By Grant Madsen

This mirror is similar to the three mirrors BYU students created for NASA’s IMAGE satellite. Reflected in the mirror are (from left) physics professor David Allred and students Spencer Olson, David Balogh, Matt Squires, and Guillermo Acosta.

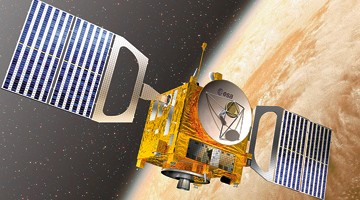

Uranium-coated mirrors fashioned by BYU physics students were launched into space March 25 onboard a NASA satellite. The mirrors will help researchers learn how Earth’s magnetic fields, located beyond the upper atmosphere, respond to upcoming solar storms.

The instruments on NASA’s Imager for Magnetopause-to-Aurora Global Exploration (IMAGE) satellite act like cameras, taking pictures as charged particles streaming from the sun interact with Earth’s magnetic field. Until now, scientists have been able to gather no visual information about the field, which is highly affected by solar activity. The two-year, $154 million mission will allow researchers to capture visual images of the Earth’s magnetic field for the first time.

The launch was timed to coincide with a peak in solar activity, which can disrupt power grids and knock out communication satellites.

“The world depends more and more on satellites for things like cellular phone traffic and geo-positioning technology,” says David D. Allred, a BYU physics professor who advised undergraduates as they worked on the mirrors. “So developing better ways to monitor solar activity and protect satellites is important.”

The BYU team’s three bowl-shaped mirrors act as camera lenses for one of the instruments, the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) imager. Instead of reflecting visible light, the mirrors reflect EUV light—20 times more energetic than visible light—and direct it to an electronic detector that translates it into panoramic pictures scientists can analyze.

“Essentially, the mirrors play a key role in making the invisible visible,” says Allred.

Each mirror is 5 inches in diameter and is coated with eight layers of uranium and seven layers of silicone. This ultra-thin coating—smaller than the width of a human hair—gives the mirrors their unique ability to absorb some types of light and reflect others.

Physics student Matt Squires, 25, from Layton, Utah, says the mirrors are unique. “Before we built them, there were no mirrors that would reflect that high level of radiation—you couldn’t build a silver or aluminum mirror to do the job,” he says. “We had to come up with a new way of doing things.”

Physics students (from left) Olson, Squires, Balogh, and Acosta display one of their mirrors. Coated with uranium and silicone, the mirror reflects extreme ultraviolet rays.

A team of 10 students spent thousands of hours in their lab in the Carl F. Eyring Science Center figuring out how to coat the mirrors—a painstaking process that required lots of ingenuity, experimentation, and luck. Some team members worked to coat the mirrors, others to ensure the coatings were uniform, and others to perform necessary mathematical calculations.

“There was no instruction book to follow,” Allred says. “We were given guidelines as to what the mirrors needed to do and pretty much left to figure the rest out. Students had to invent a new way of using the existing technology to meet the challenge—they’re really champions on this one.”

Charles Curtis, EUV instrument project manager and a physics researcher at the University of Arizona, says the coated mirrors are a critical part of the imager. “The coatings remove unwanted reflections of some frequencies of light and enhance some of the desired frequencies,” says Curtis, who was impressed by the students’ effort on the project.

“I’m sure glad to have worked with them,” he says. “They were a dedicated, hard-working bunch and put in long hours to get the job done.”

And the physics students, all undergraduates when they worked on the project, say it was a learning experience they’ll never forget. The students included Squires, Guillermo Acosta (El Paso, Texas), David Balogh (Santa Cruz, Calif.), Sterling Cornaby (Spanish Fork, Utah), Adam Fennimore (El Cerrito, Calif.), Greg Harris (Ogden, Utah), Shannon Lunt (Mesa, Ariz.), Spencer Olson (Springville, Utah), Shon Prisbey (St. George, Utah), James Reno (Las Vegas), Robby Robinson (Thousand Oaks, Calif.), and Ross Robinson (Thousand Oaks, Calif.). Along with Allred, associate physics professor R. Steven Turley served as an advisor.

Balogh, 25, remembers spending many hours in the lab. “It was frustrating at times,” he says. “But in the end, when I held the mirrors in my hand, it was exhilarating to know they were going up in a satellite.”

Several of the students who worked on the project traveled with their spouses to see the mirrors launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

“It’s nice that they were able to see the fruits of their labors,” says Allred. “It’s not every day that something you built gets shot into orbit.”