When political disagreements arise, an alumna advocates for kindness and curiosity.

Marianne Holt Viray (BA ’96) first experienced political tension while participating in Model United Nations as a teenager living in Lisbon, Portugal. Representing a country with other delegates, her team debated and developed policy positions to best advocate for the country’s interests. She quickly learned “there are many perspectives from which to approach any policy discussion,” she says. “That experience kind of lit me up inside.”

As a BYU political science major, Viray became fascinated with the civil rights movement, freedom of speech, and “how different sides accessed and utilized that freedom to advocate for their position.”

After graduation Viray worked in Washington, D.C., for the Center for Public Integrity and cofounded the nonprofit Campaign Legal Center. In D.C. when she watched the McCain-Feingold Act challenged in the courts and escalated to the Supreme Court, she realized “there’s always going to be disagreement around policy.” However, “disagreement and conflict aren’t bad words,” says Viray. “[It just] means we’re two individuals with different perspectives and backgrounds. We just have to do it better.”

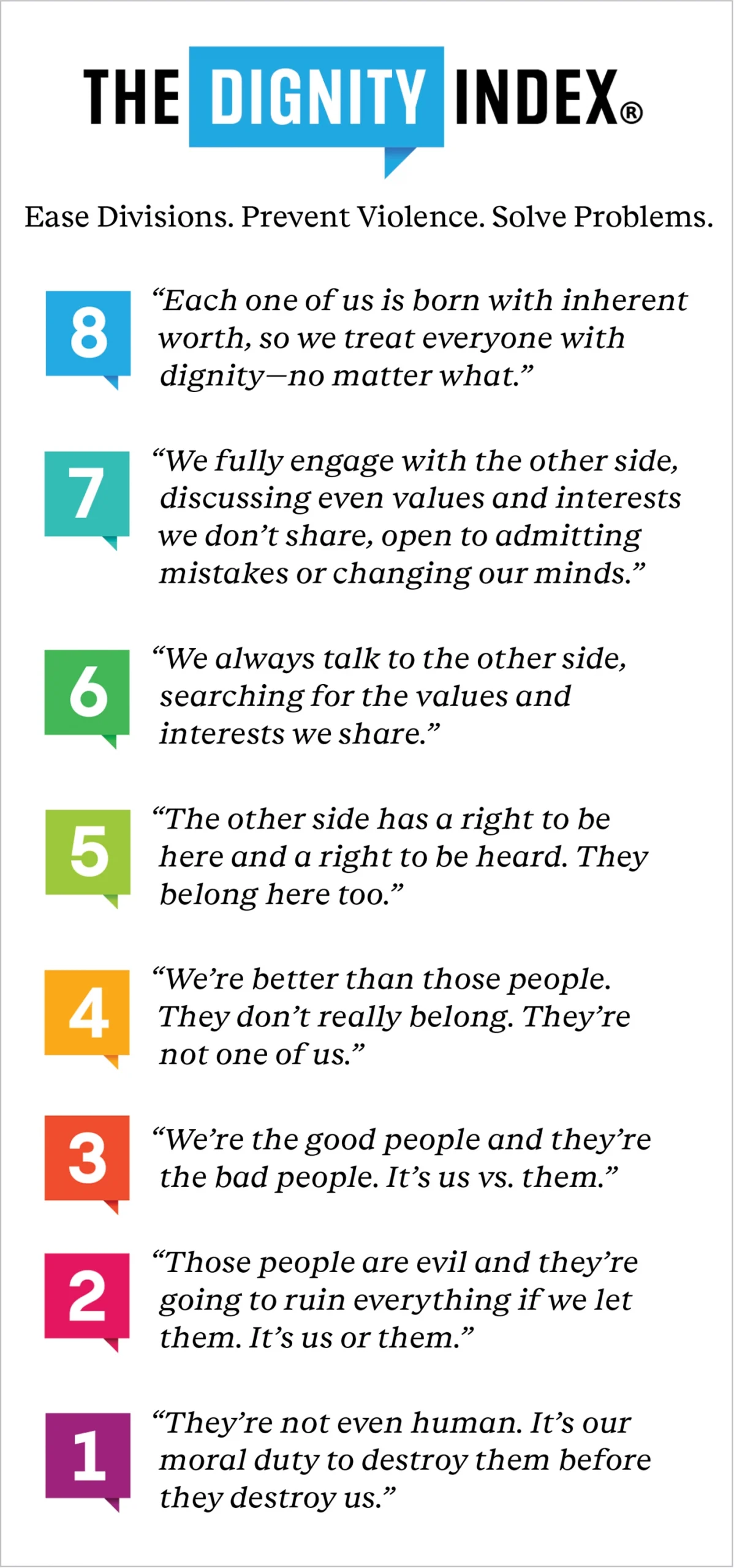

Learning how to disagree better became her goal. Viray and her husband, James A. Viray (BA ’98), moved their family back to Utah, where she began working at UNITE: a nonprofit aiming to increase national unity on a variety of fronts. At UNITE Viray was introduced to the Dignity Index, a tool used to evaluate political speech. At level one of the index, violent words escalate to violent actions; at level eight, those who disagree recognize that we are all united by our humanity and deserve to be offered respect. “We can disagree and retain each other’s dignity in the process,” Viray says. “Treating people with contempt is the problem. Treating people with dignity is the solution.”

The Dignity Index taught Viray to be aware of those natural tendencies in herself, to reevaluate, and to turn from contempt to curiosity. “I really began to see my own contempt and all the small ways it crops up,” she says. “My internal eye roll. My dismissiveness. My labeling or othering.”

This mindset is central to the Disagree Better initiative, where Viray now works as the executive advisor. Working with governors and other prominent citizens, the nonprofit aims to “reshape political behavior by championing healthy conflict as a vital pathway to better policy, increased trust in leaders, and reduced polarization.”

Disagree Better recommends four steps: being curious, listening to understand, respecting opinions, and finding common ground. “The intention of our disagreement should be to come to understand each other and ourselves better,” Viray says.

She notes how political polarization has trained us to think the worst of the other side. But the other side, Viray points out, “wants the exact same thing we do—they want a safe, healthy country.” Recognizing this common goal takes asking others why they believe what they do. “Genuine curiosity is a simple first step,” Viray says.

Listening to understand—not rebut—is the key to respect and understanding, she says. It’s how we improve relationships with friends, family, neighbors, and coworkers.

When we think this applies only to others, she says, is when we need it most. And that’s the point of efforts like the Dignity Index and Disagree Better—we all can be culprits of political polarization. Perhaps, Viray suggests, we could all agree to disagree better.

More: See dignity.us/index and disagreebetter.us.