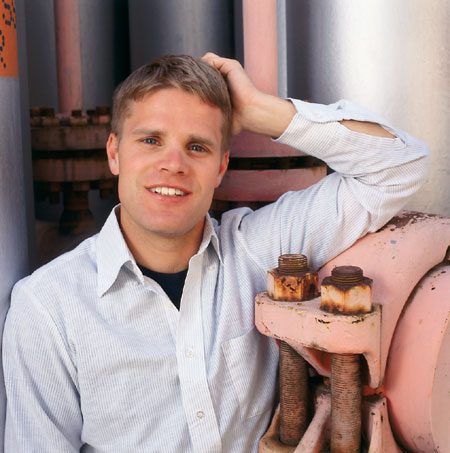

By Michael D. Smart, ’97

IT turns out that the health of your spouse is as strong a predictor for your own health as your level of education and your economic status, two proven health indicators,” says Sven E. Wilson, ’89, an assistant professor of political science who specializes in health economics and demography. His study is reported in the September issue of the journal Social Science and Medicine.

Finding that sick people tend to be married to other sick people has important health policy implications, Wilson believes.

“When addressing health issues, physicians and policy makers should remember the patients involved will often have spouses likewise struggling with their health,” Wilson says. “Consequently, many health policies should be focused on families, not just individuals.” He also says that individuals who have an ill spouse may want to reevaluate their financial plans, since a partner’s condition may be an indicator of their own undetected health problems.

To test his notion that individuals within marriages would often mirror one another’s health, Wilson obtained lifestyle and demographic information gathered from more than 4,700 couples in their 50s in the Health and Retirement Study, a 1992 nationwide survey. He then used statistical models to test how much the subjects’ traits influenced their overall health, as measured by three different diagnostic tools.

For instance, a man in his early 50s who is in excellent health has about a 5 percent chance of having a wife in fair health and a 2 percent chance of being married to a woman in poor health. But a man in poor health has a 24 percent chance of being married to a woman in fair health and a 13 percent chance of being married to a woman in poor health.

Wilson says several factors explain much of the correlation he found. “We know that people tend to choose spouses with similar backgrounds, and we also know that level of education and economic status are proven predictors of health status,” Wilson says. “So if people with the same health-related characteristics are marrying each other, it stands to reason they would have similar health.”

Wilson also found that couples tend to make similar choices after they are married that affect their health—decisions like whether to smoke or drink or what foods to eat.

He also suspects other causes for the correlation—factors that were not observable in the data he studied.

“Spouses obviously share environmental risks—they breathe the same air and are exposed to the same germs,” Wilson says. “Another factor probably at work is that spouses share many of the same emotional stresses, such as problems with children. There is also the burden of being a caregiver for a spouse in poor health, which may take a significant toll on the caregiving partner.”

Because of the propensity for shared illness, Wilson emphasizes the need for the national healthcare debate to acknowledge the importance of examining solutions at the household, rather than the individual, level.

“When spouses find themselves both in poor health, they each lack the support a healthy spouse would provide and both face the additional stress of dealing with the sick loved one,” says Wilson. “In these cases, two sick spouses add up to a serious drain on the financial and other resources of the family and the public.”