A good book in hand can foster a milieu of eternal progression.

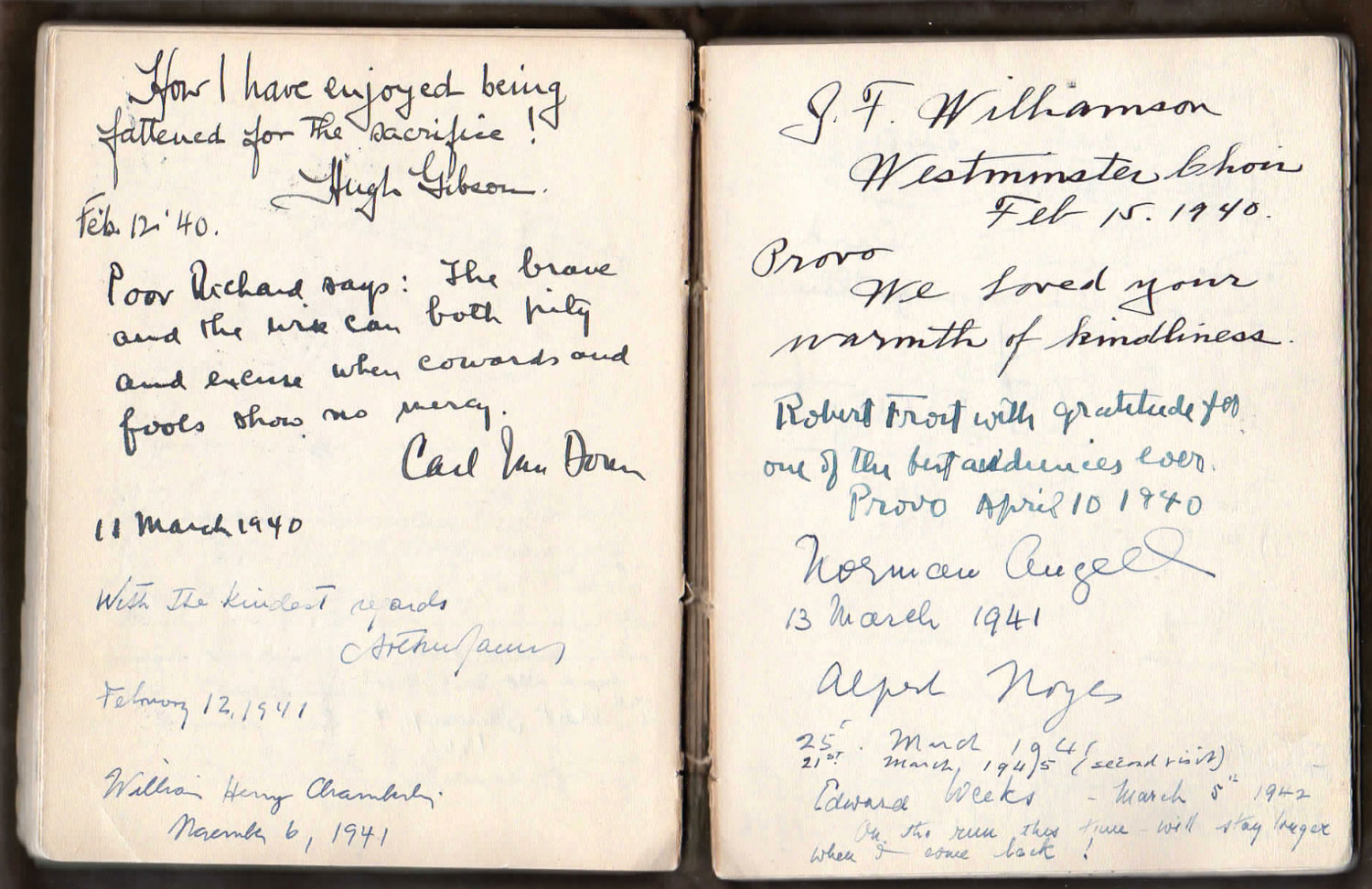

Richard Cracroft reads 30 to 90 minutes every night. His long-suffering wife, Janice, confesses that she hasn’t had a good night’s sleep in a darkened room in 52 years.

Note: To bid adieu to BYU Magazine’s longtime book reviewer, here is an updated version of the 1984 essay that first brought the Cracroftian voice to these pages.

I was certain it was forbidden. And so, of course, I did it—and got away with it, I thought. Night after delicious night, beginning at about age 13, I would say my prayers, prop my antiallergenic pillows high, turn on the bedlamp, and settle in for my nightly read—in such pasty jewels as Tom Swift, Nancy Drew, and, gem of gems, Red Randall at Pearl Harbor. At or near 10 o’clock, my be-nightgowned mother would enter my room; bestow a be-Mentholatumed, be-curlered, and be–cold creamed kiss upon my brow; and turn out my light. As soon as the door closed, I would pull my four-battery Boy Scout flashlight from beneath the mattress and settle in for the most delicious (because forbidden) minutes of my day—reading until the end of the chapter or the episode or the mystery, or until the stack of peanut butter–laden saltine crackers in my bedstand drawer had finally disappeared, leaving their miserable crumbs across the expanse of my bed.

This pleasant routine grew less exciting, however, when I realized, at about age 14, that no batteries could last that long—that Mom had been replenishing them, thus subsidizing my sin. I soon brazenly began leaving the bedlamp on until Dad, elbowed by Mom, would speak as one having authority—that is, loudly—and, after half-past 12 or so, would yell, “Dick, turn out the light—now!” Resigned to the inevitability of sleep, I would grudgingly mumble, “As soon as I reach a stopping place,” and comply.

Since those halcyon days, and especially since becoming a parent myself, I have often pondered the subtle and less-than-subtle ways in which my parents encouraged reading and a love for the arts in our home. I admired them for their conscious and unconscious encouragement, and I wished to go and do likewise. Somewhere, in their very English homes or in high school, they had learned to place a premium on the value of literature. Somewhere, they had learned that literature—and its fair handmaidens, art and music—provides various but satisfying pathways to the discovery of oneself; that study of the best literature (the belles lettres) and the best of music and art allows access to significant human experience and thus can dramatically increase one’s awareness not only of the distinctively human but also the distinctively godlike potential in all of us.

Somewhere, my parents learned that great art, understood in the context of the plan of God, can become a means to awaken, refine, enrich, and sensitize the spiritual man and woman, moving them to joy in recognizing the beauty and truth discernible even in the mists of mortality. My parents learned, and somehow taught their children to respect, the importance of literature in quickening one’s understanding of honor, pity, pride, compassion, courage, devotion, and love—those old values and verities.

When I was ill (which I often was), I could count on Dad’s visit to the public library on my behalf, returning home with stacks of books. When I was about 8 years old, my father took me to the bank, where he opened my own account, taught me how to deposit and save my earnings, and how to calculate my tithing. Then he took me to the majestic library, where I became a card-carrying patron and began, increasingly, to wander the aisles and check out books for two weeks, which I have done ever since.

When I was ill (which I often was), I could count on Dad’s visit to the public library on my behalf, returning home with stacks of books. When I was about 8 years old, my father took me to the bank, where he opened my own account, taught me how to deposit and save my earnings, and how to calculate my tithing. Then he took me to the majestic library, where I became a card-carrying patron and began, increasingly, to wander the aisles and check out books for two weeks, which I have done ever since.

Soon after this, Dad introduced me to his many boyhood volumes of Horatio Alger, The Motor Boys, and Tom Swift, from which I imbibed the old-fashioned values of personal integrity, logical thinking, democracy, fair play, pluck, and the inevitable triumph of good over evil. From my married sister’s abandoned volumes of Nancy Drew, I learned that girls were smart after all and capable of solving all manner of crimes. From such oft-read and reverenced books as Touchdown to Victory, A Minute to Play, All-American, and Ros Hackney, Halfback, I learned gridiron grit, prowess, moral courage, and, despite occasional losses, the inevitable triumph of good over evil. In fact, I secretly became Ros Hackney and imaginatively relived his gridiron successes on our neighborhood sandlot.

When Mom and Dad took me to see Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac, starring Jos� Ferrer, I became an English major in the making, so enchanted that Mom rushed to purchase a copy of the play for me. I devoured it, memorized most of Cyrano’s speeches, and plunged into a summer of front porch dramatic presentations of the play, highlighted by prolonged duels fought with my buddies while we recited Cyrano’s impromptu poetry, which yet rings in my mind: “Hark, how the steel rings musical!/Mark how my point floats, light as the foam,/Ready to drive you back to the wall,/Then, as I end the refrain, thrust home!”

I am grateful for the milieu that my parents established for me, the youngest of my family; from this came my lifelong love of literature and the arts and promoted my love of the gospel. During my 30-month Swiss-Austrian mission Mother stayed on duty, sending me 35 books (which I listed in my journal and still own) by prophets and apostles. I took those books into my soul—they’re still there.

Your customized milieus and those of your children will be different from mine. My mother and father enriched and guided my life through their love, encouragement, and understanding of my needs, and they established a pattern of learning that continues to bless my life. I encourage each of you to establish a milieu adapted to the particular needs of your family—if you haven’t done so already—which will enable your family’s eternal progression.

Your customized milieus and those of your children will be different from mine. My mother and father enriched and guided my life through their love, encouragement, and understanding of my needs, and they established a pattern of learning that continues to bless my life. I encourage each of you to establish a milieu adapted to the particular needs of your family—if you haven’t done so already—which will enable your family’s eternal progression.

Today, at age 75, I am still reading two or three books a week. I have read every night, for 30 to 90 minutes, in every place I have ever slept, over my entire life. Reading is as much a part of my regimen as brushing my teeth, praying, and kissing my long-suffering wife, Janice, a devoted reader herself, who drops off long before I do. She confesses to anyone who will commiserate that she hasn’t had a good night’s sleep in a darkened room in 52 years.

For 20 years this column has always been about books well written and well read, about quality reading that educates, refines, inspires, and blesses readers during their mortal and eternal lives. As I bid a heartfelt auf Wiedersehen to my little flock of faithful and occasional readers, I would like to express how vital it is for ourselves and our families to understand the centrality of reading, the thoughtful discussion of good books, and the art of reading good books by the light of the Holy Spirit. As teachers and parents in Zion, the cultivation in our homes of milieus of eternal progress is the key to the spiritual and intellectual development of our families.

Like most parents, I would wring my hands over my children. But one evening two of my three children (the other one, always an avid reader, was out on a date) gave me hope. On saying my good nights I found, in two separate bedrooms, a fine young son and daughter—both engrossed, for a change, in good books. Acting nonchalant, I said, to each of them, “It’s late,” for it was—and that is what any father is expected to say at 11 o’clock on a school night. Reluctantly, for as far as I was concerned they could read all night, I said, “Don’t you think you should turn out your light and get some sleep?” “Oh, Dad,” they said, in their different ways, “don’t bug me; I’m at a really good part. I’ll quit when I reach a good stopping place.” Sidling triumphantly into my own room, thrilled at having witnessed genuine excitement for reading, I began to express to my wife my hopes for a literary progeny. “Shuusssh,” she muttered, reaching for a peanut-buttered saltine, “I’m just about at a stopping place.”

But I knew better, I thought, reaching for my own book and seeing “in my mind’s eye” my own dear parents reading in their long-ago bed. With literature, as with the arts, as with faith—and life—there is really no good stopping place.

Five Blessings of Reading

1. In reading, we experience one of the greatest pleasures human life can afford us; books sweeten, nourish, brighten, and enrich our lives.

2. Books enable us to live more lives than the one allotted and allow us to experience impossible adventures.

3. Books help us to process, order, and understand our personal experience and gain perspectives on others’ lives.

4. Books enable us to see outcomes where we presently see only possibilities; solutions where we presently see only dilemmas; direction where we presently see only impasse.

5. Books allow us an opportunity to learn how to discern the Holy Spirit and respond to its promptings.