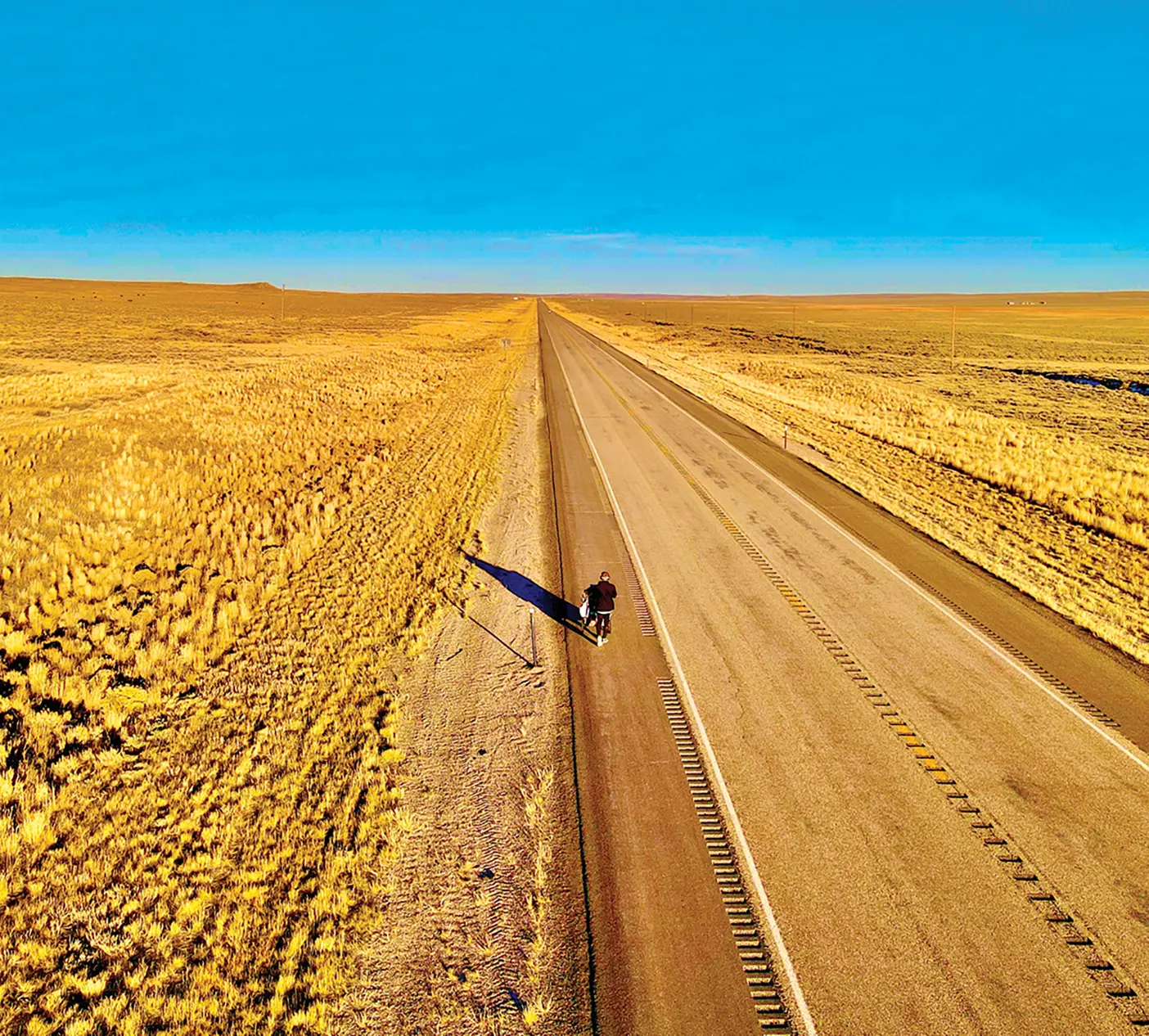

An alum has spent nearly 600 days walking across the United States and Europe. What has he learned? The world is good.

“When I first started walking, the idea just sounded cool,” says Isaiah G. Shields (BS ’19). “My life just wasn’t where it needed to be. I didn’t know what I was doing wrong, but I just felt this great sense of unrest, like there was something bigger.”

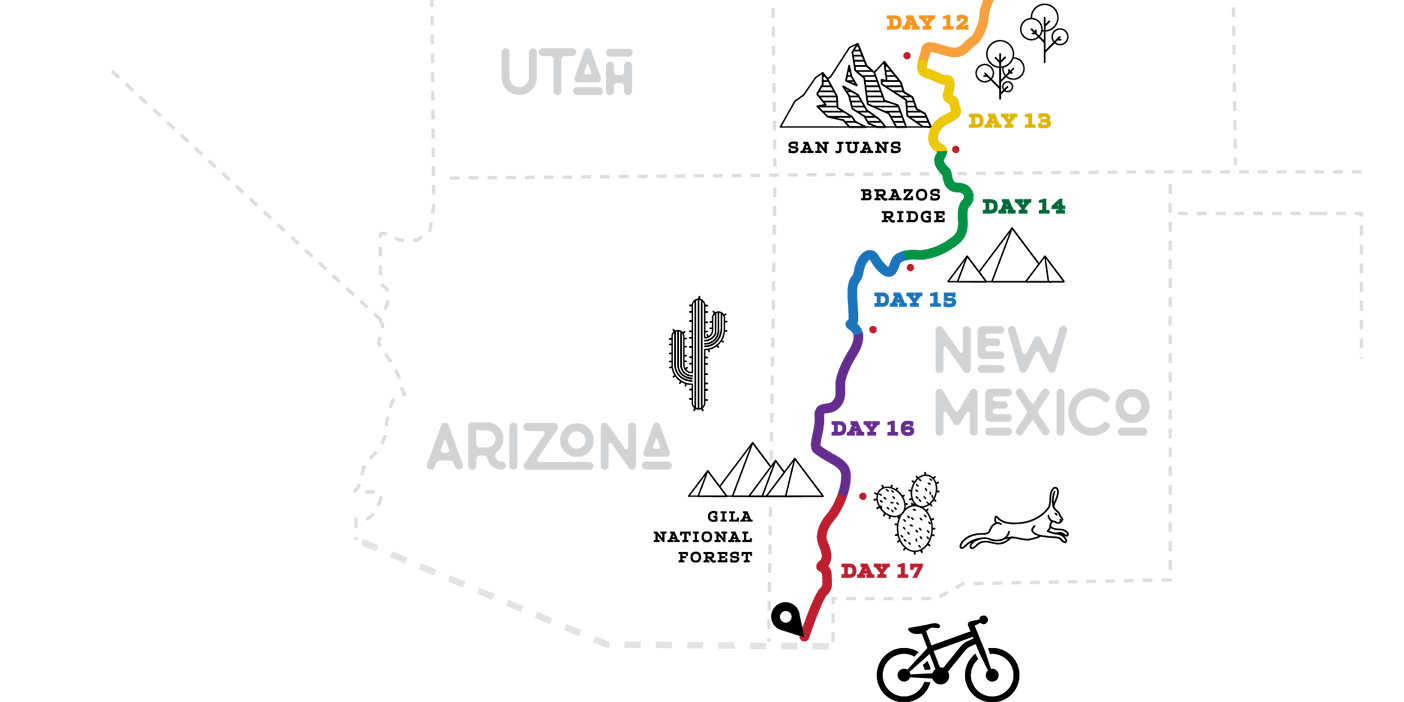

Shields set out to find that “something bigger” by packing a cart with minimal supplies and hitting the road. From Utah he set out for the farthest-west point in the United States, in Washington, then stopped by Texas before ambling along the Gulf Coast and Eastern Seaboard until he reached the easternmost point in the United States, in Maine. In Europe he walked from the northernmost point down into Finland and Sweden.

Shields isn’t in a rush, always stopping to talk to people he meets along his walk. The generosity and vulnerability of total strangers has built his faith in humanity. He created accounts on multiple social-media platforms to share “the many stories of people who treated me with kindness,” he says. The world, he discovered, “is 99 percent good.”

What has Shields learned in nearly 600 days of walking? “Besides me figuring out . . . what I need to work through and improve on as a person,” he says, “I also realized if you want to do something, the only thing that’s stopping you from doing it is working on it.” But mostly he’s learned about people: “Over the thousands of miles drumming the asphalt, the times that all shine are the times I connected with other people.”

Shoe Sponsor

When Shields walked into a shoe store to replace his well-worn shoes, a woman noticed that he didn’t even try them on. Shields explained, “I’ve been walking for 3,000 miles. I know which ones work for me.” Impressed, the woman paid for his shoes. A few months later she offered to buy him another pair in exchange for letting her walk with him for a day. While her husband followed in an RV, they walked 37 miles of Wyoming, just talking about life. “She told me about recovering from alcoholism, the impact it had on her, the support of her husband,” Shields recalls. Since that day, the couple has sent a pair of shoes to Shields every time he wears one out.

Making Friends

People often stop on the roadway to give Shields food or cash, strike up a conversation, and even invite him to trade his tent for a roof over his head. In Slidell, Louisiana, a woman who offered Shields a spare room asked him, “Who hurt you?”

“I sort of broke down,” Shields says, realizing that part of his motivation stemmed from a past painful experience. The woman had understood this because of her own struggles. “Even though we had so many surface-level differences, the things that define us as human we have in common.”

Hanging On

“I’ve had two people tell me that they were close to committing suicide and then did not do it because they saw me walking,” Shields says. “One of them phrased it as, ‘I’m just going to hold on until this guy finishes the walk. I’m going to see if he makes it.’ And then, by the time that happened several months later, she said she was in a much better place and no longer was interested in taking her own life.”