By Giles H. Florence Jr.

KBYU has produced a mini-series about family history called “Ancestors.” It will air next January nationwide and will run for ten weeks.

Garry Bryant served in the United States Air Force during the Vietnam War for only one reason. The U.S. Air Force would completely pay for his college education. Unable to feel any patriotism as a soldier, Garry spent much of his time in the service depressed about having enlisted. An insight came to him later that would completely change his views and his values. “Had I known then what I know now about how rich my military heritage is,” he recalls, “I would have been a different soldier.”

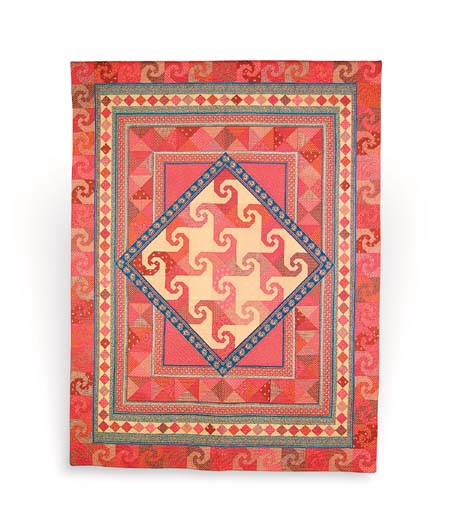

The creative and beautiful hand-sewn quilts left by her grandmother, inspired Nancilu Burdick to want to write the story of that artistic ancestor’s quilts and her life. “But until I was in bed after an accident and began to explore quilting with my own hands, I had been unable to actually write Grandma’s story. It was as if I had to be working in her art to be able to write the story well. As I worked, Grandma seemed to be saying to me, ‘Yes, please tell my story.'”

When Victor Villaseñor grew up in Southern California, he was made to feel excluded and judged for being Mexican-American. “You a Mexican?” his little red-headed friend, Howard, asked in first grade.

“Yeah,” Victor answered.

“You got a knife?” the friend began to raise his voice.

“No.”

“Yeah! All Mexicans got knives. You got a knife.”

Victor’s response was one of innocent surprise. “I didn’t know, hey. Honest, I didn’t. I’ll bring one tomorrow.”

“No, you got one and I can’t play with you. Mexicans are bad people.”

“I didn’t know, man. Really!” was all he could think to say.

As he grew up alienated because of his heritage, Victor’s questioning heart led him to search his past for answers, and the journey he took through the branches of his family tree brought him a feeling of wholeness and worth.

These glimpses into three personal experiences reveal a quiet power that is sweeping the world as millions are being healed and are discovering meaning in their own lives by connecting with their extended family, often changing how they see life and what really matters to them. An unprecedented surge of interest in family history is being driven by widely diverse factors. One is the decline of the extended family, in which two or three generations often would live together. It is rare these days to see more than what we call the nuclear family with even parts of generations living in the same city, let alone in the same home.

In today’s nuclear family of father, mother, and children, the atom appears to have split and the nucleus less visible than ever. Besides broken homes, the drive for connectedness gets attributed to the alienation that often accompanies technology. Television has replaced evening story-telling by parents or grandparents, and children know more about the lives of the uncles and aunts in sitcoms than in their own family. Fractured families have produced sorrow, confusion, and regrets, but they have also produced many people seeking to be reconnected to something. They don’t always know what.

The genealogy craze may seem surprising to Latter-day Saints. When family history or genealogy classes or workshops are offered in church, overcrowding is rarely a problem. Genealogy has often been seen as the domain of the elderly, retired, or sedentary, sometimes a curiosity about relatives on the Mayflower or to qualify as a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Not any more. Genealogy is among the fastest growing hobbies in the world. Ever since Roots, Alex Haley’s phenomenal docudrama about his own ancestry, was televised in the late 1970s, seeds of interest in genealogy have germinated widely. Cultivators and root-seekers by the millions are vigorously tending the forests of family trees that suddenly sprang into consciousness. The trees were there all the time, of course, but they now buzz with the activity of people climbing them, pruning them, and plucking their fruit.

To Latter-day Saints the most precious fruit of genealogy has always been the sealing of generations to create eternal families. For the secular genealogist, the most delicious fruit on family trees can be tasted right now, here, in this life. It is the pleasant surprise that hidden in the family tree are vital secrets that often bring significance to the life of the seeker.

After serving in the Air Force, Garry Bryant found himself back home searching through his own family records. The search may have been prompted by a discussion in the barracks one night when Garry was feeling cynical as other soldiers discussed their heritage–some of whom had descended from veterans of the Revolutionary War. “I remember thinking that my ancestors had probably all come to America after its independence, but I was in for a surprise. I discovered how wrong I was. My family had a rich military history, with at least 10 men who fought in the Revolutionary War.

“The story that affected me most, both emotionally and spiritually, was the life of Pvt. John Straughan, one of George Washington’s special troops, called Morgan’s Riflemen. They defeated the British in the Battle of Saratoga, then marched south to assist in other battles, trudging through snow leaving bloody prints, since many had no boots.

“I think back on myself as a young airman in the barracks ignorant of this patriotic legacy, and I’m ashamed,” explains Bryant. “When I was a soldier, I didn’t know or care about what John Straughan and men like him had done for me. Had my family preserved that history and shared it, I think I would have been a different soldier.”

A newly respectful Garry Bryant wrote three volumes of his family’s history, then had another flash of insight. “With the books complete, I felt a disappointment, realizing they would be put on shelves to gather dust. It seemed so anticlimactic. Then it came to me that the next step I needed to take was to incorporate that heritage into my own life and my family’s. That’s when I began my love affair with my Celtic heritage–blending past, present, and future.”

Garry’s involvement in several Scottish organizations found him participating in events, celebrations, and service projects. “All of which prepared me to face a debilitating stroke that would have been harder to get through without knowing about the great obstacles my ancestors had overcome.” Garry Bryant attributes his renewed appreciation for life to an awareness of his ancestors, his heritage.

Garry is one of more than 100 million Americans who have begun to rustle the leaves of their family trees as they seek their own identity through their forebears. Like Garry, both Nancilu Burdick and Victor Villaseñor discovered treasures in their own family histories that gave each of them new direction, energy, and joy in their lives. They will all three be featured in a 10-part television series produced for PBS by (who else?) KBYU-TV. Part documentary and part how-to, Ancestors is scheduled for national release in January of 1997. Using richly diverse stories of real people, the program portrays how lives are affected when individuals make connections with their ancestors in one way or another. In the tradition of other finely-crafted documentaries like Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation, and Ken Burns’s The Civil War and The West, this new series brings history to the personal level–through the eyes of ordinary, everyday people–and makes it entertaining.

To the average TV-watching Latter-day Saint in America, it may seem obvious that if a series should ever be done about genealogy, KBYU, which is owned and operated by BYU, would be the obvious station to produce such a program. Indeed, KBYU has presented genealogy programming, as have other Church production groups. But most of these were directed toward LDS audiences. KBYU has never undertaken a program of this scale directed at a national audience, one that might be indifferent to or even critical of the religious aspects of genealogical research.

The idea of the program began more than 10 years ago when BYU graduates Tom Lefler and John Earle discussed the possibility of filming a portrait of genealogy that might be produced for a national audience, in a form that would appeal to that eternal dimension of the human family. (At the time, Lefler was working for BYU’s Motion Picture Studios and Earle was with the Utah State Film Commission.)

“We knew it couldn’t contain any religious indoctrination,” recalls Lefler, who ultimately became the executive producer of Ancestors. “It made sense to us to leave religion out and to reach out to that universal longing for immortality in mankind, even if it may be dormant.”

Interest in sharing the genealogy message to a national audience also occurred to KBYU project managers Babette Davidson and Diena Simmons at about this time. The latter had worked with PBS on some programs and was aware that “how-to” programs drew public television’s largest view ing audiences. Eventually, the idea of collaborating on a potential project brought Simmons and Lefler together, seeking a clearer vision and some way to fund it. Since it was a big vision for a small station, inexperienced in national programs with million-dollar budgets, they felt they needed someone involved who could bring credibility to their plea for funding. Both Lefler and Simmons had known film producer Sterling VanWagenen, whose motion picture Trip to Bountiful won an Academy Award. Himself a BYU graduate with commercial success behind him, he was seen as having the credibility that would help them raise both the financial backing and Church-university approval to undertake the grand project they envisioned.

Interest in sharing the genealogy message to a national audience also occurred to KBYU project managers Babette Davidson and Diena Simmons at about this time. The latter had worked with PBS on some programs and was aware that “how-to” programs drew public television’s largest view ing audiences. Eventually, the idea of collaborating on a potential project brought Simmons and Lefler together, seeking a clearer vision and some way to fund it. Since it was a big vision for a small station, inexperienced in national programs with million-dollar budgets, they felt they needed someone involved who could bring credibility to their plea for funding. Both Lefler and Simmons had known film producer Sterling VanWagenen, whose motion picture Trip to Bountiful won an Academy Award. Himself a BYU graduate with commercial success behind him, he was seen as having the credibility that would help them raise both the financial backing and Church-university approval to undertake the grand project they envisioned.

Lefler, Simmons, VanWagenen, together with writers and producers Marcy Brown and Stephanie Ririe and head researcher Jane Wilson, soon undertook a mission that they refer to as a five-year obsession, gathering interest and other talented people at every turn. The university was supportive but cautious, a significant amount of funding pledged by private sources fell through, and PBS was keenly interested but content for someone else to pick up most of the tab. Gradually, though, the Ancestors project gained the status of a production that would eventually see the light of the cathode ray and be broadcast to the nation.

“Support began coming from so many directions,” Simmons vividly remembers. “But there were delays at every possible turn. We could see the potential good that such a program could have, and the obstacles kept testing our commitment to it. Alex Haley was asked to host the series and had agreed to that, but he died unexpectedly just after making that commitment. Our first source of money didn’t come through, and unforeseen barriers popped up everywhere. Still, beneath it all, we felt a guiding hand leading us forward. It has been the most extraordinary project I’ve ever worked on for that reason.”

All participants agree that the delays in producing Ancestors have actually allowed technology to become even more helpful to genealogists, with CD-ROM capability now in homes, homepages on the World Wide Web in place, and instant film imaging being affordable, to name a few.

With strong university support and assistance from the LDS Motion Picture Studio–and combining VanWagenen’s contacts in the film industry with Simmons’s work with PBS–the means became available to produce Ancestors. The BYU Film Committee and Division of Continuing Education committed substantial resources to the project, and Eastman Kodak took an interest in sponsoring the show, because its image processing systems are important tools for genealogists in enhancing and copying photographic images. Brøderbund, the software manufacturers that designed Family Tree Maker (a computer program for genealogists), also became a sponsor, contributing funds and resources to the production. Eastman Kodak and Brøderbund were then joined by Ancestry, the publishers of print and electronic materials for family historians; AGLL, the largest private distributor of genealogical materials in the nation; Lineages, a genealogical research service; Palladium Interactive, producers of family history products for computers; and The George S. and Dolores Doré Eccles Foundation.

Under the direction of KBYU’s former general managers, Thomas A. Griffiths and R. Mel Rogers, and their successor, John Reim, support continued to solidify, despite the difficulties of a project of this size. Coincidentally, the president of PBS during much of this time was Bruce Christensen, a member of the Church who felt the need to remain neutral about the project at PBS, even though he was supportive. His staff also favored running the program and allotted certain funds to get it under way.

Two years ago, Christensen was appointed dean of the College of Fine Arts and Communications at BYU and has supported the project from this side of the table. “Once the proposal was right,” he said, “things began to happen, and it just went.”

When Alex Haley died of a heart attack, the need for a new host raised important questions. Was having a celebrity really the best way to get attention for the show? Or would a known personality draw viewers’ attention away from the main point of the program? As unfortunate as Mr. Haley’s death was, what at first appeared to be a setback led to an unlikely twist. Lefler and VanWagenen met amateur genealogists named Jim and Terry Willard in New England at a genealogical society seminar, where this husband and wife team were demonstrating computer methods for family history.

“I realized instantly that Jim had all the qualities we were looking for in a host, except name recognition,” VanWagenen explains. Jim and Terry are retired school teachers who had been bitten by the genealogy bug and never recovered. After 30 years of avid pursuit of their hobby, the Willards have acquired the knowledge and experience of professional genealogists and yet still maintain the genuine, child-like fascination and enthusiasm of the novice. This rich combination suits them perfectly for the role of co-hosts of Ancestors.In that role they introduce and moderate each episode with the homey style of a “Mr. (and Mrs.) Rogers”–from their simple, smiling sincerity, to the untrained way Jim reads the teleprompter, to their spontaneous manner of questioning their guest experts (as if they’re actually listening to what the guest is saying rather than eager to get on to the next question they had in mind). Something refreshing comes from the slightly nervous genuineness that Jim and Terry bring to television, where so much seems over-rehearsed and so professionally smooth as to be artificial.

As hosts of a nationally televised mini-series, the Willards themselves represent the ironies of the subject they are presenting. They are not famous. They are not professional genealogists. They are not Latter-day Saints or BYU graduates. Yet they seem right for the part they play. Likewise, genealogy is a sleeper of a subject–not recognized for having the kind of interest and attention it is getting. Curiously, new technology is reviving the old art forms and older simpler values that genealogy entails. We often attribute new technology with alienation. Yet those who are using the technology to turn to family history are being healed of alienation. They express a delight at feeling connected to their roots.

Even those who don’t use computers say that working in the past has significance in the present, that working among the dead makes living a richer experience. One would expect that the efficiency of a computer keyboard and screen might seem clinically cold compared with the tactile experience of yellowed paper records, musty old archives, attics full of treasures, and the nostalgic experience of searching through cemeteries and doing rubbings on gravestones. But the searchers describe robust emotional experiences right at the computer terminal in libraries around the world.

Ancestors deals well with both the art and science of family history–displaying well its scientific requirements of precision and accuracy, its use of numbers and columns, charts and lists, its demand for information in proper places entered in proper ways–all contrasted by its artfully warm and moving stories, as well as the connection of meaningful relationships that charge people’s lives with importance.

In one segment, Nancilu Burdick tells of being “commanded” by her aunt Molly Ruth to write the story of Grandma Talula Bottoms, whose quilts were works of art. “The quilts had been stored in an old cedar chest,” Burdick tells us, “so beautiful . . . it was as if I’d found a treasure. The desire to tell her story lay on me like a burden at first, then became a challenge, then a joy. I tried to write about her work but until I was ill and had to spend weeks in bed, I had never quilted, myself. Once I had gone through the process of piecing those patches together, I began to feel her presence. I could almost hear her say to me, ‘Yes, dear, tell my story to my great-grandchildren.’ And once that happened, I was able to begin the writing.”

By piecing together the present and the past, Nancilu undertook to emulate her grandmother. Quilts really are patches of family history sewn together in patterns and designs, sometimes even patterns or pictures that represent stories or events. Quite often the fabric of the patches had been cut up from old clothing they wore, tablecloths they ate on, or curtains they opened and closed daily. The clichéd metaphor of the patchwork quilt takes on new significance in family history, as the twin processes cause us to join small pieces of one life with pieces of our own to make a new whole. Past lives take on a new presence, old events have new meaning, memories live in a fresh context.

As Ancestors was being produced, the early stories had been collected in random ways. What executive producer VanWagenen found was that “some weren’t even stories at all, just fragments. No single strategy had guided the collection. I felt we needed a set of guidelines to gather the data, something that would bring discipline to the format. We needed a frame.

“It was clear that ‘how-to’ programs were growing in popularity. People do enjoy learning new things. It was obvious that the baby boom generation values family and is interested in reconnecting with its roots. It was also clear that those of us working on the production had limited genealogy experience. Since we wanted to do it right, we went to the Family History Department of the Church for instruction.

“Our team of writers, researchers, and producers were taught in the science of gathering family history and genealogy. We learned to question consistently and thoroughly each source, maintaining the point of view for each story so that no matter which stories we ended up using, we had as much information as would be needed.

“We assembled a national advisory group of historians and professional genealogists to help us maintain the highest standards of both the art and science of gathering family history. What we were trying to do was to translate something that has spiritual as well as emotional significance to us into a presentation that would appeal to common interests of people everywhere. We hoped to make genealogy look easy to do right from the start, and we wanted the fun and pleasure of the process to be obvious.”

To do this, each of the 10 episodes are broken into two segments, each segment designed to be brief enough to leave the viewer wanting more. The Willards introduce the topic of the individual episode, such as: getting started, gathering stories, using libraries and archives, making sense of military records and censuses. The first segment always focuses on an individual telling his or her own story: inmates in prison doing genealogy on computers, a Scots-American family that has held reunions since 1889 and filmed them since 1915, Chinese-Peruvian immigrants to the United States who help their daughter come to terms with confusion about her heritage. These cameo portraits of lives changed by family history in some way all demonstrate the nobility in even lives that seemed most common. In the second segment of each episode, the hosts interview an expert in one of the topics. In the interviews, the Willards show their skill as master teachers. Their enthusiasm and curiosity are infectious and will engage viewers at every level of interest.

The Willards’ own story, though not included in Ancestors, enables them to share background experience with any guest. Jim and Terry met in high school near Augusta, Maine, where she had been raised in a French-speaking home. “I knew I was different,” she says, with her ever-present smile. “I always thought it was neat my family continued the language and culture.” She majored in French at the University of Maine. Jim attended Boston University and then graduated from the University of Maine in history.

When they married in 1969, they wanted a hobby they could share and chose genealogy. In the years since, Terry has traced her lineage back 14 generations on both sides and Jim has traced both his maternal and paternal lines back 12 generations. Since both were teachers, they spent many summer vacations traveling through rural Quebec, from village to village, talking with anyone willing to share oral histories of the area. They learned how their own forebears had fought on opposite sides during the French and Indian War, how they marked their sheep in the early days, what medicines they took, and how they spent their lives. “Genealogy to me,” Terry explains, “is not just doing paper work. It’s meeting people and sharing stories. Maybe none of my ancestors are famous, but I find myself having a renewed appreciation for the ones who left a civilized place like France to come to an uncivilized one. My ancestor who bore eight children and worked beside her husband in the fields, pulling a plough–she’s a hero to me.”

Jim adds, “The great thing about genealogy is it takes as much or as little time as you can give it. You can always walk away from it and pick it up later. I mean, your ancestors aren’t going anywhere.”

In Episode 5, the Willards host a tour of the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, pointing out that the facility houses records on more than 2 billion people, all on 1.9 million rolls of microfilm. They browse among the 270,000 volumes of compiled family histories. (To give some idea of size, the oldest and largest genealogical society is the New England Genealogical Society in Boston, containing 150,000 volumes, some 10,000 rolls of microfilm, serving 17,000 members.)

In Episode 5, the Willards host a tour of the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, pointing out that the facility houses records on more than 2 billion people, all on 1.9 million rolls of microfilm. They browse among the 270,000 volumes of compiled family histories. (To give some idea of size, the oldest and largest genealogical society is the New England Genealogical Society in Boston, containing 150,000 volumes, some 10,000 rolls of microfilm, serving 17,000 members.)

“The job of the genealogist,” explains genealogist Rafael Guber, “is to take the records that have turned people into numbers and give them back their names, in fact, more than names, their identities.”

America has often been called a melting pot because of the vast range of cultural mix here. We have blended more ethnic cultures into one pluralistic society than any nation in the history of the world. But a more appropriate term than melting pot for today’s America is tossed salad. The difference being that in the melting pot, like a great stew, the flavors are so blended that each contributes to the other until they all share a co-mingled taste. The distinctness of each has been surrendered in the whole. By contrast, a tossed salad is a combination of flavors in which each vegetable maintains its own taste.

Americans today like to celebrate their differences, and each culture has worked to regain its own identity after centuries of being assimilated into a melting pot. In one episode, Guber describes the ethnic blending going on in this country until people forgot their individual heritage. “We were so busy,” he laments, “stuffing ourselves on the bounty of this country that we lost our distinct identity and personal contact with our own people.” Another important source of genealogical information for Americans comes from Ellis Island, where manifests from the ships and immigration files were kept for many years. The passenger lists of arrivals contain valuable information. As many as 30 columns on the manifest record where the passenger came from, when, how much money was in his pocket when he arrived, who had paid for his passage, where he would stay in America, whether he could read, and a brief physical description. For this episode, Rafael’s family dressed in period costumes and re-enacted their ancestors’ arrival at Ellis Island, in an attempt to more fully appreciate what it must have felt like to come to this country and leave theirs behind.

Whether we agree to refer to our ethnic mix in this country as a melting pot or a tossed salad doesn’t matter as much as that we accept and appreciate our differences. As a first grader, Victor felt great pain at hearing his little red-headed friend, Howard, tell him he couldn’t play with him because Mexicans are bad people. “It hurt then, and after 40 years it still hurts,” Victor admits. “But what I felt as a child was that my parents had lied to me. I wondered if my people actually were inferior.”

Sadly, the isolation and pain didn’t end with first grade. As Victor Villaseñor grew up, he gained the peace and a sense of dignity that can be derived from learning of his own heritage. “Unfortunately, I had carried that resentment for my parents and their betrayal until I was 19. I went to Mexico and began to see who I had descended from, that I had descended from someone. That I was someone.

“Our hope for the present and for the future comes from the past,” says Victor. “The more I learned about my own family, the more compelled I was to write the story, to interpret it for myself. The stories I learned are like million-dollar treasures. And I can say that my greatest heroes now are my parents. Once I came to know of their intimate struggles, I loved and admired them more than I ever knew how before.”

Victor tells the story of his father as a boy, when his father’s family was fleeing the scene of the Mexican Revolution. They went North on a train. His father and other boys saw this as a great adventure and some would dare each other to see who could stand on the station platform longest each time the train stopped. They would wait until it started to roll, attempting to show how brave they were, then run and jump aboard. At one stop Victor’s father waited long enough that he couldn’t make it. The train left without him. With no family and no place else to go, he began to run after the train as it gained speed.

“My father kept running, screaming, ‘Mama, Mama. Don’t leave me.’ Terrified at being left behind he ran that whole day and into the night. Finally, after dark he caught up with the train because it had broken down. We went back there and measured the distance. That little guy, my father, ran more than a hundred miles. When you have love pulling you and fear pushing you, you can do amazing things. What pride and confidence that story gave me. It meant that if my Dad could do that, I could do hard things, things that seem impossible.

“For the next 10 years I wrote and submitted my book to publishers and got 265 rejections. But I couldn’t give up. When you write about people who don’t give up, how do you give up? My father’s story gave me energy that filled my brain and my heart with hope and confidence.

“Once you get inside your family story, an ordinary story becomes a great, great, wonderful story. See, everyone really is special. We’ve all heard that cliché, but the details of our lives tell us so much. When I see the mistakes they made in their decisions, for example, I am now much more able to forgive myself for my own mistakes, not be so hard on myself. There is immense value in the stories of our families; the message is one of great hope.” Families are where we share love, hope, and forgiveness.

The buzzword today in social commentary and political rhetoric is family. Everyone knows it is important. Does it take a village or a family to raise a child? So much is said and argued over, yet so little is done to strengthen the condition of families in America. When Ancestors is televised in the next few months, it will share important information about how easy and fun genealogy and family history can be. Perhaps as important as any practical advice Ancestors offers is its simple wisdom that within the stories of our ancestors there is healing, strength, and hope. Maybe there is no program or assistance or therapy that can give us a better sense of our own worth, our own place, or our own promise, than the honest, plainly told stories of those who have gone this way before us.

Giles H. Florence Jr., ’70, is a freelance writer living in Salt Lake City, Utah.