Everyday people dig deep to give generously to BYU.

Ever since she was a little girl, Tiffany L. Sabin, ’04, has wondered how things work in the natural world—like why leaves change color in the fall and how a scraped knee heals into a scab.

She decided then that she wanted to be a scientist, and she’s now well on her way. In April she completed a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry at BYU, and in September she began work on a PhD at Duke University. She gives a good part of the credit for her graduate admission to laboratory research she did as an undergraduate with a fellowship funded by former BYU faculty members Eileen and Victor Bunderson.

“My undergraduate research was far more important than my grades for my admission to this program,” says Sabin. “That experience got me into my dream school.”

Despite its immense value to her education, Sabin still had not heard the story behind the $1,500 fellowship when she donned a black robe and walked across the wood floor of the Wilkinson Student Center Ballroom to receive a diploma.

So it goes with many such contributions: While donations from large corporations and wealthy individuals make headlines, the widow’s mite often goes unnoticed. Yet those donations—large and small, given with great sacrifice by ordinary people—amount to extraordinary gifts that have lasting impact on student lives.

Behind these lesser-known donations also lie tales built around dreams, passions, and consecration. Hundreds of such stories could be told, each moving and inspiring in its own way; three are shared here.

A Still-Used Camera

In 1985 professional photographer Esther Abbott took her last photo. She was 73, and she figured she’d had a good run of nearly 50 years, with thousands of photos appearing in magazines such asLife, the Saturday Evening Post, Arizona Highways, and Collier’s. But now, with terrible irony, she learned she had macular degeneration, a progressive dimming of vision in the center of the retina. She could no longer focus on the ground glass of her beloved Deardorff, a camera that produces negatives large enough to yield photos with the fine detail that magazines like Life demand.

The Deardorff sat in a closet for years. As digital cameras swept the photography market, Abbott wondered if the aging camera would ever be used again. Today’s photographers, she thought, might consider the Deardorff something of a relic, with its wooden body, bellows, and black focusing cloth. Who would want her Deardorff now?

She doesn’t remember the exact day it occurred to her that someone at BYU might make use of her equipment, which included a second Deardorff and valuable accessories, but she remembers the factors that aligned to spark the idea even though she was not a BYU graduate or a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. First, her partner for many years in a photography business was Halvan L. Jones, a member of the Church who always impressed her as a person of integrity. Second, she taught a portrait photography course at BYU one summer more than 40 years ago. Third, she and her late husband, Chuck, also a professional photographer, enjoyed photographing Church historical sites in the 1960s, including Joseph Smith’s birthplace, Nauvoo, and Carthage. And fourth, she was born on the 24th of July.

“All my life I wished I’d been born on July 4, the big holiday,” says Abbott, now 93. “But then I came to find out how important the 24th is to Mormons. That told me who to give my cameras to.”

She contacted BYU, which agreed to accept the gift-in-kind. Soon three large boxes showed up in the Brimhall Building. John Telford, a fine-art photographer and chair of BYU’s Visual Arts Department, opened them up and saw the two Deardorffs, five lenses, and a pneumatic tripod.

Esther Abbott, a professional photographer for nearly 50 years, donated two classic Deardorff cameras and other photographic equipment to BYU’s Visual Arts Department after losing much of her vision to macular degeneration. Photo by Suzette Millar Anderson, ’04.

“I was amazed,” says Telford. “The best of the digital cameras cannot approach the quality of these.”

He has a Deardorff himself, and he considers Abbott’s cameras a rare gift. He soon wrote a letter to thank her and told her his students were already using the cameras. Next thing he knew, another box arrived. Inside was a large stack of 5×7 transparencies of many of Abbott’s best photos. On top was a note, handwritten in very large letters made with a fat black marker.

“It was just so poignant to me,” says Telford. “When I first opened the box, it was reeking from the smell of those markers.”

In her note, Abbott wrote that she “was delighted to know that favorite camera of mine was in using hands. . . . Better [the equipment] should end up with you than my closet shelf. Again, you shouldn’t thank me for anything—you have made me happy to know that the equipment that stood me in good stead for 50 years is still functioning.”

Students today use Abbott’s cameras in a class called Alternative Photography Practices, where they “use historic and very esoteric processes that are very fine-art oriented,” says Telford. He believes it’s valuable for his students to learn about, and even keep alive, a form of photography that is winding down.

“These cameras were the mainstay of professional photography for the better part of the last century. The larger the camera, the more detail. This is fine-art photography, not commercial photography or portraits. It’s art for art’s sake, aesthetic and expressive.”

Abbott lives in Santa Cruz, Calif., her home of 40 years, where she plays the piano at nursing homes and the organ for Sunday services at the Salvation Army. Born a Presbyterian, she says she became a Salvationist because they act on their religion. She admires Latter-day Saints for the same reason and was pleased when BYU was able to accept her in-kind donation.

“While some people talk about things, the Salvationists do things. That’s also the main attribute of Mormons. They act. They live their religion.”

Though she can no longer read music, she practices the piano and organ “like crazy,” she says, because she has to memorize every piece.

“But photos,” she says without a hint of melancholy, “no more!”

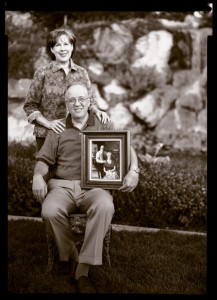

Victor and Joyce Bunderson enjoy their yard, designed by Victor’s first wife, the late Eileen Bunderson, pictured in the photograph Victor is holding. Eileen, a botanist, and Victor saved for years to endow a fellowship to support women pursuing studies in science. Photo by Katie A. Smith, ’04.

Saving For Science

Alissa Bunderson Hartley, ’98, was five years old when she started going to BYU classes in the late 1970s with her mother, Eileen D. Bunderson, PhD ’83. She’d play on the lab floor as her mom worked and follow her around parks and woods while Eileen took notes for her dissertation on juniper tree diseases.

“It was a great childhood,” says Alissa. “I pretty much lived in the Widtsoe Building with her. I can still diagnose diseases in juniper trees.”

By the early 1990s, Eileen and her husband, Victor, were sharing a joint faculty appointment in BYU’s Instructional Science Department (now Instructional Psychology and Technology). Eileen had built a reputation as an outstanding teacher and a dedicated advocate for women in science. At home in Orem, Victor remembers, they started talking about giving BYU a donation large enough to send a strong message of confidence to young women heading toward science careers. Their single salary was modest, but they started earmarking a few dollars here and a few stock certificates there, hoping that eventually one of Victor’s entrepreneurial side businesses might yield the requisite funds for an endowed fellowship.

By 2002 their hope was realized, but Victor would have to enjoy the achievement without Eileen. In 1998, at the age of 61, she died from ovarian cancer. Today the Eileen Bunderson Fellowship for Mentored Student Learning honors her name and carries out her wish to support young women who otherwise might feel discouraged about making their way in traditionally male-dominated fields.

The vision for the fellowship reflects the challenges Eileen faced in her own education. “It was very difficult for my mother at that age and of her gender in the sciences—being in her late 40s,” says Bethanie Bunderson Newby, ’84, Eileen and Victor’s oldest daughter. “Mom wanted the fellowship to help counter attitudes that a woman’s education is less important than a man’s.”

Bethanie is seated in the Orem living room of her sister Alissa, along with her father and his second wife, Joyce. Though Joyce never met Eileen, she’s also a scientist and fully supported Victor in going forward with the $340,000 endowed fellowship. Twice now, says Victor, he’s been “smitten by these independent, smart women.”

The fellowship supports several students each year in faculty-mentored research, with women a priority but men also considered. Bethanie and Alissa say their mother was not militant about her views but rather was a warm, supportive woman who believed it was important to communicate what she learned from her experiences.

Bethanie says their mother taught them “that you have to work for what you get and there are going to be stumbling blocks out there.”

It’s those life lessons that the family of Eileen Bunderson hopes her fellowship can help others learn. At the same time, they hope to keep alive the name of a woman they revere.

“We wouldn’t be the people we are without her and her example and her influence,” says Bethanie. “We’re just so lucky that she was our mother.”

Scrimping, Saving, and Consecrating

It’s been almost 15 years since Latter-day Saints were asked to contribute to ward and stake budgets, building funds, and the welfare program—all in addition to tithing. Howard W. Barben remembers those days well, especially the year he was made bishop of a ward in the area of Salt Lake Valley that is now West Jordan. It was 1954, and few of Barben’s ward members could meet their “assessments” without a mighty struggle.

So Bishop Barben decided to be innovative. With ward funds, he bought a 156-acre farm at $120 per acre and asked his ward members to contribute labor instead of cash to meet their budget assessments. At the same time, he bought 25 acres for himself and his family, then leased the land out to a farmer.

The ward plan worked well for a year, but then the Church welfare committee interceded. They thought the farm was too much work for one ward, and they persuaded Bishop Barben to turn the farm over to the stake, which he did. Soon he was made stake president and ended up with responsibility for the welfare farm for 15 years.

Nearly 50 years after the farm was purchased, the land sold for $9 million. Barben is thrilled his inventive solution to a vexing problem eventually resulted in a tidy sum for the Church.

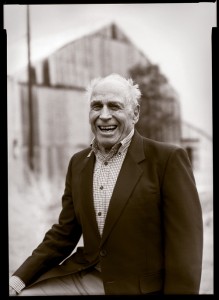

Howard Barben purchased and managed this former Church farm decades ago as a bishop and stake president. the $9 million the Church received when it sold the land is just a portion of the financial legacy the 92-year-old Barben continues to leave to the Church and its schools. Photo by Becky Spotten Grover, ’04.

The welfare farm adventure was one of Barben’s earliest efforts at consecrating his all to building the kingdom, including his creative approach to money. He seemed to have access to bonus money often over the years, and he developed a talent for using it to the maximum—always for the benefit of the Church or its higher-education system, especially BYU.

A prime example was taking advantage of matching funds offered by his employer. He spent most of his working years as the manager of AMOCO’s building at 3rd South and Main in Salt Lake City. The company matched employees’ charitable donations up to $1,000 per year at first, then began double matching up to $500 and single matching up to $10,000 a year. Barben and his late wife, Laverne, made the maximum contribution for more than 20 years. The last 15 years, their donations totaled about $22,000 annually to BYU, BYU–Hawaii, Ricks College, and LDS Business College. As a self-described “average” breadwinner and father of seven daughters, the contributions did not come easily.

“We kind of scrimped and saved, but somehow or the other the Lord blessed us so that we could make these payments,” says Barben. “I really felt the more I gave, the better position the Lord put me in to give.”

In the late 1990s, he decided to sell the 25 acres he’d bought for his family when he purchased the acreage for his ward. It sold for an astounding $4 million. He hadn’t earned the money, he felt, so he was obligated to give it to the Lord. With his fiscal savvy, he contributed the money to the Church in the form of a trust with the agreement that from the interest, each daughter would receive about $20,000 per year and he would receive about $100,000 per year. They all save on taxes, and he turns around and donates his yearly dividend to the Church.

“I would no more dare take money that I thought the Lord had blessed me with and that I hadn’t out and out earned than I would have my head chopped off,” says Barben, now 92, seated on the back patio of his daughter’s home in West Jordan, not far from the former stake farm.

He’s even earmarked life insurance policies totaling $1.9 million for the Church and its educational system. Some will go to his children first, with the agreement they will donate the entire amount. They save on their taxes, and the Church and its schools benefit.

Barben figures that by the time he dies and his life insurance policies have paid out, he will have contributed nearly $16 million to the Church and its colleges or universities. He unabashedly discloses these figures, emphasizing that the money isn’t his anyway. And it’s all from “a common, ordinary” man who never went to college.

Heber J. Lloyd has known Barben for decades, both personally and in his position as a development officer at BYU. He says Barben always makes his donations unrestricted, meaning they can be used anywhere the money is needed. That makes the impact of the donations difficult to pinpoint, which doesn’t bother Barben at all.

“He’s taught a whole generation and the generation after that how to give generously without expecting congratulations in return—and without a bundle of money,” says Lloyd.

For Barben, the dividend is not only a feeling of satisfaction in giving, but also some fun in his later years as he gets to know “tremendous people” while attending BYU banquets, alumni meetings, and football games.

“But,” says daughter Carol Barben Taylor, ’68, “the most fun for him has really been giving the money back to the Church. It’s the most fun way to spend the money.”

Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

The Widow’s Mite

By Sarah E. Jenkins, ’05

From a thick white binder, Linda M. Palmer, ’71, director of annual giving for BYU, takes out a single note written in careful but shaky cursive.

“Dear Linda Palmer,” it reads, “Thank you for including me in your BYU gift giving. I am 84 years old and on a limited income. However, I did receive a Christmas gift, and so I can then share with you in this important project.” The note, written by Vera A. Rice, was accompanied by a $100 check, her Christmas gift. The postscript to her letter simply says, “I decided to send the entire check.”

In Palmer’s office are hundreds of these letters, each expressing the donor’s desire to help the students at BYU. “It really is the widow’s mite,” says Palmer. “They believe in the students, they believe in what we’re doing, and it’s their way of expressing support for us.”

Palmer hopes that the spirit of giving embodied by these donations will be passed on to others. “Those of us who are just ordinary people, who don’t have a lot of assets, rarely feel that we can ever be philanthropists, that we can be in the realm of the Carnegies or the Rockefellers or the Huntsmans, those people who are so noble in their generosity. But I really think that we can,” says Palmer. “When we just do what we can, it adds up.” From students to alumni to friends of the university, BYU is constantly being added to by ordinary people sacrificing to give extraordinary gifts, including those mentioned in the following stories.

Retired mail clerk Samuel E. Claridge Jr. has decorated his California apartment with two things: Mickey Mouse and photographs he has been sent of students he has helped in more than a decade of donating. “Sam really does believe that he’s helping to save a life, and in a way, these are his children,” says Gregory R. Nolte, ’74, a BYU donor liaison. “Through the years, Sam has not only given generously on a yearly basis, but he has also given enough to establish an endowed scholarship at BYU–Idaho in memory of his deceased wife, Mary.” The beneficiaries of Claridge’s annual gifts include students at all of the BYU schools as well as at the Church College of New Zealand.

When a team of five BYU MBA students won the 2003 Thunderbird Innovation Challenge they were named “The Most Innovative MBA Team in the World.” It didn’t take long before they were also the most generous MBA team in the world, giving $2,000 of their $20,000 grand prize to the Marriott School. “We were really impressed with how willing the Marriott School was in supporting us in this competition and in our educations, and we wanted to help provide similar opportunities for future students,” says Aaron J. Hopkinson, ’02. Hopkinson’s teammates were Colin A. Jones, ’04, David L. Roach ’99, Scott C. Porter, ’97, and Geoffrey M. Howard, ’00.

Chad J. Flake, ’53, worked in the Harold B. Lee Library’s Special Collections, lived in a modest apartment, drove an old car, and had over a million dollars in his bank account. “When he passed away,” explains Flake’s friend and university librarian Randy J. Olsen, ’73, “he left the library his entire estate, which is the second largest donation to the library. He lived by humble means and literally put his life savings away for the library after he moved on. The library was his family and he was beloved by the staff. He dedicated his life to this library and to supporting students.”

Sharing a home in Orem, Utah, Ramona Morris and Beverley Nalder, ’52, also share the belief that women need an education. For over a decade Morris, a retired Provo High School counselor, and Nalder, a retired BYU counselor, have funded a four-year scholarship to BYU, awarded to the top female Provo High School student each year. Nalder also funds a second scholarship for women returning to complete their BYU education and occasionally a third scholarship in memory of her sister, Nadine Nalder, ’53. “I don’t view it as a sacrifice,” said Nalder. “I probably could have had a new car, or I could have gone on a big trip, but I’m not hurting because I’m going without those things. It’s just a matter of seeing this as more important.”