By Todd A. Britsch

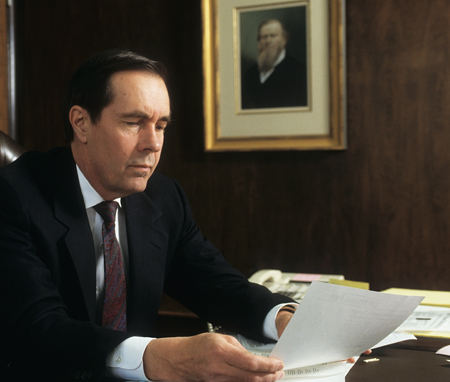

On Monday, March 11, 1996, just over two months after stepping down as president of Brigham Young University because of failing health, Rex Edwin Lee died from the effects of cancer. He served as the university’s 10th president from July 1, 1989, through December 31, 1995, and received an honorary doctorate from BYU six days before his death. President Lee is remembered in this tribute by Todd A. Britsch, a professor of comparative literature and consultant to the president, who served as academic vice president during the Lee administration.

The last time my wife, Dorothy, and I felt comfortable visiting Rex Lee in the hospital was only a few weeks before his death. He had been given some strong drugs before some tests that morning, and he warned us that he might not be completely coherent. But of course he was. Surrounded by legal-sized note pads, and with all kinds of materials on the bed, shelves, and one chair, he was deeply involved in developing one more case for the Supreme Court (a case that he never would argue). Although we had stopped by largely to wish him well, we were immediately drawn into pleasant and amusing conversation, as Rex asked about events at the university, commented on a basketball game, speculated about next season’s football team, asked about our grandchildren, wondered about our plans, and responded so optimistically about his future that we questioned who was really the patient that day. He was very ill, but he simply refused to let that fact dampen the unbounded enthusiasm that he had for BYU, his profession, his family, his Church, and life in general.

As we parted, our last words were declarations of love for each other. We knew that he was sincere, and I believe that he knew the same about us. I have wondered during the past weeks, but especially since learning of his death, why Rex Lee was so easy to love. I suspect that it was because loving came easily for him.

Although Rex and I are close to the same age and both attended BYU, I had only heard of him during my student days. We both were students during the late ’50s and early ’60s, but because of missions and military service, I was never here when he was. I knew of his time as student body president, of course, and Stewart Grow (a popular professor of political science) always used Rex as the example of a real student-scholar. But I didn’t actually meet Rex until he came to BYU as the founding dean of the law school. I suspect that we met in the Richards Building locker room. There he was honing his already slim physique for some marathon, while I was thinking of excuses for losing still another handball game. I would tell him that I could understand chasing a little ball around a court, but that running after thin air was beyond my comprehension. Although I enjoyed our exchanges there and the more serious conversations that we had as he would call seeking assistance in finding more humanities students for his early law school classes, we still had only a passing relationship. My close relations with Rex came only after he was appointed president, but they quickly became deep and rewarding.

Almost immediately, I came to love Rex for his optimism. He simply couldn’t be discouraged. Sometimes, when we were facing a particularly challenging issue, he would mention that this was the one part of his job that he wouldn’t miss. But the conversation rarely progressed for five minutes before he was showing excitement about some solution or, if a solution was elusive, he was diminishing the problem and shifting the conversation to some future adventure. His faith in the gospel, his family, and his colleagues seemed to make it impossible for him to become discouraged for more than a few minutes. He always felt that something better was coming.

This optimism extended to his own medical condition. I would often ask how he felt, and he would be quite honest about his pain and deteriorating health. But he would immediately tell me about a new treatment, or about how he had learned to function with diminished faculties. As the pain of his neuropathy increased, he once told me he was afraid that he might not be able to walk much longer. “But,” he said, referring to a recent BYUSA president who was confined to a wheelchair, “if Jason Hall can do his work from a wheelchair, why can’t I?”

Rex Lee was also the bravest person I ever met. I suppose that only his family really knew how much he suffered, but those of us who had continuing association with him recognized when he was having a particularly painful day. And this happened more and more frequently. But although he would answer questions honestly, Rex simply refused to dwell on his problems. Instead, he would turn his concern to others. Once, when I was feeling the effects of a liver ailment that was causing a bit of pain and tiredness, Rex told me that I should skip a meeting, go home, and get some rest. I was about to leave when I discovered that he was suffering from a bad day with his neuropathy, that his ankles were doubled in size with swelling, and that he also had just come from the doctor who had diagnosed him with pneumonia. And he was staying. When I mentioned the irony of his instructions to me, he replied that he really didn’t feel much different than usual. It was impossible not to love a man that brave.

In an academic institution like BYU, it is common to associate with women and men of quite extraordinary mental quickness, but there are few who could match Rex Lee. He was what some call a “quick study.” He could be brought a problem from an area in which he had little previous experience, and before long he would be asking insightful questions and thinking up examples and counter-examples. He was excited to learn about new things, and he was daring in the leaps he was willing to make. But he was especially quick when the conversation turned to his own field. I loved to ask him questions about constitutional law. His eyes would light up as he cited cases and their possible interpretations. It was an education just to watch this superb legal mind at work.

I suppose that his sparkling wit also came from his brilliant mind. Exchanges with Rex were one of the pleasures of my life, although I rarely got the better of him. But while his legal mind was trained for adversarial relationships, his keen sense of humor was never anything but gentle. The only sharp barbs I ever heard him send were aimed in his own direction. His warm humor made every meeting with him a pleasure. I can’t remember one extended conversation with Rex when I wasn’t brought to smile or laugh. This includes the last one we ever had.

Rex Lee was also a man who never withheld his own love and compassion. During his student days and early years on the faculty, Rex had known my father only casually. But when he learned of Dad’s lymphoma, he took an immediate and personal interest. Rex would call Dad after his chemotherapy treatments, compare drugs and dosage, ask what Dad was reading, discuss scores of games, check on Dad’s blood count, etc. He knew that only a “veteran” of such an experience could guide another through it, and he chose himself as Dad’s guide. It was no surprise that Mom asked Rex to speak at Dad’s funeral.

When he lost his own father, a little more than a year before my dad died, Rex was suffering from blood clots in his legs. Although he desperately wanted to speak at the funeral in Arizona, Rex was confined to bed in the Utah Valley Regional Medical Center. At the same time, our son Dan was in a coma in a hospital in Arizona. We flew to Dan’s side and spent a number of anxious hours before he awoke. In the emergency room in Mesa the nurses summoned us to the phone. On the other end was Rex Lee, calling from his hospital bed to see how our son and we were doing. And that call was repeated. Rex, even at a time when he was suffering from a deep personal loss and a life-threatening illness, was thinking of others.

When we lost Dan about six months later, Rex was scheduled to leave for California within a few hours after we received the news. But true to form, he was one of the first to come to our house. If we hadn’t insisted that he keep his commitments, he may well have canceled all of his planned activities.

Anyone wanting to know of Rex Lee’s capacity for love should have watched him with Janet, his children, and his grandchildren. One image always comes to my mind: We were seated near the Lee family at the Stadium of Fire during one of Provo’s Independence Day celebrations. Rex appeared particularly unsteady on his legs that evening. Whenever he approached the stairs, we were afraid that he might lose his balance. But his grandchildren needed plenty of attention–especially the littlest ones. So he was up and down, getting them treats, drinks, glow-in-the-dark toys, taking them to the bathroom, and just walking back and forth with them when they were sad or losing patience. Pain and loss of equilibrium simply were unimportant when children needed his attention.

Because he was so free with all he had–his energy, wit, optimism, courage, and especially his love–it is easy for all of us to say: Rex, we love you.