By Doug Robinson

When the call went out that they were honoring the grand old gentleman of BYU athletics, athletes came from near and far.

Jason Buck, the former Outland Trophy winner, drove up from his ranch in Manti. Former quarterback Gifford Nielsen flew in from Houston. Marc Wilson, another former quarterback, made the trip from Seattle. Former major league slugger Cory Snyder was there. So was golfer Mike Reid and basketball player Devin Durrant. In all, some 250 people–administrators, coaches, and male and female athletes from every sport–showed up at BYU one September afternoon to pay tribute to a man who never threw a touchdown pass and never coached a minute. They came to honor a man who washed dirty socks.

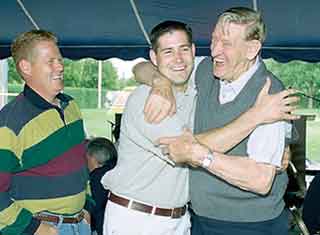

A friend to BYU athletics since 1957, equipment manager Floyd Johnson (right) greets former BYU football players Bryce (middle) and Kevin (left) Doman.

Floyd N. Johnson’s official title is Equipment Manager, but that never quite covered his job description. For more than half of his 80 years, he has worked quietly in a small back room, where the washing and sewing machines whir and the door is purposely left open so athletes must enter the room to get their equipment, the better to visit with them, get to know them, help them.

His way of doing the job wasn’t always welcomed. Shortly after Johnson was hired in 1957, an assistant football coach overheard him giving religious counsel to a player. The coach confronted Johnson a few minutes later.

“I’m going to give you a piece of advice,” the coach said. “You keep your mouth shut when it comes to the Church. You were not hired to be a missionary. You’re nothing but a jock washer.”

Johnson lay awake all that night and decided the coach was wrong; it was his duty to do more than wash jocks at BYU. Johnson decided his job was to protect his players physically and spiritually and to take care of the equipment, in about that order. Ever since then, he has taken hundreds of athletes under his wing. He has prayed with them, cried with them, sent them on missions, set them up with their future spouses, advised them on matters of school and marriage.

“Everybody loves him,” says Buck.

Nobody can resist the tall gangly man with the large ears, big heart, and gentle, warm countenance. The deep lines in his face were grooved not by years so much as by a wide smile.

“He has been like a second father to hundreds of athletes,” football coach LaVell Edwards once observed.

“He affected the lives of every athlete who wore a pair of socks,” gushes Gary D. Pullins, a former BYU player and coach who is now assistant athletic director. “You talk about your experiences with coaches and the thrill of winning and the agony of losing and all that, but then someone says, ‘Do you remember Floyd Johnson?’ Then it’s, ‘Do I remember? He gave me this advice, he helped me with such and such.’ He is the first person I spoke to the morning after I proposed to my wife. . . . When you say, ‘Do you remember Floyd Johnson?’ it chokes you up. He loved us whether we won or lost. . . . He’s there from the time you’re 18 until you’re 25 and a returned missionary with a family. Every athlete in every sport knew Floyd.”

Johnson actually retired in 1984. His boss, concerned that Johnson had been underpaid for years, devised a way to pay him more. If he retired at 65, the boss explained, he could give him a $7,000 bonus. Johnson had never had that much money in his life. “But,” his boss said, “we don’t want to lose you. We’ll hire you right back.”

So Johnson was retired and rehired. For the next 13 years, he received part-time pay and did full-time work until his supervisors were informed he was violating school policy. Johnson said he would retire, but he had one request: Could he serve without pay? For the last two years he has worked six hours a day for nothing “because I love to be around those kids.” He works a morning shift, drives to his Orem apartment to help his wife, Hannah, who has been crippled by arthritis for years, then returns to BYU in the afternoon.

“I have had the best of all lives,” he says.

Most of his working days consisted of 12-hour shifts in the equipment room, followed by hours of service as an LDS bishop. Somehow he and Hannah found time to raise three daughters, one son, and seven Native American foster children, not to mention all those BYU athletes.

“They’re all my friends,” says Johnson.

Johnson’s job of 43 years has been anything but glamorous. He spent hours at a sewing machine, he repaired equipment, he scrubbed football uniforms with his hands and Ivory soap, and he did it all with great earnestness. He consulted a chemist for several months to devise a formula to remove grass stains from football pants. It took him 90 minutes to glue the lettering for Brigham Young University on each track uniform.

“I wasn’t smart enough to shorten it to BYU,” he says.

But he was smart enough to dream up several innovations. In Johnson’s early years, football players belted pads around their hips and then wore pants over them. The problem was the pants slid down and the hip pads rode up, especially when wet. Johnson found a better way. He cut slits in the hip pads and threaded the belt through the pants and pads together. Soon everybody in the country was doing it. Johnson also created a sternum pad and was among the first to develop the four-point football-helmet chin strap that everybody uses today.

Johnson was ahead of his time in more serious matters as well. For decades it was believed that returned missionaries couldn’t play football. “You lost your scholarship if you went on a mission,” he recalls.

But while coaches were telling players they couldn’t serve a mission, Johnson was behind the scenes telling them they could and should.

“The first returned missionary I had at BYU was LeGrand Young,” recalls Johnson. “He walked on to show them a missionary could play. He was as bullheaded as his son (49er quarterback Steve).”

Years later, after BYU became a national football powerhouse, rivals claimed returned missionaries had given the school an advantage.

Through the years Johnson became a favorite speaker, particularly for youth groups. A natural storyteller with a gift for dialogue and detail, he entertained and inspired audiences with stories of BYU athletes–stories he eventually collected into two books (Touchdowns, Tip-offs, and Testimonies, volumes 1 and 2). He also organized and managed an athletes speakers bureau, providing some 300 speakers a year for various organizations.

With his 81st birthday coming up, Johnson says he will continue “as long as I can do some good.” When he finally stops coming to the equipment room, he won’t ever really be replaced. Somebody will hand out equipment, but who will hand out all those other things?

Doug Robinson is a sports columnist for the Deseret News. A version of this article originally appeared in the Deseret News. It is reprinted here with permission.