By Val Hale

When President Merrill J. Bateman introduced Steve Cleveland as the new Brigham Young University basketball coach at the conclusion of the March 11 devotional, an audible wave of surprise swept through the Marriott Center. Fifteen minutes later, Athletic Director Rondo Fehlberg stood before cameras and microphones at a press conference and stunned media and basketball fans throughout the state with his announcement that Cleveland would become the Cougars’ new coach.

Amid all the surprise and the “Who’s he?” questions, the person most shocked by the announcement may have been the new coach himself. Cleveland knew he was a serious candidate for the job, but he also knew from personal experience that he shouldn’t let his hopes of winning the position rise too high.

Three years previously, he had interviewed with Roger Reid for the assistant coach position left vacant by Charles Bradley’s departure. Reid had invited Cleveland to visit Provo and meet with key people associated with the basketball program. After nearly a week on campus, shaking hands and trying to make a favorable impression on those he met, he returned to Fresno feeling good about the interview process and confident about his chances of landing a job at BYU, a school he had never attended but had followed with interest for most of his life.

When the call finally came, it was not what he had expected or hoped. Reid explained that he would be hiring Lynn Archibald as his new assistant.

“I was devastated and very disappointed,” Cleveland says. “I really thought that the timing was right and that I had something I could offer BYU and Roger Reid. But after a lot of soul-searching thought and prayer, a peace came over me that Roger had made the right decision in hiring Lynn.”

Memories of that profound disappointment, combined with the realization that he lacked significant connections at BYU, kept Cleveland’s expectations and emotions in check as he observed and participated in the BYU search process during February and March.

“As I got involved in the process, I had mixed emotions,” he recalls now. “I am not an alumnus of BYU. I have many friends in Utah, and I know many of the coaches in the state. But I really did not have any close associations with those in the administration at BYU. Pursuing and landing head coaching jobs these days requires having close friendships with athletic directors, presidents, and faculty members. I did not have those contacts.”

What Cleveland failed to account for is that several of the key people on the search committee were familiar with him. A year previously, Roger Reid had encouraged Fehlberg to meet with Cleveland while the Cougars were in Fresno to play the Fresno State Bulldogs. Fehlberg was impressed with what he saw. In addition, Lynn Archibald, who assumed the position of Director of Basketball Operations in December, had lived in Fresno and knew Steve and his family well.

Not surprisingly, as the search committee spoke with coaches and knowledgeable basketball people, Cleveland’s name kept surfacing.

Meanwhile, Cleveland debated whether to apply for the job and eventually called his friend Roger Reid to seek advice.

“Roger indicated to me that the job was no longer his and that I needed to be involved in the process,” Cleveland recalls. “My first reaction was that I wasn’t going to get involved. I was going to let time go by and see what happened.”

Not long after that telephone conversation, however, the committee contacted Steve and asked him to apply for the position. He thought about their invitation and finally submitted his application.

The committee explained to Cleveland that the search process would be done in strict confidence. Media pressure to uncover the list of top candidates was great. Reporters daily tossed out names of people they believed were or should be candidates. Rumors about the candidates and supposed frontrunners swirled daily in the newspapers, and debates raged on the radio sports talk shows. Each name that surfaced was thoroughly critiqued, placed under the media microscope, and evaluated ad nauseum by the press. Throughout the entire process, Cleveland’s name remained out of the limelight, surfacing only occasionally in the “also being considered” category.

During his seven years at Fresno Community College, Steve Cleveland turned his team into one of the top community college programs in California.

The lack of publicity about Cleveland’s candidacy for the position was both a blessing and a source of concern for the Fresno City College coach.

“Confidentiality was really important to me through this process because I didn’t want anything to distract from the season at Fresno and the young men that I was coaching there,” he says. “When the media would come out with a ‘top 10’ or ‘top 5’ list, my friends from Utah would send me the articles. I always laughed to myself because I knew that I was involved in the process, but nobody else did.”

But Cleveland also realized that the lack of media attention might hurt him in the long run because of the weight that public opinion often carries in such decisions. “I think the only insecurity I had was that it would be hard for BYU to hire Steve Cleveland because he’s not a household name in Utah; he’s not one who is recognized in the state,” he says. “I am confident about my coaching abilities, my recruiting abilities, and my ability to get the job done. But I also recognize that this is a business and that this institution has a huge alumni association and great booster groups, and I think it may have been easier for the administration to hire someone else.”

While Cleveland waited and worried in Fresno, hidden from the glaring media spotlight, the search committee was busily–yet quietly–at work in Provo. The committee consisted mainly of a core group of individuals which included Advancement Vice President R.J. Snow, Athletic Director Fehlberg, Associate Athletic Director Pete Witbeck, and Archibald. Others were invited to assist with the process, as needed.

The list of candidates grew rapidly. From the moment Fehlberg made the announcement that a national search would take place, applications began piling up on his desk.

“There were many applicants, but we considered about two dozen to be viable,” Fehlberg says. “Those interested in the job ranged across the spectrum from the professional ranks through all divisions of the NCAA, and even some highly successful high school coaches.”

After reviewing the applications, the committee culled the list down to about 12 candidates, whose credentials and background were examined in depth. That list was then cut in half to create a short list, and the committee sought permission to interview the finalists.

One by one the finalists met face-to-face with the committee or, if such a meeting was not possible, interviewed over the telephone. Cleveland flew to Provo for his interview and left feeling that he had scored valuable points with the committee.

“Areas where I have concentrated my personal development efforts include my ability to communicate with people,” he says. “I think the committee members could sense and feel that. I think they knew I had a vision and a plan. I came prepared. I was sensitive to the things they were sensitive to. Even though I lived 900 miles away, my perception was that a healing needed to take place.”

Snow was the committee member who knew the least about Cleveland. He and his wife, Marilyn, flew to Fresno in late February to observe Cleveland in action at a game. They visited with Steve and his wife, Kip, in their home, met Casey (19), Skyler (16), and Katie (6), and then drove to a nearby junior college, where Cleveland’s Fresno City College team was playing. FCC won that night by 20 points.

Once the interviews were completed and all the information gathered, the committee began evaluating the candidates one last time. Each candidate had specific strengths that were obvious to committee members. Fehlberg admits the decision was a difficult one.

“The committee was satisfied that each of the candidates on our short list could have been successful at BYU,” Fehlberg says. “But, in the end, we felt that Coach Cleveland was the best for the long-term objectives of our program. We just felt better about Steve. There wasn’t anything we could point to where we could say, ‘Aha, here’s the thing.’ We were looking at a group of very good candidates, but we had to pick one. We felt good with Steve.”

The committee passed its recommendations on to President Bateman for confirmation, and word came back on Monday, March 10, that Cleveland would be BYU’s next coach.

The entire search process was conducted under strict confidentiality for the benefit of the candidates and BYU. Only a couple of leaks occurred, and those came from potential candidates or their superiors, who chose to make the news of their candidacy public. The committee’s ultimate challenge was to notify the Clevelands of their selection, get them to Provo, and call a press conference without having the media catch wind of the decision.

R.J. Snow called the Clevelands on Monday, March 10, and shared the good news with them. He asked them to catch a flight to Salt Lake City the next morning so they could be introduced at the devotional and at the press conference. Steve requested permission to tell his FCC players, which he did that night in a special team meeting. He also shared the news with his parents and other close family and friends in Fresno.

Members of the search committee sat silently while a local paper carried a large headline Monday evening mentioning the name of another candidate as frontrunner for the job. A Tuesday morning paper likewise ran a story saying it would likely be several weeks before BYU named its new coach and didn’t mention Cleveland’s name.

The only flaw in the process occurred quite by chance. Bill Marcroft, radio play-by-play man for the University of Utah, happened to be on the same flight as the Clevelands from Fresno to Salt Lake City. He overheard some conversations, saw Steve, and began to put things together in his head. By the time the plane landed in Salt Lake City, he had figured out what was happening. He sprinted to the phone and called a radio station, which began broadcasting the news that Steve Cleveland would be named the new BYU head coach.

Meanwhile, the press conference was set for noon. But before the media met the Clevelands, President Bateman used the devotional setting to introduce Steve to the campus community, setting off the wave of surprise that sent ripples all across the country. He asked, with a smile, that the 17,000 people present “please keep this matter confidential for 15 minutes, until it can be given to the media at a noon press conference at the stadium.”

It didn’t take long for BYU fans to understand why Cleveland had been selected for the job. Though they didn’t know him, they listened on radios and watched on TV as he deftly responded to questions from the media. He answered the questions with honesty, candor, and sincerity. Even some of the most cynical press representatives went away impressed by his performance.

He had aced the first test.

Utah’s newest celebrity returned to Fresno, where his number-one-ranked team was preparing to play in the California junior college championships. It was a team many considered to be possibly his best ever at the college. Cleveland worked hard to make sure his new appointment wasn’t a distraction for the players. They won their first game but lost in the semifinals to Los Angeles City College, finishing the season with a 31-4 record.

The announcement of Cleveland’s hiring was received with mixed emotions in Fresno. As a very successful high school and junior college coach there, Steve had made a positive impact in the community. The headline on the front page of the March 12 Fresno Bee shouted: “BYU picks Fresno’s Cleveland as basketball coach.” Inside, stories lauded Cleveland for his past accomplishments and BYU for selecting such an outstanding person. At the same time, most local people were disappointed to be losing their great coach.

Bee columnist Bill McEwen wrote: “His hiring was so shocking that folks who live and die with Brigham Young basketball are bound to get the wrong impression. They’re going to take one look at Steve Cleveland and figure that the school . . . was determined to hire the last real Boy Scout.

“There’s something to that because Cleveland, 45, is a nice guy. During all his years on the Fresno basketball scene, he has held himself to the highest standards on and off the court. He rarely has a cross word for anybody.”

McEwen then went on to say, though, that “Those boyish good looks and respectful manners hide a competitive streak that is wide and deep and never satisfied.”

The Fresno media were especially complimentary about Cleveland’s influence on the young men in his program. Most of his players were inner-city kids with troubled pasts or an aversion to discipline. Steve made sure that each of those young men graduated from FCC. Many went on to play Division I basketball. Several of his former high school or junior college players stepped forward after the announcement to describe Cleveland as “a player’s coach.”

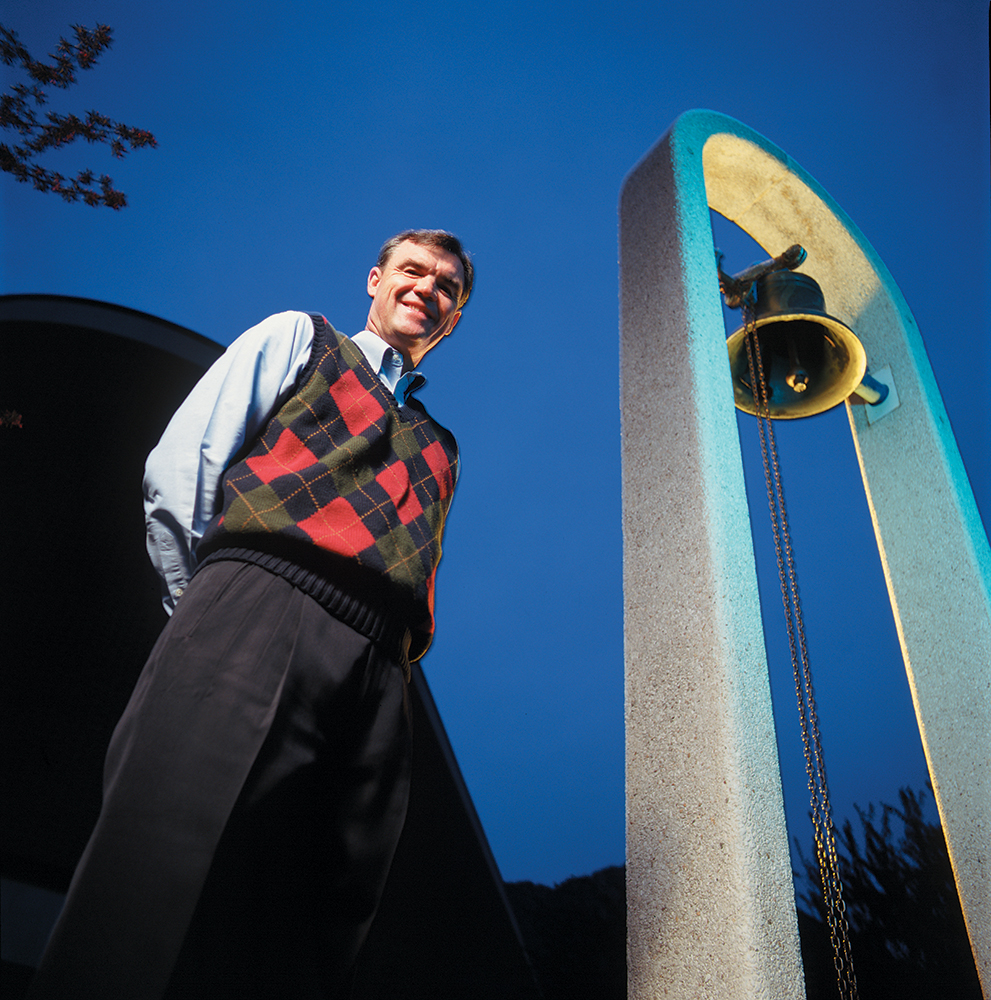

Steve Cleveland meets with the media at the March 11 announcement of his appointment as BYU’s head basketball coach. Although few in the media knew much about Cleveland – and none had named him as a top candidate for the job – he has since scored high marks with both sportswriters and fans.

“The last three years at the community college have been the best three coaching years of my life,” Steve says. “We’ve made more progress, had more success, and touched more lives. A lot of great things have happened. I have predominantly been working with inner-city kids, African-American young men, and that’s been a great experience in my life.”

He left no doubt of his philosophy about his players when he spoke to the Utah media. “You can be critical of the coach as much as you like, and you can second-guess me,” he said. “But let’s not hurt the student athletes. Let’s not hurt these young men who’ve given everything that they’ve got.”

By recruiting good athletes and coaching them in fundamentals, Cleveland’s FCC teams developed a reputation for tough defense and rapid-paced offense.

“I have been totally committed to pressure defense–pressuring the ball, creating offense through defense,” he says. “I have a philosophy that defense and rebounding win basketball games, especially on the road. In terms of offensive philosophies, we’re going to push the ball. The better defense we play, the more opportunity we’ll have to push the ball and score in transition, which is something the fans enjoy.”

Cleveland realizes that his first big task is to recruit athletes capable of playing his style of ball. He is committed to recruit the best athletes he can find, regardless of race, religion, or nationality. He also wants to work with prospective missionaries to try to better manage their comings and goings so the program is not caught with too many freshmen seeing significant action, as was the case last season.

Counseling prospective missionaries is something Cleveland can do from personal experience. He served an LDS mission to England from 1971-73. As surprising as it may seem, Cleveland is the first head basketball or football coach at BYU to have served a mission. He knows what it means to spend two years knocking on doors and bearing testimony. He understands the challenges and the growth that come from missionary service.

Another of Cleveland’s chief objectives is to begin the healing process with BYU fans.

“One of my first and foremost responsibilities, along with recruiting and organizing a program, is that we need to work to bring the community together. We need to bring alumni together. We need to bring all these constituents together and let them know that, together, we can successfully accomplish the things that we want to accomplish. That’s been my vision for the program. It’s a partnership, and an immediate healing needs to take place.”

One of Cleveland’s first tasks in forming that partnership was finding assistant coaches who shared his vision and who would be active in the community and on the recruiting trail preaching BYU basketball. He considered many qualified candidates and eventually decided on David Rose, the head coach at Dixie College in St. George, and Nathan Call, a former All-WAC BYU player who had been an assistant coach at Utah Valley State College for three years.

Rose played basketball at Dixie and then transferred to the University of Houston, where he was co-captain on the famous Phi Slamma Jamma team in 1982, which was ranked number one in the country. He compiled a 167-57 record in seven years as Dixie’s head coach. Six of those seven years, his teams finished the season nationally ranked in the NJCAA.

Call was a popular player for the Cougars in the late 1980s and early ’90s. He was known as a steady, intelligent player and a great floor leader. Cleveland is counting on him to foster relationships with former players and alumni in an effort to mend some of the fences and soothe old wounds.

Cleveland hopes his new staff will bring a new look and attitude to BYU basketball, and that their approach will rekindle enthusiasm among players and fans. He points to his people skills as one of his strengths that will help in recruiting players and spectators.

“I have a great respect for people, and I treat them the way they should be treated,” he says. “I’ve tried not to be a judgmental person. I feel like I need to have an open mind and an open heart toward all people.

“I’m not one who really takes myself too seriously. I feel like the Lord has blessed me; he’s guided my life. I’ve made my share of mistakes, so I think it’s important that I approach this job in a way that I can learn from the traditions of the past. There’s a great deal I don’t know that I have to learn.”

In his first few days on the job in Provo, Cleveland received a heavy dose of Division I reality. As a junior college coach, he was required to handle all aspects of the basketball program, from sweeping the floor before practice to driving the team bus. There was nothing he didn’t do. At the Division I level, however, he quickly learned that there is always paperwork waiting to be done, bureaucracy needing to be tackled, and phone calls needing to be returned, not to mention the development of a new network of contacts and mastery of the NCAA rules. But at least there is a staff at BYU to help out with the sweeping and driving chores.

His first task was to study the inch-and-a-half-thick NCAA manual, and its modern-day Law of Moses regulations. Then he had to pass a test that covered those rules. Finally, after proving that he knew it’s against the rules to do things like drive an athlete across town in his car, Coach Cleveland was free to recruit and do those things that he had done so well as a coach in junior college and high school.

It was only a matter of days before Cleveland was running around the country trying to sell BYU to recruits, find assistant coaches, and make contacts in the coaching fraternity. While he flew from airport to airport, his wife, Kip, and their three children, Casey, Skyler, and Katie, remained in Fresno to finish school and tie together loose ends. There was little time to do things like put the home up for sale in Fresno and look for a new home in Provo. What made it especially hard on Steve was being away from his oldest son, Casey, who had played basketball at Fresno City College and is preparing to leave on a mission this summer.

Transplanting the family to Provo from Fresno will be difficult for the Clevelands. Their roots are firmly implanted in the rich San Joaquin Valley soil. Steve attended high school in Fresno and later starred as co-captain and MVP at Fresno City College. He then transferred to Cal-Irvine, where he earned All-West Coast honors and was named the team’s MVP in 1976.

In 1979, he started up a basketball program at Clovis West High in Fresno, a new school just opening its doors. In 10 years there, he compiled a record of 177-70. He took the team to the state playoffs seven times and won two division championships. He then became an assistant coach for a year at Fresno City College before the administration asked him to assume control of the basketball program.

In seven years, he built the program into what many considered the top junior college program in California. He was enjoying the fruits of his labors when news of Roger Reid’s dismissal reached him. For the first time, the thought crossed his mind that an opportunity might present itself at BYU.

“If you had asked me a year ago if Steve Cleveland was going to be the head basketball coach at BYU, I would have told you it was impossible because I fully expected Roger to be here for 10 or 15 more years,” he says. “I just assumed that things would remain status quo. I will say, though, that throughout my life, I’ve had very strong impressions that I would someday live in Utah.”

The Cleveland Era is now officially underway at BYU, and the early report card from the athletic director and the fans has been favorable. “It has been gratifying in the weeks since our announcement to have our feelings confirmed as we have watched Coach Cleveland with the press, the public, his players, and our recruits,” Fehlberg says.

Word about Cleveland’s past coaching success has slowly spread throughout Utah. People are impressed by the way he has tackled the job and gone about rebuilding the program. He hasn’t won a game yet, but it’s safe to assume that people won’t feel near the surprise if he becomes successful at BYU as they felt when President Bateman first announced his name on March 11.

Vale Hale is the assistant athletic director for media relations at BYU.