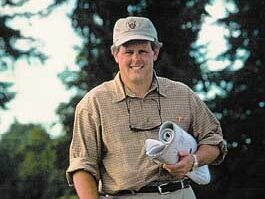

Kevin Towers le ans forward anxiously. Sitting behind home plate at Dodger Stadium, the San Diego Padres general manager is sweating out the ninth inning.

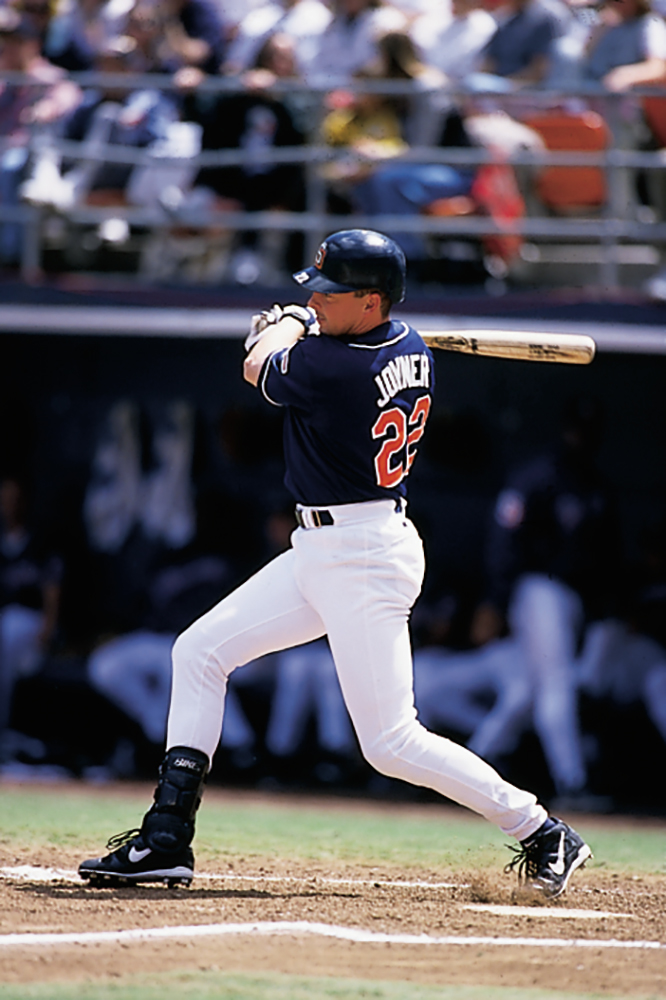

The Padres trail, 3-2, but have a runner at second. Batter Wally Joyner smashes a one-hopper to deep shortstop for a hit, putting runners on first and second with one out. But the next two batters fly out, and the Padres lose.

The late-season defeat is unusual for the 1982 BYU teammates, Towers and first-baseman Joyner.

Since Towers arranged a December 1995 trade to acquire his longtime friend, San Diego has won two National League West Division titles–1996 and 1998. Between the championships, the 1997 Padres finished last, 14 games behind first-place San Francisco. But San Diego rebounded in 1998 with a franchise record 98 wins, a 22-game improvement. The Padres went on in 1998 to polish off Houston and Atlanta before reaching the World Series (the first time since 1984), where they fell to one of the most powerful New York Yankees teams ever.

The successful 1998 season was stimulated by the tall, burly Towers, who revamped San Diego’s pitching staff. Towers traded for ace starter Kevin Brown (18-7) and acquired four veteran relief pitchers. The hurlers helped lower the staff’s earned run average from 4.99 last year to 3.64 this season.

Towers’ astute moves have earned him wide praise.

“Kevin Towers did a fantastic job,” says Tom Lasorda, former Dodgers manager and interim general manager. “He really knows how to build a team. He has the right people working for him, he knows who he can rely on, and he knows how to wheel and deal. Towers made some outstanding trades.”

Joyner made Towers’ earlier trade look good this year by hitting .298 with 12 homers and 80 runs batted in. He batted .412 with runners in scoring position, second in the major leagues, and made only seven errors in 1,073 fielding chances, a .993 percentage. The numbers burnished Joyner’s already shiny credentials. He’s hit .292 while averaging 15 home runs and 78 runs batted in over 13 major league seasons. His .994 fielding percentage ranks fourth among first basemen who’ve played 1,500 games.

Of course, Towers knew those credentials when he acquired the articulate, winsome Joyner.

“He’s a terrific player,” says Towers. “He’s a leader in the clubhouse and a terrific defensive first baseman. He’s among the top hitters in the league with runners in scoring position. We’re a completely different team when he’s not playing.”

At the end of the season, Towers had a chance to demonstrate Joyner’s importance as the 6-foot-2, 200-pound first baseman, 36, became eligible for free agency.

Joyner, however, seemed to make negotiations easy. He was so open about his desires to stay in San Diego that he punctured the stereotype of the greedy player only out for himself.

“I’ll take whatever they’d like to sign me for,” he said while ducking in and out of the batting cage at Dodger Stadium. “I’ve had a great career. Now, the longer I can play, the better for me.”

Joyner, his wife, Lesley, and their four daughters love San Diego and, after leaving Anaheim in 1992 and Kansas City in 1996, are tired of relocating. Joyner also wanted to stay because he enjoys playing on a winning team, said his agent, Barry Axelrod.

To their credit, the Padres didn’t take advantage of Joyner’s willingness to stick around. The Los Angeles Times reported on Oct. 29 that the club signed Joyner to a two-year, $6.7 million contract with an option for a third year.

With Joyner the Padres will continue to benefit not only from one of the best first basemen in the majors but also from Joyner’s sense of humor. A member of the LDS Church, Joyner, of course, doesn’t drink, chew tobacco, or cuss. But he does perpetrate pranks.

“If you use humor properly,” he says, “it adds to the chemistry and unity of a team.”

In the name of team chemistry Joyner once ordered 20 drinks and 28 ice cream sundaes in a team hotel, according to the San Diego Union-Tribune, and signed the bill for a few hundred dollars in Towers’ name. When Towers argued the bill while checking out of the hotel, players around the lobby chuckled.

Joyner pulled his best prank in the late 1980s with the California Angels in Texas.

“We had a night game before a day game,” he says, “and it was unbelievable the amount of locusts falling out of the sky. You couldn’t go anywhere without stepping on them.

“The next day I came out to the dugout and all the locusts were in the corner trying to stay out of the daylight. I saw a new bag of chewing tobacco someone had left. I filled it with live crickets and threw it on the bench.

“About the seventh inning Bill Buckner was getting ready to pinch hit. Concentrating hard, he put his hand deep in the bag to get a big handful of chew, and the crickets crawled all over his arms.

“He put his hand up to his mouth and saw nothing but eyes looking at him. Then he threw his hands up. The crickets went flying–and he went flying, running out of the dugout, jumping, almost to the coach’s box.

“This was while the game was going on. That was probably my best ‘gotcha.'”

Joyner’s humor was noticeable to Towers even when the two met in 1981.

“Even then, he never had a bad day,” Towers says. “The times you felt down, he would lift you up.”

Towers came to BYU after pitching two years in a San Diego junior college and attending high school in Medford, Ore. Joyner arrived as the Georgia high school player of the year.

Despite different backgrounds, Towers says, “We developed a strong friendship.”

In 1982, his only season at BYU, Towers finished with a 4-4 record, but the Padres drafted him and he pitched seven seasons in their farm system. Joyner was taken by the California Angels in 1983, his junior year, after hitting a lusty .462, and he reached the major leagues in 1986.

Although the two players had gone separate ways, they remained friends. “We used to run into each other at spring training,” Towers says. “We’d get a bite to eat together. I enjoyed watching his career.”

When a series of arm operations ended Towers’ career at the AAA level in 1989, the Padres rushed to make him part of management.

“Every year I would talk to the Padres about Kevin’s coming back from injury,” Axelrod says. “Their minor league director always said, ‘You make sure that Kevin knows that when he’s done playing, we want to hire him.’ They recognized very early that he was bright, dedicated, hard working, and knew and loved the game.”

Towers saw the Padres interest “as an opportunity to get into scouting and remain in the game that I loved.”

He served as a Padres scout from 198991, worked for the Pittsburgh Pirates for two years, and returned to the Padres in 1993 as scouting director.

In 1995 he was helping club president Larry Lucchino interview outsiders for the general manager’s job when Lucchino decided his man was Towers, then 34 years old.

“I didn’t even know I was being considered,” Towers says. “It took me by surprise.”

“Kevin is a real baseball guy,” says Lucchino. “He’s a great evaluator of talent, and he has a very strong work ethic. We knew he’d grow into the job and become a prototype of the modern-day general manager.”

Lucchino looked like a prophet after the Padres reached the World Series with players secured by Towers. Although Towers didn’t like the series results, the Yankees won his respect, sweeping the series 4-0.

Still, most of the 65,000-plus fans stayed around after the final game to applaud their Padres, who came back out on the field for a curtain call.

“We got close,” said Joyner over the PA system. “It was special because of you.” As Joyner scooped up a handful of dirt off the mound, it became clear that there’s still hope that he, Towers, and the rest of the Padres will find the pay dirt again next season.

Gary Libman, a freelance writer living in Los Angeles, is a former reporter for the Los Angeles Times and a former executive sports editor for the Minneapolis Tribune.