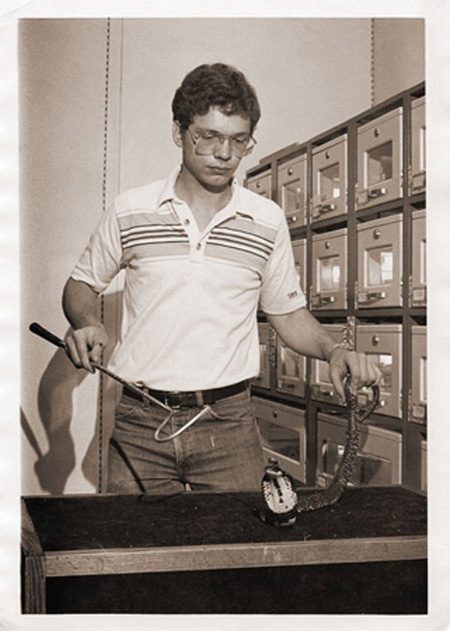

A reptile-lover from childhood, Mark Seward was practically in heaven while caring for a spitting cobra (above) and other animals in the Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum’s reptile collection as a BYU student. He is now an expert on Gila monsters.

Orders keep coming in—from China, Russia, Spain, Brazil. Mark T. Seward (’84) fills them as fast as he can, but it’s hard to keep up with demand.

What does Seward have that is so hot?

Gila monsters, the only venomous lizard native to the United States.

Seward, a retired dentist who lives in Colorado Springs, Colo., is an expert on Gila monsters. He wrote the book Dr. Mark Seward’s Gila Monster Propagation; has appeared in programs on the Discovery, National Geographic, and Animal Planet channels; and possesses what is believed to be the largest group of captive Gila monsters in the world—approximately 100 in all. His basement, where he keeps the lizards, once came in sixth on the Travel Channel’s list of the world’s “Top 10 Creepiest Places.”

Creepy or not, the lizard colony gives Seward a chance to study and breed one of the reptile world’s most mysterious creatures.

Seward’s interest in reptiles was sparked in high school when he joined the herpetology club; on field trips he developed a knack for catching just about anything that moved. Seward took his reptile passion to BYU, where he worked at the Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum and cared for the reptile collection. Before the late Steve Irwin—the Crocodile Hunter—made it hip to love reptiles, Seward was handling snakes, studying lizards, and developing a fascination for the Gila monster.

“They are so unique,” says Seward of the little-understood lizard. Gila monsters eat only three or four times a year, store up fat in a lumpy tail, and spend approximately 99 percent of their time underground.

When Seward retired from his dental practice because of nerve damage in his hand, he turned his attention to Gila monster research. “So little is known about them,” says Seward. “I [was] interested in studying them as a long-term project.” In that pursuit, he got the blessing of his wife and two daughters—who don’t share his passion for reptiles—to turn their basement into a Gila monster dwelling and high-tech research lab.

Using sophisticated equipment, he programs the basement’s temperature, humidity, and light cycles to mirror the daily and seasonal changes in the lizards’ native habitat. Seward also installed video cameras in the breeding cages and uses ultrasound to monitor reproductive cycles.

Breeding the Gila monster in captivity has been a longstanding challenge, not successfully accomplished until the 1970s. Seward was successful on his first try but says it has taken him years to get it down to a science.

His research is widely recognized in the field. “Mark’s understanding of Gila monster reproduction is considered to be among the [best], if not the best,” says Dale DeNardo, an associate professor in Arizona State University’s School of Life Sciences who has been studying the Gila monster for a decade. Seward has assisted Arizona State with field studies and provided the university with animals for research; in turn, the university has shared temperature data with Seward for his own studies in Gila monster metabolism and egg incubation.

All 86 eggs produced by Seward’s Gila monster clan last year hatched, and each of the new lizards had a home: many went to zoos throughout the world, some to universities for research, and others to private collectors.

Not everyone is a good fit for a Gila monster, which can cost $1,000–$2,000. They are illegal to keep in some states, and they have sharp teeth. A bite, though not fatal, has been described as so painful it makes victims wish they were dead.

That’s enough to scare most people away from the Gila monster; but what scares most people only intrigues Seward.

Seward’s only bite came while researching a potential use of Gila monster venom to treat type 2 diabetes. “I was drawing blood from the tail of a monster, . . . and I failed to realize that the monster had gotten out of its restraint,” Seward says. “At least I didn’t notice until I felt the searing pain in my hand. I looked at my hand and noticed there was a monster attached.”