By Brent L. Top, ’76, Bruce A. Chadwick, and Matthew T. Evans, ’03

Scholars study how friends, faith, and family influence the sexual morality of youth.

In the early days of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Prophet Joseph Smith prophesied that the elders of Israel “would receive more temptations, be more buffeted, and have greater difficulty” from sexual immorality than from any other single challenge.1 Right before our eyes we are seeing the fulfillment of this prophetic declaration.

All of us, young and old alike, are bombarded with images of immodesty and immorality. We continually hear “sex talk” ranging from subtle innuendo to graphic descriptions or depictions. That which was once considered sacred, or at least private, is now spoken of casually and with little reverence. Those who speak up for moral values and who advocate chastity before marriage and fidelity within marriage are often put down as being provincial and unsophisticated. It is becoming increasingly difficult to “let virtue garnish [our] thoughts unceasingly” (D&C 121:45) when the rest of the world seems to have, as President Boyd K. Packer of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles described, “a preoccupation—even an obsession—with the procreative act.”2

More and more individuals and families are feeling the devastating physical, emotional, and spiritual effects of immorality. There has been a steady increase in children born out of wedlock, sexually transmitted diseases, addiction to pornography, and sexual abuse. Younger and younger children are exposed to and involved in immoral activities. Recent national studies report that nearly two-thirds of graduating high school students have engaged in premarital sexual intercourse3 and that about 20 percent of young teens have experienced sexual intercourse by age 15.4 Among young women, some 80 percent have had sex before age 20,5 and the proportion of young women having sex before age 15 increased from 11 percent in 1988 to 19 percent in 1995.6

These frightening trends generate questions about how Latter-day Saint (LDS) teens are faring in this morally polluted environment. What is their level of participation in sexual activities? What are the factors that discourage teenage sex? What, if anything, can parents or youth leaders do to help strengthen teens? These questions motivated a major study of LDS youth that we have conducted in recent years. What we discovered, however, is not earthshaking. Instead, we found empirical support for the teachings of prophets and apostles. Although it is certainly gratifying to have such evidence, we do not need an academic study to convince us that living the gospel actually works! Our hope, however, is that the results of this study will reinforce these age-old principles and provide some practical guidance on how we can best clothe our youth in the “armour of God” that will insulate them against the “fiery darts” of immorality (see Eph. 6:11–17).

THE STUDY

With the cooperation of the Church Educational System, we drew samples from the prospective seminary enrollment lists of ninth- through 12th-grade students; more than 5,000 LDS teenagers participated in the study. Samples were selected from three regions in the United States, each representing a different religious ecology, or climate: Utah County has a very high religious ecology, the East Coast has a moderate ecology, and the Pacific Northwest has the lowest religious ecology in the country. A sample from Great Britain was added since it represents an exceptionally low religious ecology. Finally, youth from Mexico were studied to ascertain whether language and culture make a difference.

For this study we combined heavy petting, oral sex, and sexual intercourse into a statistical measurement of sexual activity. We conducted an extensive review of the social-science literature to identify those factors that explain premarital sex among high school students: peer influences (example and pressure), religiosity (religious beliefs, public religious behavior, personal spirituality, family religiosity, and acceptance in a local congregation), pornography, and family influences (family structure, parental regulation, family connection, and psychological autonomy).

We used three statistical procedures to analyze the data from our study. First, simple percentages showed the proportion of LDS students who hold various beliefs or participate in particular behaviors. The second procedure was to calculate the correlations between two variables at a time; these bivariate correlations isolate the relationship between variables, without considering other influences. Third, we used structural equation modeling, which allows for several factors to compete simultaneously in explaining sexual activity. This modeling determines the strength of the various influences, while taking others into account, and identifies both direct and indirect effects of a factor.

FINDINGS

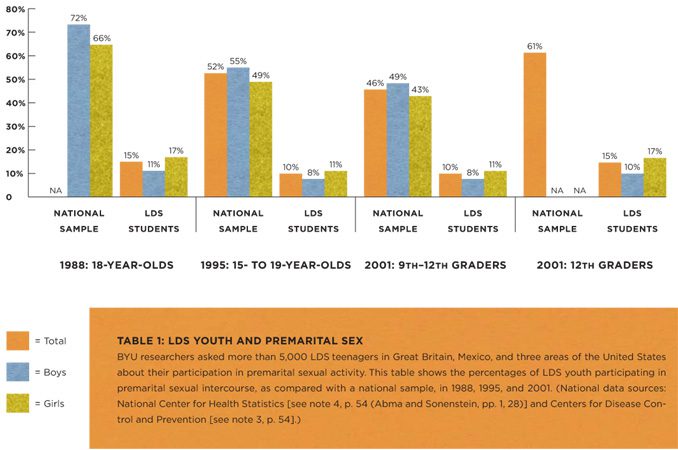

Some great news, as well as some very disturbing news, emerged from this study. LDS high school students’ rate of premarital intercourse is significantly lower than the national average (see table 1, p. 49). Nearly half of high school students across the nation are sexually experienced, as compared to 10 percent of the LDS high school students. The youth of the Church, to a large degree, are avoiding sexual immorality.

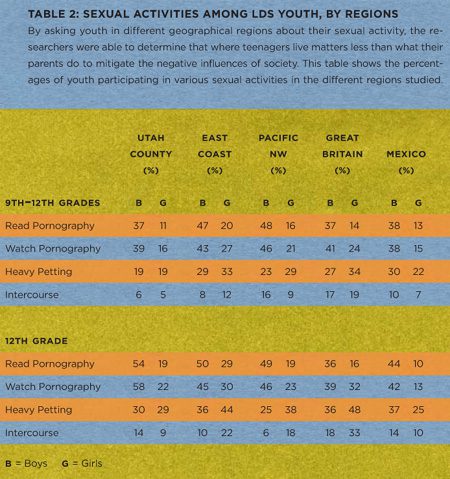

Another piece of good news was the similarity in rates of premarital sexual behaviors found in the various geographical areas or religious ecologies (see table 2, p. 50). Some scholars argue that religion’s influence on delinquency—including premarital sex—is a type of social control, that religious youth living a high religious ecology have lower rates of delinquency because of social pressures from other religious individuals.7 Contrary to those arguments, this study showed that where you live matters considerably less than what you do in your home and what goes on in the hearts of your children. Living gospel principles, whether you are in a predominantly LDScommunity or whether you are the only Latter-day Saint family in town, insulates your youth from the moral pollution of society and gives them strength to resist temptations.

Unfortunately, all is not well in Zion! The surrender of even one of our youth to sexual temptation is too many; while 10 percent is lower than the national average, it is still too high. In addition, it is troubling that nearly half of the LDS 12th-grade boys have seen pornographic movies (see table 2). Also disturbing is the finding that, except in Utah and Mexico, LDS young women had significantly higher levels of petting and sexual intercourse than young men. (The differences between young men and young women widens for high school seniors, as noted in table 2.) This is opposite of the national trend, where more young men are sexually active. Why the LDSyoung women in these regions were more sexually active cannot be definitively explained by this study, but a logical explanation emerged from discussions with young members of the Church. It is likely that young women living in these areas were “hanging out” with and dating young men who pose a higher risk. These high-risk young men are older than the girls and do not share the same religious or moral values prohibiting premarital sex. In addition, in American society young men tend to be the instigators in dating relationships and sexual activities. LDS young men, therefore, have greater control over whom they date and over the sexual overtones in a relationship.

Predicting Premarital Sex

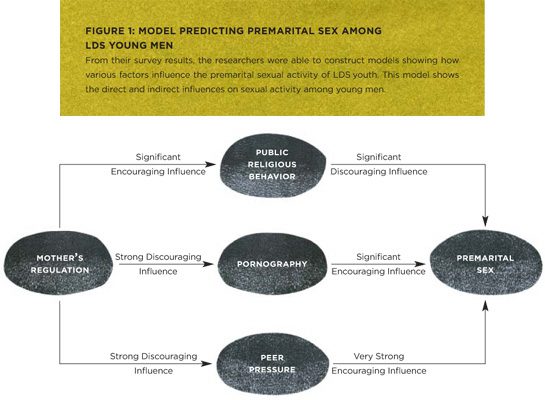

Among young men, peer pressure emerged as the strongest factor influencing premarital sexual behavior, followed by religiosity and exposure to pornography (see figure 1, p. 52). Interestingly, mother’s regulation had a strong indirect effect through peers, religion, and pornography. The model explained nearly 60 percent of the sexual activity of the LDS young men.

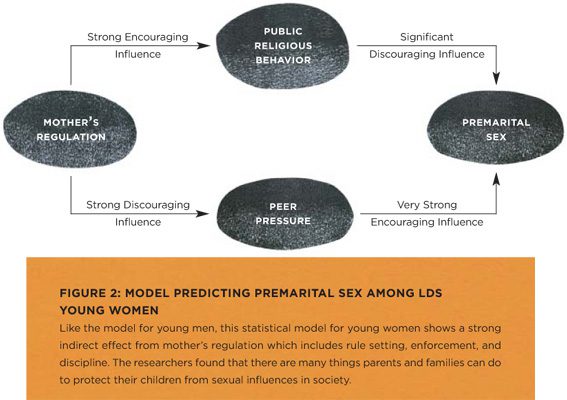

Although the results for the young women were similar (see figure 2, p. 53), there were a couple of notable differences. First, peer pressure was an even stronger factor. Second, pornography did not have a significant influence. Again, religiosity was significant, and mother’s regulation had a strong indirect effect. These three factors—peer pressure, religiosity, and mother’s regulation—explained over 72 percent of the young women’s sexual activity.

THE INFLUENCE OF PEERS Peer pressure has a very strong influence on sexual behavior (see figures 1 and 2). Among the young women in Utah County who had been pressured by their friends to participate in sexual activity, 36 percent had given in to the pressure. However, of the Utah County young women who had not been pressured, only one percent had participated in sex.

Because of the strong influence of peer pressure and the strong relationship of peer pressure to peer example, peer example did not emerge as a significant factor in the structural equation model. However, by itself peer example is a factor. Friends who have had sex, yet don’t pressure their LDS friends, produced fairly strong bivariate correlations. If LDS youth report that “most” or “all” of their friends have had sexual intercourse, then a sizable proportion of these youth have done so themselves. For example, among the young men living on the East Coast who reported that “none” of their friends had experienced sex, only 1 percent had engaged in intercourse themselves. On the other hand, among the young women along the East Coast who indicated that “most” or “all” of their friends had experienced intercourse, 31 percent had participated. This suggests that when teens justify associating with friends who participate in inappropriate behavior by claiming, “They don’t try to get me to join them,” parents should be leery. Just the example of friends engaging in immoral behavior influences young people.

Another interesting finding is the relationship between the proportion of LDS friends and premarital sex. The friends of the youth living in Utah are predominately members of the Church, yet these youth experience considerable sexual pressure from their friends. It is clear that having LDS friends is not the issue as much as having good friends, LDS or otherwise, who strongly value chastity.

To assess the frequency of date rape among LDS youth, we asked whether they had been “forced” to have sex. Five percent of the girls and, surprisingly, 5 percent of the boys replied “yes,” and those numbers increase to 9 percent (boys) and 21 percent (girls) when looking only at high school seniors. We did not define “force” for them; it is clear, however, from their responses to other survey questions and many anecdotal comments that the respondents viewed it as stronger than coaxing or pressure. While most did not think of the experience as actual rape, it was evident they viewed their involvement as being against their will. We were even more shocked by the degree that LDS young men and women reported that they themselves forced someone to engage in sex. The percentages are small (5 percent of boys and 4 percent of girls), but it is still disturbing to see that some LDS young people have forced others into immoral activities.

THE INFLUENCE OF RELIGION Although peers have a powerful influence on sexual behavior, perhaps the most important finding from this study is that other forces have significant effects as well. One important predictor of premarital sexual behavior is religiosity. Figures 1 and 2 show that the religiosity of LDS teens, independent of peer pressures, produced a significant negative influence on sexual activity for both boys and girls. This means that the stronger the religiosity of youth, the less they engage in premarital sex. For example, among boys in Utah Valley, only 5 percent of those who believe in God reported sexual experience, compared to 25 percent of those who don’t believe.

This is a profound finding inasmuch as many social scientists have discounted any impact religion may have in the lives of teenagers. For LDS youth, religion does indeed make a difference. This is great news—encouraging, hopeful news.

Religiosity is a composite of several dimensions—religious beliefs, public religious behavior, personal spirituality, acceptance in local congregations, and family religious practices. Although all of the dimensions of religiosity are related to premarital sex, some have considerably stronger influence than others. In the model, public religious behavior (attendance at Church activities) surfaced as the most important influence in helping youth stay morally strong. Private religious behavior (personal prayer, scripture reading, testimony, etc.) was also important. Although its direct effect on premarital sex was not as strong as other religious dimensions, family religiosity exerted a strong indirect effect through its influence on the other dimensions of religiosity.

THE INFLUENCE OF PORNOGRAPHY Pornography emerged as a statistically significant predictor of premarital sex for young men in the structural equation model. Given the explosion in accessibility of pornography via the Internet, this finding is worrisome. There is awful potential for pornography to lead young men to sexual sin.

Pornography was not a significant predictor of sexual activity for young women. This is welcome news, but it does not mean that young women are not affected by pornography. Little research has been conducted concerning the impact of pornography. It may be that young men who view pornography tend to treat young women as sex objects and become more aggressive in their sexual demands. Thus pornography may influence young men, who in turn influence the sexual behavior of young women. More research is needed in this area. It is clear, however, that pornography contributes to the pollution of our moral environment, and all youth, but particularly young women, are facing increasingly dangerous sexual pressures.

THE INFLUENCE OF FAMILY Some social scientists have argued that by the time children become teenagers, peer influences are primary in their lives and parents have little, if any, influence on the behavior of their children.8 Although family factors did not have a direct impact on premarital sex in our study, mother’s regulation showed a powerful indirect impact. Parents—particularly mothers—can indirectly affect their teens’ sexual behavior by influencing their choice of friends, strengthening their ability to withstand pressure, and enhancing their religiosity.

Of all the family factors we tested (structure, connection, regulation, autonomy), the only one to emerge as significant in the model was mother’s regulation. It is mothers who make the difference, and regulation is most important. In other words, the more a mother sets rules, monitors compliance, and dispenses appropriate discipline, the less her children will be negatively influenced by friends and the stronger their religiosity. These characteristics in turn lower their sexual activity. For young men, a mother’s regulation also reduces exposure to pornography, which lessens the likelihood of premarital sexual activity.

The power of a mother’s regulation is illustrated in young women in the Pacific Northwest, among whom sexual activity was reported by only 7 percent of those whose mothers set rules and monitored compliance. On the other hand, among the girls whose mothers were not involved in regulation, 23 percent had participated in sex.

Even though mother’s regulation was the only family factor to emerge in the model, other family characteristics were also statistically important. In addition to regulation, the other two aspects of the parent-child relationship—connection and autonomy—also produced significant bivariate correlations with sexual behavior.

Connection with parents was significantly related to lower sexual behavior for both boys and girls. Connection—positive emotional bonds of love—signals to youth that their parents care about them; in turn, youth more strongly want to please their parents. Also, effective regulation must be based on strong connection. Interestingly, in the study connection was more important to young women than to young men.

Psychological autonomy was a much stronger predictor of premarital sex for young women than for young men in our study. This type of autonomy does not deal with behavioral freedom, but rather with freedom to think one’s own thoughts and to be one’s own person. Parents withhold psychological autonomy by controlling or manipulating their child’s emotions and opinions; a lack of psychological autonomy often leads to low self-esteem. Previous research has found that low self-esteem is related to higher sexual activity for girls but not for boys.9

Other family factors also produced interesting results. Single-parent families and maternal employment were both indirectly related to increased premarital sexual activity through their effects on the three parenting behaviors (regulation, connection, and autonomy). It appears that in these situations, parental regulation is compromised; the results of this study suggest that parents who find themselves in such circumstances should strive to have greater emotional connection with their children and should make more concerted efforts to be aware of and regulate their children’s activities.

IMPLICATIONS

We have highlighted some disturbing findings from this study, but amidst this gloomy scene, there is hope. Parents and Church leaders can mitigate the negative influences of society and clothe youth with the protective armor of God.

These findings, combined with hundreds of written responses from LDS young people, lead us to three foundational directives for parents and youth leaders: 1) increase the spirituality of the youth, 2) fortify young women, and 3) strengthen family ties. These three things may seem overly simplistic, yet they have proven again and again to be powerful tools in helping youth remain morally clean in a morally corrupt world. We cannot isolate our youth from the world and all its evil influences, but we can indeed insulate them.

Increase Spiritualiy

With regards to premarital sex, public religious behavior has a powerful deterring effect. In previous research, we found that private religiosity and personal spirituality were even more significant. What all this seems to say is that religion makes a difference. Public religious behaviors, such as attendance at church meetings and activities, are important in the spiritual development of our youth. Yet attendance without the fortification that comes with private religious behaviors, such as personal prayer, scripture study, and spiritual experiences, will have less power. Many of the youth themselves recognized the power of religion in their lives and spoke of how it helped them resist moral temptations. “I love being a member of the Church,” one young woman reported. “I have developed a personal testimony of the gospel. I know that I am a daughter of God, and that belief helps me resist temptation.”

When asked, “What has been the strongest influence in your life to live the standards of the Church?” one young man wrote:

My parents and Church leaders have been a good influence. I am very grateful for their strength and belief in the gospel. I believe because of these people, the scriptures, and my own testimony of Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ that I am not personally affected by the negative things I face. I have no desire to do things or participate in things that would bring me shame or damage my spirit.

From scores of similar statements, we can see that, in the home and at church, parents and leaders must create environments where youth can not only learn the truths of the gospel but also feel the Spirit in their lives. We need to lead teenagers to come to know the Lord themselves through sincere, regular personal prayer and scripture reading and similar spirituality-promoting activities. Some of the things we teach and do with our children, like family home evening, are essential, but they are still somewhat external. These teachings and activities are actually a means to an end. The end we seek, and which has real power in the lives of young people, must beinternal—their own testimony and personal guidance by the Spirit. “With all our doing, with all our leading, with all of our teaching,” Church president Gordon B. Hinckley has taught, “the most important thing we can do for those whom we lead is to cultivate in their hearts a living, vital, vibrant testimony and knowledge of the Son of God, Jesus Christ, the Redeemer of the world.”10

With our children being exposed to immoral temptations at younger and younger ages, it is vital that we help them obtain this strong spiritual foundation and personal testimony as early as possible. Parents, teachers, and leaders need to recognize that it is not merely “activity” that we seek in youth, but personal testimonies. Just as all that we do in the home should be focused on this ultimate objective, so too should it be the focus of lessons, activities, and programs at church. “Perhaps we should be less concerned with fun and more with faith,” President Hinckley has counseled youth leaders.11

Fortify Young Women

In our study LDS young women seemed to be far more vulnerable to the influence of peers than young men. They know in their heads that premarital sex is wrong, but when they face their “moments of truth,” too many succumb. Why? In a related study we interviewed 50 unwed teenage mothers in Utah County. We asked them, “Why did you engage in sex the first time?” Their answers stunned us. The most frequent reply was, “I don’t know. It just happened.” Even when pushed for a more informative answer, nearly half of the girls, 48 percent, firmly stuck with the claim that they did not know why they participated in such serious behavior. They were emotionally “paralyzed” when they found themselves in the risky circumstances and were unable to resist. The next most commonly cited reasons for engaging in premarital sexual intercourse were feeling pressured and a desire to feel wanted. These three reasons—”don’t know,””was pressured,” and “to be wanted”—accounted for nearly all of the responses. Only one girl stated that she had engaged in sex because she was “turned on” and had actually wanted to do so.

In a related study we interviewed 50 unwed teenage mothers in Utah County. We asked them, “Why did you engage in sex the first time?” Their answers stunned us. The most frequent reply was, “I don’t know. It just happened.” Even when pushed for a more informative answer, nearly half of the girls, 48 percent, firmly stuck with the claim that they did not know why they participated in such serious behavior. They were emotionally “paralyzed” when they found themselves in the risky circumstances and were unable to resist. The next most commonly cited reasons for engaging in premarital sexual intercourse were feeling pressured and a desire to feel wanted. These three reasons—”don’t know,””was pressured,” and “to be wanted”—accounted for nearly all of the responses. Only one girl stated that she had engaged in sex because she was “turned on” and had actually wanted to do so.

These troubling results are not new. Our experience, both as researchers and as Church leaders, has taught us that most young women in the Church who become sexually active do so for nonsexual reasons. In the words of an unwed mother, “I liked being with someone. I like getting attention from guys.”

Another said: “The feeling of having a man or a relationship and not wanting him to leave me is what made me have sex. I thought that giving him some sort of sexual pleasure would make him like me more and stay around longer.”

Most of these girls were initiated into sex before age 16. It is somewhat surprising that they would have desires for male acceptance at such a young age. These young women, like so many others both in and out of the Church, confuse sex with affection and belonging. They engage in behaviors they know to be wrong not because of passion but because they are desperate for confirmation that they are attractive and acceptable or because they feel some obligation to please.

In the book Reviving Ophelia, Mary Pipher discusses the painful identity crisis that many young women in the United States experience as they enter adolescence. She reported that many of the girls she counsels in her practice engage in sex because they “didn’t know they had the right to make conscious decisions about sex” and they “didn’t know how to say no” or because they “desperately wanted acceptance and would do anything, including having sex with virtual strangers, to win approval.”12

What, then, can we do to help our young women? What can be done to fortify them as they encounter the culture of sex and the pressure to please others? In addition to strengthening their spirituality, we can lead them to discover their self-worth, independent of a boyfriend, physical appearance, or popularity. We can teach them that true affection and acceptance are not related to premarital sex; in fact, sexual immorality destroys meaningful relationships.

We can teach them that they have no obligation to please another or to “be nice” if it means doing something immoral. Sometimes young women feel that having someone mad at them for saying no is a sin worse than immorality. We can help them understand that self-acceptance and approbation from God are far more desirable than the false validation that comes from casual sex. Saying no and really meaning it is evidence of personal power and self-confidence as well as an expression of integrity and virtue.

We can also teach young women to avoid people, places, and circumstances where they may not have control or may lack room to navigate around the temptations they encounter. To do this parents must be more cognizant of what is going on in the lives of their daughters.

In addition to helping young women better understand their divine nature, parents and leaders can fortify young women by teaching these same principles to young men. We can better protect girls as we teach boys how to honor, respect, and properly treat women. We should teach LDS young men to stand up for LDS young women and to protect them from sexual dangers. They can privately warn a young woman that the attention she is receiving is from a young man with evil intentions. Having male friends who might be characterized as protectors would particularly benefit young women in the Church.

“Band together and strengthen one another,” President Hinckley has counseled youth of the Church. “And when the time of temptation comes, you have someone to lean on, someone to bless you and give you strength when you need it.”13

Strengthen Family Ties

Family plays an important role in whether LDS teens become sexually active. The results from our study were very clear—parental regulation is vital. “Regulation” does not imply hidden cameras or private investigators. Rather, appropriate regulation involves parents and children agreeing on rules concerning, among other things, curfews, use of the family car, and association with members of the opposite sex. Rule setting is more effective if teens have some degree of ownership in the process. As one teen stated, “It is pretty hard to rebel against family rules when you helped set them.” Young people need the structure of such rules in their lives.

Effective regulation requires parents to be aware of what is going on in their children’s lives—to know with whom they associate and in what activities they participate. Parents need to spend time with their children and demonstrate loving concern. “My parents always want to know where I am going,” one young man reported. “Every night before I go to bed, I check in with my parents. They talk to me about my life and any concerns I may have. We talk a lot, and as a result they always know what’s going on in my life.”

Contrary to our expectations, the vast majority of the youth in our study praised appropriate discipline from their parents, and many actually wished for more. One young woman stated, “Sometimes I wish my parents were stricter. I wish they were more like parents and less like my buddies. Sometimes I just need someone to put their foot down and say, ‘This is the way it’s got to be.'”

Adolescents more readily accept discipline if it is administered consistently and fairly, never arbitrarily. Many youth made comments like this one: “My parents should stick to their punishment. They always let me off the hook early. I think it would be more effective if they wouldn’t do that.”

Youth are smart enough to understand that regulation, including discipline, is in large part a function of parents’ love for them. “I often felt I was not cared about because I was never punished for anything,” one student remembered. “I was given no rules or chores. I felt like my parents didn’t care what I did, which in many cases they didn’t. They were too wrapped up in their own lives.”

Most of all, regulation and discipline will have greater power in the lives of our children if they feel emotionally connected to us. They want to feel loved, supported, praised, accepted, and important. Every expression of love for our children, whether in word or deed, not only builds family connections, but also strengthens the power of regulation.

Psychological autonomy is vital for young people. When teens are denied this freedom at home, when they feel their parents do not respect them as individuals, they turn to others for direction and acceptance. Denying psychological autonomy reduces parental influence and gives peers inordinate power. The more we help teens to attain a healthy sense of emotional or psychological competence—the more we respect their feelings, the more we lovingly guide them as they explore their thoughts and ideas—the greater will be our influence. The more we control or manipulate our children’s thoughts and emotions, whether unwittingly or purposely, the less we will influence them in the long run.

Cultivating these three parent-child relationships—regulation, connection, and psychological autonomy—will yield rich dividends in helping youth not only to resist temptation but also to apply gospel principles in their lives.

At times, raising teenagers in these difficult days may seem to be an impossible task. We can take hope, however, in the fact that there is protective power in genuine gospel living. As we live the gospel and help our children do the same, we will experience a very real “refuge from the storm” (D&C 115:6). That refuge is not so much a geographical place as it is a spiritual condition. We can—we must—help our children achieve that condition and be the “youth of the noble birthright.”14 This is our sobering, yet sacred, responsibility as parents and leaders of youth. It is daunting, but it can de done—with the Lord’s help.

NOTES

1. Cited in a talk by Brigham Young, April 25, 1860; Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), vol. 8, p. 55.

2. Boyd K. Packer, The Things of the Soul (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1996), p. 110.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Youth 2001 Online, Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (https://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/yrbss).

4. Joyce C. Abma and Freya L. Sonenstein, Sexual Activity and Contraceptive Practices Among Teenagers in the United States, 1988 and 1995, National Center for Health Statistics, Vital and Health Statistics, series 23, no. 21, p. 29.

5. Alan Guttmacher Institute, “Teenagers’ Sexual and Reproductive Health: Developed Countries,” Facts in Brief, 2002.

6. Abma and Sonenstein, p. 29.

7. Rodney Stark, “Religion and Conformity: Reaffirming a Sociology of Religion,” Sociological Analysis, 1984, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 273–81; and Rodney Stark, “Religion as Context: Hellfire and Delinquency One More Time,” Sociology of Religion, 1996, vol. 57, pp. 163–73.

8. See Judith Rich Harris, The Nurture Assumption (New York: The Free Press, 1998).

9. Les B. Whitbeck, Kevin A. Yoder, Dan R. Hoyt, and Rand D. Conger, “Early Adolescent Sexual Activity: A Developmental Study,” Journal of Marriage and the Family, 1999, vol. 61, pp. 934–46.

10. Gordon B. Hinckley, Teachings of Gordon B. Hinckley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1997), p. 648.

11. Ibid., pp. 712–13.

12. Mary Pipher, Reviving Ophelia (New York: Ballantine Books, 1994), pp. 209–10.

13. Hinckley, p. 429.

14. “Carry On,” Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 255.

Brent Top is a BYU professor of Church history and doctrine, and Bruce Chadwick is a BYU professor of sociology. Matt Evans is a sociology doctoral student at BYU. This article is an outgrowth of a previous study by Top and Chadwick on teen delinquency, published in Brigham Young Magazine in 1998 as “Raising Righteous Children in a Wicked World.”

Download an Adobe Acrobat PDF version of “Protecting Purity.”

This document is in Adobe Acrobat format. If you do not already have a copy of the Adobe Acrobat Reader, it is free and can be downloaded athttps://www.adobe.com/prodindex/acrobat/readstep.html![]()

Related Article: “Raising Righteous Children in a Wicked World.”

FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.