Using rhyme and alliteration, a BYU professor is developing literacy skills in at-risk children.

Barbara Culatta is Dr. Jeckyl and Ms. Hyde in the best possible way.

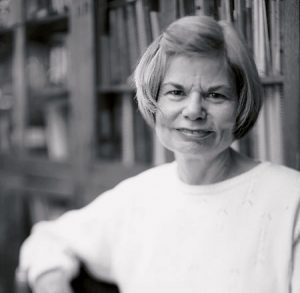

Dr. Culatta sits very still in her office, surrounded by academic books, miscellaneous papers, and children’s toys. She is dignified and articulate, speaking in soft tones and large words.

Ms. Culatta is a fireball, a bundle of energy running around a circle of preschool children gathered for an imaginary train ride. She is enthusiastically shouting, “Rack! Sack! Rhyme!” as she repeatedly shows the children a sack they need to place on the rack so the train can leave the station.

The children can’t get enough of Ms. Culatta, and academia apparently can’t get enough of Dr. Culatta. A professor of audiology and speech-language pathology at BYU, Culatta is on her fourth year of a $450,000 federal grant to study early literacy interventions in at-risk populations. The results so far are promising, showing that early, targeted, and concentrated intervention can help at-risk children reach and maintain grade-level literacy.

“There is often a mismatch between the expectations in the classroom and the literacy experiences these children have had in the past,” Culatta says. “Some children come from environments where there isn’t that literacy expectation or even opportunity because some families are so busy just trying to survive.”

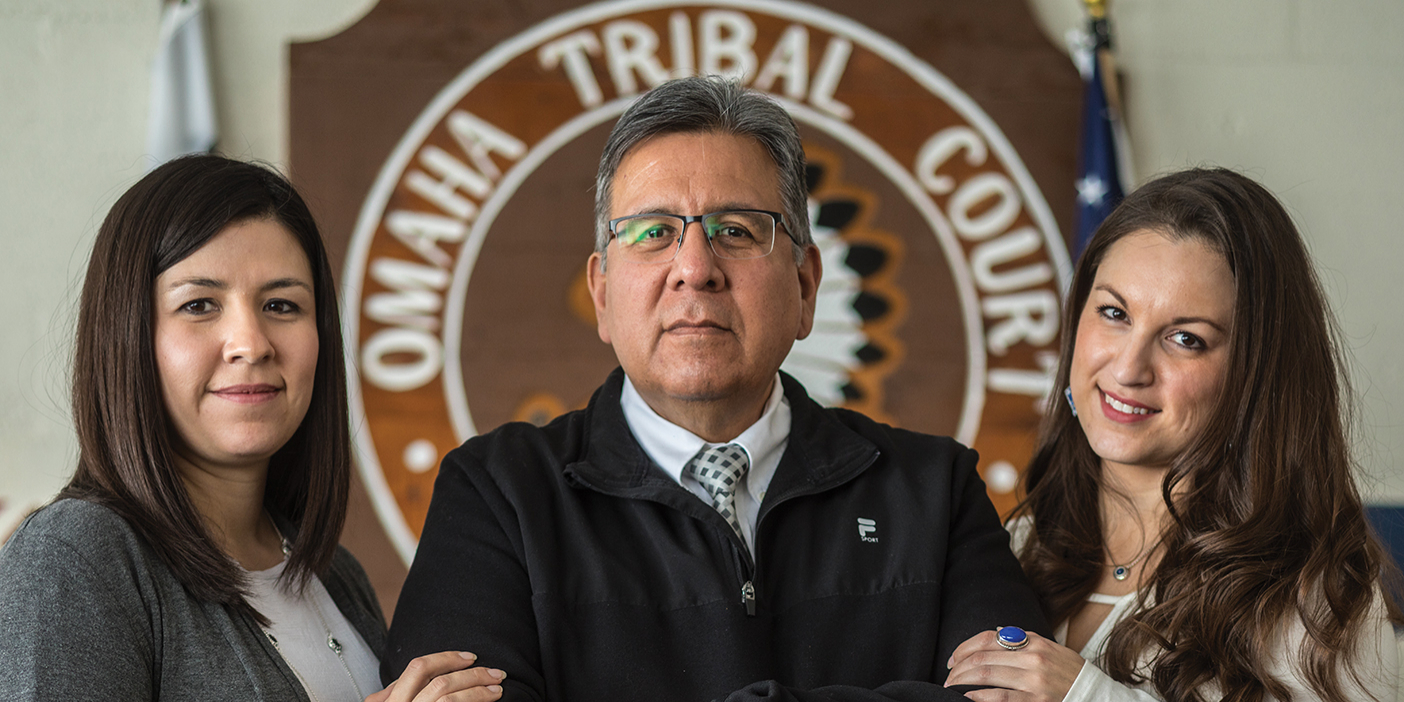

With a $450,000 grant, Barbara Culatta is using rhyme, alliteration, and technology to improve Head Start literacy programs for at-risk children. Photo by Bradley Slade.

Working with preschool children through the Head Start program and with kindergartners in dual- language classrooms, Culatta’s goal is straightforward: to keep children on track before they get off track.

The name of her Head Start research is Project CALL—a “Contextualized Approach to Language and Literacy Instruction.” The method is to focus on the phonological aspect of language and to cultivate the understanding that language is made up of sounds.

“We place heavy emphasis on aural skills because they are so important in learning to read,” Culatta says. “To learn to read you have to realize that words are made up of sounds that can be separated and put back together.”

To help children develop this awareness, Culatta and her student assistants reduce language and literacy to phonological basics such as rhyme and alliteration. “Cat! Hat! Rhyme! Cat! Hat! Rhyme!” is a familiar chant in one of Culatta’s lessons. “We are eliminating all unnecessary language and really just bombarding them with these rhymes, so it becomes very salient,” says Maren Richter Reese, ’01, a graduate student in speech-language pathology who has worked with Culatta for three years.

The bombardment comes through literally hundreds of interactive, hands-on, and fun activities. “The goal is to have some sort of systematic instruction where you ensure that they are learning particular skills,” says Culatta, “but you do it in really fun, motivating ways.”

For instance, the class reads a book about sheep in a jeep; then the children make sheep hats and reenact the story. The instructor takes their photos with a digital camera and together they create their own version of the book in a simple PowerPoint presentation. All the while the instructor reminds them: “Sheep! Jeep! Rhyme!”

In another activity they bake a cake. They make the cake and bake the cake. “Bake, cake!” the instructor impatiently commands the food as the students wait anxiously.

The spoon-full-of-sugar approach seems to work well. The children hardly know what’s hit them. “They really enjoy participating because it’s so much fun,” Reese says. “And at the same time we are indirectly teaching them these skills.”

Janet Crapo, ’02, a graduate student in speech- language pathology who has worked with Culatta for almost two years, remembers a particular success with one Head Start child who spoke very little English. “We did a letter-b alliteration activity outside one day—blowing bubbles, breaking and bursting bubbles, saying bye-bye to big bubbles and baby bubbles,” Crapo recalls. “I remember him standing there repeating, ‘Bubbles, bubbles, bubbles,’ learning the new word. By the end of the year he had made amazing progress with English.”

Despite the reputation Barbara Culatta has earned as a serious researcher, she has no qualms about shedding academic austerity to teach kids using innovative, energetic methods. Photo by Bradley Slade.

While the focus of Project CALL and Culatta’s federal grant has been preschoolers in Head Start classrooms, Culatta has also taken significant interest in children from dual-language backgrounds and has expanded her research interests to include dual-language kindergarten classrooms. Children with diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds often face similar challenges as children from low-income environments—often they are the same children.

“Our overall goals are the same in the sense of making sure that these children are going to be successful at meeting at least grade-level performance by the end of kindergarten,” Culatta says.

Using similar methodologies as in the preschool setting, Culatta and her student assistants reinforce more sophisticated phonological patterns and introduce printed words.

A typical lesson in a kindergarten classroom starts with an activity that helps children focus on words with similar sounds. Then, with the help of the instructor, they write their own simple story about the activity using those words. The instructors take digital photos and compile the newly written stories into an electronic book or a chart story, and then the class reads their story together.

“All of the literature in working with children from culturally diverse and low-income backgrounds talks about how important it is for children to have a voice in their experiences and for instructional activities to relate to their personal experiences so that the activities activate and motivate them,” Culatta points out.

Culatta has also found the classroom context to be a supportive environment for developing social skills, providing important peer support to children who struggle. In one scenario, two Spanish-speaking children were playing with gooey clay the instructor called muck. They had done a rhyming activity with the word muck: “Yuck! You’re stuck in muck!” The instructor asked these two children: “What rhymes with muck?” The little girl understood and responded, “Yuck!” But the other child struggled. Seeing his confusion, the little girl leaned over and whispered, “Stuck.” The little boy shouted with a giggle: “Stuck!”

“Not only do they pick up the rhyme and the skills, there’s an amazing difference in their self-confidence,” notes Reese.

That is an important secondary result when you consider the purpose of the Head Start program. “Our main goal is to develop their social competence and their individual confidence in themselves,” says Patti Peregoy, an instructor in the Mountainland Head Start program, based on the BYU campus.

In her three years of working with Culatta and her student instructors, Peregoy has seen the literacy intervention make a difference. “I think it’s a great program,” she says. “I see the children really progress.”

Next on the docket for Culatta is a book and further expansion of her literacy interventions. She and her students are writing a book that will outline the curriculum and include hundreds of early literacy activities for teachers to draw from. Culatta is also currently working to implement early literacy interventions in selected schools in Guatemala. She is working toward a more ubiquitous implementation in Latin America as well as the United States.

“I would like to see children who don’t have as much of a chance succeed at school,” Culatta says. “And I really believe they can have that chance with the right level of intervention and the right opportunities.”

Lisa Ann Jackson is the news editor for the Ensign and Liahona magazines.