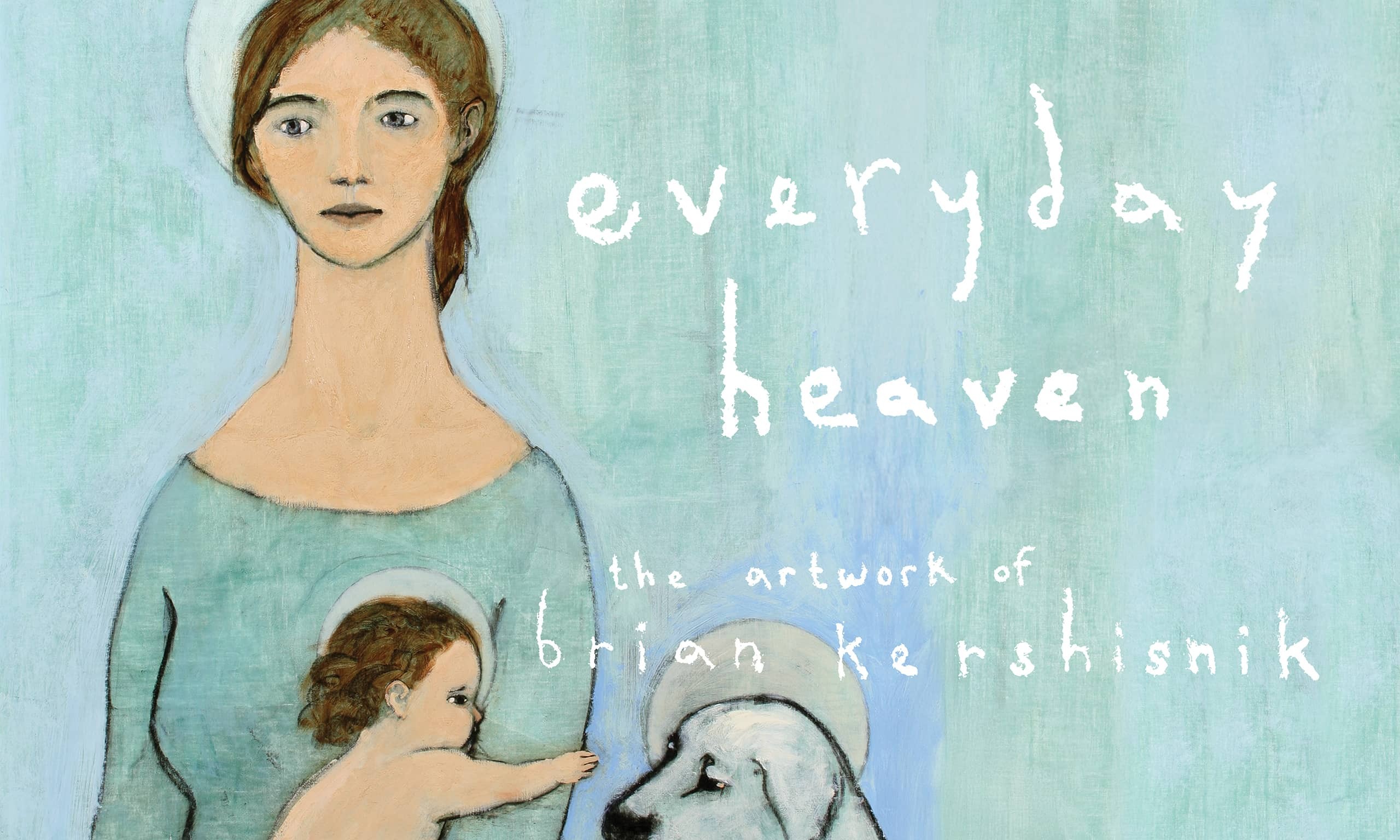

Everyday Heaven: The Artwork of Brian Kershisnik

Featured in a current BYU Museum of Art exhibit, Brian Kershisnik’s work brings heaven to earth and elevates the mundane with meaning.

By Michael R. Walker (BA ’90) in the Winter 2025 Issue

Look carefully at a painting by Brian T. Kershisnik (BFA ’88), and you might just find yourself.

The beloved contemporary artist is known for painting universal themes and everyday scenes—of women, men, children, babies, pets—sometimes with angels reaching down or looking on with interest.

One of his most famous angel-graced works is Nativity, a mammoth mural acquired by the BYU Museum of Art (MOA) in 2011. Across the 17-foot-wide canvas, a parade of angels—joyful, weeping, astonished—stream past Joseph, Mary, and baby Jesus, along with a handful of midwives, a dog and its pups. “I don’t call it The Nativity,” Kershisnik says. “The name is Nativity because it is yours too. The miracle of Jesus’s birth—it was messy and painful and difficult, like yours was.”

At a 2021 MOA gallery Q&A, 6-year-old Wade asked the artist about that crowd of angels. “It’s everybody. . . . If I’ve done my job right, Wade, it is you,” Kershisnik explained, adding to the audience, “and all of you.”

The Difficult Part, a MOA exhibition running through May 3, 2025, is a retrospective of Kershisnik’s works, the culmination of a years-long effort cocurated by former museum director Mark A. Magleby (BA ’89) and current director Janalee Emmer (BS ’97, MA ’01).

The show invites visitors to find themselves in the scenes and characters depicted—be they heavy-footed dancers, emotional angels, resilient mothers, or heaven-aware dogs. As they pass by Kershisnik’s works, viewers may ask themselves: “Am I an angel? A struggling Saint? Or perhaps I’m an angry baby?”

Holy Humor

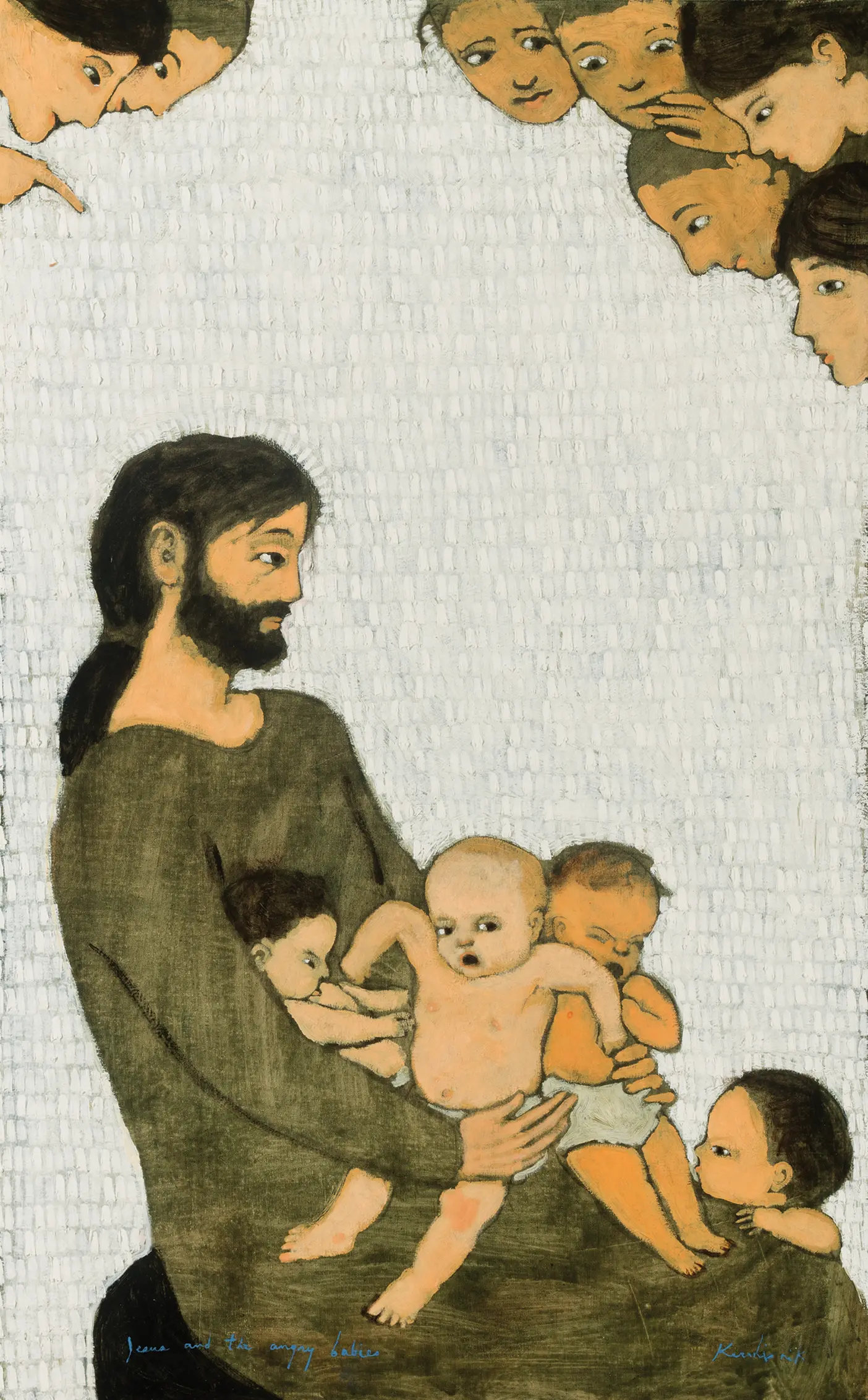

Angry babies?

The idea started as a visual joke that Kershisnik sketched out for an artist friend. “I was just making him laugh, because in all of the pictures of Jesus with children, they are incredibly, beautifully well behaved and glad to be there.” But these babies, as later developed in Kershisnik’s work Jesus and the Angry Babies, are none too happy about sitting on a stranger’s lap. “This was . . . the mom’s idea, and the kid doesn’t know who this Man is.”

Although at first he was just being playful, Kershisnik says that after creating the “angry babies” sketch, the idea took on deeper meaning for him. He came to see it as a profound visual metaphor that shares the reality of misbehaving humans trying to reconcile a relationship with perfect—and patient—heavenly beings.

That melding of humor and spiritual depth is to be expected from Kershisnik, says Emmer. “Brian has a wonderful sense of humor, and you can see that humor in his art,” she says. “He has a deep sense of his spirituality, and his relationship with the divine is really important to him. You see both the humor and the holiness in a lot of who he is.”

Even though much of his work is not overtly religious, Kershisnik says his beliefs shine through. “I’m a religious man, and there is religion in all of my work,” he says. “It’s impossible for me to ignore my view of the world or the cosmos or the significance of our relationship with God.”

Kershisnik also draws inspiration from his childhood. The youngest in a family of four boys, he was born in Oklahoma City. His father, David, was a petroleum geologist, taking the family all over the world. They lived in Angola, Thailand, Texas, and Pakistan, giving Brian a broad view of a variety of peoples and ideas.

As part of his artistic journey, Kershisnik first dabbled in architecture at the University of Utah. But after his mission to Denmark, he tried his hand at ceramics at BYU. After his first year, Kershisnik started the summer in the pottery studio with Joseph W. Bennion (BFA ’82, MFA ’86).

After some time handling clay, Kershisnik learned he was “not really a potter.” Joe’s wife, Lee Udall Bennion (BFA ’86), suggested he try creating something with her paint box and a canvas instead.

He first painted a self-portrait, then a couple of landscapes. After completing a batch of work, he realized his calling to drawing and painting: “I think there’s something here that I need to do.”

It wasn’t long before gallerist and BYU art history teacher Dolores Ritchie Chase (BA ’58) noticed his work and helped launch his professional career.

And so Kershisnik followed in his father’s footsteps and became an “oil explorer” (with the notable difference of using linseed oil instead of fossil fuel).

Those explorations examine suffering and serving, weeping and wrestling, flailing and flying. His subjects are rarely alone but act in pairs or in a community of Saints, where men and women make significant mortal choices. “In a million ways, incidental and huge,” he says, “every day we’re choosing between life and despair.”

Harvesting from Chaos

Kershisnik is nothing if not prolific. He has painted more than 4,000 works—and recently added sculptures to his repertoire. In his studios in Provo and Kanosh, Utah, he works on dozens of paintings at a time.

“It’s kind of a hack or a strategy that takes the pressure off any individual piece,” he says. “I’m working on so many that if I don’t know what to do or where it’s going, I just work on something else.”

He starts with rough ideas from his sketchbook, mixes up his paints, and goes exploring. He calls the process “harvesting from chaos.” And each painting is just a part of an ongoing process: “For an artist, a painting is like a sentence in a novel that you’re writing your whole life,” he says.

Kershisnik’s skills extend beyond two-dimensions—and the good ideas he pulls from the chaos are often expressed in multiple ways. He’s an accomplished cook, a woodworker, and a songwriter, guitarist, and lead singer in a band called Tiny Bicycle Parade. He’s a Sunday School teacher, a husband, and a father of three adult children.

But painting fills most of his time and remains Kershisnik’s consuming passion.

MOA director Emmer is in awe at his productivity. “Art is so much of who Brian Kershisnik is—he exists for it,” she says. “It very much defines him, that continual kind of creativity. I think it gives him meaning in his life. That’s almost exhausting to watch. He is relentless.”

His prodigious output often defies simple explanation. And that’s by design.

When asked what a particular painting means, Kershisnik often says, “I don’t know,” or otherwise answers imprecisely.

“If I am not careful about how much I reveal my own intentions, I run the danger of closing the door on what the painting can mean to you or anyone else,” he writes on his website. He contends that what a viewer takes away is “every bit as legitimate as what I intended, possibly more legitimate than what I intended.”

While he is willing to “talk about the experience of painting or discuss ideas of possible meanings,” he concludes that “art should open up, not close down conversation.” It’s a conversation colored by the viewer’s own experiences and perspectives. And he says that when he completes a work, he changes roles, moving from artist to spectator, joining those who view the work and try to find inspiration and meaning.

“One of the things I love most about Kershisnik’s art is the way it invites me to consider things from different perspectives,” says Liz Donakey, the MOA’s educator for the exhibition. “Whether it’s a story I’ve known since I was little, a more general idea, or anything else, Kershisnik’s work encourages me to ask questions and contemplate viewpoints I may have overlooked. His paintings, sculptures, and prints allow me to bring my own interpretations to them.”

Intricate Dances

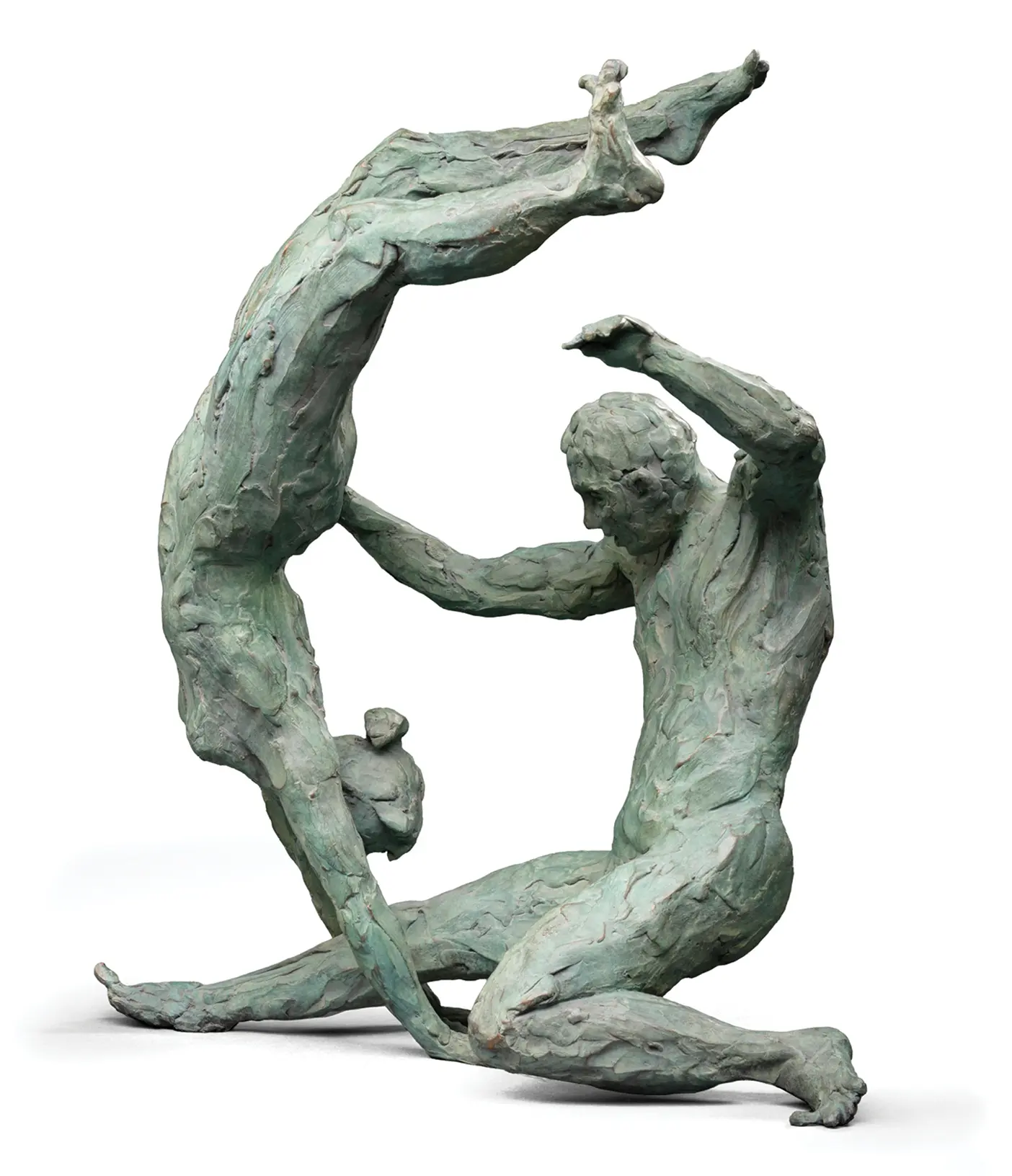

In studying Kershisnik’s work for the exhibit and an accompanying catalog, Emmer found that, again and again, the images are founded in relationships. The exhibit opens with and is named after Kershisnik’s The Difficult Part, a bronze statue of a couple in an awkward dance.

“A man and a woman, interdependent, are in an acrobatic posture where they’re reliant on each other and have to be aware of each other in complex and intricate ways, but each moving separately and doing something different. [He was] inspired by the marriage relationship—what are the things that are required to make this work? That it’s this incredible kind of balance between the two.”

Emmer says the idea “expands to all of our relationships . . . and even our relationship with the divine. It is this kind of balance of trust and of faith and of agency.”

Relationships are core to his painting Empathy, which was originally intended to be a diptych, two paintings depicting the two great commandments: to love God and to love neighbor. But as Kershisnik explored, he found it impossible to separate the two. In the end the paintings—and the commandments—merged and became one. “You can’t hear ‘love God with all our heart’ without it involving how we treat each other and even ourselves,” he says.

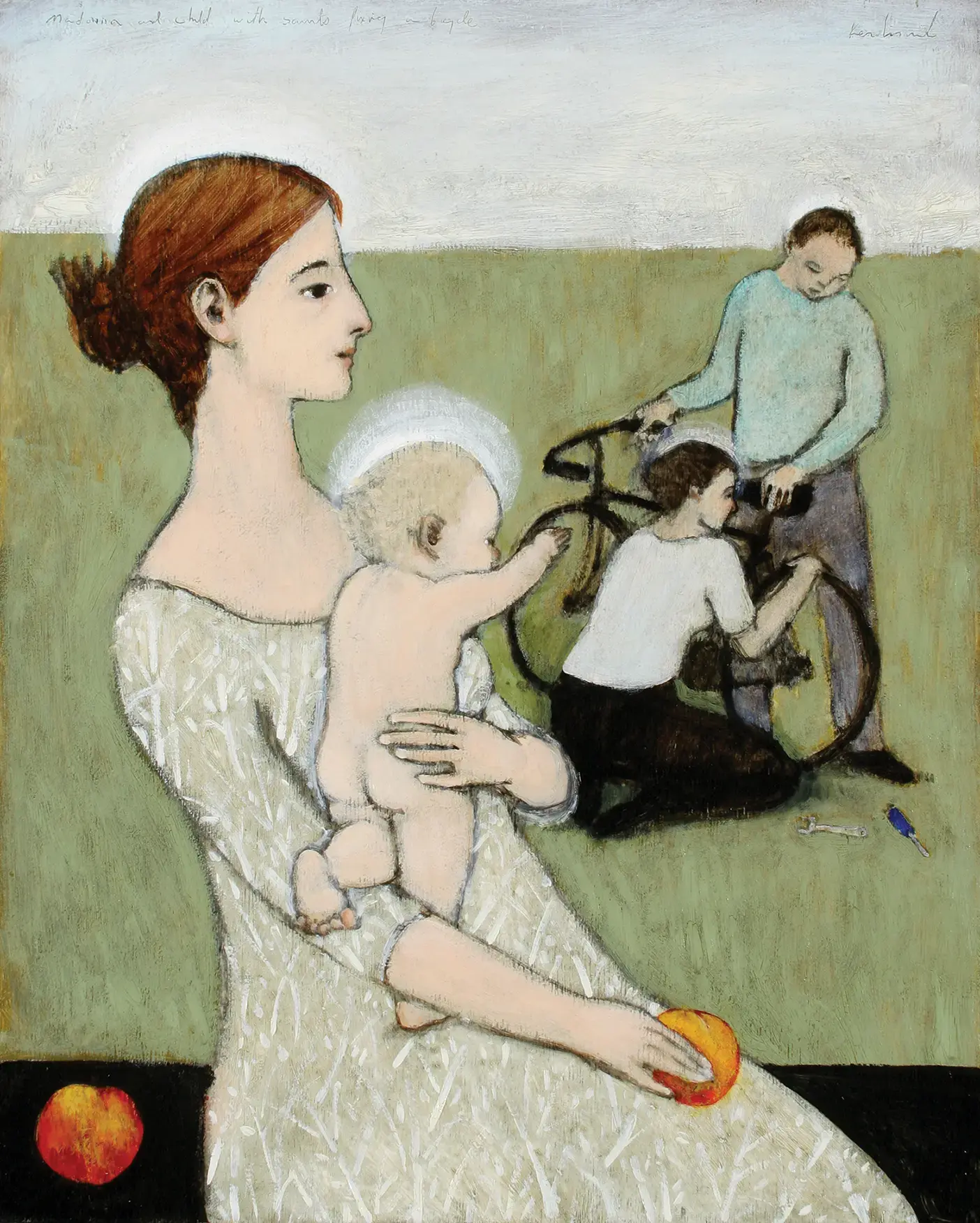

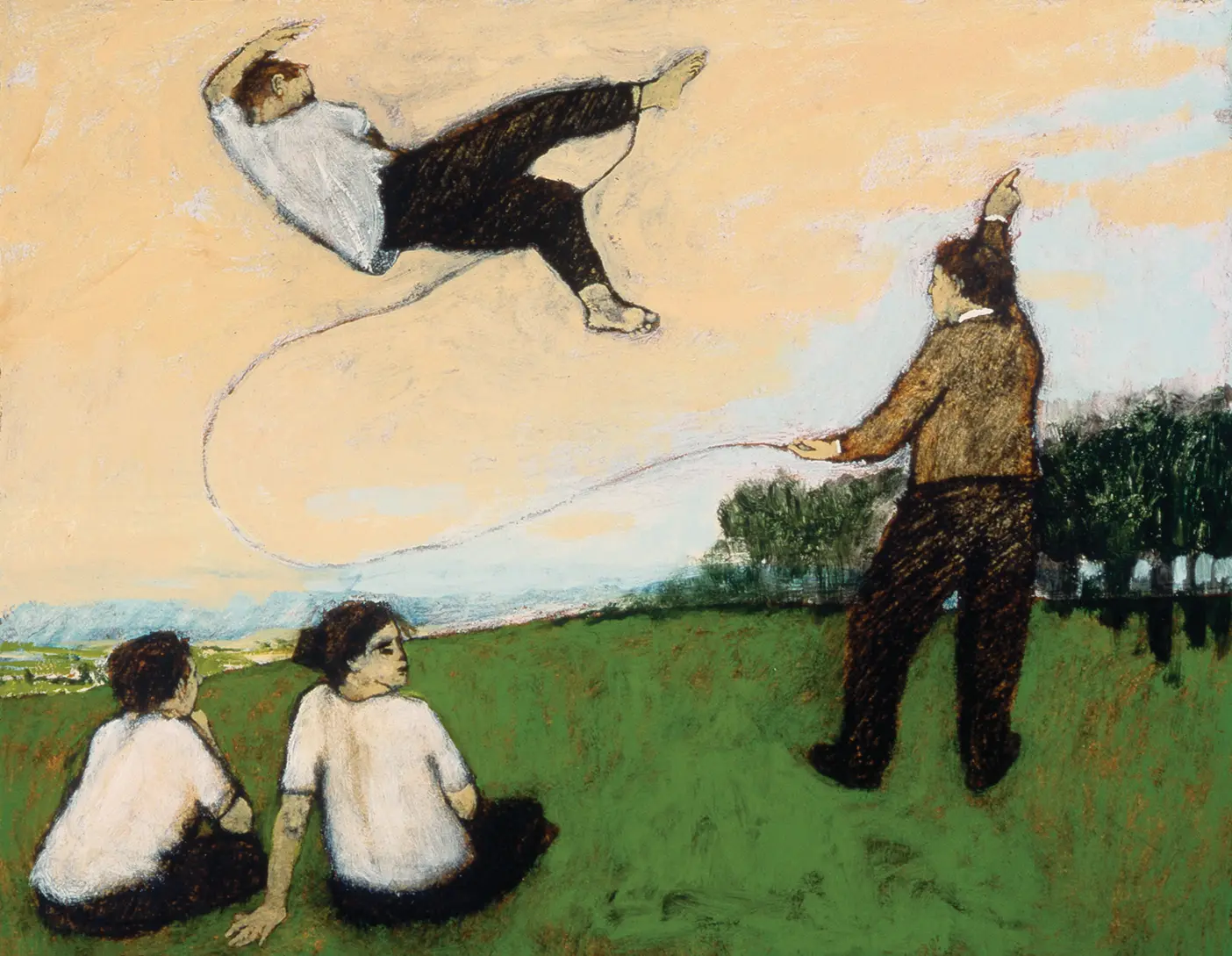

Relationships and service are key to the scenes in Kershisnik’s work—from delivering broth to helping someone learn to fly to fixing a kid’s bike.

“I did a mother-and-child painting, and it needed more in it compositionally,” he says. With a nod to Renaissance paintings, he thought, “‘Well, okay, I’ll put some Saints in.’ But my notion of a Saint is not just somebody there adoring but someone doing something.” So he painted in someone fixing a bike. “When I was little, well, that was just massively helpful in my tiny world, you know?”

Often the striving, serving Saints are female figures, what the exhibit calls holy women.

“He depicts women as very capable and thoughtful and going about engaged in great work,” Emmer points out. “He paints women in real situations, and there’s not a sense of putting them on a pedestal where they’re not given anything to do, but rather embracing women in lots of different capacities—mothers raising children, or a scholar reading a book, or women walking along the beach or gardening in the rain.”

“I did a series of tiny paintings, four in a row that were mother and child,” says Kershisnik. After adding the title Mother and Child to each, he realized there was no child in the last one. “I was going to rub it out, and I thought, ‘No, I’m going to leave it, just because I know mothers that don’t have any children.’”

At the end of the exhibition is a book for visitors to share their thoughts.

“I recently became a new first-time mom and life has been a bit overwhelming,” penned Laila N. “Even now as I write, I hold my daughter in my arms because she was crying. But coming here with her and seeing the paintings of strong women, exhausted women, mourning women makes me think that someone out there does know how it feels. . . . I was reminded today that I hold a whole world in my arms.”

Death and Hope

Amid his humor and whimsy, Kershisnik isn’t afraid to engage with tough themes, says Emmer: “the difficult part of mortality, the idea that all of us face death and loss and heartache, things that almost seem too much to bear.”

Emmer adds, “Even though there are shades of death and woundedness all around us, Brian always paints a kind of heaven that is close, that is near, that wants to intervene or help or point you in a direction. [It] doesn’t become too weighty because of the hope that is also there and the angels that want to intervene and assist and aid and comfort.”

Grad student and MOA curatorial fellow Caroline E. Johnson (BA ’23) loves how Kershisnik brings “really big and heavy, kind of scary themes down to a way that makes them really approachable and personal. He also makes things that seem so mundane, so heavenly,” she says. “He just elevates things that people would never think about, and he makes things that seem way too big to manage, much more manageable.”

In his studio Kershisnik is exploring a painting with the working title Hope. “Hope,” he notes, “contains or embraces an exquisite absence.”

When someone close to us dies, he says, “that’s kind of where hope meets the road. Our obligation as disciples to have hope means that we will live our lives in the presence of exquisite absences. We will live in a world that is not how it needs to be. We will love deeply people who are not doing what we feel they need to do. People will die, and we need them.”

He says that “maybe 95 percent of our connection to God is the yearning for something that isn’t yet. But rather than feeling like yearning is only useful until it’s fulfilled, just include that in your discipleship.” He concludes that “part of being human is figuring out how to include this difficulty in the good part. The difficult part is also the good part.”

Human Moments

On an afternoon visit to the MOA exhibit, a couple browses through the pieces in what feels like a scene from a Kershisnik painting played out in real life.

“I would like a print of that one,” says the woman, seated in a motorized wheelchair. “Which one is that?” asks her husband.

“Flight Instruction with Practice.”

They both pause, pondering the possible meanings of the clumsily floating figure tethered like a kite, the string held by a friend.

Then as they peer into the next gallery, the man asks, “Wanna keep going?”

“Yeah.”

“You’re not tired of walking?” he quips.

They both chuckle and continue on.

Johnson loves how the artwork “is just so human and so real.” She adds that Kershisnik “grapples with every single topic in a way where everything feels funny and manageable, but still respectful and reverent.”

Which explains one of her favorite pieces, Mother and Child with Dogs Vomiting. “It is just part of everyday life that has never shown up in a painting before, and everyone who has a dog has to live through that. It’s just so funny,” says Johnson, adding that Kershisnik is “not afraid to show what everyday life is like.”

Nor is he afraid to present un-finished ideas, still developing, still exploring.

With unique access to the artist, Johnson was able to hear Kershisnik discuss his process, especially how his paintings reflect his ongoing faith journey. She notes that in the exhibition, next to Nativity, finished in 2006, is Unfinished Nativity Study, still not finished in 2024.

“I think that’s just a good example of the fact that this final product isn’t his final product. It’s a faithful, ongoing process of constant learning, reevaluating, and moving closer to the Savior,” she says. “Being able to see art more as a faith process than a final destination has been a really special experience.”

Feedback Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.