I grew up drawing and learning about art, and when I entered BYU I just fell into it. It seemed like a natural thing to do.”

She had one class from Christensen before he retired but credits him as her lifelong teacher.

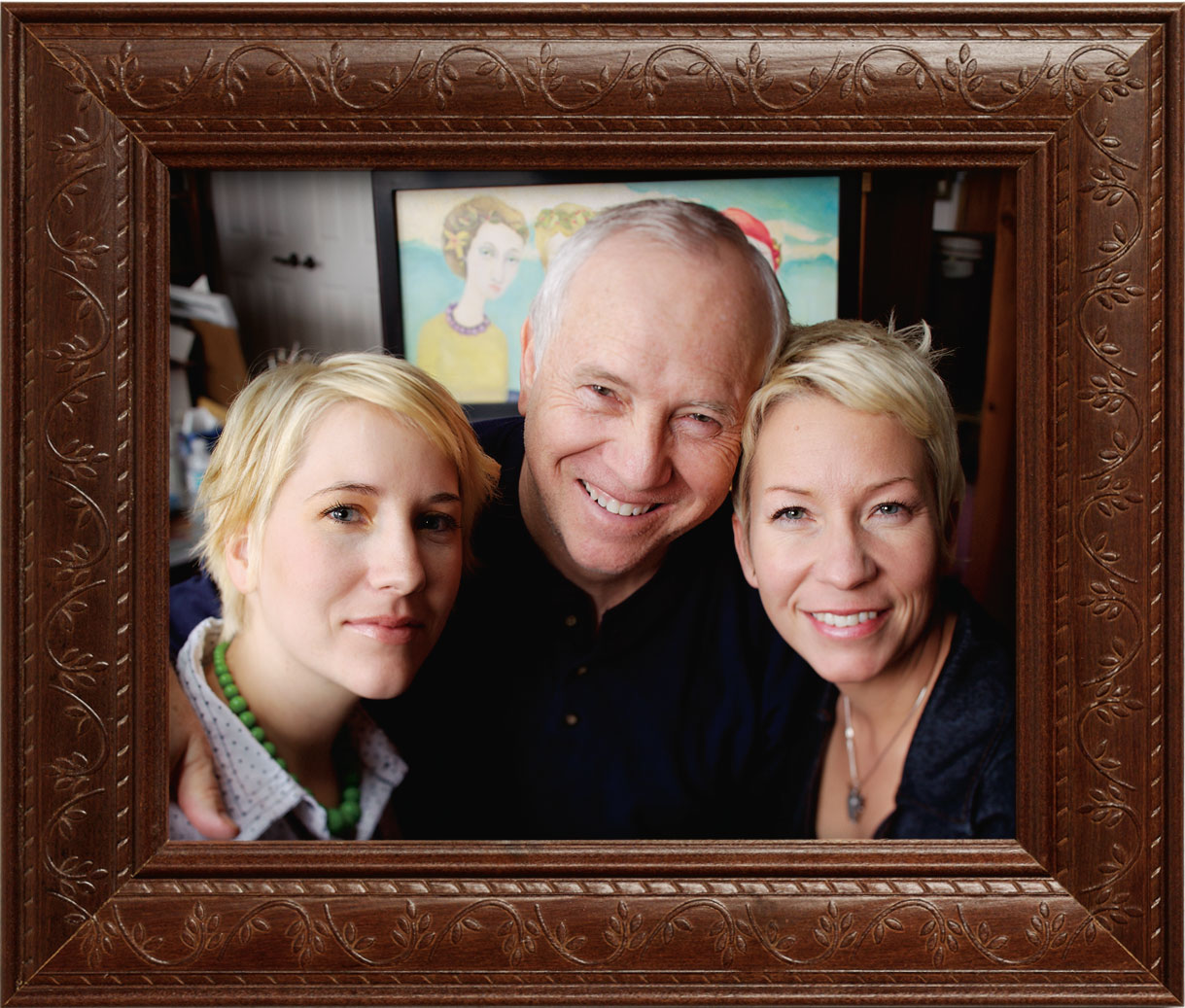

Although Christensen didn’t plan for his daughters to follow his footsteps, he is a proud parent and gladly describes how their artistic paths differ from his own. “I see many children of artists who become clones of their parents,” Christensen says, “but my daughters have found their own way. Cassie does portraits of women. She is a little more contemporary than Emily, and her art is insightful and direct. Emily has a nice nostalgia about her work and creates soft, surreal paintings that deal with her children. Her art reflects more attention to detail. I see completely different styles, which makes me happy.”

But their art is not without similarities, Barney says. “Our art is full of imagery. For me, that is the most important part. Usually the concept is more important than the painting.”

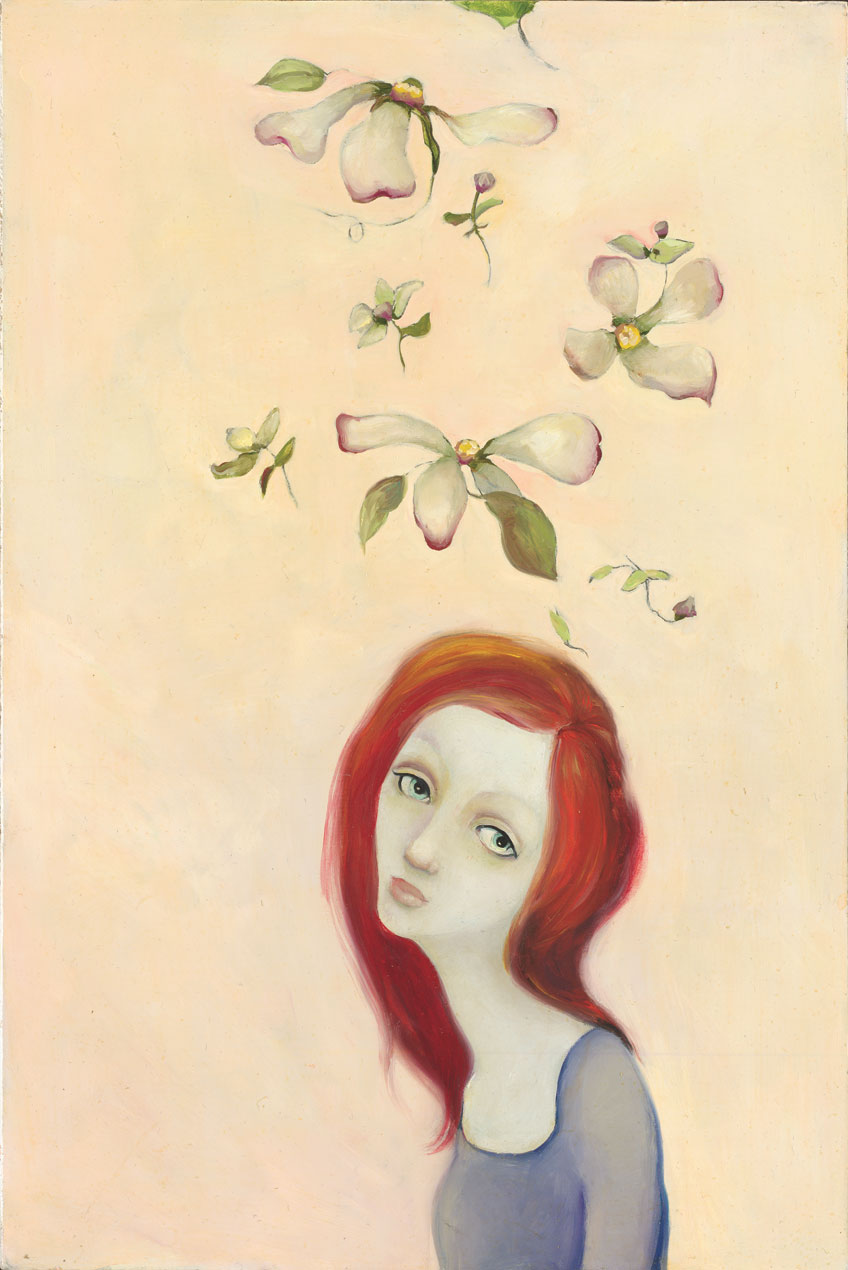

For Barney, art is a personal catharsis in which the paintings bring to light the story of her life and help her comprehend the world around her. “I paint women,” she says, “because that is what I recognize and what I know.” In her work she explores the intricate complexities of human emotions, largely through women who are not so much beautiful as vulnerable. There is an ambiguity in her slender, soulful creatures that invites personal interpretation.

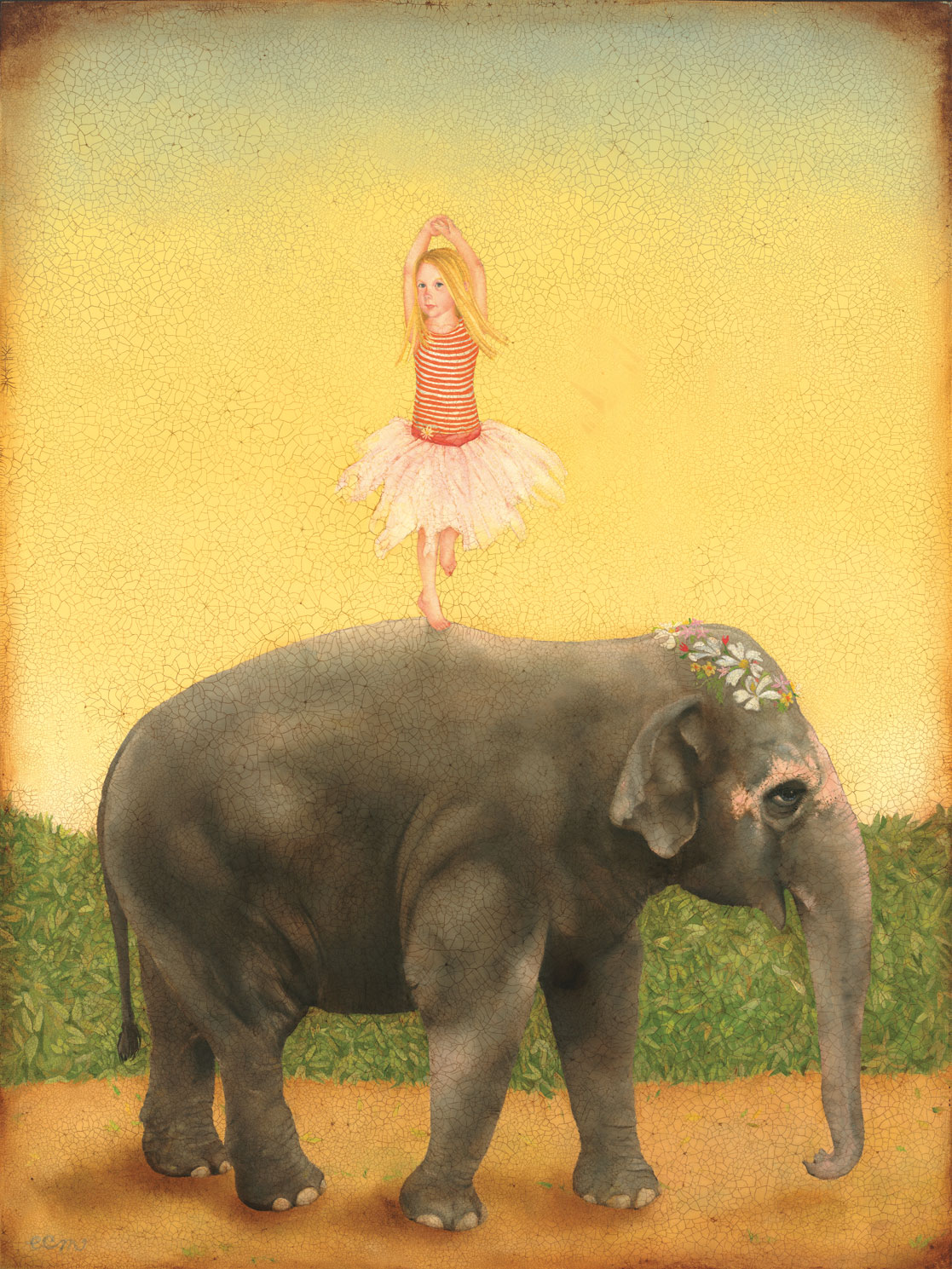

McPhie describes herself as being in a land somewhere between Barney and her father. Her art reflects her life, and if one knew nothing about her, it would be easy to infer that she is a mother simply by looking at her art. By her own description, she sets out to imitate the purity of a child’s imagination, where there is a fuzzy line between what is real and what is make-believe. She does this with classic poses and antique finishes that still exude a contemporary flair. Many of her works look as if they could be captured and treasured inside of a locket. “Much of what I paint deals with my life around my daughters. I hope they trigger tender emotions of motherhood. Sometimes I delve into the toil and the labor of children, but I always deal with finding joy.”

Sisters, Mothers, Daughters

Barney is a decade older than McPhie, her youngest sibling, and in some ways is as much a mentor as a sister. For a time Barney taught high school art, and her sister found her way into Barney’s classes for her junior and senior years of high school. Barney encouraged her sister, telling her, “You should be doing this; you have real talent.” Later Barney would introduce her sister’s work to the Terzian Gallery in Park City, Utah, where it was accepted.

The mentoring has continued through long-distance phone calls. “I wanted her advice because I felt I was getting successful, and I didn’t want to be intimidated and get locked into a certain style because it sells,” McPhie says of a recent conversation. “She told me that painting what was true to me is more satisfying and more important than trying to make it well received. She added that we’re fortunate, because as wives and mothers we haven’t had to worry about being commercial.”

Like her sister, McPhie works out of her home studio. And like her sister, she shares her work with her children. “Half my studio is their table with their drawers filled with paper and supplies,” she says. “This keeps them busy while I keep painting.”

As the two mothers extend their art to their daughters, a third generation of artists is emerging. The younger girls explore drawing, sewing, writing, and even creative sculpture. “If you want to make Fiona happy,” says Christensen of one of his granddaughters, “just give her tape and a gigantic role of aluminum foil.”

Perhaps influenced by his daughters, Christensen’s old “unless you are on fire” stance appears to be softening. His studio now includes painting space for a second artist—often a daughter—and there’s a table just waiting for his grandchildren.