Ten Years to the Top

National championships don’t happen every day at BYU, or anywhere else. Nor, for that matter, do they happen overnight. Which is exactly why the crown won by the men’s volleyball team is doubly extraordinary.

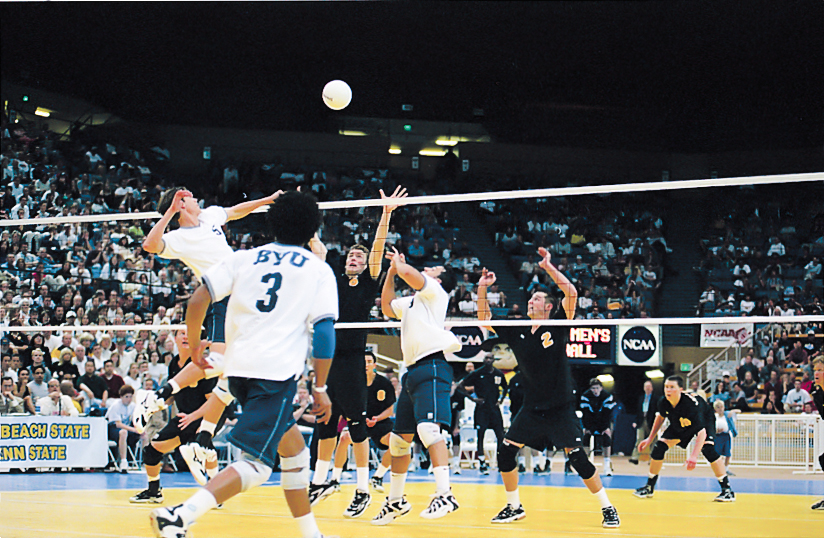

On a balmy May afternoon in Los Angeles, the No. 1-ranked Cougars swept No. 2 Long Beach State in three games to claim their first title in their first-ever appearance in the Final Four. In the process they avenged their only loss of the season and brought home the school’s fifth national championship. (The others are men’s outdoor track and field in 1970, men’s golf in 1981, football in 1984, and women’s cross country in 1997.)

What’s more, though the Long Beach campus is not far from the site of the Final Four, the Cougars had a decided home-court crowd advantage, as the majority of the 8,000 in attendance wore blue and screamed for BYU. When the Cougars’ Ossie Antonetti scored the match-clincher with a cross-court kill, he touched off a delirious celebration.

And Y not? BYU began the decade at rock-bottom as a newly NCAA-sanctioned program. By the end of the decade, the Cougars were on top of the men’s volleyball world. It marked only the second time in 30 years of play that a school outside the volleyball-crazed state of California had claimed the national championship.

“When you think of big-time college volleyball, you generally think surf, sand, bronzed bodies, and, yes, California. Then you see BYU, a school, as coach Carl McGown likes to point out, that is best known for its mountains, Mormons, and missionaries.”

Okay, there are only 25-plus men’s volleyball programs in the country. And, yes, BYU’s roster is filled with California natives (though it should be noted that of its six starters, two were from Puerto Rico and another was from Oklahoma). Nevertheless, the Cougars’ ascension stands as a remarkable achievement.

When you think of big-time college volleyball, you generally think surf, sand, bronzed bodies, and, yes, California. Then you see BYU, a school, as coach Carl McGown likes to point out, that is best known for its mountains, Mormons, and missionaries.

So how did land-locked, snow-drifted BYU become the king of NCAA volleyball?

Well, it wasn’t easy. In 1990 McGown was handed the reins of the brand-new BYU volleyball program and was placed in the toughest league in the nation. The Cougars had to compete with the likes of UCLA, Southern Cal, and Pepperdine. Prior to this, volleyball was successful as a club sport at BYU, but moving from club sport to the NCAAs is a jump of Evel Knievel-like proportions.

McGown knew that when he took the job. And the first couple of seasons weren’t pretty. “We got our brains beat in,” he says. More specifically, BYU posted a 7–48 record after two years and won only two league games during that span.

“It was brutal,” recalls current assistant coach Hugh McCutcheon, who was a part of the early Cougar teams. “You had to ask yourself if you wanted to stick around.”

McGown and others not only stuck around, they made tremendous recruiting inroads in the rich talent pool in California and also discovered players around the world who wanted to attend BYU. When Rondo Fehlberg became athletic director in 1995, he met with McGown to assess the program. “McGown told me, ‘Give me the resources, and I will deliver you a championship,’” Fehlberg says. “He said he couldn’t guarantee it but that we had a good chance. We got him the resources and he’s done it.” Those resources included granting McGown full-time status as a coach and allowing him to hire two full-time assistants.

Gradually, the Cougars became a perennial power. In 1997 they spent several weeks ranked No. 1 in the country, and they finished in the top 10 in 1994, 1995, 1997, and 1998. The last three seasons they have gone 66–13. And in 1999 that series of fine seasons culminated in a championship for the 61-year-old coach and his team.

Important in the Cougars’ rise were the tremendous contributions of McGown’s two senior All-Americans, Antonetti and Ryan Millar. Antonetti was recruited from San Juan, Puerto Rico, by former Penn State coach Tom Peterson. When Peterson took an assistant coaching job at BYU, Antonetti followed him. He arrived unfamiliar with the LDS Church and unaccustomed to Provo’s chilly winter weather. But he thrived in the BYU environment and on the court. At 6-foot-1, Antonetti played a position typically occupied by players several inches taller, but he compensated for this disadvantage with his reported 40-inch vertical leap.

“McGown, wanting more unity, declared the team a peroxide-free zone.”

Fan-favorite Antonetti was also instrumental in attracting fellow Puerto Rican Hector Lebron to BYU. The pair were childhood friends. When Lebron showed up on campus, McGown did not even know who he was. But a couple of years and more than 3,000 career assists later, Lebron became a second-team All-American.

Millar, a high school star from Lancaster, Calif., was recruited by all the top programs, including UCLA and Pepperdine. He chose BYU partly because he is LDS and partly because he enjoyed the challenge of helping a program on its way up.

Until his senior season, Millar had beach-blond hair. Then McGown, wanting more unity, declared the team a peroxide-free zone. The 6-foot-8 Millar, who holds the career records at BYU in kills and blocks, obediently replaced his surfer’s ’do with a standard, BYU-issue haircut and his natural brown locks. And then, as team captain, he helped the Cougars claim their championship. Who says blonds have more fun?

All told, BYU won 30 games, defeated then-No. 2 UCLA during the regular season (and beat the Bruins 15–0 in one game–a rare feat), and won their first-ever Mountain Pacific Sports Federation title.

In Provo the Cougars became the hottest ticket on campus, drawing record crowds. They set an NCAA attendance mark in February when more than 14,000 fans showed up at the Marriott Center for a match against Hawaii. Typically, BYU plays in the friendly confines of the Smith Fieldhouse, which for visiting teams has become one of the most feared lairs in college volleyball. Coeds screamed and swooned for the players like they were rock stars, and some male students were known to paint their faces and chests in support of their team. The decibels inside the Fieldhouse reached eardrum-shattering levels. Another large, boisterous contingent followed BYU to UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion for the Final Four. Based on sheer volume, a listener might have thought the match was being played at the Fieldhouse.

When the championship match was over and the Cougars had humbled a brash, young Long Beach State squad by the score of 15–9, 15–7, 15–10, McGown remained relatively calm, at least publicly. BYU’s meteoric climb to the top was complete, and he was enjoying the view. “There’s a lot of satisfaction,” McGown says. “We’re not a doormat anymore.”

While McGown, who was later named national coach of the year, was finally able to relax a bit and flash a smile, Cougar players were less subdued. Antonetti, for instance, grabbed the championship trophy before the official presentation, raised it above his head, and proudly displayed it to the jubilant crowd.

“Nobody can take that trophy away from me,” he said later. “I wanted to end my career winning and I did.”

“We’re not a doormat anymore.” —Carl McGown

And at BYU, a national championship doesn’t happen every day. As McGown would attest, it doesn’t happen overnight, either.

Considering how things started, even he probably wouldn’t have thought it would take only 10 years.