Leaving or Believing?

So which is it? When it comes to current trends in faith and religion, practitioners and observers can be forgiven for feeling confused.

On the one hand, religion lately seems to be hitting a groove. In popular culture The Chosen, faith-based music, and spiritually themed movies are gaining social traction. Latter-day Saints are cheered by gathering momentum backed by hard numbers: convert baptisms are at an all-time high, Church Educational System institution enrollments are swelling, and young people are signing up for missionary service like never before. The scores of temples in planning or construction today often feature multiple baptismal fonts to accommodate the burgeoning demand for youth participation.

Things, it seems, have never been better.

On the other hand, it’s impossible to ignore the persistent slide in US religiosity across nearly all faith traditions. For more than 30 years, Americans have increasingly identified themselves as belonging to no religion; and for those who do, more and more their activity level is what researchers describe as “nominal”—meaning in name only, lacking regular attendance or personal devotions. Few American families are unaffected by the expanding numbers of people who have deidentified or disaffiliated from religion.

Seeing these trends, we might say things have never been worse.

So . . . which is it?

To that question BYU social scientists studying religious affiliation throw out their standard shorthand analyses: “both” and “it depends.” This isn’t just them being slippery. As it turns out, both trends seem to be true simultaneously—both for members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and for other US religionists.

As covered in a 2024 BYU Wheatley Institute report, The Tides of Religion, there are reasons for hope, including some indications of a changing tide in identification patterns. There are even whispers of revival.

The Rise of the Nones

Demographers call the trend “the rise of the nones.” When describing the phenomenon out loud, they tend to spell out the last word—n-o-n-e-s—lest it come across as an unlikely plot about a Catholic uprising. But no, this story is all too real.

People choosing to step away from religion isn’t new. Young people in particular have always been susceptible to changes in their beliefs and religious observance during the identity-forming years approaching and entering adulthood. “That’s not a Gen Z phenomenon,” says Loren D. Marks (BS ’97, MS ’99), a BYU family life professor who studies religion and families and codirects the longitudinal American Families of Faith project. Even so, in the mid-20th century nearly 95 percent of Americans identified with a religion. And those who wandered tended to return to at least nominal religious affiliation.

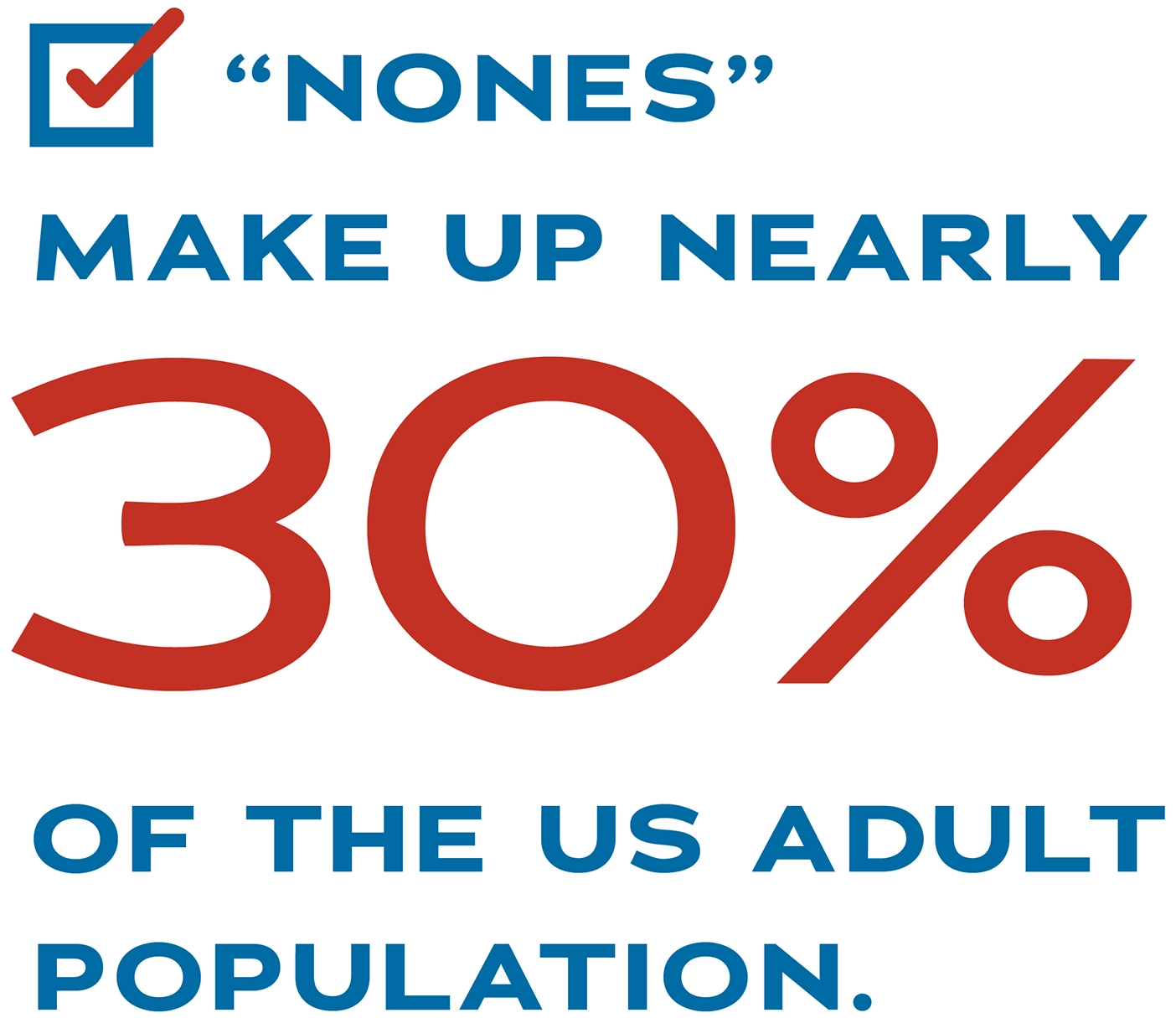

But then, in the early 1990s, religious identification graphs from Pew and others took a decidedly downward turn as more and more people in surveys began checking the box for “none” or “nothing in particular.” Along with those not raised in a religion was a dramatic increase in those who were brought up in a faith tradition but no longer identified with it, a subset sometimes called the “dones.” Together they now make up nearly 30 percent of the US adult population.

BYU psychology professor Sam A. Hardy (BS ’99), who studies developmental psychology, says it’s no coincidence that this trend began just as the internet became widely available. He posits that increased access to information—some reliable and some not—invited new scrutiny of religious organizations, traditions, and faith claims. High-profile scandals involving religious denominations added fuel to the fire.

Religion professor and family science researcher W. Justin Dyer (BS ’04) notes that it’s not just religion that has been under the microscope. “That [organized] religion is declining in the United States is no surprise because it’s an institution, and all institutional connections have been declining,” he says, noting younger generations’ broad distrust of organizations. “We’re just detaching as a society, and religion is part of this overall detachment.”

![Quote: "The number one predictor of leaving your faith is your politics—on either of the extremes. . . . [People] are more likely to go with their politics than with their religion."](https://magazine.byu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/35b_1404x414_W26.webp)

Along with decreased religious identification is widespread slippage in religious behaviors—even among those who still identify with a religion. “Attendance, belief, . . . prayer, scripture study, spirituality—most of those have gone down,” says Hardy, citing various polls of religious behaviors.

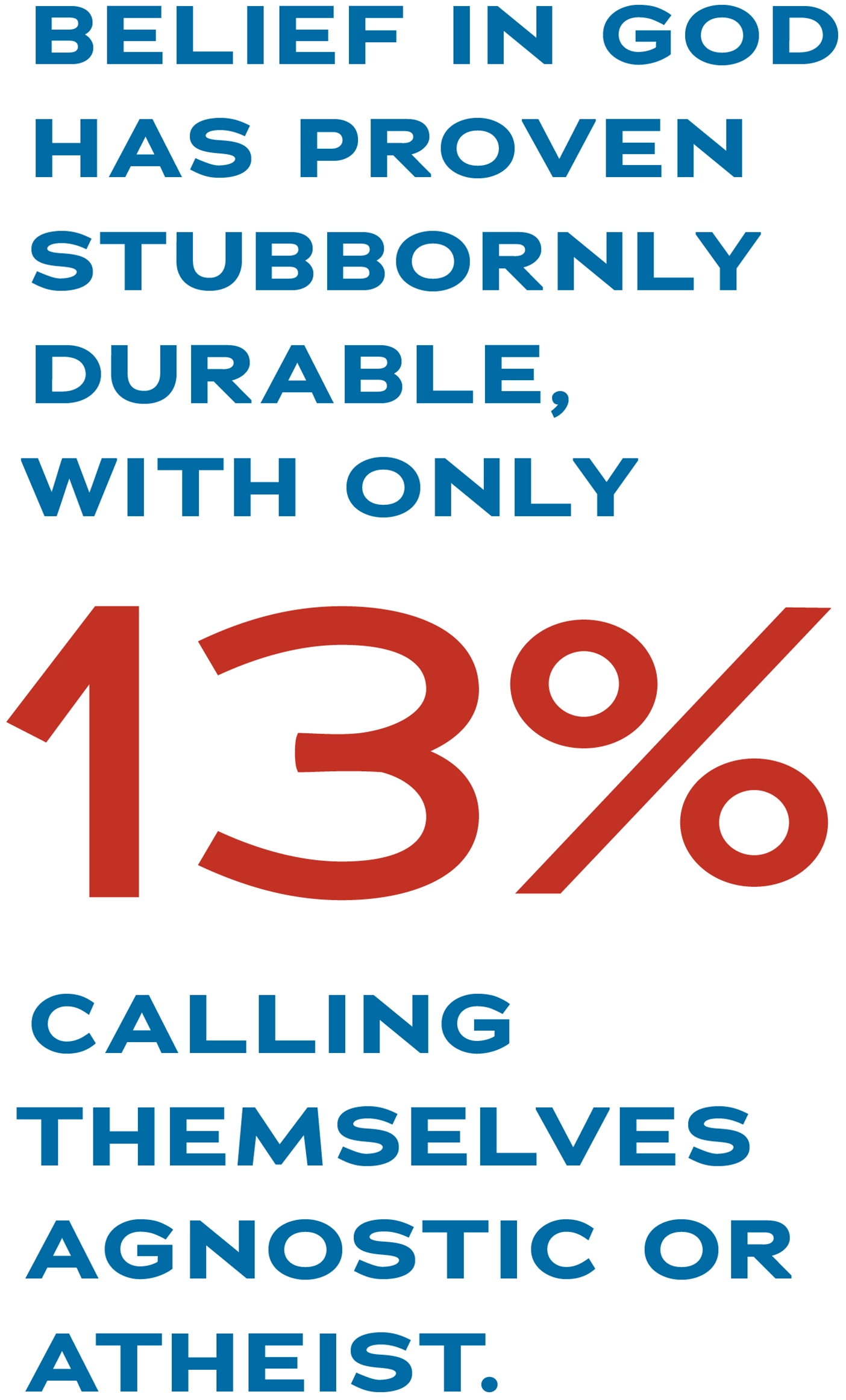

Even amid these sobering trends, some predictions haven’t played out as expected. With the increase in nones and dones, some researchers anticipated a “new atheist movement” to sweep across the United States. While religious identification has dropped off, belief in God has proven stubbornly durable, with only 13 percent calling themselves agnostic or atheist. “People are still, for the most part, believing in God or a higher power,” says Dyer.

Even as the United States remains a believing nation, the declines in affiliation, especially among younger generations, will have a major impact, says Paul W. Lambert (BA ’07), the BYU Wheatley Institute religion initiative director. “There are some traditions that are in crisis right now because 50 percent of their membership is over 65. That’s not good over the next few decades.”

In place of religion Americans increasingly turn to politics for guidance. Where it used to be that Americans interpreted politics through the lens of their religion, today it’s often the inverse. “Many people are willing to change the way they interpret . . . right and wrong based on where their political party is going, even on things that are deeply moral,” says Lambert.

That transfer of moral authority shows up in the data. “The number one predictor of leaving your faith is your politics—on either of the extremes,” says Dyer. “If their religion and their politics conflict, today [people] are more likely to go with their politics than with their religion.”

Exceptional, but not an Exception

For all their care not to jump to conclusions, these BYU researchers say one thing is crystal clear: religious participation leads to a whole array of positive outcomes—from improved mental and physical health to less involvement in risky behaviors to higher rates of giving and volunteering.

“On virtually every outcome, religious practitioners are much more likely to flourish,” says Lambert. “That’s not just a religious argument. That’s also a data argument.”

Many of those life benefits kick in, notes Marks, only as practitioners hit a certain threshold: “When we see individuals move to weekly attendance, things change in their lives”—things like overall health, longevity, and levels of social support. Thus more religiousness means better outcomes.

In that regard, Latter-day Saints stand out. “Pretty much across any measure of religiousness you look at, Latter-day Saints are the highest or among the top,” says Hardy, citing attendance, scripture study, donations, service, and other indicators.

“In terms of behaviors,” agrees Dyer, “we’re the most religious of any major religious denomination in the United States” and have the lowest percentage of members who are nominal only. That holds true for Millennial and Gen Z members.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is what researchers call a “high-demand religion.” Members pay tithing, serve missions, hold time-consuming callings, and weave gospel living into daily life. They’re expected to be spiritual producers, not just consumers. Much is required, but much is also given, notes Dyer. Data affirm that Latter-day Saints are most likely to say they felt “a deep sense of spiritual peace and wellbeing in the last week” and experience strong belonging, among other indicators of members thriving in their faith.

But it would be wrong to declare all well in Zion, the researchers say.

Although the rate of decline has been less precipitous, Latter-day Saints are not immune to the trends. “We’re blown by the same winds that [other religions] are blown by,” says Dyer. “We’re doing better than most religions, but we’re also following the trends.”

Again, reality is nuanced. Lambert says narratives of a “mass exodus” from the Church don’t hold up under the data. But, he adds, “that doesn’t mean no one’s leaving.”

Hardy says those who do leave typically take one of three routes: thoughts, feelings, or behavior—and often a combination. Thinking your way out is “what we think of as a faith crisis—somebody gets new information or they’re researching Church history and feel they just can’t believe anymore,” says Hardy. Feeling your way out, he says, “is getting hurt in some way, . . . some kind of negative experience with people in the Church.” Behaving your way out is “people whose behavior no longer fits with Church [standards].”

Whatever the reason for leaving, recent research by Dyer and Hardy has shown that the path away from religion, especially from a highly demanding one, can be an arduous road to travel. They found that Latter-day Saint dones fare worse on measures of mental health, including toxic perfectionism and suicidality, than those who remain in the faith. They may experience a diminished social network of support, feel a loss of identity, and struggle to develop a new moral framework or find purpose in life. And they’re more likely to engage in risky behaviors.

And this, the researchers say, calls for friends and family of those who leave to be especially mindful of them and intentionally provide needed support and love.

Don’t Call It a Revival

Everybody loves a comeback story—the prodigal sons and the Alma the Youngers. And amid the dreary stats of the last 30 years, some are seeing signs of religion on the comeback trail; there have even been rumblings of spiritual revival.

Reconversion—the term for people returning to faith after leaving it—has not been thoroughly studied, either in terms of measuring how many return or unpacking why they come back. And researchers disagree on how broad any such trends may be.

“It’s complicated,” says Lambert. “There are data points that suggest there is and also data points to suggest there isn’t a revival” going on. But he says there are some indicators of renewed interest in religion among young people. One example: just as CES institutions like BYU have seen swelling applications, so too have religious colleges and universities from other faith traditions. “There seems to be a hunger for this kind of education in the United States,” says Lambert. “I don’t know if that’s a revival, but it’s an interesting data point.”

More broadly, Lambert says that in this era of political and social division, young people seem to be casting about for better ways forward—and some are reconsidering religion. “That’s really encouraging.”

The best indication of change comes from a surprising trend among the nones. After steadily building for three decades, the share of Americans who don’t identify with a religion finally plateaued in 2023 and has held steady since. Demographers note that the numbers will likely climb again as older, more religious Americans pass away. But for now, there seems to be something afoot.

The early evidence suggests that renewed interest in Christianity may be more of a “pocket revival,” largely coming from an unexpected demographic—young men, who Hardy says have traditionally been the least religious and most likely to stray from religion. The gender gap in religiousness has been closing in recent years and maybe even flipping, with men in some ways eclipsing women.

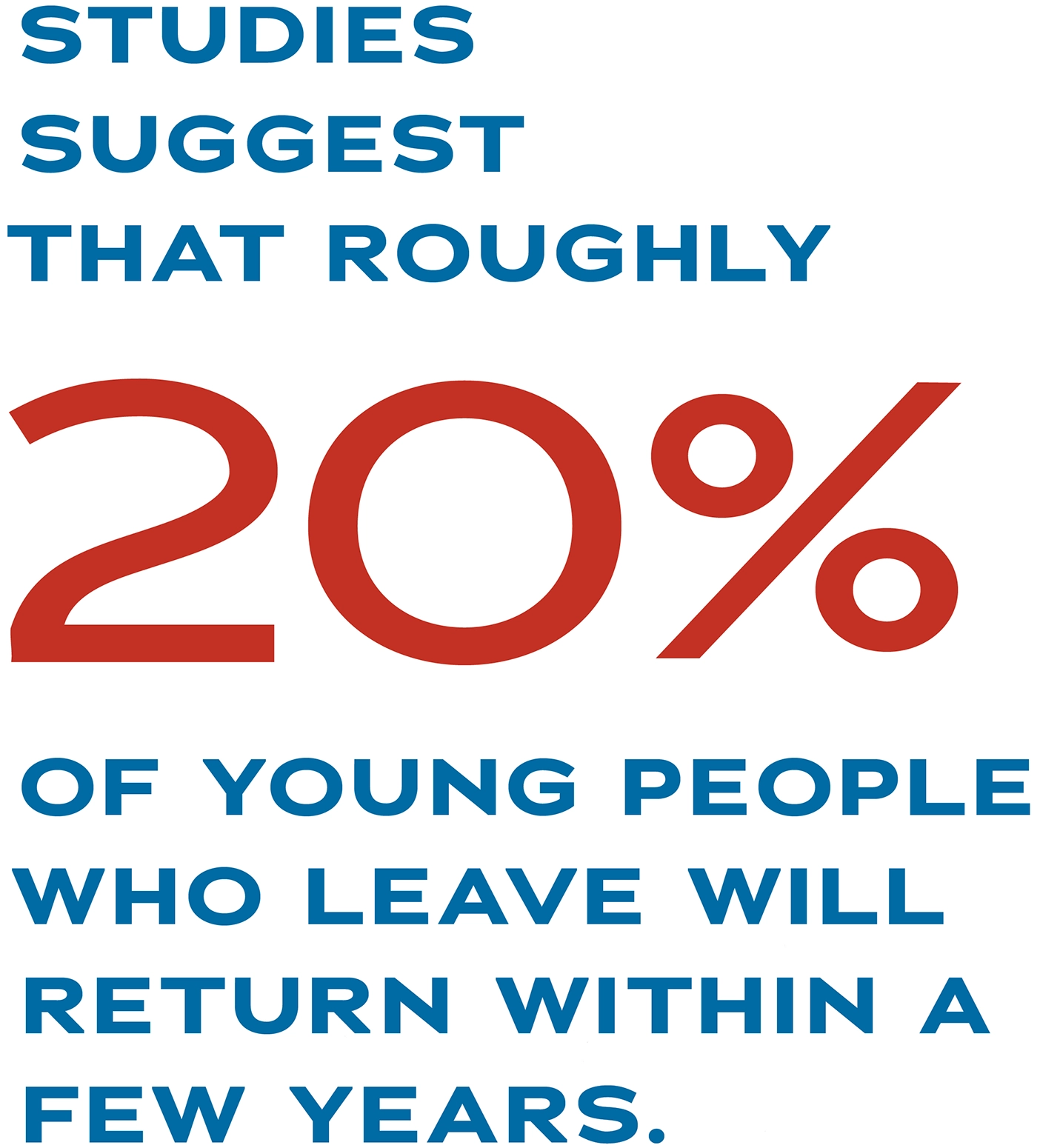

Widespread revival or not, it’s the case that not all who wander stay away. The limited studies on reconversion suggest that roughly 20 percent of adolescents and young adults who leave religion will return within a few years. Some find renewed interest in religion with life changes—such as getting married or having children. Having school-aged children, in particular, correlates with reconversion. Still others return to faith later in life as they face physical challenges and confront their mortality.

And for Latter-day Saints, there are teachings that people can and will return to belief even beyond the grave. And so, while Marks says that the 20 percent figure can “feel like cold comfort,” he believes a much higher number will choose to return throughout life and eternally.

In an informal analysis of reconversion stories, Hardy says people who return typically re-walk the same path they took when leaving. Thus, he says, for those who thought their way out, reconversion would likely involve learning more and having some kind of epiphany or “aha” moment. “Such people will say, ‘You don’t leave because you know too much; you leave because you didn’t know enough. Once you know more, then you come back.’” For those who felt their way out due to a painful experience, coming back might entail some kind of resolution or healing experience. And for those who behaved their way out, coming back might involve recovering from an addiction or otherwise adjusting their behavior.

One national study noted reasons why people choose to return to a church, many of which were practical, not spiritual, in nature—seeking training for the kids, receiving offered childcare and parenting classes, engaging in discussion groups. However, Marks notes that a review of Latter-day Saint reconversion stories conducted by BYU–Idaho professors Eric F. (BA ’00, MA ’03) and Sarah Hafen d’Evengee (BA ’95), found a common element in nearly every case: “The reason people come back is because of a new or rekindled relationship with God,” he says. “It’s a vertical breakthrough.”

The Long Game

With recent trends toward disaffiliation and deidentification, what’s a concerned parent or friend or church leader to do?

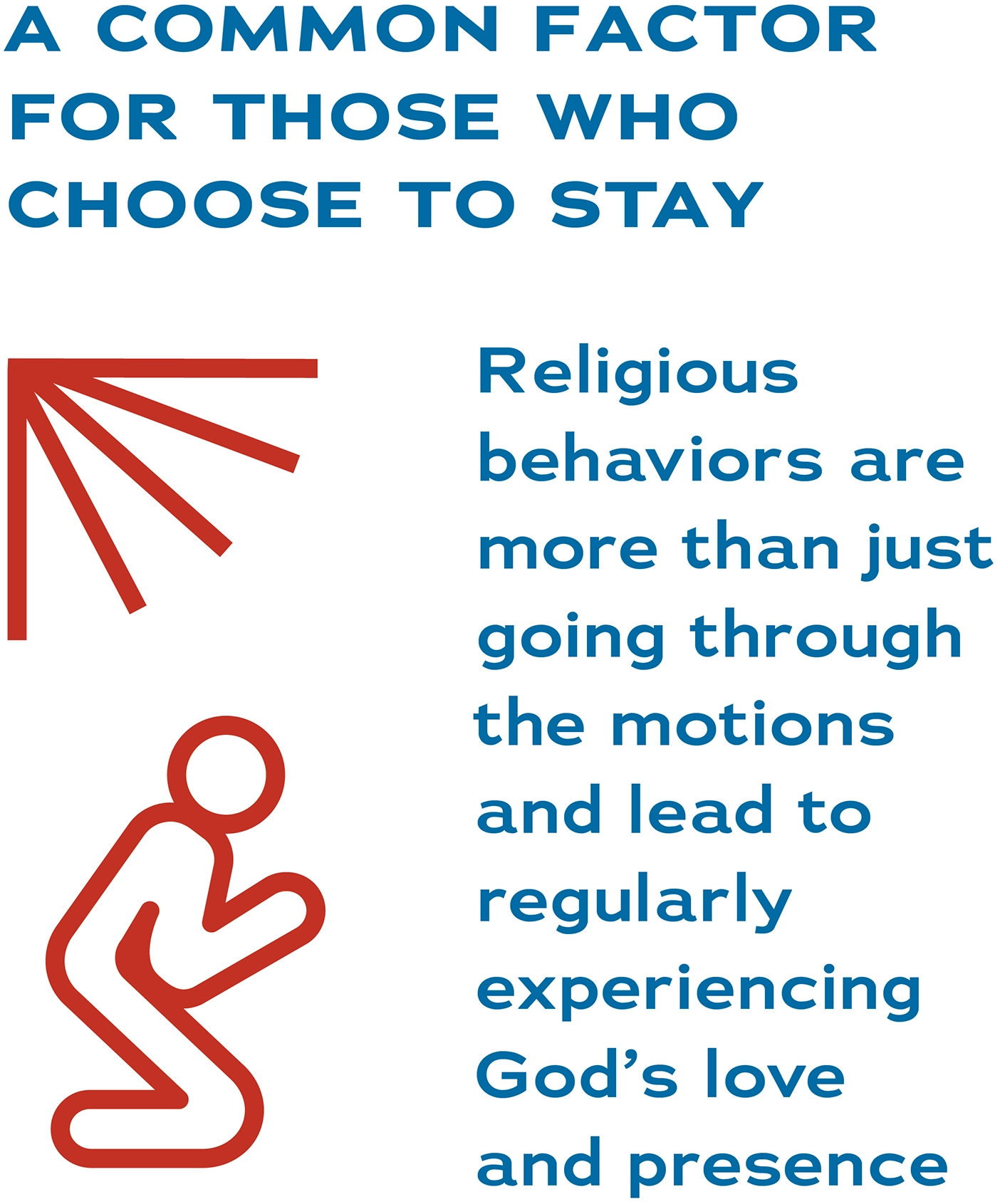

It begins with an ounce of prevention. Although there is no scientific formula to guarantee children will remain in the faith of their upbringing, Dyer says certain experiences are highly predictive of choosing to stay.

Interestingly, on their own, old standbys like scripture reading, prayer, and church and temple attendance don’t seem to have much impact on religious retention. Dyer says it’s only when those behaviors lead to regularly feeling God’s love and presence in their life that young people are much more likely to stay. “It’s got to translate into an actual personal experience with the Divine,” he says. “Connection matters.” And so Dyer recommends that parents and leaders work to guide young people from merely going through the motions of these behaviors to having daily, authentic, personal spiritual experiences.

Even when parents and leaders have provided an ideal spiritual upbringing, agency reigns supreme. Some youth and young adults will experience faith crises or other challenges, and some of those may choose to leave. What should support for these loved ones look like?

“This is as hard an issue as many of us are likely to encounter in this life,” says Marks. “When there’s such deep pain, often on the side of both parties, it takes excruciatingly careful, measured Christlike behavior to navigate it well and in a way that is most likely to leave the door open.”

For starters, Marks says there are a few approaches that are known not to be helpful: fire and brimstone, calls to repentance, forwarding a favorite general conference talk on apostasy, or expressing disappointment and disapproval.

Rather, in such a vulnerable moment, the researchers say it’s crucial to reassure loved ones: although they may have decided to disaffiliate from the religion of their upbringing, they don’t need to disaffiliate from their family or other social networks. Dyer says to focus on areas where there remains overlap and shared interest.

He also says it’s key to honor agency and to offer unconditional love, without judging. Parents and friends can ask sincere questions about the person’s experience and feelings, seeking first to understand and not to persuade.

In such a dynamic, religious conversations can be tricky. And yet Marks notes an important finding from BYU’s American Family of Faiths research: “One of the greatest relationally strengthening activities is the sharing of spiritual experiences with each other.” The researchers suggest asking those who have left the faith what they are comfortable and not comfortable talking about—and to remember that many people who deidentify with religion still have belief in God and may continue to have meaningful spiritual experiences and insights.

Lambert notes the abundance of related teachings in the aggregated addresses of Presidents Russell M. Nelson and Dallin H. Oaks (BA ’54). “Nobody has taught more eloquently than President Dallin H. Oaks on how to engage across difference while standing on truth,” says Lambert. “He’s been teaching this for decades.”

And Lambert points to the clear example of Jesus Christ. “The Savior, . . . all of His invitations were to come,” he says. “My only job, when you boil it down, is to be a mechanism for people to get one step closer to Christ, whether they’re on step 1 or step 1,000 of that journey. We all need Christ at the end of the day.”

Dyer says that, while such actions won’t ensure that spiritually wandering loved ones will return to religion, they can maintain the bridges to faith that will be needed if they do choose to come back. “The best thing to do is to continue loving them and continue holding to your faith. That’s the best way to build a bridge for them to come back.”

And so his counsel, based in a growing body of research on religious identification, affiliation, and conversion, is to “play the long game. This is not the end by any means.”

Read the Wheatley Institute report The Tides of Religion.

Feedback Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.