By Elyssa Renee Madsen

At a forum assembly on Feb. 23, BYU students heard Linda Brown Thompson and Cheryl Brown Henderson unfold the history of Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark court case that ended public-school segregation. Thompson and Henderson are daughters of the late Reverend Oliver Leon Brown, one of the 13 parents who in 1950–under the direction of the NAACP–filed suit against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kan., for prohibiting black children from attending white schools.

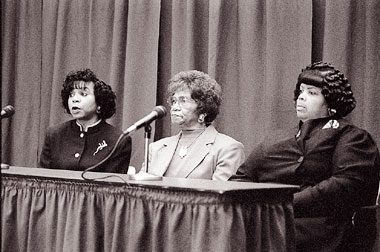

They lived civil rights history: Cheryl Brown Henderson (left), Linda Brown Thompson (right), and their mother, Leola Brown Montgomery, told BYU students the story of Brown v. Board of Education, the case that ended public school segregation.

Thompson described the conditions that led to the suit: As a child she had to walk seven blocks to reach the bus for an all-black elementary school, even though there was a white elementary school minutes from her home. Her walk included a trek across a railroad yard and through busy intersections–in winter her tears often froze before she reached home.

Conditions like these angered black parents, and by 1950 the NAACP had recruited 13 families to challenge public-school segregation in Kansas. That fall Thompson made another walk–this time with her father as he gathered evidence of Topeka’s segregation policy. She recalled, “A mild man took his plump seven-year-old daughter by the hand and walked to the all-white school and tried without success to enroll his daughter.”

For the Browns and 12 other families, that morning was the prelude to a case that would last four years and be argued all the way to the Supreme Court, where it would be combined with similar segregation cases from four other states.

In May 1954 the Supreme Court unanimously declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional, striking down the earlier notion that public schools could be separate as long as they were equal. Earl Warren, then Chief Justice, said, “In the field of public education, ‘separate but equal’ has no place.”

Henderson told students one of the most important outcomes of the case was that it “made clear that the federal government did, in fact, have enforcement authority with respect to the Constitution, over each and every citizen.” She said the decision clarified that the Constitution protects U.S. citizens from arbitrary restrictions placed on their rights by state and local governments.

Henderson pointed out that many people contributed to the victory. “It wasn’t as simple as an individual taking a stand,” she said. “It was organized, developed, and strategized by the NAACP, which is important because it shows the power in numbers.”

The sisters urged students to maintain the dedication to civil rights that existed in the 1950s and 1960s. “Young people today haven’t had to experience the things we and other people went through before integration,” Thompson said. “You can’t be complacent because things are changing daily–you have to be fighting on the forefront.”

Fighting their own battles for social justice, Thompson and Henderson work for the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence, and Research in Topeka, Kan. Established as a tribute to the plaintiffs and attorneys in the Brown case, the foundation offers scholarships to African Americans pursuing careers in education, and it is helping to build a library for inner-city children in Topeka. After the forum, the BYU chapter of the National Association of Social Workers presented Thompson and Henderson with more than 500 books collected for the library.

Both sisters emphasized they want students to understand the history behind Brown v. Board of Education so they will feel empowered to fight for social change.

“The change we enjoy today came about because of young people,” said Henderson, noting that many of the attorneys for the Brown case were fresh out of law school. “The reason this is important for today’s youth to know is it says that the power doesn’t have to be silent within them. Generally speaking, they are the ones who will make the kind of difference that needs to be made.”