Rediscovered by the outside world in 1812, much of Petra’s history is only now being uncovered by BYU’s David Johnson and other researchers.

By Michael D. Smart, ‘97

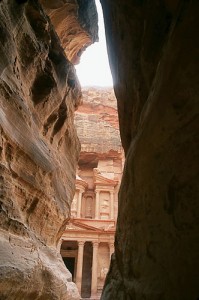

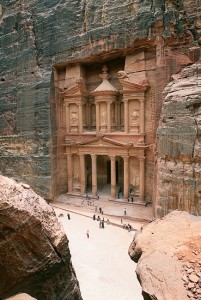

A visitor to the bustling Arab fortress city of Petra on May 19, a.d. 363, would have walked down a mile-long chasm until he rounded a bend and caught a sight that would have stopped him in his tracks—Al Khazneh, a 13-story-tall and 92-foot-wide columned monument chiseled from a red sandstone cliff. After paying taxes there he would have passed several ornate tombs for nobles and kings and then admired a series of palaces—all within earshot of the din generated by two open-air markets where East literally met West. There, Romans, Arabs, Chinese, and Indians all haggled over the prices of incense and spices.

Past the markets, the sand and gravel crunching under the visitor’s feet would have given way to the limestone tiles of the main street, a few hundred yards long. With the blood-red sun setting behind the towering sandstone cliff, he might have gazed up at the red-tiled roof of the gigantic Temple of the Winged Lions before passing through its plastered columns to worship.

Between 9 and 10 o’clock that night, those columns trembled and collapsed, bringing the rest of the great temple down with them, when a powerful earthquake leveled the city, killing many of Petra’s 20,000 inhabitants.

Nearly 1,625 years later, David J. Johnson, a freshly minted BYU archaeologist, cleaned his excavating tools, packed his gear on borrowed horses, and left the ruins of Petra, Jordan, after weeks uncovering the crumbled temple. A week later another group of foreigners—with names like Sean Connery and Harrison Ford—arrived in the remote canyon and borrowed those same horses. They filmed the climactic scene of the 1989 blockbuster Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, bringing Petra’s majestic, rose-colored monuments out of Middle Eastern obscurity and injecting them permanently into popular culture. Western tourists have flocked there ever since.

Johnson, now an associate professor of anthropology at BYU, codirects dozens of researchers excavating the Temple of the Winged Lions. Like The Last Crusade’s protagonist, Johnson is a Utah native who would rather be in the field than the classroom. But at a bespectacled 5’8″, that’s where the similarities end.

“I’m not afraid of snakes,” Johnson states matter-of-factly, having just emerged from an 8-foot-deep pit, snorting goat in tow, with a grateful Bedouin goatherd chattering her apologies for asking him to enter the serpent haven.

Accompanied by more than 40 BYU students over 20-some years, Johnson has spent a dozen-plus summers in Petra and has published extensive scholarly works that describe the temple and the behaviors and religiosity of the city’s residents. This past June found him working with a small group of BYU students on a new project exploring Petra’s suburbia.

David Graf, a University of Miami professor who studies the ancient residents of Petra, is one of many archaeologists who value Johnson’s contributions.

“His diligent and dedicated work at the Temple of the Winged Lions is extremely important for the development of the civic complex at the site,” Graf says of the city’s cluster of public buildings. “The final publication [of Johnson’s research] is something greatly anticipated in the archaeology community.”

Petra’s ancient residents, called Nabateans, had a wealthy culture that benefitted from a location central to the incense and spice trade with the Roman Empire. Their society flourished from about 200 b.c. to a.d. 500 and borrowed elements of art and culture from the Greeks and Romans.

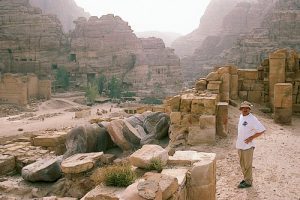

In July 1999 student Melanie M. Teitter, ’00, and Johnson sift through rocks and dirt on Petra’s outskirts in search of artifacts that will help tell the story of the city’s lower and middle classes, relatively unstudied groups. Finds form the former trading city include an ancient Roman coin.

The years in Petra have given Johnson a bond with Petra’s people—past and present—and a gift for envisioning the city in its prime. Starting from the shadows of Al Khazneh, he walks through the ruins, lifting a sun-baked forearm to point out the remains of a stone stage and giant theater that seated more than 3,000 people on 33 rows carved from a cliff. Passing a nondescript, sandy hillside on the right, his eyes widen as he discusses the unexcavated palaces that rest beneath the rocks and rubble. Perched above him on the north side of the valley is the Urn Tomb, one of more than 1,000 monuments carved into the cliffs. The largest monument, known as the Monastery, stands 275 feet tall and is found 1,000 stone steps above the valley floor.

Johnson explains that the foot-wide channels that crisscross the cliff faces were cut by the Nabateans to catch precious rain that fell during the winter months. The elaborate system of channels networked through the city and deposited the water in more than 1,000 cisterns carved out of the rock. Modern-day engineers still marvel at the intricacies of the system that preserved 95 percent of the city’s precipitation.

As he walks through a square lined with concessionaires hawking their wares to the ubiquitous tourists, Johnson is hailed by many of the merchants. “Doctor DY-ood, Doctor DY-ood,” they shout, using the Arab pronunciation of his first name. As he chats with the locals in their Arab dialect, Johnson’s companions are handed cool bottles of soda, compliments of his loyal friends.

“I’ve probably hired and fired half the people in Wadi Moussa,” Johnson says of the people he employs from the nearby town for his digs. “I’ve known most of these men since they were little kids.”

Moving on, Johnson approaches the Temple of the Winged Lions, where he began his career as a pottery-washing graduate student in 1977 and now directs the work. He climbs up the steps and weaves through broken pillars to the inner sanctuary of the temple. Here, he explains, a veil once shielded the altar. His team found the lead “curtain rod” from which it hung.

The artifacts found in the temple demonstrate a “syncretism of cults,” Johnson says. The Nabateans borrowed iconography, motifs, and religious practices from other Mediterranean cultures with whom they were trading. They worshiped a Greco-Roman pantheon combined with their own deities, which were associated with natural phenomena. “Traders from Petra traveling to southern Arabia brought back more than just incense,” Johnson says, noting that their eclectic mix of beliefs and practices extended to such things as economics, politics, and the role of women. It is this cross-pollination of customs and beliefs that most intrigues Johnson and provides the broader framework for his study of Petra.

Just 50 yards from Johnson’s dig site, BYU archaeologist Joel Janetski researches Natufian ruins, 10,000 years older than those Johnson studies.

To better understand some of the Nabateans’ trading partners, Johnson spent this past May working in Yemen at a giant temple, larger than a modern-day football stadium, that legend holds was the “sanctuary” of the Queen of Sheba.

The society’s ties to the Roman Empire eventually became its downfall. When Rome’s economic decline began in the third century a.d., nobody wanted to buy the Nabateans’ luxury goods. Also, as Christianity spread throughout Rome, its leaders banned the burning of incense, causing the frankincense market to bottom out.

Hoping to round out scholars’ understanding of Nabatean culture by looking at its lower and middle classes, Johnson secured a permit from Jordan’s cautious Department of Antiquities for BYU‘s independent project on the outskirts of the ancient city. Each morning he and his students rise with the sun at 4:30 to squeeze in a full day of digging before the searing afternoon heat reaches its peak. To reach their site they hike across a 2,000-year-old stone road that still contains grooves from the chariot wheels of the Romans, who annexed the kingdom in a.d. 106. While the students lug bottles of water in anticipation of the sweat-sapping heat, Johnson, who the students compare to a camel for his ability to work all morning without a drink, walks empty-handed to the dig site.

Much of David Johnson’s research has focused here on th eonce-imposing Temple of the Winged Lions, near the Petra civic complex.

“My main focus is to find information about the ordinary people instead of the elite,” he explains. “So far most research has centered on the temples, the main street, and villas at the core of the city. Without looking at the periphery, it’d be like looking at Temple Square and the Avenues to determine the society of Salt Lake City.”

Johnson found this site when his Bedouin landlord, Daclalla, suggested that he look at a spot removed from Petra’s main thoroughfare. There, Johnson discovered, in addition to the middle-class Nabatean graves he’s now excavating, evidence from a previous settlement populated during the prehistoric Natufian era. In 1997, 1999, and 2001, he was accompanied by BYU colleague Joel C. Janetski, ’65, who specializes in that time period. Together with the help of students, they have studied these two distinct civilizations that lived almost on top of each other, albeit 10,000 years apart.

Sheltered from the elements by an overhanging sandstone wall, Al Khazneh is just one of the monuments that draw tourists and archaeologists from around the world.

While Janetski’s team explores the Natufian settlement 50 yards away, Johnson’s crouches under a rock overhang, using small rounded trowels and brushes to clear sand from human skeletons. After carefully documenting the type and location of the skeletons and artifacts they find, they rebury most of their findings, saving only a few teeth and bones for a DNA analysis they hope will determine the relationships of the deceased.

“We know very little about the man on the street in Petra,” Johnson says. “What were his daily activities? What was his family structure?”

Johnson hopes to answer those questions and more after five or six more seasons at Petra, including the BYU Anthropology Department’s annual field school in 2004. Then he plans to do more research in Yemen, Oman, and possibly even Gaza to tie together his knowledge of Arabian trade routes. When all the pieces are in place, Johnson hopes his research will help rebuild an understanding of a complex culture and stunning city once forgotten in the sandstone canyons of western Arabia.

Michael Smart is a media relations manager for BYU University Communications.