At 7:15 p.m. on a late-March evening, I weave my way through a swarm of students, families, and professors scrambling to fill the few remaining seats of the 900-seat auditorium in BYU‘s Joseph Smith Building. The crowd has been gathering since 7:00, and it is evident there will not be enough room. After five minutes, I finally find a seat two rows from the back, off in a corner. With still 10 minutes and only a few places remaining, I’m not picky.

Amid the general buzz of anticipation I pick up snatches of conversations–a montage of curiosity, excitement, and anticipation. As the minutes pass, those who can’t find seats begin to line up against the back walls and sit in corners. At 7:30 someone offers a prayer, the room darkens, and the Best of Final Cut begins.

For the 15 students whose names appear on the program next to their films, finding a place in BYU’s student film festival takes much more than a $4 ticket and a 30-minute wait. Years of anticipation; arduous classroom training in theory, history, production, genre, and ethics; and a fair share of trial and error behind the camera all come into play. And before their dreams will ever meet the screen, students spend countless hours and several semesters writing and analyzing screenplays, holding auditions, rehearsing scenes, building sets, shooting film, and editing takes. All this they do to sharpen and hone their skills, with the eventual hope of a few minutes of undivided attention from nearly 1,000 viewers.

It was for such a potential audience that two film students in 1992 worked with faculty to create a forum for showing student films. The result of their efforts was the first Final Cut, a one-night screening of student films before an audience of 200. Until then, says Thomas J. Lefler, advanced production teacher and a project coordinator for student films, “students would  leave BYU with films under their arms, but the films never would have been seen by an audience.” The screenings have been of monumental benefit to BYU’s film program, he says. “The moment we began doing Final Cut, the quality of the product jumped significantly. The screening has done wonders in terms of lifting students’ expectations.”

leave BYU with films under their arms, but the films never would have been seen by an audience.” The screenings have been of monumental benefit to BYU’s film program, he says. “The moment we began doing Final Cut, the quality of the product jumped significantly. The screening has done wonders in terms of lifting students’ expectations.”

As the quality of the  productions has increased over the years, so has the size of the audience. Due in part to student-created promotional trailers shown around campus, the film review has developed into a weeklong campus event attended by thousands. This year, faculty cut nine hours of dramatic narrative films, documentaries, and

productions has increased over the years, so has the size of the audience. Due in part to student-created promotional trailers shown around campus, the film review has developed into a weeklong campus event attended by thousands. This year, faculty cut nine hours of dramatic narrative films, documentaries, and  advertisements down to a pair of two-hour programs to be shown throughout the week of the Final Cut. A group of judges, students, and faculty then whittled those two programs down to the two-and-a-half-hour Best of Final Cut–14 films, each between 30 seconds and 20 minutes long–to be presented on Saturday night. And after turning 300 people away from the crowded theater that evening, organizers added another showing.

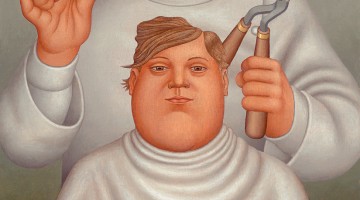

advertisements down to a pair of two-hour programs to be shown throughout the week of the Final Cut. A group of judges, students, and faculty then whittled those two programs down to the two-and-a-half-hour Best of Final Cut–14 films, each between 30 seconds and 20 minutes long–to be presented on Saturday night. And after turning 300 people away from the crowded theater that evening, organizers added another showing.  “On the solemn streets of suburbia, the diligent salesman is hard at work.” Thus begins The Salesman, a black and white silent film meticulously patterned after the early comedies made famous by Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, and Charlie Chaplin. The film flashes down to the audience, and for 20 minutes we are captivated. We watch, entranced by the simple story of a struggling shoe salesman, told by the hero’s animated, energetic movements, at pace with his quick wit and the film’s lively score. While the spell lasts, we are convinced that soundtracks and special effects are still on a distant horizon.

“On the solemn streets of suburbia, the diligent salesman is hard at work.” Thus begins The Salesman, a black and white silent film meticulously patterned after the early comedies made famous by Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, and Charlie Chaplin. The film flashes down to the audience, and for 20 minutes we are captivated. We watch, entranced by the simple story of a struggling shoe salesman, told by the hero’s animated, energetic movements, at pace with his quick wit and the film’s lively score. While the spell lasts, we are convinced that soundtracks and special effects are still on a distant horizon.

Matthew Janzen, who  directed, co-produced, wrote, and edited The Salesman, grew up outside Salem, Ore., without much contact with films. In ninth grade Janzen got a video camera and “made tons of stupid, stupid stuff,” he admits. “But in reality, it was probably the best kind of film school I could have had.”

directed, co-produced, wrote, and edited The Salesman, grew up outside Salem, Ore., without much contact with films. In ninth grade Janzen got a video camera and “made tons of stupid, stupid stuff,” he admits. “But in reality, it was probably the best kind of film school I could have had.”

BYU’s team of faculty mentors and teachers agrees that trial and error can be among the best teachers for aspiring filmmakers. “We believe firmly in repentance,” says Stanley P. Ferguson, a BYUassistant professor of theatre and media arts who spent 20 years with Bonneville Communications before coming to BYU three years ago. “We give students a chance to repent of their bad work and move on to something more noble–and hopefully sin no more.”

BYU’s program is designed to give students practical experience, a wide base of knowledge, and an understanding of film philosophy–the combination of which not only helps them master the nuts and bolts of filmmaking but also teaches them how to craft films that have greater impact. “The faculty don’t just teach you how to load a camera,” says Ryan Little, a student filmmaker from North Vancouver, British Columbia. “They teach you about ethics, theory of film, history, and genre.”

The Final Cut reflects this broad education. A year and a half before the April 1999 festival, while taking a film history class, Janzen devised his plan to make a silent film. “Silent comedies, to me, embody everything that is pure and true about cinema,” he says. “Artistically, they are perhaps the most universal language of this century. A guy falling down communicates the same thing in Zimbabwe as it does here.” Janzen, who intended the film as a tribute to 100 years of cinema, says he struggled to not expand  the genre. The natural tendency, he says, would be to approach the film thinking, “Here’s a silent film. How can we make it bigger and better and more ’90s?” But with authenticity as his goal, Janzen researched everything from costuming to acting to directing styles until he felt he could do a silent film right.

the genre. The natural tendency, he says, would be to approach the film thinking, “Here’s a silent film. How can we make it bigger and better and more ’90s?” But with authenticity as his goal, Janzen researched everything from costuming to acting to directing styles until he felt he could do a silent film right.

Right for Janzen meant re-creating the pleasure that emanates from a silent comedy. “You’re not always slapping your knee or busting a gut, but somehow, all the way through you have a smile on your face. It’s 20 minutes of joy.”

As the films end one by one, with their long procession of credits marching up the screen, I begin to feel a certain familiarity with these names. One movie’s director is the next movie’s editor or cinematographer or producer. The brain behind one film is the boom operator of another.

“It is very rewarding to see the teamwork that goes into the films,” says Carolyn Hanson, who, among other responsibilities in the Department of Theatre and Media Arts, works as the Final Cutcoordinator. “The students here participate in every film and support one another.”

“It is very rewarding to see the teamwork that goes into the films,” says Carolyn Hanson, who, among other responsibilities in the Department of Theatre and Media Arts, works as the Final Cutcoordinator. “The students here participate in every film and support one another.”

With the complexity, expense, and time required to make even a short film (Janzen reportedly spent 100 hours straight shooting his 20-minute film), students need all the support they can get. “When you add up all the people you see in those credits during the Final Cut,” says Ferguson, “there are literally hundreds of people working hundreds of hours to fulfill their creative vision.”

Film students also receive support through BYU’s close relationship with the LDS Motion Picture Studio (MPS). Aside from giving students opportunities to work with professional filmmakers on major motion pictures, the MPS joins with KBYU and the Department of Theatre and Media Arts to provide students with their own facility, Film Student Support Services. Students have access to state-of-the-art equipment, including cameras, lighting and sound devices, the MPS in-house film-processing lab, and several high-tech editing machines. The MPS also subsidizes film-processing and post-production costs for students.

Even with this aid, student filmmakers constantly struggle to find ways to manage their budgets, which can run up to thousands of dollars. “Students don’t have a lot of money,” Ferguson says. “They have a credit card and $5, and they want to make a film.” But the resourceful filmmaker is not without avenues for procuring funding. Little paid for his film, The Last Good War, with a scholarship from BYU’s Office of Research and Creative Activities, a grant from the Lucille King Family Foundation, and the coveted Motion Picture Studio grant. Janzen created The Salesman, in part, using theFinal Cut grant–money drawn from the proceeds of the previous year’s Final Cut screenings.

Still, Janzen spent $1,300 of his own savings making The Salesman. “I’m broke,” he laughs, “but fortunately I’m happy with my film. It’s worth the effort and money even if I don’t get any of it back. I’m a better person for having made it.” He and other student filmmakers will be sending their films to festivals all over the country this summer in hopes of winning back some of their money.

A Samaritan merchant, traveling the road to Jericho, stops at the side of the beaten man lying unconscious, facedown on the burning desert sand. He falls to his knees and rolls the man over to inspect his wounds. With anguish in his eyes, the Samaritan reaches for his flasks of oil and wine and administers to the wretch. Although I already know this parable by heart, as I see the Samaritan’s compassion for his neighbor, I, too, feel refreshed and enlivened.

The Good Samaritan, the latest of a recent flourishing of high-quality scriptural narratives produced by BYU students, won a 1999 amateur film award from CINE, a national nonprofit organization that recognizes film excellence. The film was made in conjunction with the LDS Church and Catholic Community Services of Salt Lake City. Jonathan Tanner, a business major and film minor from Glendale, Ariz., who produced the film, says one of the production team’s main objectives was to add subtle innovations to give a Christian audience new insights into this well-known parable, while remaining true to the essential meaning.

“If you’re an LDS filmmaker, you can’t help but have your film influenced by our morals, beliefs, and ethics,” says Little. “It just comes through.”

“We try to steer students in the direction of making films about what they believe in,” says Ferguson, who has among his credits the LDS public service advertisements in the award-winning, ongoing Homefront series.

The films in the Final Cut are charged with their creators’ ideas and feelings on topics ranging from the difficulties of filmmaking to political issues to quirky aspects of Provo culture. And with silent, art, and action films, the genres are equally varied.

For example, film student Ethan Vincent, from Vienna, Austria, created the French-language Brûle (Burned), a subtitled narrative that leaves the audience with impressions more than definitives. Its use of images, such as a dead fish that menaces one of the characters in a dream, evokes emotions and allows viewers to draw their own conclusions.

In contrast, Rumble in the Colony II, created by Brian Judd (known to friends and on the Final Cut program as “Phontaine”), from Sacramento, Calif., is complete with dubbed-in voices, generic fighting sound effects, and choreographed karate that might impress even Jackie Chan. The action-packed comedy, shot over a five-month period in front of the Colony Apartments in Provo, evoked laughter from the opening title to the closing credits 12 minutes later. “The sole purpose was to entertain,” says Judd, who has received some 50 requests for copies of his movie. “That film was fun the entire way through.”

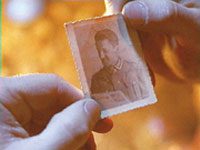

“Germany 1944” appears in white letters on the dark screen. I jump in my seat as a rifle shot shatters the silence; suddenly the room is full of images and sounds of men battling for their lives and liberty in a snowy forest. A grenade explodes and the screen goes black. “The Last Good War” appears on the screen.

Ryan Little got an early start into filmmaking. Growing up in a family with an artistic bent and a love of photography, his interest in photography bloomed into a love of movies when he took a video class in high school, and BYU helped hone his talents and skills. Hailed as one of this year’s best, Little’s carefully crafted film about charity amid the horrors of war earned the coveted spot at the end of the Best of Final Cut.

Ryan Little got an early start into filmmaking. Growing up in a family with an artistic bent and a love of photography, his interest in photography bloomed into a love of movies when he took a video class in high school, and BYU helped hone his talents and skills. Hailed as one of this year’s best, Little’s carefully crafted film about charity amid the horrors of war earned the coveted spot at the end of the Best of Final Cut.

“The thing that amazed me was how well organized Ryan was in bringing together dozens of collaborators to help him tell his story,” says Ferguson. “Good filmmaking comes from good thinking. With The Last Good War, Ryan’s senior capstone project, he was able to show that he could successfully apply the theoretical and practical aspects of filmmaking that he learned here.”

The Last Good War belied the difficulty inherent in filmmaking, as Little combined special effects, music, and authentic props with acting and artistic vision to create an emotional story of brotherhood across enemy lines.

“There are so many opportunities for every film to fall apart that when a film actually works–and especially a student film–it is time for rejoicing,” Ferguson says. “Something in the way of a small miracle has occurred.”

As the screen fades at the end of The Last Good War, the audience erupts into applause. They cheer again at the end of the credits. The lights return, and as we shuffle out of the auditorium, I overhear bits of enthusiastic chatter from those lingering in the foyer. Some students are laughing and mimicking karate moves fromRumble in the Colony II. Their awe at the productions is evident in their voices.

“I was especially impressed with the technical stuff,” someone says in a group of older men. “That’s greatly improved since we were here.”

And near the doors someone says, “Yeah, but what was that fish all about?”

“I don’t know,” another replies. “But I liked it anyway.”

~

Some student films are available for purchase from BYU Creative Works through the Internet (https://creativeworks.byu.edu/) or by phone (1-800-962-8061).

_______

Peter Gardner, a 1998 BYU graduate and former BYM intern, works for the International Magazine of the LDS Church.