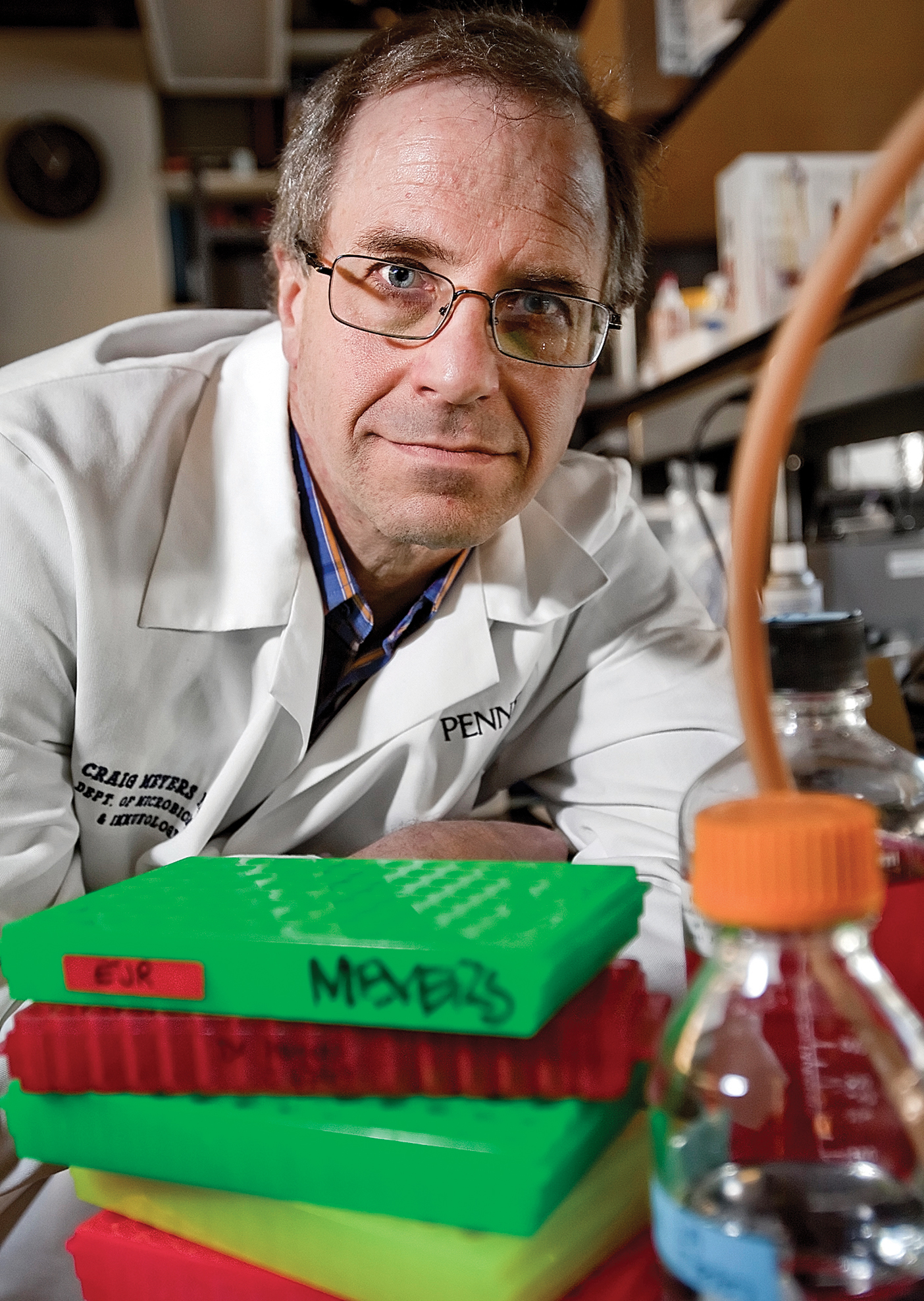

After almost 30 years of study, a microbiology professor discovers a virus that could change the battle against cancer.

Every cancer cell was dead. Examining the tissue culture dish in his Penn State lab in 2008, BYU alumnus Craig M. Meyers (BS ’82, MS ’84) wasn’t sure what had happened. Seven days earlier those same cells had been alive and well. Meyers had directed an assistant to introduce a special virus (called adeno-associated virus type 2 [AAV2]) into the cell lines of cancerous human papillomavirus (HPV) cells and leave it all in an incubator. Now to see them all dead, he suspected they’d made a mistake.

“Our first thought was . . . that there was something wrong with the incubator,” says Meyers, a Distinguished Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at the Penn State College of Medicine. “So we repeated [the test] multiple times, and it happened every time with multiple incubators.”

Since working on a microbiology PhD at UCLA nearly 30 years ago, Meyers has been on the front lines in the ongoing battle against HPV. This sexually transmitted virus leads to the growth of warts on various parts of the body and can result in several cancers, including cervical cancer.

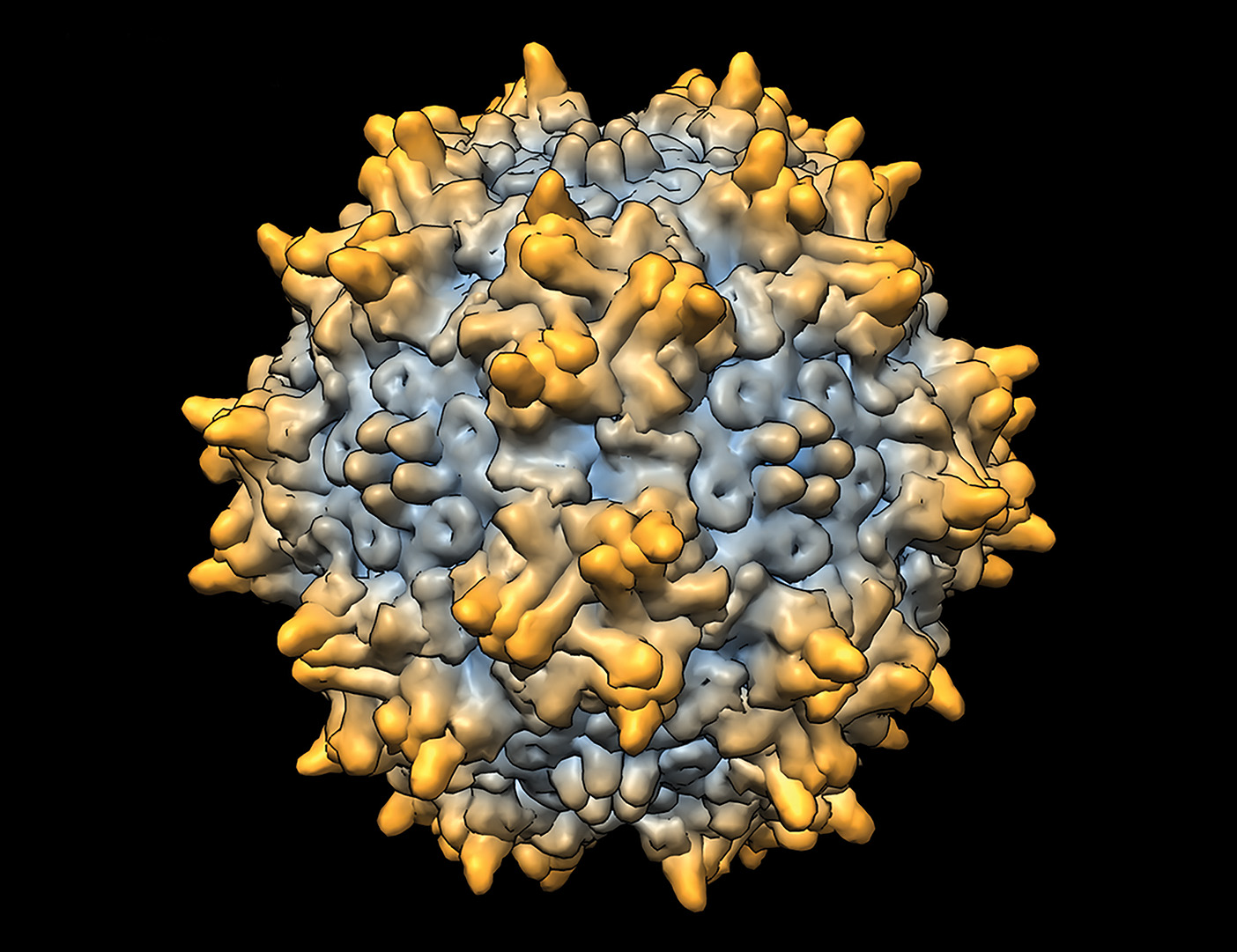

Finding a virus that killed cancerous HPV cells was remarkable because, unlike HPV, there is little known about the AAV2 virus. There had been no crucial need for AAV2 research because, while the virus does infect humans, it has no known negative effect on the human body. However, in that tissue culture dish in 2008, Meyers discovered that AAV2 was somehow causing the HPV cancer cells to kill themselves. He discovered that, in a sense, the cancer cells were being reprogrammed to stop living, a process called apoptosis.

After this shocking discovery and success, Meyers broadened his research. “We . . . collected different cancer cell lines—breast cancer, prostate cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, and mesothelioma cells,” he says. “We tested them all, and [AAV2] worked in them all.”

How and why does it work? “That’s the million-dollar question,” Meyers says. Beginning in 2009, to learn more about the virus and how it might affect one of the more common cancers, Meyers focused his research on triple-negative breast cancer cells. Since starting his breast-cancer testing, he has moved from tissue-culture-dish tests to live-animal tests. The next step will be testing the AAV2 virus on humans.

Human testing is a costly, FDA-regulated process, and Meyers has depended on donations made by organizations and individuals, many of whom have been affected by cancer. For Meyers, it makes the research personal. “If I get a grant from the government, I don’t know those people on an individual basis. . . . But getting the money from donors, you know the people whose life [the cancer] is affecting. You know them. You know their caregivers. You know their family, and so it becomes a more personal connection,” he says. “Unfortunately, in the last year, two of my biggest donors, my biggest supporters, have passed away from breast cancer.”

The loss of friends and supporters like these is particularly painful for Meyers. “It’s rough,” he says, noting how hard it is to watch cancer take its toll on others as the research process plods along. “You second-guess yourself and say, ‘Man, if I was just a little faster; maybe if I had done this or done that,’” Meyers says. “You can’t do that, but you still do it anyway.”

Meyers recognizes that, in the unpredictable nature of the scientific process, nothing is promised to succeed and that it takes time. “Until I can get to this last set of trials, I have to caution people . . . that we don’t have a cure yet and at any step this could just stop working. That’s always the nightmare.

“So far, everything’s been better than we could have hoped for, so we keep moving on,” he says. “If we can get through the next step, then the final big question is will it work in people?”

Meyers, as laser-focused on the goal as ever, isn’t wasting any time to find out.