By Dean W. Duncan, ’87

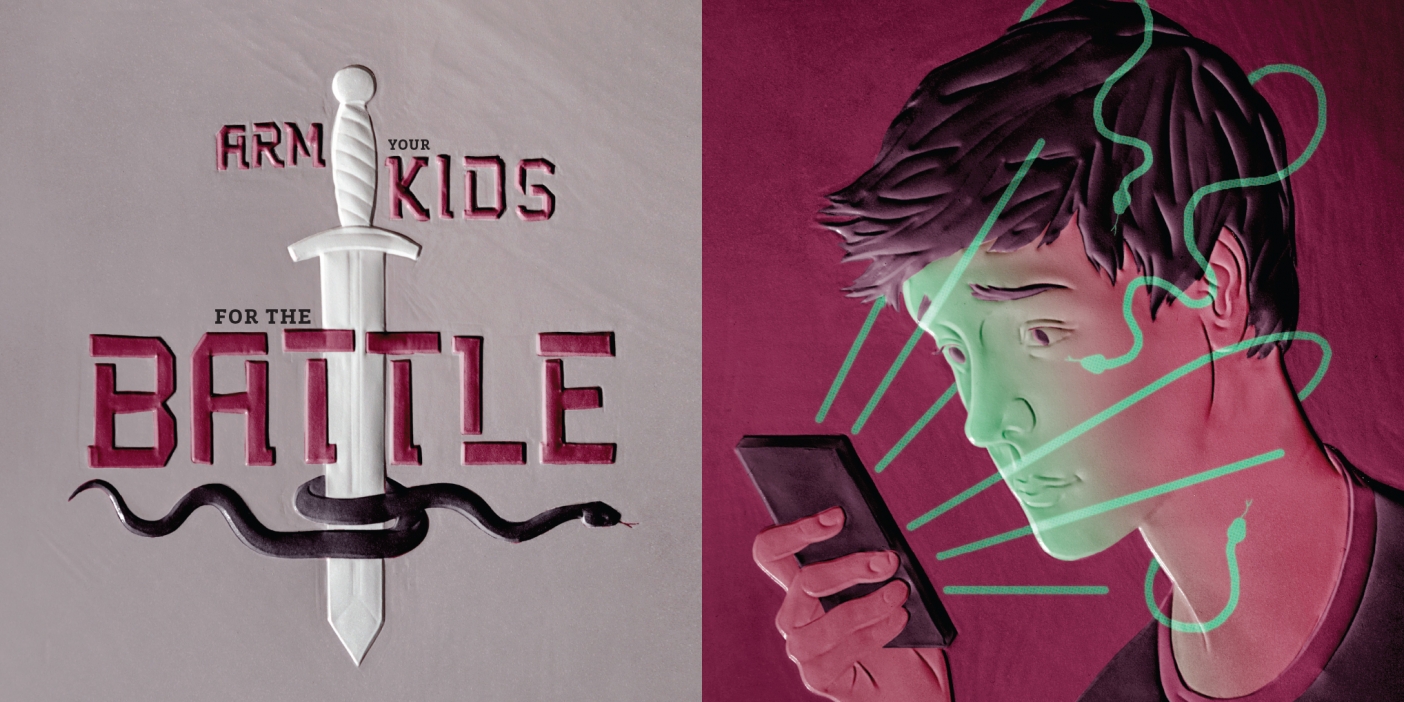

FOR most families, media presentations—stories and ideas disseminated through movies, radio, television, computer games, and the Internet—are a major part of everyday life and a major source of everyday concern. Media can provide wonderful information and entertainment. Unfortunately, they can also have many negative elements and pernicious effects.

LDS Church leaders have repeatedly encouraged us to steer clear of inappropriate media. Yet with every new television season, it seems that the negatives are more and more evident and more and more difficult to avoid.

It is possible, though, to use media in our homes in a positive way. In fact, I submit that we can gain much from media. Many people claim that there is not much good, wholesome, uplifting material for families. Not true. Far from there being a once-in-a-while trickle of safe things, I have found that there’s more of good than we can ever get to. And a few healthy practices—such as the following seven points—can help us not only to enjoy media in our homes but to turn our media choices to substantial edification.

Fundamentals

One of the first steps to gaining more from media is to turn off your TV—at least for now. Some of us have negative patterns of media choice and consumption. If we are to effect media reform in our homes, we need to tune out long enough to think about some better alternatives, to relearn some fundamentals. One of the most basic of these is that media and all of their technological bells and whistles are simply tools and techniques. The first thing is story.

This notion may seem strange to those who are inclined to think of stories, or the arts in general, as mere recreations or vehicles for escape. Within the confines of that argument, they have a point; consumer art—or art consumed—might as well be left alone. But art as proxy, art that tells us about real things and helps us pass abundantly through them, is practically a necessity. We need narratives and the perspective they bring.

Hence, a good second step to media reform is to dust off your library card and reintroduce yourself to books—and to the world of children’s literature in particular. As you enter this world, you may find a number of surprising things. One is that your children will be delighted with your company there or, if they’re not readers yet, that they will follow your example. Another is that you won’t be just feigning interest in childish things. The open-minded, open-hearted adult will soon find herself fully engaged in this marvelous, practically inexhaustible material.

And as you read you’ll find that dews will distill and that you will become sensitive to nuances of story and character and narrative and style—things that you’ll also find on TV and at the movie theater. As you boot back up and plug back in, you may discover that literature and media are not so different after all.

Supervision and Appropriateness

There are near infinities of appropriate media for the family, and yet sometimes we feel like we can’t see around the bad stuff. There is a solution. Clean house. Upgrade your own habits. Then, as much as possible, do not allow your children—particularly the little ones—to be exposed to anything you have not approved. All this supervising requires time and vigilance, but there are benefits: it’s fun!

In giving approval, however, we all need to recognize that there is more to appropriate media practice than merely avoiding representations of sex and violence and the use of coarse language. We must understand that seemingly innocuous material can also have a negative effect on impressionable children—and on the rest of us as well. Materialism, cults of celebrity and popularity, celebrations of impertinence and self-absorption, even plain tackiness—all are rampant in our media, and they are too often presented and received uncritically. These things can distract and even harm us nearly as much as the more obvious, more discussed media transgressions.

Active Reading

Whether or not media have a positive effect in our lives has much to do with our own preparation and effort. The best program won’t help a passive, self-absorbed viewer very much; on the other hand an active, intelligent, interrogating reader can turn most all of her careful media choices to happiness. “Active reading” means we don’t just absorb a text—be it written, spoken, or acted—through our senses. We also analyze and discuss the ideas, themes, and images, thereby turning entertainment into education.

For instance, in The Lion King, Timon and Pumba present the hero, Simba, with a very attractive alternative to the slings and arrows of anxious engagement. Who hasn’t wanted, like Simba and his friends, to escape life’s difficulties? But hakuna matata makes escape a philosophy of living and is very inappropriate, in a sins-of-omission sense. Simba comes to see that, and so can we. As we talk through ideas and consequences with our children, we can teach important life skills.

The same is true with other presentations. When a movie or television show or computer game presents your family with ideas or images with which you disagree, talk about it. An open discussion of these presentations can help to inoculate against harm. Simple conversation can expose the problem and begin to turn it to our own instruction.

Moderation

As PlayStation addicts and their parents (or children) know, it’s easy to get carried away with media. Resist. Keep surfing to a bare minimum. Have a purpose when you turn on that machine. Having accomplished that purpose, turn the machine off. Be very selective about weeknight or Sabbath usage. Keep TVs out of kitchens and bedrooms. If our media don’t add to our sense of connection and community, they’ve ceased to serve us.

Location and Decorum

Seeing loud movies in dark theatres may be fun, but the popcorn-chomping passivity that these settings foster is not generally conducive to education. I’m convinced that the best place to watch and read and talk media is in the home, where classroom curiosity and discussion can be encouraged.

Talking out loud is, quite properly, discouraged at the movies, but talking—asking questions and getting answers—is one way children learn. TV programs and films should be read aloud, like a picture book. Parents should provide running commentary, discussing story and character, theme and meaning, image and sound; they should rewind and repeat and ask leading questions. This approach makes impossible the open-mouthed, empty-eyed gaping usually associated with TV babysitting. And in modeling such active reading, we insure that our children will become informed and literate.

Variation

In the spirit of balanced diets, we should watch what we consume in the media and seek variety. Learn about media categories and moderately pursue them all. There are games and stories of adventure and escape, sermons and fables, folk and fairy tales, realistic fiction, silent and international films, scientific and historical and informational media, and on and on. There’s enough in this ensemble of approaches and subjects to fill all the years we have with our children—and to occupy all the grandchildren as well.

Duration and Extension

The logical end to proxy experiences is that we return to our lives instructed and invigorated, ready to try harder and do better. We should always remember that books and media are means to that end. Standard-length films and many television programs (not to mention aimless Internet surfing) do not leave us enough time to discuss, let alone to apply. So consider installments or shorter programs and remember one of the best and most basic of teaching ideas: extension.

The idea of extension relates to the media moguls’ concept of the ancillary: Not only do they sell us the game or movie or TV show, but they also offer toys and novelizations, even underwear. This idea, so dangerous to your checking account, is really native to the classroom, and it belongs in the family room. It means that you never just watch a video, since the closing credits are just the start of a process. After the movie, read a story and a scripture, build a model, play a game, write a letter, make a visit.

For example, last fall some of our little ones were reading “The Surprise” from Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad All Year. In this lovely story two friends try, with pure intent and little success, to help each other with some seasonal cleanup. After we closed the book, we went outside and raked leaves and talked about service and secret sharing, about plans that go awry, and about the satisfaction of even making an effort.

It is the combination and accumulation of activities on a theme that make active, informed, edified media consumers. More important, these activity clusters mean that, in part through media, we’re constantly learning together and enjoying one another. Moreover, parents and children become bound by common experience, common principles, common strivings, and mutual accomplishments.

Yes, there is much that is inappropriate and even dangerous in media, and we should steer carefully around such things. But we should also beware of our own habit of keying on the negative and ignoring everything else. That everything else is that the new technologies, as well as the old truths they present, are heaven-sent boons and blessings, sources for joy, and causes for gratitude. If you are not convinced, the means of proving it are within your reach. Give it a try.

MORE: For a few specific media suggestions, please see our Web site at magazine.byu.edu/extras.

DEAN DUNCAN, a BYU assistant professor of theatre and media arts, emphasizes film history, theory, and criticism and teaches a class on children’s media.