Dennis Wright (left) and Robert Freeman have teamed up to create an archive of stories from the more than 100,000 Latter-day Saints who served in World War II.

By Lisa Ann Jackson, ’95

Church History and Doctrine

BYU professors gather stories of Latter-day Saint veterans.

Joseph R. Banks, ’48, slipped past the Nazi guards into the European countryside. He and three other escaped prisoners of war traveled by night for several days, restricting their movements until the middle of the night, when they could travel undetected.

One night as they crept along, Banks was startled by a voice. Suddenly a door opened in a house to his left. Light flooded out, illuminating him in his prisoner-of-war uniform, and a German soldier came through the doorway, shouting at him.

“Before I could think of what to do, I was startled . . . to hear myself respond with a calm, confident German phrase that obviously was appropriate to what he’d asked me,” Banks recalled. “He then replied to whatever I’d said with an almost cheerful, ‘Ja, Ja, Ja!’ . . . and went back into the house.”

When they were safely on their way again, Banks’ companions asked him what he had said. “I told them I had no idea what either he or I said, since I couldn’t speak German.”

For Banks the experience was a miracle and a reminder that he was not alone while he served in World War II. “It thrilled me to know that God was still watching out for me and that he cared for me.”

Banks’ story is one of almost 1,000 recorded in a growing archive of experiences of Latter-day Saint veterans (whether they were members of the Church of Jesus Christ during the war or joined later) housed in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections in BYU‘s Harold B. Lee Library. The archive, called Saints at War, was begun two years ago by Robert C. Freeman, ’85, assistant professor of Church history and doctrine, and Dennis A. Wright, ’73, associate professor of Church history and doctrine. The two have set in motion the only living archive of LDS veterans’ wartime experiences.

“About 1,100 World War II veterans die each day,” says Freeman. “It’s sort of a ‘speak now or forever hold your testimony’ moment.”

Freeman and Wright have found that many veterans choose to speak now. Veterans traditionally have kept their experiences to themselves. But for this project they have stepped forward to share and record their stories.

“It is really the spirit of Elijah turning the hearts of the children to their fathers and the hearts of the fathers to their children,” says Freeman.

Freeman’s interest in LDS veterans began when he taught an adult Church history survey course at BYU several years ago. At the end of a lecture on World War II, a class member told of his service in the war and how he had been deeply affected by Church support he received during the war. “It was a brief comment,” Freeman says, “but it stayed with me.” As Freeman researched for other classes and presentations, he realized that few first-person accounts of LDS veterans had been preserved. For Wright the project was compelling because his own father was a veteran of World War II, and he felt that these voices were worth preserving.

As Freeman researched for other classes and presentations, he realized that few first-person accounts of LDS veterans had been preserved. For Wright the project was compelling because his own father was a veteran of World War II, and he felt that these voices were worth preserving.

“If this is a time filled with wars and rumors of wars, these accounts could bring great insight and understanding and even encouragement to future generations, who may be faced with the same challenges that these young men and women were faced with,” says Wright.

With the help of up to eight student assistants at a time, Freeman and Wright gather and catalog submissions, conduct personal interviews, transcribe tapes submitted by veterans or their families, and compile veterans’ written histories.

From the archive have grown a book, Saints at War: Experiences of Latter-day Saint Veterans during World War II (Covenant, 2001); a KBYU documentary; a veterans conference held on campus in November 2001; and an online collection of selected stories.

Saints at War, which recently expanded to include the Korean conflict, the Vietnam War, and later conflicts of the 20th century, is an official partner of the Veterans History Project underway in the Library of Congress. “Saints at War serves as a focal point and established repository for materials from this underdocumented group,” says Sarah Dashiell Rouse, program officer for the Veterans History Project.

More than 100,000 Latter-day Saints served in the armed forces during World War II at a time when Church membership had not quite reached 1 million. More than 5,000 Saints perished during the war, which claimed more than 50 million lives on all sides of the conflict.

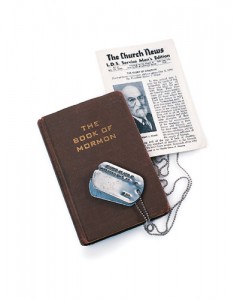

Latter-day Saint pilot Roland R. Wright (second from left) poses with his crew on the wing of the Mormon Mustang in 1944 or 1945. Wright and other LDS servicemen and women received special servicemen’s editions of the Book of Mormon and the Church News.

The stories often have a spiritual bent and run the gamut—including stories of protection, loss, and guidance. They tell of soldiers stealing quiet moments to study their servicemen’s scriptures. They describe spontaneous sacrament meetings held in bombed-out buildings, leaky tents, open fields, and even prisoner-of-war camps. They reveal methods LDS soldiers used to seek each other out—word of mouth, scribbled leaflets, and official invitations. One creative LDS chaplain added to the standard Christian crosses painted on his jeep a beehive, an angel Moroni, and the word deseret as clues forLDS servicemen and women.

Along with its focus on Latter-day Saints, the archive is unusual because it documents veterans from several nationalities on both sides of the conflict. When the war erupted in Europe in 1939, Church membership in Germany was third only to the United States and Canada. More than 500 German Latter-day Saints lost their lives in World War II.

Hans Max Boettcher, a veteran of the German Army, recalls his experience with other Latter-day Saints while at an Allied prisoner-of-war camp in the Italian mountains. Boettcher had served a full-time mission and had married a young LDS woman before being drafted. The only LDS prisoner in his camp, Boettcher learned that an old LDS friend was in a nearby camp. He was able to make contact with his friend, who in turn put him in touch with an American LDS chaplain, Royden C. Braithwaite, ’37. From their first meeting, records Boettcher, “[He] came every Sunday and picked me up for sacrament meeting in town.”

“These men and women didn’t set aside their religious conviction,” Wright says. “Even though they were carrying rifles and machine guns, they still found time to read their scriptures, take the sacrament, say their prayers, and share the gospel. In the most trying circumstances, their spiritual life did not end. In fact it became their sustaining force.”

In that way, says Freeman, the stories in the Saints at War archive become relevant to our lives today. “They not only give us the stories we want to know about their war experiences, but they also give us a pattern for living.”

Lisa Ann Jackson is an editor for the Liahona magazine and a freelance writer.

info: Veterans or their families can contribute to the Saints at War archive by sending submissions to saintsatwar@byu.edu or by calling 801-422-2820. Readers can find out more about the Library of Congress’ Veterans History Project at www.loc.gov/folklife/vets.