From the mail room to the Oscars, a sociology grad works his way up in Hollywood.

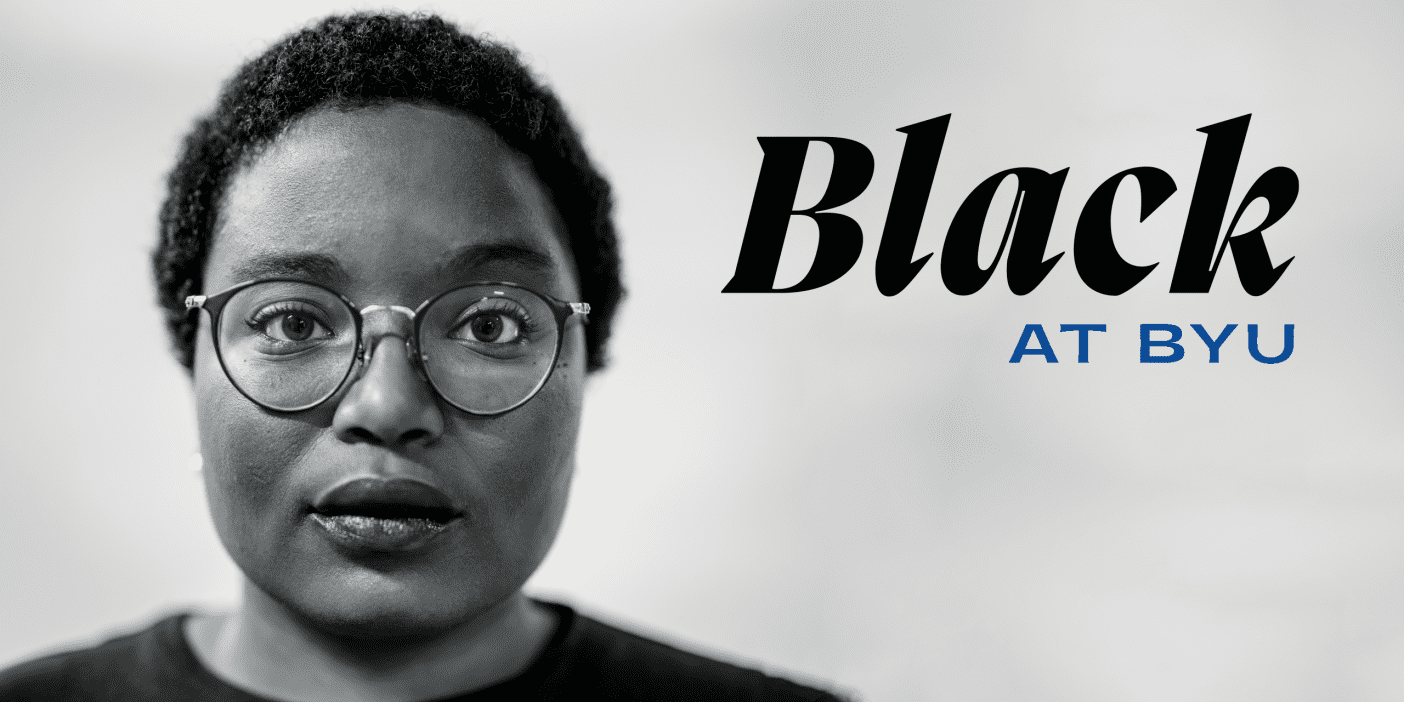

At the 2006 Student Academy Awards, Richard Miller, awards administrator for the academy, poses with actress Nia Vardalos.

Richard D. Miller (BA ’71) has come a long way since he began working in the mail room of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. That was 33 years ago, and Miller now serves as the organization’s awards-administration director and writes and produces the Scientific and Technical Academy Awards.

Miller had no inkling of this career after graduating from BYU in sociology. The appeal of a recording contract had lured him and some of his friends to Los Angeles. Their musical plans stalled, however, and Miller needed to pay his bills. He met a governor of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, who landed him the mail-room spot.

At the end of the summer, as Miller prepared to leave, the academy fired an art director in the middle of a major mailer design. Miller had taken several classes that included page layout, so he applied for the vacant position.

“I asked the employer to give me the director’s job—and his office—if I designed a successful mailer and distributed it,” Miller says. “I got the job, and that mailer was used for about 30 years.”

As Miller worked on posters and magazine covers, however, he knew he’d only be able to take this position so far, not being an artist. “I figured somebody was going to figure it out,” he says.

So he opted for other opportunities in the company and worked on such projects as Nicholl Fellowships in Screenwriting and the Student Academy Awards, which he still runs. He found his niche in 1988, when he was made an executive officer and put in charge of the technical side of the academy.

“We are the awards administration for the craft of filmmaking—the art direction, filming, costume design, visual effects, sounds, sound editing—and the scientific and technical awards,” he explains.

Each year he oversees some 200 workers in the production of the Scientific and Technical Academy Awards. This black-tie event takes place about two weeks prior to the Oscar telecast and draws as many as 600 attendees. It is produced as though it were a live television show, with the same director, production designer, and production crew used on Oscar night.

Miller begins writing the February program in December and weaves in three levels of awards—certificates, plaques, and Oscars. Certificates are given for the development of a significant technology that affects only a particular aspect of filmmaking. Those who have pulled off engineering feats, such as developing a new camera, qualify to compete for plaques. Oscars, though rare, are given for technical advancements that change the way movies are made.

Perhaps most significant, this night is not meant to honor actors.

“While they, admittedly, get most of the glory for successful movies, this industry wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for those dedicated to the science and technology of film,” Miller says. “This event honors those who are often unsung but absolutely imperative to the past, present, and future of the motion picture industry.”

Miller recognizes it is rare to stay in this business for more than three decades, but he says he felt at home immediately. “I had friends from the first day,” he says. “It has been fun to be part of the changing technology, to hear inside stories, and to work with some of the top people in the industry. You can go anywhere in the world and people know about the Oscars. It’s a fun, challenging ride.”

Though he didn’t study film while in college, Miller says his BYU education has been valuable in his career. “I went to BYU, and I used everything,” he explains, “whether it has been writing, editing, background, or history. BYU gave me an understanding so that when my opportunities came, I was prepared to embrace them.”