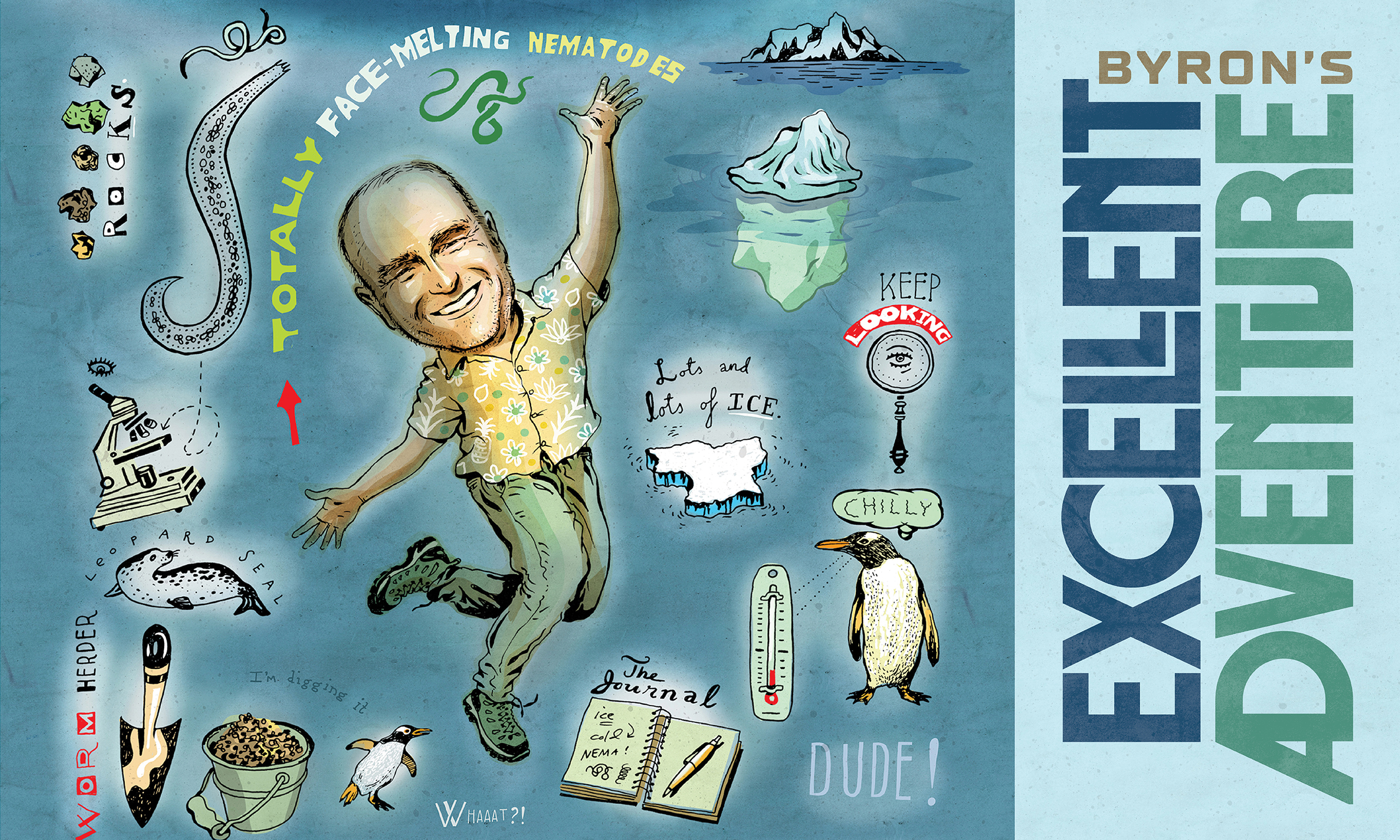

Byron’s Excellent Adventure

UTTERLY UNFORGIVING, nearly all of Antarctica is covered by an ice sheet 2 kilometers thick. Only nunataks, the craggy mountain peaks that spire through the ice fields, break up the blinding-white horizon.

That, and the wardrobe of Byron J. Adams (BS ’93), chair of the BYU Biology Department.

“He’s always wearing a colorful Hawaiian shirt,” National Science Foundation (NSF) Polar Programs director William Ambrose remarks, “a nice touch in the Antarctic landscape.” Adams calls them his “optimist shirts.” One threadbare favorite (now more vest than shirt) is lucky—his go-to when hoping to secure a helicopter.

He’s got the personality—and the lingo—to go with it.

Take the microscopic worms he studies, which he jokes are “the totally awesome megafauna of terrestrial Antarctica.” (Bitty as they are, they’re the largest land animals around—penguins and seals, as marine animals, don’t count.) Or the BYU student protégé who recently memorialized Adams by naming a worm species after him, “He’s a totally righteous dude.” Or the finding in Adams’s latest paper about how phosphorus drives evolution: “It’s just totally face melting.”

His language draws so much attention from students that he felt the need to address it in his Biology 130 syllabus. (Q. Why does Byron always say “dude” and “bro”?) The syllabus gives a long answer about academic versus casual cultural lexicons. His shorter answer: he grew up in Northern California and, he says, “It’s just how I roll.” He can rein it in when needed. “If I’m doing an interview with the BBC and they’re really focused just on my science, I make sure the message gets across,” he says. “But if they want to know how I feel about something, I’ll let it fly, man.”

If Adams sounds like a character, just wait. He’s the guy leading Bob Dylan sing-alongs at Antarctica’s McMurdo Station and talking colleagues into polar plunges with penguins.

Simultaneously, his scholarship is approaching 100 peer-reviewed works, with more than 10,000 citations.

“Byron has a long history of NSF funding,” says Ambrose. Almost 90 percent of the annual proposals to research in Antarctica are rejected; Adams boasts a 20-year streak.

All the while, he’s pulling BYU students up with him, sticking out at top conferences with his entourage of undergrads. Several have even accompanied him to Antarctica.

To meet Adams is like meeting a living Venn diagram—the piece in the middle, the best of both worlds. He’s a surfer dude and a scientist. A mentor and a student. An evolutionary biologist and a deeply convicted member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“I’m totally comfortable traversing both of those areas,” Adams says of biology and religion.

He could go anywhere he wanted, says College of Life Sciences dean Laura Clarke Bridgewater (BS ’89). “Tons of other universities would love to have him. We are just so glad someone of his caliber wants to be at BYU, wants to contribute here, and wants to help BYU students reach their potential in every way.”

Adams just wants students to harness their “superpowers.”

An Unlikely Superpower

After a normal workday in 1969, Walt Adams pulled into the driveway to find his son on the roof. At 3 years old, Byron had climbed up the chimney.

Later there were calls from every teacher. And calls from the neighbors: “Your kid’s throwing dirt clods into my pool!”

“I was just that kid,” says Adams. “I had—I still [have]—massive ADHD.” They tried Ritalin, but his parents felt the drug made him someone he was not. “My dad was like, ‘Nope. We’re going to move out of this place and let this kid run feral.’” And so they traded suburban Davis, California, for rural Susanville, California, and a home that backed up to the mountains. Five years on they moved to a nearby farm, where there were fences to fix and cows to milk.

“They allowed me to be who I was,” says Adams, “but they also helped me channel that energy into something that was positive.” In an effort to be self-reliant, the family also grew their own food.

Kids would look at his lunchbox, perplexed. “They had, like, these weak-sauce baloney sandwiches with white bread or whatever,” says Adams. His was on homemade wheat with pig brains or cow tongue for meat and freshly pickled beans. “I was proud of it,” says Adams.

The family spent holidays and weekends at the ocean, where his dad and uncles—among the very first recreational scuba divers—always attracted a crowd. In scuba gear pieced together from the Army Navy store, they would disappear into the water, returning with eels, crabs, and urchins. “It was like he’d gone out to space and brought back a ship full of aliens,” says Adams. Even as a kid, he was enchanted: “It was always going to be biology,” he says of his future path.

With farm responsibilities and an ocean to explore, along with coaching from his parents, his troublesome traits became his “superpowers.” The boundless testing of limits, the ability to pivot endlessly, and hyperfixation on a project now enhance his science. “I don’t think of that as debilitating anymore,” he says. “I think of it as a gift.”

Dude, I Could Do This

That’s not to say school wasn’t a struggle.

“I wasn’t a very good student,” Adams admits. “But I was a really good scuba diver.” By his junior year at BYU, he had logged more than 200 dives.

Because of that skill, BYU professor Lee F. Braithwaite (BS ’59, MS ’62, PhD ’70) allowed him to join a student trip to Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Station, where Adams collected specimens that would inhabit Widtsoe Building fish tanks.

Prior to that trip, Adams says, he was just a dumb kid from a Podunk town. Braithwaite flipped that on its head. “He made me believe that I could actually do science,” he says.

Now Adams shares his early BYU transcripts—the semesters he tanked—with his students. “A lot of our students get here and think this whole university is smarter than they are, and it’s complete baloney,” he says. “Sometimes they just need a faculty member to show them what their real potential is.”

It’s the kind of mentor he has tried to be for 100 research students and counting.

“He treats you like a peer,” says former lab employee Timothy S. Davies (BS ’07), now an ER physician in Phoenix. Davies never felt like a grunt; Adams wanted Davies to opine and to pursue his own questions and to always show him the data.

At once demanding and down to earth, he’s both lab leader and confidant. “He’s so friendly and casual, he can talk to people about anything and they’ll listen. He’s disruptively innovative,” says Davies.

Especially in the classroom. Some days Adams shows up in a full Yeti costume; others he’s rewarding answers with whatever happens to be in his pocket. “One time it was two Taco Bell hot sauce packets,” says Davies. Anything to keep students engaged.

“Sometimes I wonder what’s going to happen,” says BYU biology professor Jerald B. “Jerry” Johnson (MS ’95), who tag-teams Biology 130 with Adams. Suffice it to say, few students sleep in class. In fact, across all metrics, their approach has an edge on traditionally taught sections.

One time Johnson was at the lectern teaching about biochemistry. “All of a sudden I’m smelling waffles. And Byron’s all, ‘I’m making a little magic up here, Jerry.” He’d found a way to connect waffle ingredients to the chemistry concepts.

It sounds zany, but Johnson emphasizes that Adams is just as likely to get serious—even reverent—in the same hour. And he’s not afraid of the hard stuff.

Students come with real questions that they hope to have answered in an honest way, says Johnson. “Byron doesn’t shy away. . . . He doesn’t want them to leave BYU without working through those topics in a faithful, covenant-committed way.”

“I am deeply committed to how BYU rolls in terms of the integrated approach to faith and reason,” says Adams. “That’s a huge, important part of an education.”

Finding Nematodes

The best student tribute to Adams came in February, when he was made the namesake of a parasitic worm: Steinernema adamsi.

And Adams couldn’t be more tickled.

Adler R. Dillman (BS ’06), a professor of nematology at UC Riverside who discovered the new species, says naming it after his BYU mentor “was a no-brainer. . . . Byron introduced me to these little guys; he lit the flame burning so brightly in my heart for nematodes and their biology.”

It’s hard not to convert when you hear Adams talk about microscopic worms.

“Nematodes, man, they’re your best friend,” says Adams. “Like, everything that humans need to survive on this planet is provisioned in part by these organisms that live in the ground, and we’re just walking around on them all day.” The most abundant animal on the planet, nematodes exist even in your colon—even in desolate Antarctica, he says. “They’re inspiring in how they can persist.”

Among the species his team has described are masters of cryogenics—worms that can survive suspended in ice for thousands of years. Others go the freeze-dried route, reanimating when their habitat is wet again. “Every time I observe it with my own eyes, I still get a big smile on my face. I’m like, ‘Dude, I just pulled that thing out of the -80 freezer, where it’s been since 1993, and it’s wiggling around right now. Like, wow.’”

It’s the stuff of sci-fi. “If we could apply that trick to human organs, we could just freeze them and keep them on the shelf until a recipient’s ready,” he says.

His work goes far beyond describing species. Using worms, Adams and his colleagues are probing questions of evolution, glacial records, climate change, and life on Mars. Adams is also the first—on this planet—to find nothing. As in lifeless soil. “Finding nothing was awesome,” he says.

But Adams is most stoked about his most recent paper. Decades ago, a few famous biologists postulated that phosphorus drives everything in an ecosystem—all the way up the food chain. But no one could figure out a way to underpin this with data. Antarctica proved the perfect laboratory, with its simple ecosystem featuring phosphorus-rich and phosphorus-deficient valleys. The same worms lived in each, but the worms in the latter, he found, had altered genomes.

Adams, with the help of students, proved it again back at BYU over a decade, nurturing 345 generations of Plectus murrayi in petri dishes.

“I felt like I proved Newton right or Einstein right,” he says. “To me that’s just totally face melting.”

Circle of Life

Worms—and lizards—feature prominently in Adams’s Woodland Hills, Utah, home.

His wife, Marcella “Marci” Shaver Adams (BS ’94), is a herpetologist—a lizard lover. Nematodes and lizards combine in the couple’s stained glass and commissioned artwork among other “nerdy stuff,” says Byron. Among the specimens, there’s a cougar skull in the living room.

Growing up with two biologists for parents “was like ‘The Circle of Life’ from The Lion King was always playing in the background,” says daughter Liesl Adams, who is presently serving a mission in the Philippines. The biology hype extended to the dinner table. “Anytime we had asparagus, we had the conversation about how it has been [around] since the dinosaurs were walking around,” says Marci, who also teaches biology at BYU.

For about two months—every year for the last 20—she is a single parent while Byron works in Antarctica. When Byron first got invited, he thought she’d nix it. “Not a chance!” she told him. “You’re going, and if you’re not, I will!” (She has joined the team twice.)

It comes at the cost of Christmas together; the austral summer, when the sun shines in Antarctica, falls during Utah’s winter. And he missed the birth of Liesl, who arrived early via C-section. Marci remembers the doctor taking Byron’s satellite call just before making the first incision: “The doctor picks up the phone and says, ‘What? From where?’”

Byron feels lucky, despite the trade-offs.

Stepping out onto the Antarctic canvas, he says, “it’s like stepping into the Creation. I put my foot down in places where I am the first set of human eyes to see this. It’s like seeing the world prior to humans being on the planet.”

“I want to be awake for all of it,” he continues—he’s even written wonder into the protocol for collecting soils. “Step 6: Look up, take a look around, take a deep breath, appreciate your place in all of this.”

It’s why he sleeps maybe three hours a night while he’s down there and why, with his three kids, he can’t pass up a single flower. It’s why he’s eaten scallops while scuba diving—to see how it would taste to a fish. Or kissed a stinging anemone (the lips have more nerve endings, he explains). “It sounds like the dumbest thing, but I want to know what that’s like. . . . If it’s unique in all the world, I want to sense that, to feel it.

“It gives me a greater appreciation for our role as stewards in the world. . . . I want to describe it, to help others to understand it, to protect it, and to share that knowledge with others.”

Wild Optimism

The weather at Cape Hallett was miserable, even by Antarctic standards. On top of that, the research team’s work was stymied when they learned they needed additional permits to study so close to the Adélie penguin rookery, 40,000-strong. And no plane dared risk rescue in the storm.

“We were stuck,” says J.E. “Jeb” Barrett, a Virginia Tech biology professor and member of Adams’s long-term ecological research team. “You couldn’t even go out of the tents, it was that awful.”

When they emerged three days later, they discovered that the storm had broken up the ice on the bay and blown it out to sea. And that gave Adams one of his quintessential wild hairs. “It’s just the kind of thing that Byron does to juke up morale,” says Barrett. Why not go for a swim?

“I was, like, ‘Hey, man, with all that ice gone, this looks like a really nice beach,’” Adams retells it. And so he convinced a colleague to join him for a polar plunge—in water with penguins. Which also means, Barrett points out, water with leopard seals.

The point, says Barrett: Adams makes his own weather. Like the time his luggage got lost and he had to make due with items from the “Goodwill of Antarctica” bin. Adams turned it into a fashion show. “It was three weeks of the most ridiculous outfits,” says Barrett.

“With Byron, it’s like anything is possible,” says Ian Hogg, a biologist at Polar Knowledge Canada. Once, near the Shackleton Glacier, the team searched for a particular insect to no avail. When the helicopter was ready to leave, no one could find Adams. He wasn’t going to leave without the samples. “I have this brilliant picture of him running up this steep hill,” says Hogg. “He jumps into the helicopter and casually tells me, ‘I found them.’” Another time, Adams about froze his fingers off collecting samples when no one else on the team would venture out. “I still have all my digits,” Adams says, wiggling them proudly—even though his hands have never been the same. “We got two really nice papers from that data.”

His positivity is pervasive at BYU too. “Larger than life is the phrase I would use,” says John M. Chaston (BS ’05), one of Adams’s mentees, now a BYU professor of plant and wildlife sciences. “He’s such an example of approaching your work and your life with joy and of really celebrating those things you toil for.”

Chaston spent a year in Adams’s lab trying to figure out how to extract DNA from these microscopic worms, failing again and again. When Chaston finally succeeded, Adams made a huge deal. “He was all, ‘That’s beautiful! We’ve got to put that up on the door of the lab! You’re going to get dates!” Up it went with Chaston’s phone number. A week later someone had written her number in response. You know how this BYU story goes—now they’re married.

Up for All of It

Enthusiasm comes down to feeling lucky, says Adams. “Even just to be here, to be in a body, right? Remember? We were totally stoked. We were like, ‘Yeah, man, put me in a body. I’m going to go down there and I’m going to show you I can do this.”

He wants to sense it all—even if it comes at the cost of a tussle with a giant Pacific octopus. “What’s worse to me would be spending the rest of life not knowing what was behind that rock.”

And he finds inspiration in it all, be it parasitic worms or a raccoon recently at his bird feeder. “I was struck with awe and wonder just watching that little dude try to figure stuff out,” he says. Every biological phenomenon, he says, “has part of the wonderful in it.”

And he is up for it—all of it—even in the harshest, driest place on earth. Run a marathon in Antarctica? Regularly. Endure howling winds in sub-freezing temperatures eating expired graham crackers, the backup rations stored at this field hut? Sure. Share his religion and beliefs under a big Antarctic sky? All the time.

“The people I work with are very different from me,” he says. “We have really different perspectives.” But ask him what he anticipates most about the frozen, desolate place he returns to year after year, and it’s being there, with colleagues he loves, wholly immersed in their science, no cell phones, no distractions. “None. There’s only the Antarctic landscape and our imaginations.”

Feedback Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.