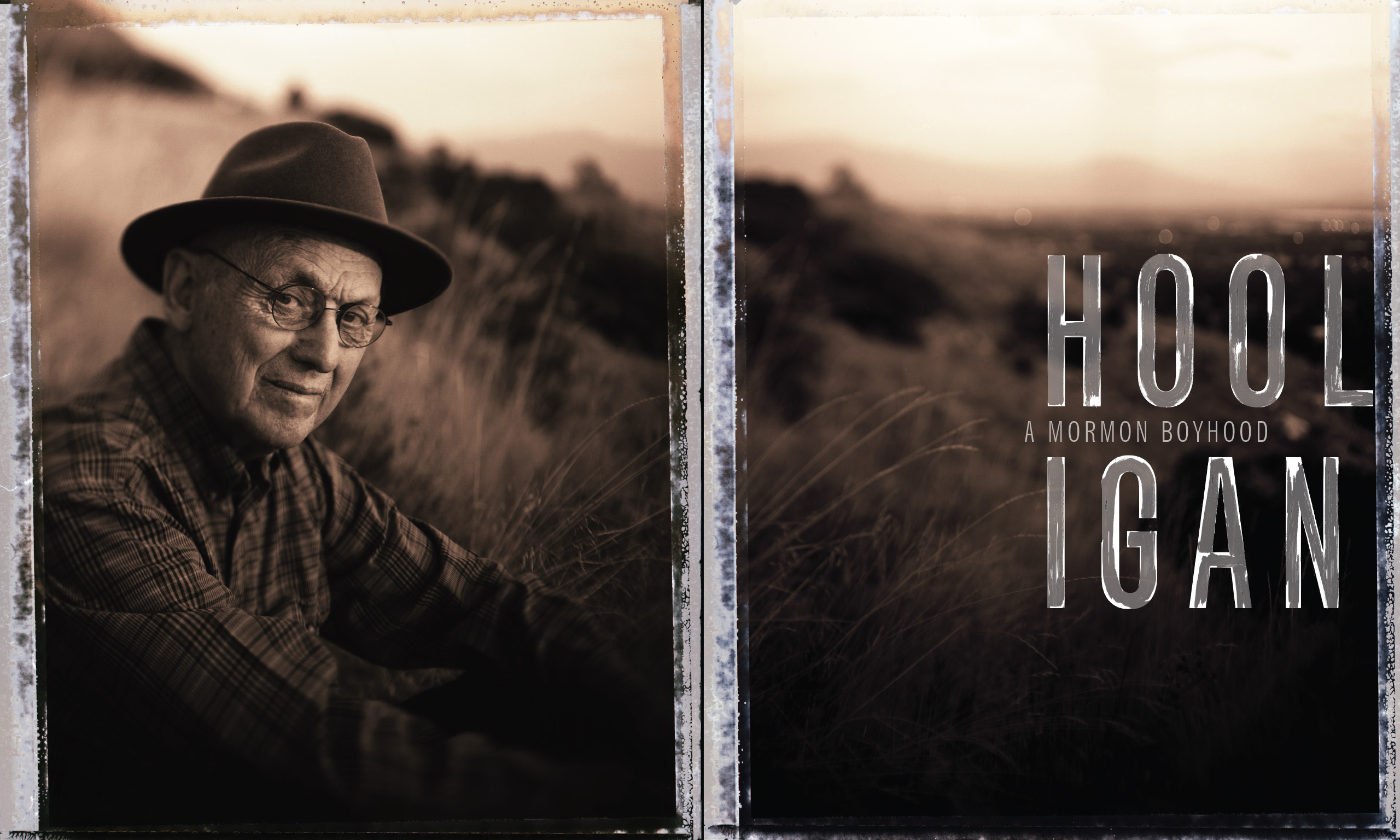

Hooligan: A Mormon Boyhood

By Douglas H. Thayer (BA ’55) in the Fall 2011 Issue

Photography by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

A sleepy Mormon town of 14,000 or 15,000, 1930s Provo was a splendid place to grow up for my friends and me. Our lives were mostly unattended once we were out of the house but still governed by the four seasons, school, geography, Mormonism, and family. Yet we were not aware of these intrusions. Nobody seemed to worry about us boys much, as if perhaps we weren’t of great value.

We were to be seen and not heard and were told that little pitchers had big ears; I never did figure out what that meant. Nobody was likely to steal one of us, and there were too few cars for there to be much danger of being run down, although we might die of polio or perhaps diphtheria, whooping cough, or gunshot, which took my friend Owen Hodson when he was 12 and classmate Reese Johnson at the same age.

The expression “to be taken,” which my mother used on occasion, always bothered me growing up. I couldn’t figure out who was taking him and where he was being taken and if he wanted to go, which I doubted, though perhaps it was something only faithful adult members of the Church understood.

It was important to be faithful. In 1920 my grandparents, Frederick and Nora Thatcher, and my mother, Lily, and nine other children, like so many other faithful Mormon converts, had heeded the call to leave Babylon and gather to the safe mountain valleys of Zion. Uncle T. Harry Heal, my grandmother’s brother, had come to Provo in 1906, to be followed by his brother James; his four sisters, Emma, Emily, Nora, and Laura; and finally their parents, my Great-grandfather and Great-grandmother Heal. Uncle Harry’s sister Henrietta had heeded the call to Zion earlier.

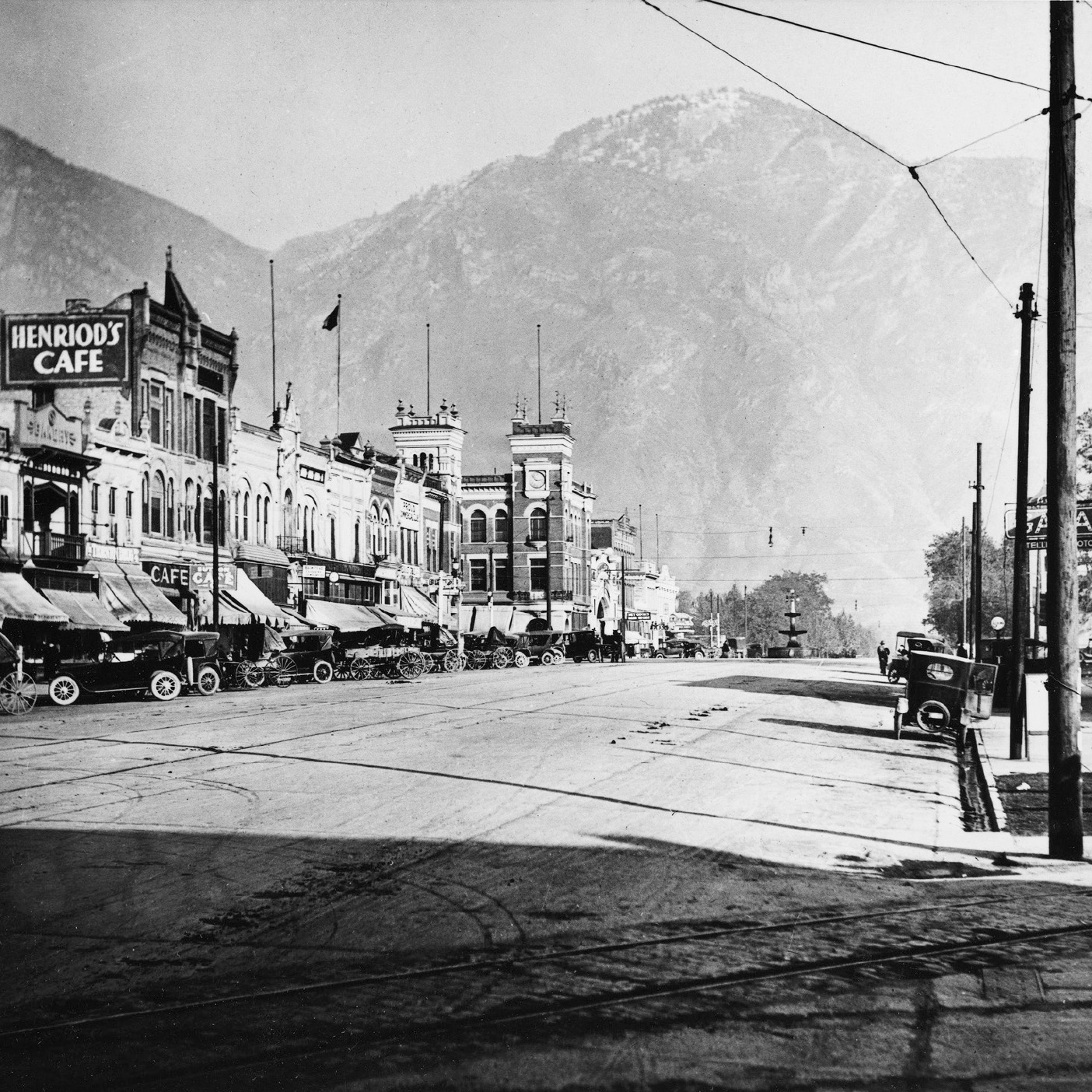

Settled in 1849 by pioneers, Provo was one of the towns south of Salt Lake City established by the Mormon prophet and colonizer Brigham Young. Ten or 15 miles stretched between each town, Highway 89 connecting them all—Lehi, American Fork, Pleasant Grove, Lindon, Orem, Provo, Springville, Spanish Fork, Payson, and Salem. The towns hugged the Wasatch Mountains because of the rivers and streams flowing out of the deep canyons. Water was essential for towns and the irrigated farms. Without water there was no life in a largely arid state seared by the desert sun.

Provo, the county seat and shopping mecca for the whole valley, had grown and prospered, particularly during the First World War and the 10 years after, but then the Depression came, and everything slowed down. Nothing seemed to change, and it wouldn’t until the beginning of the Second World War in 1939 and the coming of the Geneva Steel Plant and the 10,000 construction workers it would take to build it on the shores of Utah Lake, out of the range of Japanese bombers. Before that, there were few if any new houses or buildings going up, no new businesses or jobs, no people moving in or out, the neighborhoods static.

Like other early Mormon towns, Provo was laid out in square blocks with sidewalks and wide tree-lined streets, many still unpaved and providing a supply of ammunition for rock fights. University Avenue ran north-south and Center Street east-west, cutting Provo into four main sections, each with its schools. The kids in our section, the southwest, perhaps the poorest of the four, all went to the Franklin Elementary School, Dixon Junior High School, and then on to Provo High School with all the rest of the Provo kids. Except for an occasional farm, the foothills east of town were bare of houses and buildings. There was little traffic, with stop signs and stoplights necessary only on the most strategic corners and intersections.

The Mormons in Provo were divided into congregations by geographical divisions called wards—First, Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Wards, and so on, all the wards part of the Utah Stake, the only Provo stake. All Church members were brothers and sisters in the gospel, which is what you called each other even if you weren’t really brother or sister. And we boys identified ourselves in part by the ward we lived in. Each ward had its own chapel and often its own grocery store, which might be known by the name of the ward although it was not owned by the ward.

The Sixth Ward, where I and all my friends lived and—if we managed to stay on the straight and narrow path—attended Primary, Sunday School, priesthood meeting, and sacrament meeting, ran from University Avenue to Fifth West and from Center Street to the railroad yards and beyond. It was a big ward, a splendid place for roaming boys, its geographical area covering about 30 square blocks, if you didn’t count the fields and Mud Lake sloughs south of the railroad tracks. Highway 89, the state’s lifeline, cut through the Sixth Ward’s center on Third South.

It was the ward my Grandfather and Grandmother Thatcher had moved into when they made their 1920 exit from England. Granduncle Harry lived in the Sixth Ward, as did Grandaunts Emily and Henrietta. My mother’s brothers, Uncles Harold and Leonard, and her sister, Aunt Doris, lived there. It was our family ward.

None of my father’s family lived in the Sixth Ward. In fact, I never met any of his family, not even a distant cousin. Born in 1865, he was 35 years older than my mother, came from California as far as we knew, and was not a member of the only true church.

The postman, iceman, coalman, and milkman were a part of Sixth Ward daily life, a chip of ice out of the horse-drawn ice wagon a boy’s free summer treat, that and the soft sun-heated tar we dug up from the cracks in the road for gum, the embedded gravel keeping our teeth sharp. The pie lady pushed her converted baby buggy loaded with fresh homemade pies down the sidewalk calling, “Pies! Pies! Pies for supper!” A herd of milk cows came up Second West every morning on their way to pasture north of town by the brickyard and returned every evening, each cow turning voluntarily down its own lane. Twice daily the Heber Creeper, a small steam engine pulling its few cars, traveled the Denver and Rio Grande spur line up Second West to Provo Canyon and Heber Valley beyond.

During the Depression, Sixth Ward members were content if they could put food on the table, clothes on their backs, shoes on their feet, and a roof over their heads. We boys were often reminded in these hard times that we weren’t living in the lap of luxury. We knew what a lap was but had no acquaintance with luxury, so we couldn’t quite figure out what was meant. Our parents and other adults seemed to spend a great deal of time reminding us of things. We seemed to need a lot of reminding. We were frequently asked if our heads were screwed on right and told that our heads were like sieves and that whatever anyone said to us went in one ear and out the other.

Provo’s business district up and down Center Street formed the north boundary of the Sixth Ward, so it was easily accessible afoot or on bikes and was a place of great interest for us boys. The district ran along both sides of Center Street from First East to Fifth West and Pioneer Park, with blocks and half-blocks running north and south. Summers we were often in town, digging through trash bins, roving through Kress’ and Woolworth’s, the five-and-dime stores whose wares we could sometimes afford. We visited weekly Carlson’s, Stephen Bee’s, Guessford’s, and Sears, the best stores for sporting goods, where we bought our Red Ryder BB guns, BBs, and fishing stuff and later, when we were older, our .22s, shotguns, and deer rifles. We stopped to look into smoky, dimly lit pool halls and watched secretive men coming out of the state liquor store, keeping our eyes peeled, which boys were told to do. We picked up things from the counters and display cases, felt them, valuable things—bags of marbles, pocket knives, hunting knives, Big Little Books, heavy boxes of ammunition, fishing reels, and wristwatches.

From the Center Street business district, the whole town and mountain valley, a paradise for roaming Sixth Ward boys, spread before us.

On the corner of University Avenue and Center Street was the Utah Stake Tabernacle built by the pioneers, and next to that the Orem interurban station, and across University Avenue the white classic Greek–looking city and county building, and on the corner the city building with the police station in the basement. We boys heard stories about older boys arrested, handcuffed, being dragged down those stairs to their imprisonment and doom.

North from Center Street up University Avenue five blocks was the Brigham Young University Lower Campus and beyond that, on Temple Hill, the Upper Campus. Farther out was the brickyard, the millrace, farms and orchards, and the Provo River, where we swam naked and free. Across the river and up on the bench was Orem, with its thin two-mile-long business district and its vast apple, peach, cherry, and pear orchards, where a boy could work his fingers to the bone picking cherries at 3 cents a pound—peaches, apples, and pears yet too heavy for us to carry in the big canvas picking bags.

Farther west from Provo were fields and then Utah Lake, into which all the valley towns dumped their untreated sewage, the lake a great place for swimming, killing carp, creating sand cities, and building log rafts to float away on, never to return.

The close, surrounding mountains gave everything a feeling of permanence, even isolation, as if nothing could enter or leave Utah Valley. The Utah valleys were Zion, a place of protection and safety. Out of Utah and beyond the mountains, as we boys had been told so often in church, lay the harlot Babylon, with all her enticements, which we, at the risk of our eternal salvation, must avoid, although there seemed little chance of being enticed at the time. Though we might hike 10 miles in a day or bike 20 or even 30, we weren’t likely to go too far astray. Of course, there was always the possibility of thumbing a ride or hopping a slow freight to faraway places.

With one father in three out of work, WPA crews digging water-line and sewer trenches in the streets, and federal-relief checks and commodity handouts and Church welfare the only salvation, ambition seemed somewhat unrewarding, even excessive. Our greatest desire was to turn 16, be licensed to drive and to hunt deer, and then at 18 graduate from high school, never have to go to school anymore in our whole lives, and join the Army and go to war. A high school graduate might expect to go to college, if his family had money, but few families did.

No one seemed ambitious for us. We were not often urged to compete, to rise in the world, because there wasn’t much for a boy to rise to, except perhaps to the status of an Eagle Scout. It was hoped that someday we might get a job and be able to pay bills. Being able to pay your bills was very important. On the radio at nights, listening with our parents, we heard the Hindenberg go down, heard War of the Worlds, and heard President Roosevelt reassuring the whole Depression-defeated nation that they had nothing to fear but fear itself, later seeing these events in Life magazine’s black-and-white pictures and in Movietone News films. Adequately fed, clothed, housed, largely free, seekers of our own pleasures, we boys were not afraid. The approaching world war only intrigued us, filled us with the hope of eventually being old enough to join the military and fight.

Hiking in the east mountains, far above Provo on summer days, five or six of us together, we sat on high ledges, drank from canteens, and looked down at our familiar town, if there was a breeze. Otherwise, the smoke from the coal stoves, Ironton, the pipe plant, and railroad yards obscured the view, sometimes covering the valley in a layer of smoke. But on clear days we saw the small towns, each a cluster of dark trees, connected by Highway 89, and the band of dark trees along the river, the shimmering polluted lake, the west mountains beyond, the patchwork fields, railroad yards, BYU, downtown, the high brick smokestack from the burned and destroyed Woolen Mills, and the 30 or so square blocks of the Sixth Ward, the yellow-brick ward house visible among the trees.

And yet in our heart of hearts we wished that the pioneers had never come, that the valley lay as it had for centuries, populated only by Indians, smoke drifting up from their villages, their teepees pale in the afternoon sunlight. We wanted to see herds of buffalo, antelope, elk, and deer, see mountain lions and the solitary and dangerous grizzly bear and packs of wolves. We wanted to be hunters and warriors, wear loincloths, carry bows, quivers filled with arrows, and lances with long obsidian points, or at least be mountain men and trappers dressed in buckskin and wearing coonskin hats and carrying our muzzle-loading rifles across our saddle horns—ever wary of Indian attack—or, barring that, be cowboys wearing two holstered ivory-handled pistols and riding splendid white horses.

Yet, sitting on our ledge, looking down, pleased but not knowing why, we were glad that we lived there in this place and in this time. For, whatever adults may have thought, the Sixth Ward, Provo, and Utah Valley belonged to us boys, all of it accessible to us because we were largely free to roam as we pleased, as long as the police, sheriff, and truant officer didn’t haul us in and we didn’t maim or kill ourselves or each other, or otherwise interfere with adults and their dreary lives.

Sixth Ward yards, running to the middle of the block or abutting one another, with lawn or not, were all fenced in, and, depending on the owner’s seriousness, at different heights with various combinations of barbed, sheep, and chicken wire and boards. We boys knew which fences were climbable and where, vital information when trying to escape a neighbor’s wrath or elude an enemy’s pursuit. As each yard was named after the owner, a boy referred to the Oldroyds’ yard, or the Madsens’, Claytons’, Tuckers’, Menloves’, or Grays’. Yard boundaries were strictly kept, not unlike the way the Mormon faith required observable limits.

We knew who would shout at us and order us away: “You kids get out of here! I’m calling your mothers! I know who you are, and don’t think I don’t!” Or the more dire threat: “I’m calling the police right now! I’ve warned you before. I’m not putting up with this hooliganism any longer!”

Adults often asked what we were up to, as if our intention was always devious. We were called little devils, scallywags, hellers, born hellers—which was worse than a plain heller somehow—or hooligans. Hooligan had a nice sound. I didn’t mind being called a hooligan.

Engaged in our various pleasurable roaming activities, we boys did not wear or need watches. We told time by the sun, by how hungry we were, by the Troy Laundry noon whistle, and by the Heber Creeper coming back in the afternoon. The Troy Laundry whistle blew every day at noon. You could hear it all over town, so you knew it was noon. If you were late getting home for lunch or something, your mother would ask you if you had heard the whistle and why you didn’t pay attention. But time wasn’t important for us boys. Not caring about a past or a future, with no memory or anticipation, we lived only in the present moment.

By the time we were 12 and 13, beginning the seventh grade at the Dixon and as new Boy Scouts and deacons, we boys needed more room. The Sixth Ward neighborhood wasn’t big enough, our activities there had become somewhat childish, our lives more serious.

We rode our bikes up to Temple Hill to wander through the four buildings on the upper BYU campus—Maeser, Grant, Joseph Smith, and Brimhall. The Brimhall was the most interesting, smelling strangely of laboratories. The walled-off corner of one room held snakes (including rattlesnakes), lizards, and Gila monsters. We liked it when the rattlers buzzed. We thought the worst death would be to fall into a pit of rattlers.

In one room of the Brimhall Building was a high shelf of large bottles holding human fetuses arranged in various stages of development. Hushed, we looked up at these a long time. We knew this was serious, important, and instructional, but we didn’t know exactly why. We knew women got pregnant somehow and had babies, and this was what the babies looked like before they were born, but you had to have a spirit inside of you to stay alive, which these didn’t. It was very important to keep your spirit inside you and not let it get away.

The doors to the rooms were always open. The building seemed almost empty; by this time the war had begun, and there were few students. If a professor came by, he was not suspicious. He said hello. We were treated not as the hooligans we were but as fellow seekers after knowledge. The Lower Campus had a big room with dinosaur skeletons and a diorama with a tiger and a crocodile, but they weren’t as interesting as the rattler pit and the shelf of bottled fetuses.

Older now, we stopped swimming in the public North Park pool in the cold, chlorinated water, where you had to wear trunks and the lifeguard was always hollering and blowing his whistle. We preferred swimming naked in the river.

Forty yards wide, maybe 50 long, 15 to 20 feet deep, the Crusher was the best swimming hole on the lower river. We swam and swam, stayed in the water, dived, wrestled, played tag, had water fights, and then, when we tired, floated on the logs that had come down with the spring high water and had gotten caught. We fought for the best logs, pushing each other off, tipping the logs, until finally maybe two or three of us floated on one log.

Absorbing the heat, paddling just enough to stay out in the middle, we lay facedown, our hands in the water, our bodies having burned and peeled so often that we were as brown as Indians. Lying forward, you wrapped your arms around the log, and, nose touching the water, looked down into the depths. Carp, suckers, minnows, and trout swam there. Slipping off the log, we sank down to be with them, tried to be fish.

After supper we played night games in the summer street—mainly hide and seek, pom-pom-pullaway, red rover, annie-ay-over, gray wolf, and kick the can. Girls played with us; we did not object. Sometimes it was even interesting to stand around talking to girls. Fathers came out to water the front lawns with hoses; our mothers sat in chairs on front porches to catch the breeze or walked next door or across the street to talk to a neighbor.

At 10 o’clock we were called in to go to bed, unless we had a sleepover, fathers and mothers or older brothers and sisters shouting our names from the front porch or sidewalk until we acknowledged we were still alive, but quietly.

“I’m coming. Good grief, Mom. Can’t I play for just 10 more minutes?”

“You’ve played enough. Tomorrow’s another day.”

“Gee.”

If we slept over, it was usually on a friend’s back lawn or in a tent put up for the occasion, not in the house, where there was really little place, for we did not have bedrooms of our own. Later, the neighborhood fast asleep, the shadows dark, we dared each other to run around the block in our shorts, in the end all of us taking turns. You ran barefooted, hiding behind hedges, fences, trees, and rosebushes if a car came down the street, terrified that a cop might reach out and grab you and put you in jail.

And then, warm under our blankets, not knowing exactly when it happened, we fell asleep to the sound of crickets and the far-off lonesome wail of a train going through Provo to some faraway and distant place.

A Provo Boy

When Douglas H. Thayer (BA ’55) began his official association with BYU, he was a student at BY High, and Franklin S. Harris (BS 1907) was the president of the university. It was 1944, and Thayer soon found himself sitting next to GIs who had returned from World War II and enrolled at BYU but who needed to complete a few high school courses.

Back then, BYU was divided into upper and lower campuses, with a swift stream of students flowing up and down during class breaks. “You had to make it in 10 minutes, which was impossible,” Thayer recalls. The divided campus, however, remains only in memory, and Thayer says students from those postwar days would not see much that was familiar on campus today. “About the only thing you’d recognize is the Maeser Building, the Grant Building, and the Brimhall Building. The rest of it is new. I watched it all happen.”

Indeed, Thayer has been an eyewitness to decades of BYU’s development. Between 1944 and 1955—with breaks for military service and a mission—he was a student at the high school and then the university. After graduate work, he returned in 1957 to join the English faculty, where he remained for 54 years until his retirement in 2011.

Thayer’s scholarly pursuit was creative writing, and he published six books—three novels, two collections of short stories, and one memoir. The essay published here is excerpted and adapted from his memoir, Hooligan: A Mormon Boyhood (ZarahemlaBooks.com, 2007). A new collection of his short stories, Brother Melrose and Other Stories, will be published by Zarahemla Books this fall. With a novel and more books yet in the works, Thayer says he is driven to write “because a long time ago I decided that if I didn’t, when I got to this stage of life I would regret not having written.”

—Jeffrey S. McClellan (BA ’94)