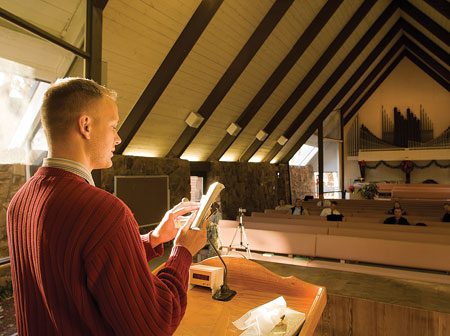

In Sunday best, Jacob R. Snell (’10) grips the pulpit, ready to address the small congregation seated in the pink-upholstered pews of the Utah State Hospital chapel. Below him, BYU religion professor Roger Keller adjusts the video camera, then gives the cue to begin.

Military chaplain candidate Jacob Snell preaches to his classmates – the first LDS chaplains to be trained entirely at BYU.

“Let us read the word,” Snell calls out, citing verses in Amos chapter 5, and the audience rises to their feet. Snell’s oration lasts 10 minutes, filled with powerful hand motions, voice inflexion, and scripture. At the end, his audience—the first students to pursue BYU’s new master’s in religious education for military chaplains—picks his sermon apart.

They are learning to deliver nondenominational sermons: as future chaplains they will be the religious presence on a military base, charged with providing or finding religious services for everyone—Protestant, Catholic, Muslim, or Jew. At present there are 63 LDS chaplains on duty throughout the world who provide these services. And the seven students meeting here in the Utah State Hospital chapel will soon join them as the first LDS military chaplains to be trained entirely at BYU.

Keller, director of the new BYU program, says that in the past a path for LDS chaplains was “kind of bubblegum-and-baling-wired together.” The Department of Defense requires chaplains to have at least 36 hours of graduate-level religion credit, and, while some LDS chaplains completed their secular coursework at BYU, they had to utilize seminaries and divinity schools around the country to fulfill this religion requirement. The only graduate religion program offered at BYU was reserved for seminary and institute teachers in the Church Education System (CES). “We’d send a candidate out to the University of Chicago—which has a great seminary,” says Keller, “but their training was not rooted in the Restoration. Chaplains are to be rooted in their own denomination.”

After years of working with CES, the Church Military Relations Department has finally achieved a place for chaplains at BYU: chaplain candidates can now apply alongside CES students for the 15–17 slots available in BYU’s one graduate religion program. The first seven chaplain students were accepted last summer.

“Ideally, we would like every [LDS] chaplain candidate to go to BYU to receive a master’s degree in religious education,” says Frank W. Clawson, director of the Church Military Relations Department. “It’s an opportunity for military chaplains who are members of the Church to be grounded in LDS theology and doctrine. With the elective courses in this new program and in other disciplines at BYU, they’re going to come into the chaplaincy with some excellent training.”

An additional 15 credits of religion were created solely for BYU’s student chaplain candidates, classes including Military Ministry and two semesters of advanced world religions. They are taught by Keller, who served as a Russian linguist for U.S. Army Intelligence, as a chaplain at a Presbyterian college, and as a Presbyterian minister before joining the Church and teaching at BYU.

In the military, chaplains can disclose their denomination if they choose, but they are not allowed to proselyte. Even so, Clawson emphasizes that LDS chaplains are still ambassadors for the Church. “They ensure that each person in the military and their families are afforded religious freedom,” says Clawson. “They assist in strengthening members of the Church as they serve in the military. And they work side by side with chaplains of other denominations in a congenial, ecumenical way.”

“For me, one of the biggest incentives [to study at BYU] is the theology that’s taught,” says chaplain candidate Loren R. Omer (BS ’01). “It’s familiar to me. … The courses are designed to understand other religions within the context of an LDS perspective, which is something I really appreciate.”