Left-Hand Man

For this NFL coach’s assistant, losing an arm has been a challenge—but never an excuse.

By Michael R. Walker (BA ’90) in the Spring 2019 Issue

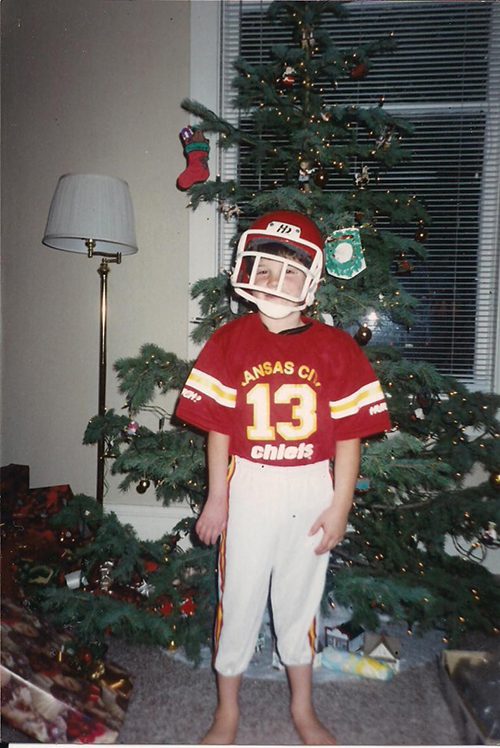

When Porter J. Ellett (BS ’14) interviewed for a senior assistant position with the Kansas City Chiefs’ Andy W. Reid (BS ’82), the coach listed the various job responsibilities, then summed things up: “Basically you need to be me when I’m not here. Or when I am here, you need to be my right-hand man and keep me going in the right direction.”

No problem, Ellett eagerly replied, “as long as you would be okay with your right-hand man not having a right hand.”

The coach laughed. “All right,” he said, “then you’ll be my left-hand man.” Ellett got the job, and the nickname stuck. For the past two seasons, Ellett has been Reid’s shadow, single-handedly managing game plans, scheduling, and other tasks for the veteran coach.

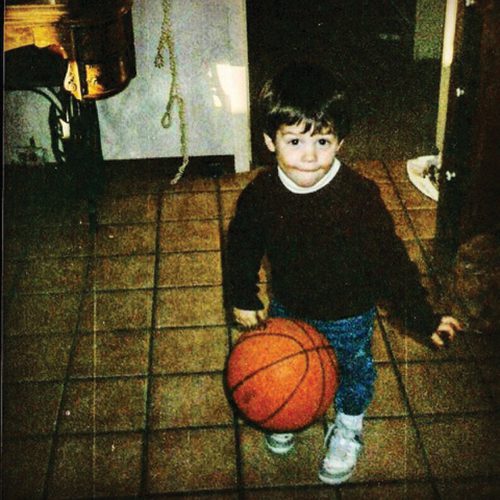

Ellett, who lost the use of his right arm in an accident at age 4 and had it surgically removed at 16, hasn’t let loss of limb, or anything else, hold him back. It was no excuse on the family farm, where he changed sprinkler pipe, baled hay, and drove a stick-shift. Or in sports, where he excelled in high school baseball, basketball, and track. From buttering toast to swimming straight to typing quickly on a computer, Ellett has learned to adapt and to look for the positives in life, lessons he has shared in hundreds of talks as a motivational speaker.

Ellett says growing up with one arm made him a more creative problem solver. “It also changes your perspective on a lot of things,” he says. “I take things seriously and I love to compete, but my perspective . . . is a little different. It’s easier for me to see the positives—even when we lose in overtime at the AFC Championship.”

No Arm, No Foul

When Ellett and his wife, Carlie McKeon Ellett (BA ’13), first show up to church in a new ward, there can be awkward first encounters in a culture where meeting someone typically involves a right-handed handshake.

When he is asked to speak in sacrament meeting, Porter typically shares Matt. 5:30: “If thy right hand offend thee, cut it off”—noting that’s just what he did. “That lightens the mood, and everybody becomes okay with it,” says Carlie.

Her husband’s perspective and peculiar sense of humor were shaped in part by growing up on his family farm in Loa, Utah, a small town about 150 miles south of BYU. “There’s a lot of people in farm towns missing body parts,” he observes.

Ellett’s accident happened when he and a bunch of kids were riding in the back of a moving pickup, taking turns playing on a motorcycle strapped into the truck bed. “I went to get off of it, and I ended up falling out of the truck,” he says.

The accident fractured his skull in three places and damaged the nerves leading to his right arm. “It was the worst combination of an injury,” Ellett says, “because I couldn’t move it, but I could feel pain in the arm.”

After the accident, amid many priesthood blessings and prayers, the family learned that Ellett had narrowly avoided severing a main artery, which would have been fatal. “We’ve always felt like it’s a miracle that he was saved,” says his mother, Mary. “Losing his arm was just a minor setback, you know?”

Miracle or not, young Porter still had to learn to live with an immobile arm. He soon grew accustomed to being stared at. “I kind of became aware of how different I was, and that was a challenge,” he recalls. And then there was the daunting array of everyday tasks designed for two hands.

Ellett’s practical parents raised him with “a lot of love but no sympathy, I guess,” says Mary. “So he had to find a way to do things.”

“I had a really hard time learning how to tie my shoes and other little things like that,” Ellett recalls. “My parents, they deserve a lot of credit because they didn’t baby me. They let me struggle, figure it out, so I was able to learn and grow from it.”

To motivate Ellett to learn to tie his shoes, his mom offered to buy him a new pair of Air Jordans. At age 10 he worked it out, wrapping one of the laces around the shoe, then stepping on the lace to hold it tight.

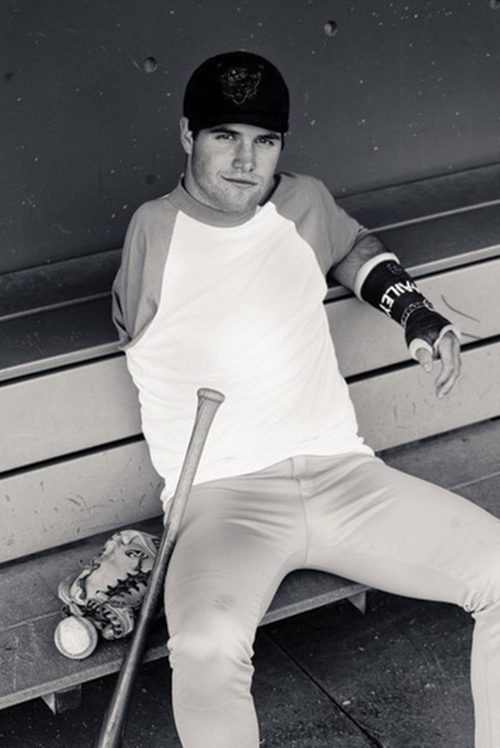

Later, Ellett would defy the odds and master a host of other skills with one hand: tossing sheep into a corral, shooting a shotgun accurately, doing pushups, and batting over .400. Equally impressive, he can zip up a jacket, cross monkey bars, reel in a fish, and ride a motorcycle.

“We tried a bunch of surgeries to try to fix my arm, but nothing worked,” Ellett says. So in addition to helping on the farm—at one point he was bottle-feeding 44 calves—Ellett focused on his athletic abilities. He developed a three-point shot good enough to win a state competition. In baseball, his surprisingly quick “glove-flip” technique—catching the ball, flipping it in the air while dropping his glove, then grabbing the ball again to throw it—is both artful and efficient.

Even so, Ellett’s right arm often got in the way. “There were times in basketball where it would accidentally hit somebody, and I’d get called for a foul,” he says. “Or, even worse, I would hit myself.”

In a game at age 16, Ellett dislocated his shoulder and elbow and broke his right arm—for the sixth time. He’d had enough. During the hour-long car ride to the nearest hospital, he said, “Mom, can we get it amputated? I don’t want to deal with this anymore.” She said, “That’s up to you.”

Later that year Ellett had his right arm removed. Of the operation, he mentions only one regret: “I ended up missing the state cross-country meet that year.”

![A designed quote that reads: "[My parents] let me struggle, figure it out, so I was able to learn and grow from it."--Porter Ellett](https://magazine.byu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Ellett_quote1_f.jpg)

DOn’t quIT!

One year Ellett’s Grandma Shirley gave him a gift of a framed quote: “DOn’t quIT,” the capped letters spelling out Spencer W. Kimball’s prophetic plea. Ellett was a “little disappointed in the gift when she first gave it to him,” says Mary, but he still displayed it in his room. But the quote would come to mean a lot to him.

Ellett’s dad, Jan, coached his son in basketball from early childhood into high school. During Ellett’s junior year, however, his dad lost his job as coach. Porter took this hard and decided he was going to quit the team. He went home, lay on his bed, and cried at the thought of not playing a game he loved. Eventually, his eyes settled on his grandma’s quote: “DOn’t quIT.”

He picked himself up and never looked back, a DOn’t quIT attitude becoming his hallmark. In baseball, he was 1A MVP as a junior and selected as first team all-state his senior year. In basketball, his Wayne County Badgers won the regional championship and were invited to New York City for an appearance on Good Morning America.

Ellett’s athleticism and response to adversity brought him other attention, including an article in the New Era that would change the course of his life a few years later.

When Ellett returned home from a mission to Los Angeles, he enrolled at BYU. One day while collecting fast offerings at the door of an apartment in his ward, he noticed a girl inside intently watching SportsCenter and obviously annoyed at this interruption. Ellett thought, “Okay, this girl’s cool.”

From her sofa inside, Carlie McKeon noticed that this guy at the door was missing an arm. Suddenly it clicked. “This is going to sound weird,” she asked, “but are you the kid from the New Era?”

“From there, we started talking, went to all the BYU sporting events together, eventually started dating, and here we are,” says Carlie. The couple has been married for seven years and has a son named Brigham and a little girl on the way.

“When they did the New Era interview,” Ellett recalls, “they asked me, ‘If there was one thing that could come from this article, what would you want it to be?’ And I said, ‘I just hope that it blesses one person’s life.’ It ended up that the one person was me. I met my wife because of that article, really. She wouldn’t have known who I was.”

In addition to their passion for BYU sports, the Elletts share a love of Halloween and enjoy incorporating Porter’s missing arm into their costumes. Past costumes have included Ammon and a Lamanite, the “soul surfer” Bethany Hamilton and a shark, and Woody from Toy Story 2.

Ellett’s ability to laugh at himself comes from his family, as well as his good friends from school. “When he got his arm amputated,” Mary says, “his buddies wanted him to bring it home. And they planned to bury it by the first base and have a little funeral. We asked the doctor, and he said, ‘No, I can’t let you have it.’”

Of such lightheartedness, Ellett’s mother says, “You have to laugh or cry, and I guess we have decided to laugh.”

![A quote which reads, "I think [losing an arm has] blessed other people, helped them deal with their struggles, more than it's hurt me."--Porter Ellett](https://magazine.byu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Ellett_quote2_f.jpg)

From BYU to the NFL

After graduating from BYU with a bachelor’s degree in economics, Ellett began working long hours as a tax analyst with Goldman Sachs in Salt Lake City. He was grateful for the good job, but he thought about sports constantly. In his free time, he and coworker Vandes A. Price (BA ’14) would use spreadsheets to evaluate athlete performances in baseball, basketball, and football.

After one long day, sensing that Porter was just sticking it out to provide for the family, Carlie asked him, “Do you really love what you do? Can you see yourself doing this for 20 or 30 years?”

Porter shrugged it off and kept working. But Carlie kept asking, so he finally said, “Okay. You’re right. I don’t love what I do, but 90 percent of the world’s like that.” And she said, “We don’t have anything right now that’s holding us back. Let’s take a chance.”

Porter confided that he would love to find a way to make his passion for sports into a profession. And so, after evaluating sports-management programs, he earned a spot at Baylor, obtaining a master’s degree in 2016.

A connection from his BYU days led Ellett to his first big break. But it wasn’t from his championship intramural softball team or from doing laundry for the football team; instead, it came from teaching Spanish at the MTC. Ellett and a fellow teacher, Devin Woodhouse, shared a love of athletics and had coaching aspirations, so the two friends made a pact to help each other in their careers. Woodhouse married Drew Reid (BS ’12), daughter of NFL coach Andy Reid, and the couple became fast friends with the Elletts.

On an icy day in December 2016, Carlie and Porter ventured to Kansas City to attend a wedding and see a Chiefs game with Drew and Devin, who was then working for the team. Afterward, they were invited to the Reid home, where Drew asked Porter about his life, which, with fellow alum Andy listening in, became a kind of casual job interview. The coach was impressed. “After the season I had an opening, so I ended up bringing him in, interviewed him with a couple other guys, and thought he was the best,” says Reid.

Over two seasons as a senior assistant, Ellett has become a key member of the Chiefs team with his hard work and positive energy, Reid says. “He’s relentless, has a phenomenal personality, and everybody trusts him.”

Ellett worked with the Chiefs’ equipment guys to create a modified sweatshirt with a pouch sewn in front so he can have play cards sorted and accessible for the coach. “He’s got them all categorized like a filing system, and he just pulls them out when he needs them at practice,” says Reid. “Now some of the guys with two arms are getting them made so they can be hands free out there.”

Ellett’s attitude has also impressed other team members, according to Drew Reid. “He’s always smiling. Everybody says he has the hardest job with the longest hours. My dad really needs it to be done well,” she says. “And at the end of a season, everyone is exhausted, but Porter is still pumped, saying, ‘I can’t wait for next season.’”

On the practice field, Ellett has been known to rib Chiefs receivers when they attempt a one-armed grab and drop the ball. “Our rule around here, guys, is if you have them, use them. If you have two, you’d better use two,” he tells them. “And the players will always laugh and tell me, ‘That’s messed up, man.’”

When most would think only of the negatives of losing an arm, Porter looks at the advantages, including being memorable but, more important, allowing him to be a role model for those with disabilities. “I think it’s blessed other people, helped them deal with their struggles, more than it’s hurt me.”

When he talks to youth at firesides, he tells them, “You should laugh at yourself. You should smile. You should ignore people whose opinions don’t matter. Pick the three or four people you are going to listen to. For me, my parents’ opinions matter, my wife’s, God’s, and then Coach Reid’s, as far as my job goes. Pick who you’re listening to and just listen to them.”

When asked about the future, Ellett says his dream is still to coach one day. But for now he is just “focusing on doing my best at what I’m doing. I think that’s important.”

And he is thrilled to observe and assist Reid. “I’m learning so much from him as far as teaching the game of football, but also the structure you need to build a successful team,” he says.

He was also grateful to learn about the coach’s brother who had a similar accident affecting his arm. “[Coach Reid] knows how to deal with somebody who has a disability but, like me, doesn’t want to be treated like they’re disabled,” Ellett says. “He’ll tell people, ‘No, don’t think he can’t do something, because he can do it.’”

Reid says it comes down to determination and will: “Porter’s a talented guy. He refuses to be denied.”

Opening photo by Brad Slade.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.