<p>This know also, that in the last days perilous times shall come. For men shall be lovers of their own selves, covetous, boasters, proud, blasphemers, disobedient to parents, unthankful, unholy, without natural affection, trucebreakers, false accusers, incontinent, fierce, despisers of those that are good, traitors, heady, highminded, lovers of pleasures more than lovers of God. —2 Timothy 3:1-4</p>

<p>This know also, that in the last days perilous times shall come. For men shall be lovers of their own selves, covetous, boasters, proud, blasphemers, disobedient to parents, unthankful, unholy, without natural affection, trucebreakers, false accusers, incontinent, fierce, despisers of those that are good, traitors, heady, highminded, lovers of pleasures more than lovers of God. —2 Timothy 3:1-4</p>

The apostle Paul’s warnings to his young disciple Timothy concerning the wicked conditions of the last days are being realized before our very eyes. In fact, it may be even worse than Paul’s dire description. We see all manner of sin–violence, crime, alcohol and drug abuse, immorality. Such evil seems to be escalating at an alarming pace. Just as the Savior prophesied concerning the conditions in the world that would precede his Second Coming, “iniquity [does] abound, the love of men [does] wax cold” (JS-Matt. 1:30) and “all things [are] in commotion; and surely, men’s hearts [do] fail them; for fear [has] come upon all people” (D&C 88:91).

Members of the LDS Church certainly find themselves in the midst of such world conditions. Parents often lie awake at night worrying about their children and wondering what they can do for a son or daughter who is surrounded by, and may be yielding to, temptations. Young people themselves feel enormous pressures–tugged and torn in different directions as they try to live the gospel and, at the same time, gain the acceptance of their friends.

“My parents really have no idea how hard it is to be a teenager today,” one LDS high school student despaired. “Almost all of my friends use alcohol and drugs and go to parties almost every weekend. Many are immoral and tell me how fun it is. When I tell them these things are against my religion, they make fun of me and call me names.”

Another teen described the tension he feels between his desire to live the gospel and his need to be accepted by his friends. He said, “I don’t know what it is; I guess it is a desire to fit in or to be popular. I am a little shy, and sometimes when I’m around my friends, I feel I have to make them like me. Then I do things I know are wrong, but if I don’t do these things, I am rejected and feel isolated.”

Days, weeks, and months of peer pressure can wear down the spiritual strength of youth and may cloud their view of right and wrong. Another LDS young woman eloquently described this process of eroding values: “From seeing my friends do things that were wrong, and not wanting to be made fun of, it is hard for me to fully understand what’s right and wrong, and so sometimes I do things I regret later.”

What can parents do to counteract the influences to do evil that assault teenagers today? How can they help the youth of the Church “put on the whole armour of God” (Eph. 6:11)? What can be done to help our children gain their own testimonies and spiritual strength? What must occur within the family to insulate children from evil influences? Is it better to raise children where there is a powerful LDS environment, or is it better to raise them where they have to stand up for their beliefs? These are but a few of the many questions parents ask themselves as they struggle to raise happy, competent, and faithful children in these trying times.

Fortunately, parents are not left alone in their efforts to raise righteous children in a wicked world. The prophets of God continually raise their warning voices and lovingly give us counsel to strengthen our families and heighten the spirituality of our children in order to overcome the temptations that seek to destroy them.

A study we recently completed showed that faith and family can indeed insulate young people from worldly ways by helping them put on the whole armor of God. The study revealed not only how LDS youth are faring as they struggle to live righteously in today’s world, but its results also offer parents and youth leaders some insight into what they can do to help their teenagers resist temptation.

In the following pages we describe our study and its results and implications. What we learned was not new or earthshaking; instead, we rediscovered what prophets, both ancient and modern, have always taught. So while it is comforting to have empirical data supporting gospel principles, we want to emphasize that the prophets of God have always testified that the home is the place where the lifesaving armor of God is best placed upon our youth. We hope, however, that the results of our study will present some old ideas in a new and helpful manner, reinforce the counsel of the prophets, and provide parents with practical guidance on how to arm their teenagers.

The Study

Some scholars have argued that the behavior of youth is not affected by their religious values, but rather by the religious environment or “ecology” in which they live (see Rodney Stark, “Religion and Conformity: Reaffirming a Sociology of Religion,” Sociological Analysis 45 [1984], pp. 27381; Rodney Stark, “Religion as Context: Hellfire and Delinquency One More Time,” Sociology of Religion 57 [1996], pp. 16373). However, we are convinced that LDS youth do internalize religious values and principles that guide them away from delinquency into acceptable and socially desired activities. Therefore, in our study we sought to determine which has the stronger influence on delinquency among LDS young people: religious ecology or the internalization of religious principles.

With the cooperation of the LDS Church Educational System, three samples were drawn from the prospective seminary enrollment lists of LDS 9th- through 12th-graders in three different geographical regions–the East Coast, the Pacific Northwest, and Utah County. We chose these three areas because they represent different religious ecologies. The Pacific Northwest has been identified by social scientists as having the lowest religious ecology in the United States, whereas the East Coast has a moderate ecology. On the other hand, Utah County has the strongest religious ecology in the country (see Stark, 1984, 1996).

Between 1992 and 1996 approximately 4,000 packets were sent to the parents of LDS youth in the three areas, requesting them to allow their teenager to participate in the study. We received 1,393 (74 percent) completed questionnaires from the East Coast sample, 632 (66 percent) from the Pacific Northwest sample, and 1,078 (62 percent) from the Utah County sample for a total of 3,103 respondents. Overall, 69 percent of the youth in the samples responded to the survey.

In our study we wanted to test factors that contribute to or discourage delinquency in teenagers. We defined delinquent behaviors as activities such as fighting, smoking, drinking, petting, sex, vandalism, stealing, and truancy. From the results we hoped to determine implications that could guide parents in helping their children resist temptation. Following are the categories on which we focused.

Peers. Extensive research, as well as common sense, has documented peers’ power to influence delinquent behavior. In the study we asked young people to identify the most significant deterrent to living gospel principles. A majority identified peers. One young woman reported that her friends have influenced her because of her desire for acceptance: “The strongest pressure to do bad has come from me wanting to fit in, seeing my friends do things which aren’t the best, and not wanting to be made fun of, wanting to have friends. I think sometimes I don’t fully understand what’s right and wrong in situations when it is not obvious.” Not only did she feel pressure from friends to participate in deviant behavior, but her friends confused her sense of right and wrong.

We included two dimensions of peer influence in our study–peer pressure and peer example. To assess the influence of peers in delinquent behaviors, we asked the youth to identify the number of their friends involved in delinquent behavior and the number of those friends that pressured them to participate. We also asked how many of their friends were members of the Church.

Religiosity. For generations people have assumed that training young people in religious values was a major factor in preventing delinquency and other unethical behaviors. In recent times, however, this “hellfire and damnation” theory has been challenged by many social scientists and completely rejected by others. To test the influence of faith and religion on delinquency, we surveyed five dimensions of religiosity: beliefs, private behavior, public behavior, spiritual experiences, and feelings of acceptance in an LDS congregation. Religiosity questioned issues such as church attendance, spiritual experiences, and personal testimony.

Family. Although teenagers are seeking forms of independence from parents, the family remains an important source of emotional support and social control during adolescence. We studied three aspects of the parent-adolescent relationship: connection, regulation, and psychological autonomy. Connection between parents and children refers to a positive, stable emotional bond that develops largely through the love and support parents give their children. Regulation refers to the rules, limit-setting, monitoring, and discipline parents establish for their teenage children. Psychological autonomy refers to the degree to which children are allowed to come to know and express their own thoughts, feelings, and opinions.

Questions about the family assessed if parents are married or divorced, if parents had been sealed in the temple, and if mothers work outside the home. The study also included questions about the parenting aspects mentioned above.

Summary of Results. Despite the arguments of some, our study showed that when raising teenagers, it doesn’t really matter where the family lives. LDS teenagers in all three religious ecologies responded similarly to the questions about delinquency; only a few statistically significant differences surfaced in the analysis. It is easy to long for some sort of “spiritual Shangri-la,” but, unfortunately, there is no such place. The fortunate flip side of the coin is that it doesn’t matter. In this study geography or religious ecology was insignificant. Teens face substantial peer pressure regardless of where they live, and, more important, they can be strong in the gospel wherever they reside. Truly, Zion is “the pure in heart” (D&C 97:21)–a spiritual condition rather than a geographical location.

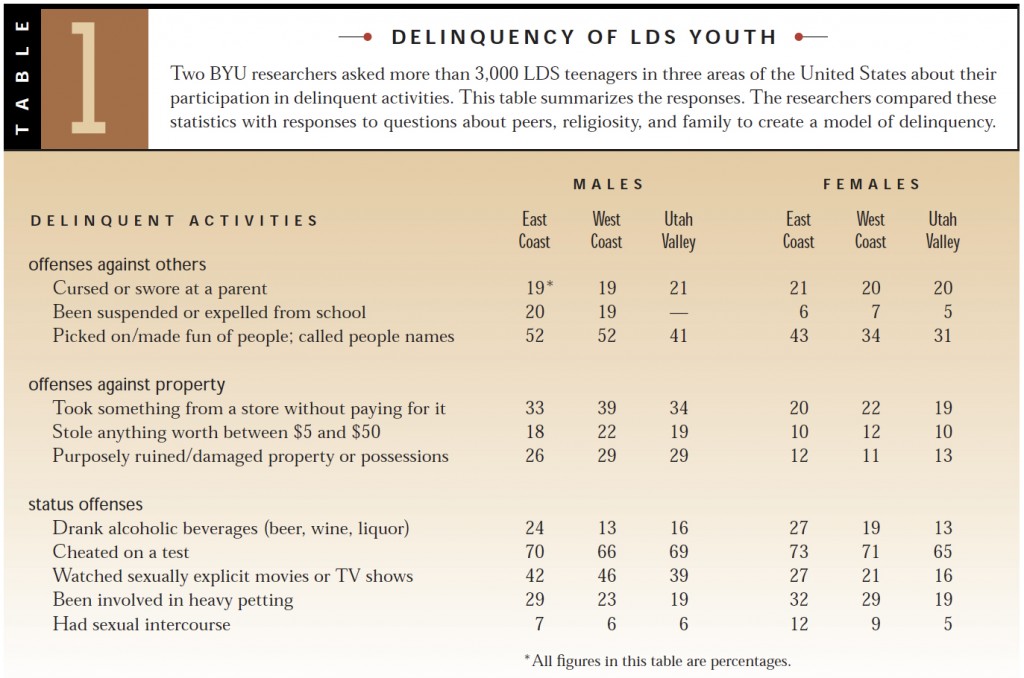

The good news of the study is that the youth of the Church reported significantly lower levels of delinquency than the average youth in the nation. For example, more than 60 percent of high school seniors nationwide have smoked cigarettes whereas only 20 percent of LDS high school seniors have done so. More than 80 percent of the seniors in the country have drunk alcoholic beverages compared to about 20 percent of LDS seniors. And nationally 73 percent of the male and 56 percent of the female high school seniors have had sexual intercourse; among LDS youth, only about 10 percent of the males and 17 percent of the females have had sex. When compared with national averages, the youth of the Church come out markedly on top. (National statistics taken from L. D. Johnston, J. G. Bachman, and P. M. O’Malley, Monitoring the Future [Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, 1993], pp. 250, 277; P. L. Benson, The Troubled Journey: A Portrait of 6th12th Grade Youth [Minneapolis, MN: Search Institute, 1990], p. 54.)

The bad news is that although LDS teens seem to be generally less delinquent than their national peers, they do make mistakes and do engage in delinquent behaviors that are against the standards of the Church (see table 1). When we asked, “What has been the strongest temptation in your life to not live the standards of the Church?” sexual temptation was the challenge most frequently cited by the teens.

“The strongest temptations in my life,” one young woman reported, “have been boys and sex. Satan is so strong! He finds a way to make it look like it’s not that bad.”

Another young woman reiterated this sentiment: “The strongest temptations in my life have been boys (sex), peer pressures, and a few little things. Satan is so strong! I wish so badly that I could go back and undo some of the things I have done.”

Many similar comments from both young men and young women seem to confirm the concerns expressed by President Ezra Taft Benson about what he called “the plaguing sin of this generation” (“Cleansing the Inner Vessel,” Ensign, May 1986, p. 4). “Sexual immorality is a viper that is striking not only in the world, but in the Church today. Not to admit it is to be dangerously complacent or is like putting one’s head in the sand” (God, Family, Country: Our Three Great Loyalties [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1974], p. 239).

However, parents can influence their youth for good and help them avoid these and other temptations. In each of the three areas we studied–peer influences, religiosity, and family influence–the statistical analysis and the comments of the teenagers revealed specific steps parents can take to help their children. In the sections that follow, we present the results of our study in each of the three areas and summarize a few suggestions for parents.

Peer Influences

The youth of the Church are exposed to considerable pressure from their friends to participate in illegal, immoral, and inappropriate behaviors. In our study, about 40 percent of the boys said friends had pressured them to beat up other youth, and some 25 percent of the girls reported they had been pressured to shoplift. More than three out of four LDS youth had felt pressure from friends to cheat on tests in school, and nearly half indicated they had been pressured to participate in immoral activities such as watching pornographic movies, petting, and engaging in sexual intercourse. Peer pressure was most pronounced for offenses such as drinking, smoking, using drugs, and participating in sexual activity.

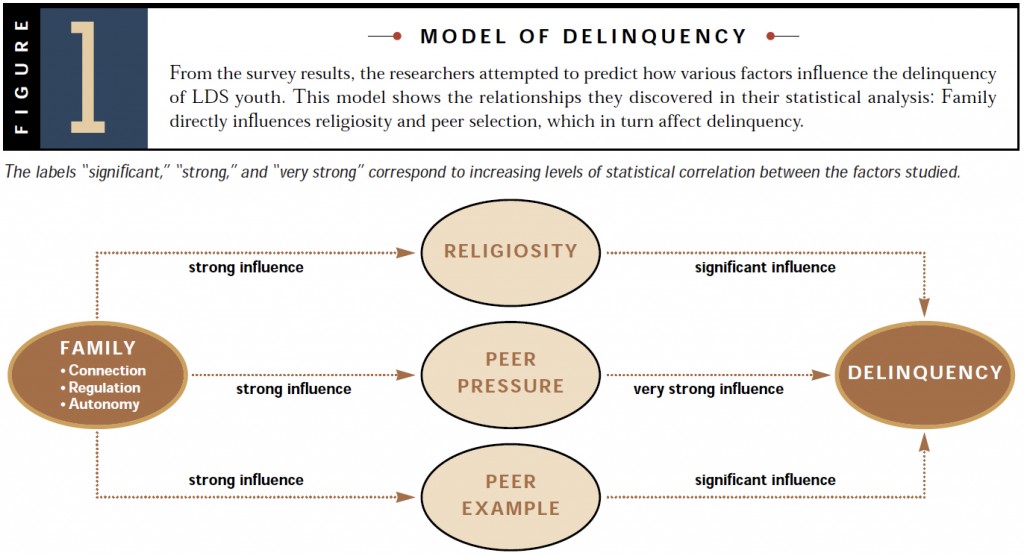

Our statistical analysis of the youth’s responses showed a strong relationship between peer pressure and delinquency. Peer example also makes a statistically significant contribution (see fig. 1).

One young woman explained the negative influence of peers on both values and behavior: “Public schools expose you to very awful, vulgar language and gestures. I’m forced to see and hear the bad things they do and say. A year ago I had some bad friends who pressured me to do bad things. At first it wasn’t such obviously bad things. But when I’d lower my standards to their level, they’d lower theirs more. Finally, with the help of my parents, I went to my bishop and repented.”

An important implication to emerge from this study is that parents should work to influence the quality of friends with whom their teenage children associate. “My friends have been the strongest pressures to live the standards of the Church,” wrote one young woman. “I know I’ve been blessed with good friends who are members of the Church and who have helped me be a better person. I can see the effects bad friends have on people, and I’m thankful for the ones I have.”

Influencing children’s friendships is not an easy task for parents. But there are some things parents can do to enhance the probability that their teens will become involved with good friends. Probably the most effective parental effort is encouraging children to participate in groups, organizations, and activities that will involve them with other good teenagers. Several youth credited their extracurricular activities with linking them to supportive friends. For example, one young woman said, “I usually made friends with people who were in similar activities as me, like track and cross country. I was also in a few accelerated classes and got to know the kids in them who were good kids and who were committed to school.”

Teens can be encouraged to participate in worthwhile school, church, and community activities such as athletic teams, choirs, bands, honor societies, community drama clubs, or service organizations. Such activities will provide good associates and will keep teens busy in wholesome activities. One young woman credited her parents for supporting–through paying extra fees, providing rides, and attending activities–her extracurricular activities. Such support will help students stay involved and enable parents to help determine the kind of peers who will influence their children.

Another good way for parents to help their teens develop positive friendships is to make their home available as a place to hang out. “My parents always encouraged me to invite my friends over, which in turn encouraged me to have friends that I wasn’t ashamed to have in our home,” commented one young man.

Another youth wished her parents would have been more hospitable to her friends. She wrote, “I wish they would have encouraged me to have more activities at our house. The trials I faced always happened at someone else’s home. I don’t think my friends would have even considered doing certain things in our home.” Parents can increase the attraction by making their teenagers’ friends feel welcome in the home. This not only strengthens friendships between the youth, but also creates ties between parents and their children’s friends.

Other ways parents can help their children associate with positive peers include choosing to live in a neighborhood with a low rate of delinquency, infrequent gang activity, little drug use, and reputable schools. Parents can develop friendships with families whose children would be good friends for their own, with the hope the teens will also become friends. In addition, parents can teach friendship skills to their teens so they in turn can have more choices of friends.

Parents should assist their teenagers in developing the ability to resist pressures from friends to participate in immoral or delinquent activities. The data, as well as the teens’ written comments, make it very clear they are continually exposed to powerful pressure from peers. Regulation, or family rules, often provide teens with behavioral boundaries and an “excuse” to use to get out of participating in an inappropriate activity. The internalization of religious principles will also help youth gain strength to resist peer pressure.

Assisting teenagers to associate with other youth who are involved in worthwhile activities and who live the standards of the gospel will significantly increase the likelihood that teens will have a safe journey through adolescence and mature into competent young adults.

What parents can do to help children manage peer influences

• Encourage teens to participate in good groups, organizations, and activities.

• Make the home available as a place to hang out.

• Make teenagers’ friends feel welcome in the home.

• Choose a neighborhood with reputable schools and low rates of delinquency.

• Develop friendships with families whose children would be good friends for your own.

• Teach friendship skills.

• Set family rules and boundaries.

Religiosity

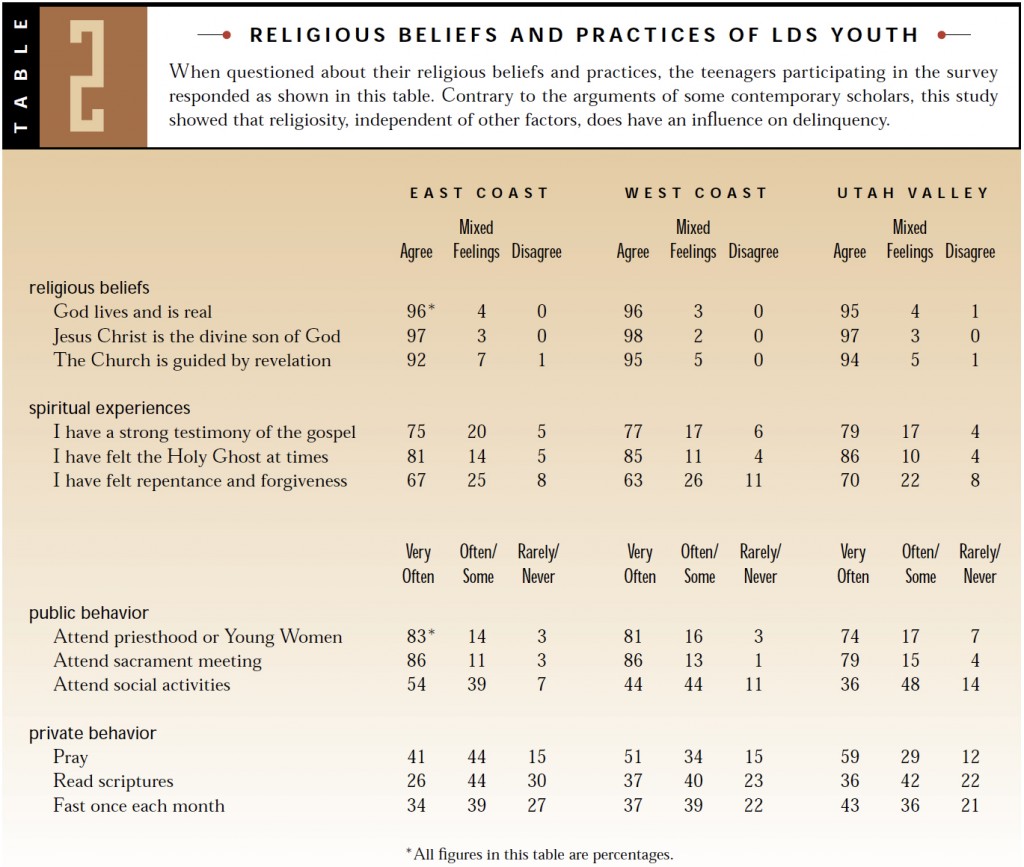

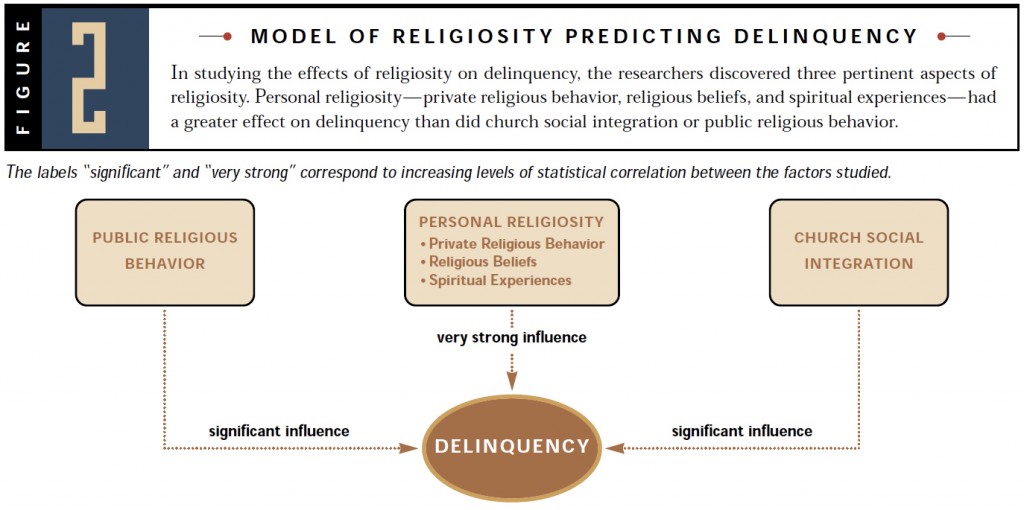

The high level of religiosity reported by LDS youth in the survey is noteworthy (see table 2) and shows that LDS youth across the country have deeply held religious convictions and are generally striving to live the standards of the gospel.

Perhaps the most important finding of the study is that religiosity, independent of peer influences, does indeed have a significant effect on the behavior of LDS youth. The statistical correlation clearly indicated that religious values, beliefs, and experiences are directly related to the avoidance of delinquency. LDS youth who believe gospel truths, who have made religion an important part of their lives, and who have experienced the spiritual fruits of their beliefs participate in less delinquent behavior than LDS youth who manifest less religiosity.

Another important result of the study was the identification of specific dimensions of religiosity that appear to make the biggest difference for youth (see fig. 2). The study showed private religious behavior, religious beliefs, and spiritual experiences to be highly correlated; hence, we grouped those three elements under one category: private religiosity. Private religiosity was the strongest predictor of delinquency among LDS teenagers: those youth who have internalized the gospel avoid delinquency to a greater extent than those youth who have not.

Two other factors of religiosity also proved to be correlated with delinquency, but less so than private religiosity. Social integration–feeling accepted in the ward and among other LDS youth–and public religious behavior, such as church attendance, significantly contributed to predicting delinquency.

In comparing these three dimensions of religiosity, it appears that the key to deterring delinquency and immoral behavior among LDS youth is not merely getting the youth into the Church, but rather getting the Church (personal testimony) into the youth.

Many youth who participated in the study eloquently identified their testimonies or reliance on their Heavenly Father as a source of strength in resisting temptation. One young woman said, “The most important influence that has helped me through negative pressures and temptations is the knowledge that I could turn to my Heavenly Father for purpose and direction.” Another youth wrote, “In junior high I prayed diligently and sincerely for a good group of friends. Answers and direction came that I knew were not my own. My testimony of the gospel brought a peace that sustained me during those difficult times.”

This study confirms what Elder James E. Faust taught several years ago as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles: “What seems to help cement parental [and Church] teachings and values in place in children’s lives is a firm belief in Deity. When this belief becomes part of their very souls, they have inner strength” (“The Greatest Challenge in the World–Good Parenting,” Ensign, November 1990, p. 34).

Elder Joe J. Christensen of the presidency of the Seventy has further emphasized the importance of creating an environment to build personal testimonies in children:

One of the most effective ways to gain personal spiritual experiences and testimony is to become personally involved in serving, searching and pondering, and praying….We parents need to take seriously our responsibility to provide religious training in the home so that our children will in turn take religion seriously and personally….Praying, holding family home evenings, and studying the scriptures with our children are important foundations. As we strive to create a spiritual environment, our family members can be led to those experiences that will help them build their own personal testimonies. [One Step at a Time (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), pp. 9092]

We discovered that some dimensions of religiosity are more important than others in explaining delinquency. Private religious practices and spiritual experiences were more influential in deterring delinquency than public practices such as attendance at meetings. Thus, parents should help their teenage children develop habits of personal religiosity. For example, encouraging the regular practice of personal prayer can be a powerful tool to help teens develop personal religiosity and to resist temptations. Many families emphasize family prayer so much that they neglect to encourage children to pray personally. Family prayer definitely is good, but it should not substitute for youth having their own daily personal prayer.

Parents can teach their children by precept and example. The righteous example of parents who have made the gospel the very core of their lives provides youth with a living object lesson. Nothing will turn youth away from gospel teachings more than seeing their parents not practice what they preach. Parents must first internalize gospel principles if they expect their teenage children to do likewise.

One youth emphasized the power of parental example: “My parents’ examples in living the teachings of Christ helped me internalize the gospel’s principles in my life. The most important thing was just seeing in them that the gospel and Church were central to their lives. It was evident in every aspect of their lives.”

If we want our children to have testimonies of the gospel of Jesus Christ, to internalize its principles into their own lives, and to live by high standards of purity and integrity, we must do the same.

Parents can also help their children internalize the gospel by holding regular family prayer, scripture study, and home evening. There is spiritual power in these family religious practices. We should participate in these activities with our families not because we feel compelled to or are merely going through the motions, but rather because the gospel is the center of our lives and because these are the manifestations of our love for the Lord and our families.

Perhaps every parent has felt frustrated at times in trying to faithfully hold family prayer, scripture study, and home evening when children are restless and nothing seems to be “sinking in.” The youth in our study, however, made comments that should encourage parents. One teen said, “I know I was a pain in the neck to my parents when it came to family prayer and family home evening, but I am thankful now that they didn’t give up. It had more influence than I was willing to admit at the time.” Another wrote, “I wish my parents would have had regular family home evening and family prayer. We did it once in a while, but I wish it had been more regular. I probably would have hated it at the time, but now I can see its importance.”

The prophets of God have continually promised us that not only will gospel understanding and testimony increase when we faithfully attend to these family practices, but also love, harmony, and closeness within the family will grow.

In addition, parents can teach the practical applications of gospel principles to their youth. Parents can help their children understand how gospel principles are actually utilized in their daily lives. They can “liken all the scriptures” (1 Ne. 19:23) to themselves and ask questions of teens that will inspire them to find their own applications. Youth are more likely to live the standards of the Church when they see examples of the blessings of obedience and when they have explanations as to why they should live these standards.

By providing opportunities for spiritual experiences, parents can help their youth see those practical applications. Family outings to the temple for baptisms, family service projects, family testimony meetings, father’s blessings, baptisms of family members, and other special occasions are examples of important opportunities for teenagers to feel the Spirit.

Encouraging youth to come to know the truthfulness of the gospel for themselves will also help youth internalize the gospel. With every gospel principle taught and testimony borne, parents can assure their teens that they can gain their own testimony. Parents should not try to solve all the problems their teenagers face or attempt to answer all their questions. Rather, encourage them to pray to their Heavenly Father about their concerns or needs.

A youth wrote, “My parents taught me how important personal revelation is and how I could find answers in the scriptures and receive answers to my prayers.” We can teach them skills, we can direct them and guide them to the source. But the source must be the words of the Lord. It will mean more to them to find answers to gospel questions and life’s difficult dilemmas through their own searching than from parental teaching.

Personal spirituality–the internalization of gospel principles anchored in a divine witness of the truthfulness of the gospel–is what clothes youth in the armor of God and empowers them “to quench all the fiery darts of the wicked” (Eph. 6:16). At the center must be an understanding and application of the atonement of Jesus Christ and a testimony of his divinity. Only on this foundation can religiosity have any lasting protective power for the youth.

In our study we anticipated that strong LDS families would not only influence teenage children to abstain from delinquent behaviors, but also assist their children to choose desirable friends, to resist negative peer pressures, and to internalize religious values. The direct effect of family on delinquency, however, was not statistically significant in the results. This should not be interpreted to mean that the family does nothing to deter delinquency in youth. The effects are indirect. The influence of the family fundamentally underlies both peer influence and religiosity.

Three family attributes–connection, regulation, and psychological autonomy–demonstrated strong statistical relationships to the spirituality of teenagers and their selection of friends, which in turn significantly influence delinquency (see fig. 1). This was true regardless of family structure (one- or two-parent families) and maternal employment, which were not important predictors of delinquency. When it comes to giving LDS teens the strength to resist temptations, the family matters.

What parents can do to help youth internalize gospel principles

• Be a good example.

• Hold regular family prayer, scripture study, and home evening.

• Teach practical applications of gospel principles.

• Provide opportunities for spiritual experiences.

• Encourage youth to come to know for themselves.

Increasing the Family’s Influence

Although the family may have an indirect relationship in helping teenage members avoid delinquent activity, that relationship is significant. This study revealed that parents who are connected with teenagers, who regulate their behavior, and who grant them psychological autonomy strongly affect the selection of friends, resistance to peer pressures, and internalization of religious values and principles, all of which influence delinquency.

Family Connection.

It is important that parents maintain supportive feelings with their teens through unfeigned love. “My parents are very affectionate,” one youth stated. “They always hug me and tell me that they love me. They have often expressed their love for each other and for us in front of all the kids. I am complimented for the good things I do and my parents often tell me that they are proud of me.”

Unfortunately, there were also some negative comments and pleas for acceptance from their parents. “I wish my parents would respect me more–see me as a person not as a robot,” one youth declared. “I wish I could receive more affection from my dad. Also more encouragement and recognition of my accomplishments and not so much focus on my shortcomings.” Parents are encouraged to verbalize their feelings of love and acceptance of their teens. A hug, an arm around the shoulder, and kind, loving words will help keep parents and teens connected.

Family connectedness requires time, especially one-on-one time. In a recent article in a national news magazine, the author observed that “kids don’t do meetings. You can’t raise them in short, scheduled bursts. They need lots of attention” (“The Myth of Quality Time,” Newsweek, May 12, 1997, pp. 6265). The youth in the study echoed this point in their comments. One young woman articulated her desire for more time with her parents. “I wish my parents would listen to me on an individual basis more–especially when I am having a bad day. I wish they would listen without giving advice, getting upset, or trying to fix the problem. Five to ten minutes of individual one-on-one time makes a big difference.”

Many of the young people reported that some of their most memorable and profound family experiences came in simple, spontaneous ways like talking at the dinner table with Dad or shopping for a prom dress with Mom. As one young woman described,

There are two specific places above the rest that I hold dear to my heart and view as great places of learning. This may sound strange, but they are my parents’ king-sized bed and the kitchen table. My family almost always eats dinner together. This is where we can discuss not only our daily activities, but often much more. We sometimes get into deep discussions about a gospel subject or talk about how we would deal with a certain problem that my dad had encountered at his office. These little things have taught me a lot. As for the bed, it had to be king-sized so that all six of us kids could sit on it. This is a great place for the children to snuggle up with my parents and just talk. I have really felt comforted, guided, and taught while on the bed with Mom and Dad and my brothers and sisters.

A young man told of a time when, after he had broken up with his girlfriend, he was sitting on the curb feeling quite forlorn. His father came out and sat on the curb with him, put his arm around him, hugged him, and then shared his own experience when he felt the same kind of pain. The young man stated that he could finally “relate to my dad,and I knew that he knew how I felt. I felt a special closeness to him then.”

As is evident from every parent’s experience, as well as from these comments, raising teenagers is a time-intensive endeavor. Some of the time can be scheduled, and some time must be given on the spur of the moment, when it is not convenient. Occasions such as children gathering on their parents’ bed or a father observing a dejected son sitting on the curb mean seizing a moment of unplanned parental time.

Numerous young people in the study pled for their parents to be more liberal with praise and generous with forgiveness. The youth acknowledged their mistakes but were disappointed that their parents directed most of their attention to such misdeeds and neglected their accomplishments, however modest. Many young people indicated they see mistakes as learning experiences they want to put in the past, but their parents continue to rehash the mistakes.

What parents can do to foster family connectedness

• Spend one-on-one time with teenagers.

• Express love to teenage children.

• Spend time together as a family.

• Be liberal with praise.

• Be generous with forgiveness.

Family Regulation.

As all parents will readily admit, monitoring a teenager can be an arduous task, and discipline is rather unpleasant. Parents should negotiate family rules, principles, or guidelines with their teens. The family may function with just a few basic principles or may have a rather elaborate set of detailed rules, such as a family constitution. What matters is that teens have some core principles to guide their behavior.

Allowing youth’s input in the establishment of family rules is advantageous. As one young man wrote, “My parents allowed me to be involved in our family rule-setting. I helped set the expectations of conduct as well as the punishments. This way I can’t complain too much when I get punished for messing up.”

Compliance to family rules requires that parents monitor their teenager’s behavior. This can be done through talking and listening to teens to gather information concerning their friends, the activities in which they are involved, where they go when away from home, etc. Parents should watch for danger signs such as declining school performance, changes in friends, staying out late, sudden personality changes, and complaints from teachers.

Then comes the more difficult parental behavior–discipline. Most parents want to be friends with their teenage children and thus tend to neglect enforcing family rules. It is critical that teenagers learn that their behavior has consequences. They need to learn they are responsible for their actions at home, at school, in the neighborhood, and at Church. As a part of the administration of discipline, parents should calmly, yet firmly, discuss the violation of the rule and explain the impact such behavior has on the teen and others with whom he or she associates. Teens often define discipline as rejection; thus it is necessary for parents to express their love for the child at this difficult time.

Interestingly, very few of the youth complained about the number or strictness of family rules, whereas many more wished their parents had been more strict and had given them greater guidance through these difficult years. One young woman reported, “I know I would have far more respect for my parents if they more clearly set boundaries for me. For instance, I recall my dad repeatedly told me to do my job for the week–the dishes. I kept putting it in the back of my mind, not wanting to do them. My dad gave up and did them himself. I remember being frustrated at him for not setting his foot down and demanding that I heed him despite the fact that I didn’t want to do them.”

A young man said, “Sometimes I wish my parents were more strict. I wish they were more like parents and less like my buddies. Sometimes you just need a parent to put his foot down instead of always saying ‘What you think is all right with me.'”

Another caution for parents is not to use love withdrawal or excessive guilt induction as discipline. These disciplinary techniques destroy a teen’s confidence in his or her ability to make good decisions and diminish feelings of self-worth.

What parents can do to foster family regulation

• Establish family rules.

• Assign all family members household chores.

• Enforce rules.

• Show increased love following reprimand.

• Monitor teenagers’ behavior.

Psychological Autonomy.

Another implication from this study is the importance of parents granting psychological autonomy to their teenage children. Some of the young people in the study who reported a history of delinquent or immoral behaviors noted their parents were intolerant of opinions or views different from their own.

“When I try to talk to my parents, they don’t take my viewpoint or opinions seriously,” one girl wrote. “They make me feel like my ideas and desires are stupid.” Another wrote, “My father is so opinionated and feels that he is always right. He is very smart, so when I present a different viewpoint or argument, he immediately swats it down. I don’t think he ever takes my thoughts or feelings seriously.”

Parents need to encourage their children to share their thoughts and feelings and to react to them with respect. When a teen blurts out an idea that parents think is wrong, even weird, they need to be careful not to squelch the teen’s confidence. Patience, long-suffering, and helping the youth explore the idea and its consequences are much more effective. Subtle guidance and gentle persuasion will generally help a young person develop opinions, ideas, and attitudes consistent with gospel principles.

Cultivating these three family attributes–family connection, family regulation, and psychological autonomy–can be influential not only in helping youth learn to apply gospel principles to their own lives, but also in counteracting the negative peer influences they face daily. Family and faith go hand in hand in helping adolescents resist temptation.

As one young woman declared, “My family and the gospel are the two most important influences in my life. Through them I have been able to overcome the challenges and pressures I face.”

What parents can do to foster intellectual autonomy

• Encourage teenagers to share their feelings, opinions, hopes, and desires.

• Express acceptance of teenagers’ attitudes, opinions, or feelings, even if you disagree with them.

• Help teenagers to explore the source of attitudes or feelings and their long- and short-term consequences.

• Allow teenagers the opportunity to be their own person of worth.

• Do not use withdrawal of love or induction of guilt to change teens’ opinions, feelings, or ideas.

Conclusion

Our research discoveries are not new or earthshaking, but simple common sense. The prophets, both ancient and modern, teach the same concepts. President Boyd K. Packer testified,

[The] shield of faith is not produced in a factory, but at home in a cottage industry….

Lest parents and children be ‘tossed to and fro,’ and misled by ‘cunning craftiness’ of men who ‘lie in wait to deceive’ (Eph. 4:14), our Father’s plan requires that, like the generation of life itself, the shield of faith is to be made and fitted in the family. No two can be exactly alike. Each must be handcrafted to individual specifications.

The plan designed by the Father contemplates that man and woman, husband and wife, working together, fit each child individually with a shield of faith made to buckle on so firmly that it can neither be pulled off nor penetrated by those fiery darts.

It takes the steady strength of a father to hammer out the metal of it and the tender hands of a mother to polish and fit it on. Sometimes one parent is left to do it alone. It is difficult, but it can be done.

In the Church we can teach about the materials from which a shield of faith is made: reverence, courage, chastity, repentance, forgiveness, compassion. In church we can learn how to assemble and fit them together. But the actual making of and fitting on of the shield of faith belongs in the family circle. Otherwise it may loosen and come off in a crisis. [“The Shield of Faith,” Ensign, May 1995, p. 8]

There is protective power in genuine gospel living, and the home can be a safe haven from the evils of the world. At times, raising teenagers may seem to be an impossible task in the face of the evils seeking to lead youth astray in contemporary society. But parents feeling under siege can take courage from the spiritual insight of Elisha. The king of Syria desired to capture Elisha to stop him from advising the king of Israel. During the night, the Syrians surrounded with horses and chariots the city where Elisha was staying. A young servant boy exclaimed, “Alas, my master! how shall we do?” Elisha assured him, “Fear not: for they that be with us are more than they that be with them.” The servant’s eyes were then opened, and he beheld the “mountain was full of horses and chariots of fire” (2 Kings 6:1517).

Parents today can take hope from the same assurance: They that be with us in raising our children in righteousness are more than they that be with them seeking to involve our children in sin. The armor of God placed upon children by faithful and loving parents and the shield of faith obtained through internalizing the gospel can indeed help protect our youth as they daily encounter the fiery darts of a wicked world.

Brent L. Top is an associate dean of religious education and a professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU. Bruce A. Chadwick is a professor of sociology and the past director of BYU’s Center for Studies on the Family.

Rearing Righteous Youth of Zion, a book recently released by Bookcraft, contains a more complete report of this study, including a detailed statistical presentation and an in-depth discussion of the study’s implications for youth, parents, and youth leaders.