Symbiotic Pathways to Truth

Choose faith until you better understand science—or until science can provide better explanations.

By Jamie Haslam Jensen (BS ’99, MS ’03) in the Winter 2021 Issue

Illustrations by Simon Pemberton

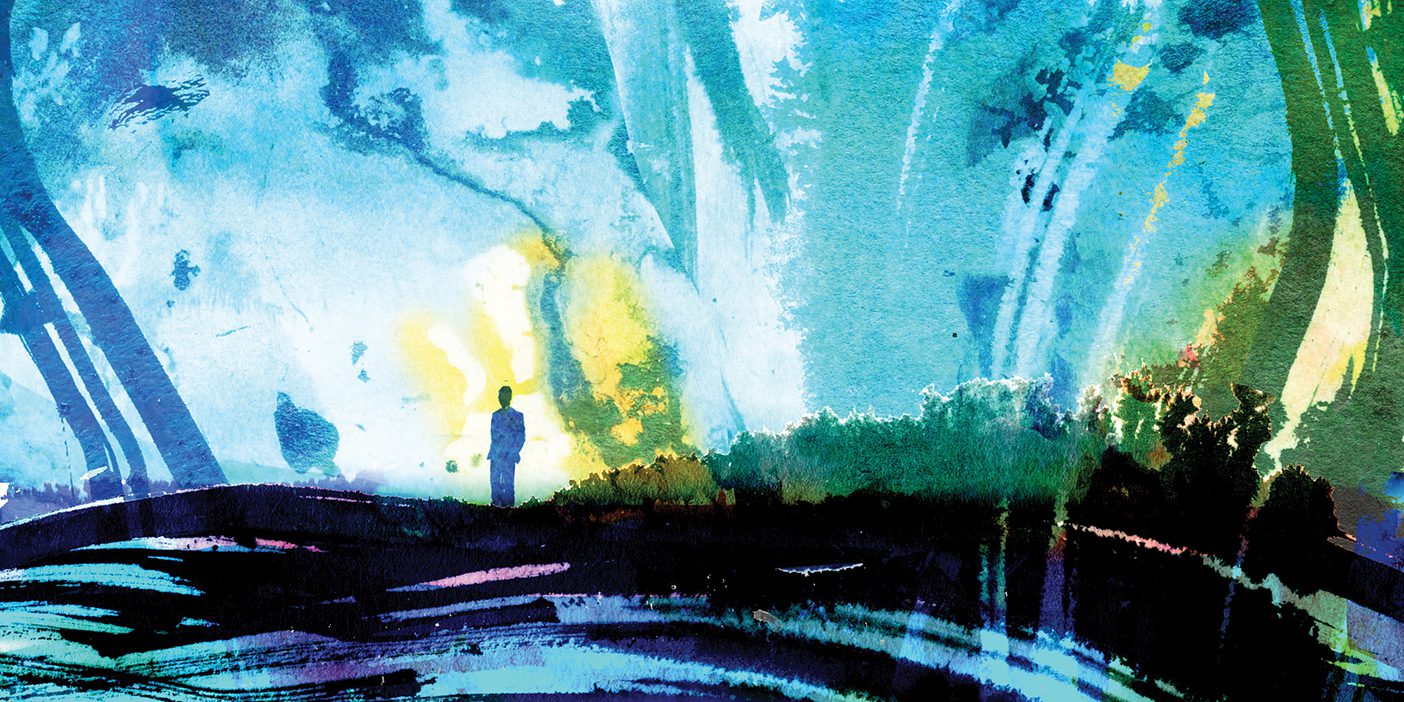

A battle has been raging for centuries, a battle between faith and science, a conflict that is tragic and completely unnecessary. It is a false dichotomy. Truths found through faith in the Lord Jesus Christ and obedience to His commandments and truths found through the diligent study of His scientific processes here on Earth can combine into a beautiful blessing of knowledge that can enhance our lives, save our children, bless our Earth, and help us return back to our heavenly home with the blessings of exaltation.

Symbiosis is a term we use in biology to indicate an interaction between two different organisms living together in a dependent and often beneficial relationship. Likewise, faith and science should live symbiotically in our hearts and in our minds as we search for truth in our lives.

Finding Truth with Science

As a scientist, I find joy and wonder in the beauty of logic and evidence and all things analytical. Let me share the beauty I see with you.

Science is a process through which we gather evidence from the natural world to find explanations for natural phenomena. Physicist Pierre Hohenberg explains that “[Big-S] Science emerges from [little-s] science” as “collective, public knowledge . . . universal and free of contradiction” but only after repeated confirmation by independent, robust investigations.¹ Often, we get caught up in the little-s science and impatiently reject a scientific idea simply because it is in its infancy and may seemingly contradict what we think we know from a religious standpoint. Other times, we foolishly reject big-S Science because we don’t fully understand how it plays in harmony with our religious beliefs. Both are errors born of impatience.

As scientists, we are in search of the truth, but we have to work with the tools and evidence available to us. So we make hypotheses about the natural world, and we test them by gathering data.

Truth Is in the Bag

To illustrate the process of science, a group of students are given a Lego-brick structure—an object that represents the truth—inside an opaque bag. They are instructed to re-create the structure with other Lego bricks by feel alone, without looking in the bag. As a metaphor for the process of science, scientists would reach in the bag, feel, take measurements, and gather all available data. They would then collaborate with fellow scientists who have performed similar experiments and collectively decide on the conclusions most supported by the data. After testing and confirming many related hypotheses, they would form an overall structure of the truth, a structure that incorporates the many different hypotheses. We call this explanatory structure a “theory,” or the best and most well-supported explanation we have based on the best evidence we can gather.

If I were to ask those students, after they had worked on their structures for an hour and collaborated with each other, “How sure are you that you’ve got the structure right?” they would all answer that they were completely sure, or at least 99.9 percent. However, if I asked them how sure they were of the color of the pieces, they would answer, “Not sure at all.” So there are aspects of theories that we haven’t quite worked out yet.

In the case of the Legos, I gave students the stipulation that they could not look in the bag. If we were talking about the evolution of the diversity of life, for example, we can’t go back in time and see it occur. We can’t ever “look in the bag.” So there are some things about the process that we may not ever know. But we can see the evidences of what occurred all around us. In the case of Lego color, the students couldn’t figure it out given the current equipment and stipulations I gave them. But perhaps in the future we will invent an infrared device that can shine on the Lego pieces in the bag and illuminate their colors without us actually looking at them.

So it is possible that we will get a more complete understanding of the truth as science advances and we are able to gather more data. But for now, we can feel pretty assured that we have got the structure down, even if we are unsure of the colors. And we can trust that scientists will continue studying the nuanced details of these theories to try to get closer and closer to absolute truth. How sure are we of scientific theories? Pretty darn sure.

Defining the Nature of Faith

Seeking religious truths is an entirely different epistemology, but it is not entirely different in the process. The main difference is in the evidence. When I was in graduate school, my major professor often challenged me about my belief in God and how I could possibly reconcile it with the science I was studying. He was clearly not a believer. I argued that the God hypothesis is not testable through scientific means. He argued that it was testable and that the evidence clearly showed that God does not exist. He claimed that religious people accept without evidence and would even ignore the evidence against God if it were presented to them.

I answered back that although I was religious, I was not one who accepts without evidence. When I was 17, I decided to find out for myself if God was real. Since that time, I have been convinced again and again, by evidence, that God does, in fact, exist. Unfortunately, the type of evidence I have to offer is mine, and mine alone. It is not the type of evidence that I can share with anyone else because it is based on intense, undeniable feelings as well as personal experiences that wouldn’t mean the same thing if I explained them to someone else. However, I have performed tests.

Let’s take a simple example in the Book of Mormon. At the end of the book, Moroni offered us a test. He said:

Behold, I would exhort you that when ye shall read these things, if it be wisdom in God that ye should read them, . . .

. . . that ye would ask God, the Eternal Father, in the name of Christ, if these things are not true; and if ye shall ask with a sincere heart, with real intent, having faith in Christ, he will manifest the truth of it unto you, by the power of the Holy Ghost.

And by the power of the Holy Ghost ye may know the truth of all things. [Moro. 10:3–5]

So here is a clear test with a clear prediction:

• Test: Ask God.

• Prediction: If this record is true (my proposed hypothesis) and I ask God (my experiment is to pray about it), then I will be given confirmation by the Holy Ghost (the evidence).

Here is where the processes differ: the evidence here is different. It is not tangible, measurable evidence by a scientific definition, but it is real evidence nonetheless. However, this test assumes that you know how to recognize the Holy Ghost and the evidence—in other words, that you have the necessary tools to detect the evidence. These spiritual tools take practice to develop, but they do exist and you can develop them. In terms of science, there is nowhere that this type of hypothesis testing fits in. However, this is not to say that this spiritual hypothesis testing is in any way less valid. It is just a different way of approaching truth.

“Hold off judgment, be patient, and keep an open mind to truth from both sides.” —Jamie Jensen

Interestingly, my professor’s response to this was, “Thanks for sharing. I think you have made your case very clear. As I think you said, your type of [spiritual] evidence cannot count as scientific evidence. Recall that replication by others is a key. Can others replicate your test and get the same results (which must be open for all to see)? If not, then it does not count.”

I didn’t respond to this, but I should have responded with, “Absolutely! And I’ll teach you how!” What a wonderful missionary opportunity I missed. This test is absolutely, 100 percent repeatable, and everyone can receive the spiritual evidence if they choose to develop the spiritual tools necessary to detect that evidence.

Comfort with Uncertainty

In our world today, dogmatism abounds in politics, religion, and science. Dogmatism is “the tendency to lay down principles as incontrovertibly true, without consideration of evidence or the opinion of others.”² In science there is a growing extremism, called scientism, that claims that science is the only source of knowledge and any pursuit outside of that is fantasy.

Dr. Thomas Burnett, a philosopher and science historian, aptly put it this way:

It is one thing to celebrate science for its achievements and remarkable ability to explain a wide variety of phenomena in the natural world. But to claim there is nothing knowable outside the scope of science would be similar to a successful fisherman saying that whatever he can’t catch in his nets does not exist. Once you accept that science is the only source of human knowledge, you have adopted a philosophical position (scientism) that cannot be verified, or falsified, by science itself. It is, in a word, unscientific.³

Likewise, we find extreme orthodoxy within religion that rejects all other avenues for seeking truth, claiming that truth can come only from revelation concerning the creation of our beautiful world and all other aspects of human life. Both worldviews put limits upon human inquiry. Neither reality is a healthy place in which to live and to learn and to progress. We must become more comfortable with uncertainty.

“To claim there is nothing knowable outside the scope of science would be similar to a successful fisherman saying that whatever he can’t catch in his nets does not exist.” —Thomas Burnett

Think about it: From a spiritual standpoint, how many of you would claim that you know everything there is to know about the gospel of Jesus Christ? I certainly wouldn’t claim that. Likewise, no self-respecting scientist who truly understands the nature of science would claim that we know all truths about the natural world. We still don’t fully understand all the causes of cancer or how to cure it. If we thought we knew everything, the scientific enterprise would come to a screeching halt.

Dogmatism—in science or in religion—closes down your ability to learn and progress. If something seems to conflict between what science reveals and what you have learned through your religious faith, don’t abandon one or the other. Hold off judgment, be patient, and keep an open mind to truth from both sides.

When he was an apostle, President Russell M. Nelson said at the dedication of the BYU Life Sciences Building, “There is no conflict between science and religion. Conflict only arises from an incomplete knowledge of either science or religion, or both.”⁴

Do not be so proud that you cannot accept that you may not know everything. Be patient and stay faithful, and in time, understanding will come. And please keep in mind that your eternal salvation does not depend on your complete understanding of science. If learning scientific theories puts your faith in jeopardy, choose your faith. Choose your faith until you can better understand the science—or until science can provide better explanations. I firmly believe that both truths—religious and scientific—exist in harmony.

Bringing Faith and Science Together

Now that we better understand these two epistemologies, let me share an example of how using both ways of knowing has profoundly blessed my life in the midst of deep trial and sorrow.

After I had been married for a few years and just before I finished my master’s degree at BYU, the Lord blessed us with a child. Everything seemed normal with the pregnancy, until I delivered. Thankfully my son was just fine, but I nearly bled to death during the birth and then again six weeks later. It turns out I have a condition called Asherman’s syndrome, which causes excessive growth of scar tissue in my womb. As a consequence, when I get pregnant, the baby’s placenta grows lobes in and around scar tissue, resembling more of an octopus than the nice round organ that it is supposed to be. It also makes delivering the placenta extremely difficult. However, we did not learn this at the time, and after an emergency procedure, I thought all was well.

“I always thought the Atonement was just for sinners. But it goes so much deeper than that.” —Jamie Jensen

Upon becoming pregnant with our second child during my PhD program at Arizona State University, signs began to indicate that all was not well. After a frantic drive to the emergency room in the middle of the night because I had awoken in a pool of blood, we found out that our precious baby had implanted right at the opening of the cervix—a condition called placenta previa—having nowhere else to go due to scar tissue. After six more months of hospital visits, scares of losing the baby, and being driven around in a disabilities cart to all my classes at ASU, I delivered a second healthy baby boy. And, once again, I nearly bled to death, this time quite significantly, to the point of having some serious complications and needing blood transfusions. It was then that I discovered my problem and was told that I would likely not be able to have any more children.

Now I had two beautiful boys, and I certainly felt blessed beyond measure, but I had always had it in my mind that I would have a bigger family, and this news was devastating.

At this point I had two problems to fix—two puzzles to solve—and I needed two solutions:

• My soul had been injured. I longed for more children, and my heart ached. How would I heal my soul?

• My body was broken. How would I heal my body?

I know that the Lord can do all things. He could remove my trials and grant me a miraculous healing, without me lifting a finger. But I can tell you with fervent belief that my trials have a purpose; they have made me stronger and more empathetic. I am grateful for my trials. As the Lord explained to Joseph Smith:

If fierce winds become thine enemy; if the heavens gather blackness, and all the elements combine to hedge up the way; and . . . if the very jaws of hell shall gape open the mouth wide after thee, know thou, my son, that all these things shall give thee experience, and shall be for thy good. [D&C 122:7]

So I needed this trial, and the Lord had a plan. I could have just sat back and prayed, putting all responsibility on God, and waited for Him to bestow a miracle upon me. Instead I went and searched diligently “out of the best books” (D&C 109:7), learned all that I could learn, and sought the guidance of the medical community in helping me navigate these uncharted waters—all with a prayer continually in my heart that God would help me bring my own miracle to pass.

After finding a world-renowned surgeon who specializes in Asherman’s syndrome, my husband and I headed to California for several surgeries, long agonizing nights in hotels with me sick from pain medications, and complicated recoveries.

But a year later I brought my son Gage into the world, and after another round of surgeries, I brought my fourth son, Emmitt, into the world four years later. I have been greatly blessed. So many women with this condition never have children at all, and I feel deep sorrow and sympathy for their plight. For whatever reason, the Lord saw fit to bless me with a miracle. But that miracle came about through the angels who work in medicine and the healing of my soul through much prayer and supplication. I am grateful that I can have both at work in my life.

Act—Do Not Just Be Acted Upon

Speaking of agency to a group of African Saints, Elder David A. Bednar (BA ’76, MA ’77) stated, “You and I . . . are agents. We have the power in us to act, not simply to be acted upon.”⁵ The Lord has given us agency, and with that, He expects us to act using all the knowledge and understanding we have gained here on Earth. I firmly believe that God wants us to act upon our scientific understanding and bring about God’s blessings of healing and a better life. God has given us the gift of intellect, and He expects us to use the laws of nature to better our lives.

When my son was just 6 years old, he suffered a physical attack that caused his fragile young mind to break, as it were. Prayers and fasting, pleading with the Lord, and years of medical attention and amazing medications have brought him back from a seemingly hopeless place to a happy and healthy life. It was not just prayers that helped him, although those certainly helped. It was a use of the knowledge the medical community has gained that ultimately brought about God’s miraculous gift of healing. We acted instead of just being acted upon.

Through this experience, I learned something about the Atonement that I hadn’t understood before, even after growing up in the Church. I always thought the Atonement was just for sinners. But it goes so much deeper than that. When Christ was suffering in the Garden of Gethsemane, he felt all the pains and sufferings of us all.

Elder Neil L. Andersen (BA ’75) said:

Our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, through the incalculable gift of His Atonement, not only saves us from death and offers us, through repentance, forgiveness for our sins, but He also stands ready to save us from the sorrows and pains of our wounded souls.⁶

The pain that Christ felt was so great that he bled from every pore. It wasn’t just godly sorrow for wrongdoing—it was the pain of a mother longing for children, the pain of a parent whose child had been harmed, and the pain of a child who suffers trauma. It was all the pain we would ever suffer. And thus the Atonement is for that, too. It can help my suffering heart to heal, it can give me the strength to forgive those who have harmed me or my family, and it can comfort my children through their pains and sorrows. It can comfort you through yours. It is for all of that—not just for sin.

The deep and profound spiritual understanding of truth has aided in our family’s healing process in a way that scientific understanding never could. Likewise, the scientific understanding that helps us deal with the physical realities of Asherman’s or my son’s trials have equally impacted our healing process. Without these beautiful truths discovered through science, our lives would be crippled and we would not have become who we are today. It is these two ways of seeking truth—brought together in harmony—that have healed and continue to heal my soul.

Jamie Jensen, a BYU associate professor of biology, delivered this devotional address on Nov. 3, 2020. Find thefull text, audio, and video at speeches.byu.edu.

Feedback: Send comments on this story to magazine@byu.edu.

NOTES

- Pierre C. Hohenberg, “What Is Science?” unpublished, December 2010, p. 1.

- Lexico.com, s.v. “dogmatism.”

- Thomas Burnett, “What Is Scientism?” Dialogue on Science, Ethics, and Religion, Programs, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Oct. 30, 2018.

- Russell M. Nelson, quoted in Marianne Holman Prescott, “Church Leaders Gather at BYU’s Life Sciences Building for Dedication,” Church News, April 17, 2015.

- David A. Bednar, quoted in Kevin S. Hamilton, “Act . . . Not . . . Acted Upon,” Africa Southeast Local Pages, Liahona, March 2018; referring to 2 Ne. 2:14–29.

- Neil L. Andersen, “Wounded,” Ensign, November 2018.