Two BYU grads have developed a novel therapeutic that attacks 90 percent of cancers.

There are more than 200 types of cancer, each a distinct medical challenge to address. Finding a treatment for even one cancer is a feat. But a universal drug that targets almost all of them? That is the goal of two BYU alumni at Purdue University.

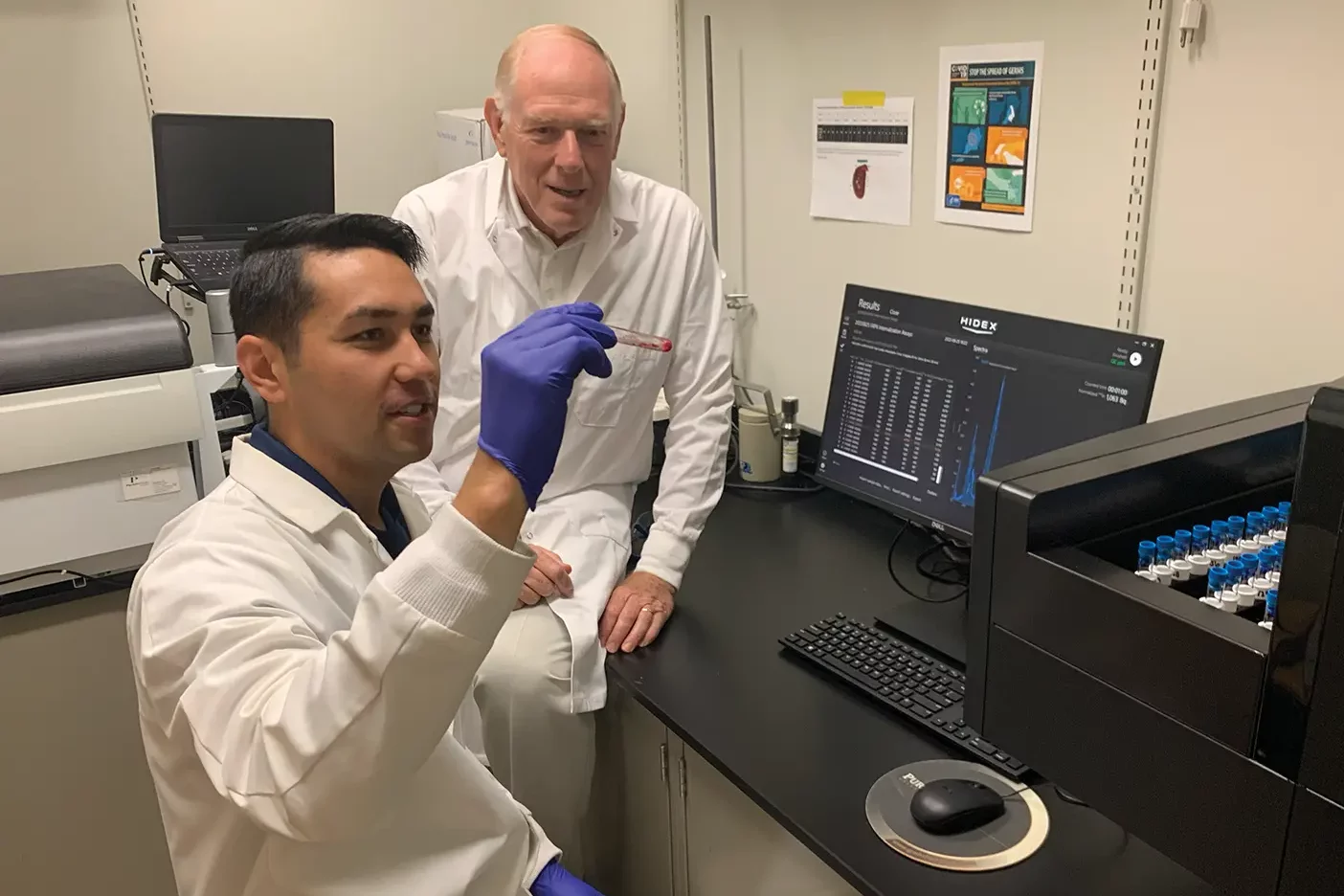

After getting his start in chemistry at BYU and completing a PhD at the University of California, San Diego, Philip S. Low (BS ’71) has studied and developed pharmaceuticals at Purdue for more than four decades, accumulating patents and revolutionizing cancer therapies. He has already created three FDA-approved tumor-targeting drugs that treat patients today.

But now Low has set his sights on a nearly universal cancer treatment. And to achieve that goal, he turned to a fellow alum for research assistance.

When he came to BYU, Spencer D. Lindeman (BS ’14) intended to study engineering, but he felt unsettled about his major. Pondering and praying for months, he turned to his patriarchal blessing. “A line . . . stood out to me,” Lindeman says. “It said that I would work to uncover the puzzles of life.” He felt impressed to major in biochemistry.

Later, as a senior seeking to know his next step, he attended a campus presentation by Low. “It was the most interesting seminar I’ve ever been to,” Lindeman says. “In that moment, I felt the Spirit tell me, ‘You need to go work for him.’” Heeding the prompting, Lindeman applied to Purdue’s PhD program and was hired to work at Low’s lab.

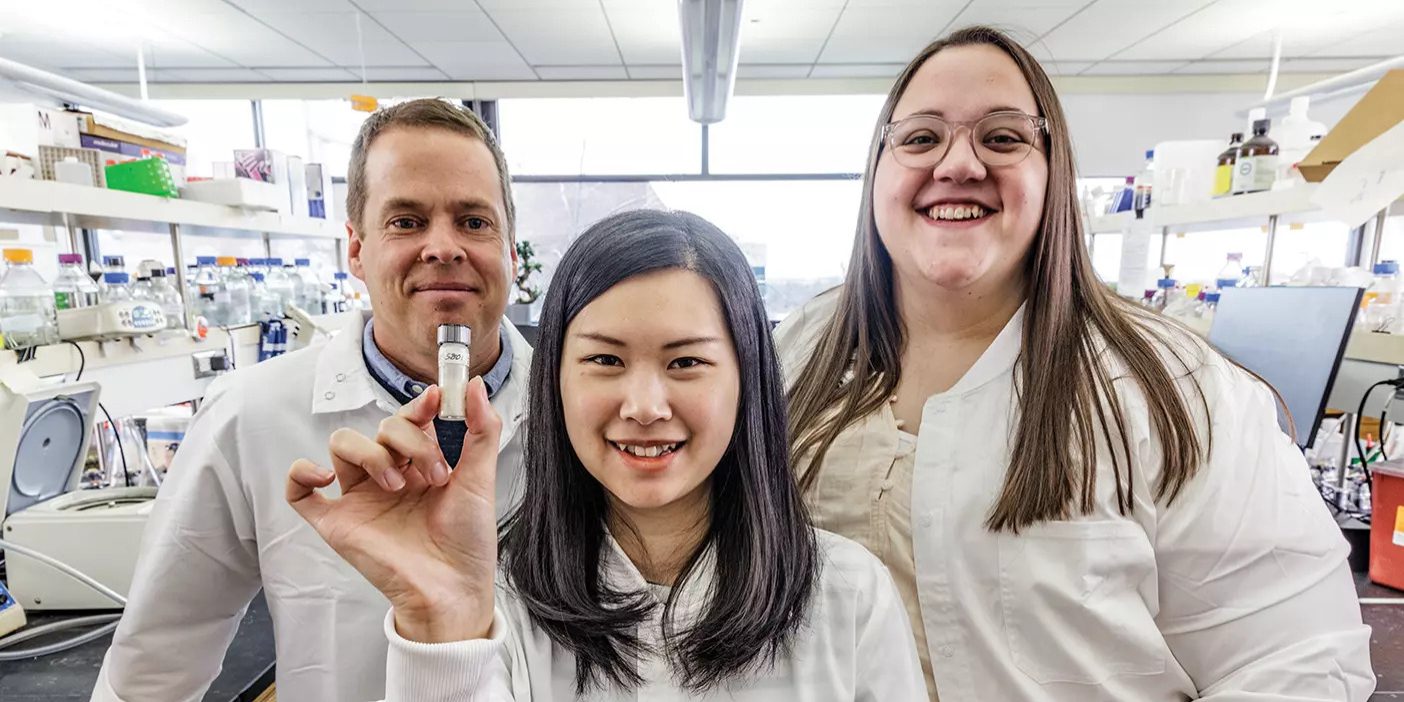

Low set Lindeman to work on a new project to target a certain protein that is present in most human cancers. After working together for several years, they developed a molecule that takes advantage of cancer-associated fibroblasts, healthy cells that cancers frequently hijack to grow malignant tumors. These fibroblasts produce a unique protein found in 90 percent of cancers—the fibroblast activation protein (FAP).

“We have to appreciate just how rare that is in cancer,” Lindeman says, “to find a protein that is so consistently expressed from cancer type to cancer type. It’s remarkable.”

After hundreds of hours and many sleepless nights, Lindeman and Low created a drug that enters the bloodstream, concentrates in the solid tumor by attaching only to the FAP protein, and emits radioactive particles that destroy the cancer’s DNA before leaving the body.

“We had to devise a way to prolong the circulation and keep [the drug] from being cleared out too quickly,” Lindeman says. But to avoid damage to healthy tissues, they couldn’t keep the radioactivity in the patient for long. Currently, they are tweaking the structural aspects of the molecule to maximize tumor damage and minimize damage to healthy tissues.

The team tested the molecule’s efficacy in mice with colon, brain, breast, and cervical cancer. “Most papers, when they do these FAP-targeted radiotherapy studies, they only test one type of cancer. We tested four,” Lindeman says.

The test results were promising. For colon cancer, mice that received the drug had a 100 percent survival rate (compared to just 20 percent in the control group). And there was a significant improvement for the other cancers as well, despite the unusually challenging tumor models used in the experiments.

Lindeman and Low published their studies in The Journal of Nuclear Medicine and hope to move to human clinical trials. The entire process can take years and millions of dollars before the FDA approves a drug. The two are using this time to perfect the drug.

Low says it’s rewarding to develop treatments that save lives. “I feel very fortunate to have had the opportunity to work on projects that really matter, that can change the survival of our fellow man and improve their lives.”