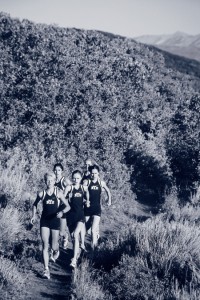

Winning national championships in 1997, 1999, and 2001, the BYU women’s cross country team has helped raise women’s athletics at BYU to a new level of distinction.

By Peter B. Gardner, ‘98

FEB. 20, 1997. FIFTY-FIVE METERS. FIVE HURDLES. FIVE SPRINTERS. 00.00 SECONDS ON THE CLOCK.

A single shot cracked through the air, and as the racers burst out of their blocks, the electric clock at the other end of the track came to life—the tenths and hundredths of a second flickering in a blur as the runners flew over hurdles and the seconds mounted up, freezing at 7.29.

When she first saw it, the unofficial time didn’t bear much significance for BYU‘s Tiffany Lott, ’98, now Tiffany Lott-Hogan, a BYU strength and conditioning coach. She knew she had run well and even hoped the time, when adjusted to a final mark, would be a personal best. But only one one-hundredth of a second was added, making her official time 7.30.

“I thought, Wow. That’s a personal record,” remembers Lott-Hogan, who still hadn’t caught on.

But then the commentator announced that she had set a meet record, a collegiate record, an American record, and a world’s best. Tiffany Lott had just run the indoor 55-meter hurdles faster than any other woman before her or any other woman since. Lott’s 7.30-second 55-meter hurdles is just one stat among thousands that have been posted by BYU women’s teams and athletes over the last 30-some years as BYU has become a powerhouse in women’s sports.

Lott’s 7.30-second 55-meter hurdles is just one stat among thousands that have been posted by BYU women’s teams and athletes over the last 30-some years as BYU has become a powerhouse in women’s sports.

BYU women’s teams have taken first or second place in 77.7 percent of their conference finishes since the 1974–75 season. The women’s track team hasn’t taken less than first place in an outdoor conference championship in 20 years. BYU female athletes have received more than 350 All America citations in 11 sports. And the women’s cross country team has reached dynasty status, winning three national championships in the past five years. The numbers, as they say, don’t lie.

But administrators, coaches, and athletes alike attest that the remarkable gains in women’s athletics at BYU are much more than just a numbers game. It’s about women realizing their individual potential and, at the same time, becoming some of the most visible representatives of BYU ideals. In the words of the Cougar fight song, it’s an unfolding victory story—a win for women’s sports, for BYU, and for individual athletes.

MAKING THE TEAM

On an average day of competition, gymnast Margaret Greenwood had little time to celebrate her all-around score from an early morning meet. She was too busy lacing up her basketball shoes as she prepared to compete in the tournament that would begin at noon. Just after that finished, she would make a quick change in attire to compete in an afternoon swim meet. On another day it might be tennis then track and field then volleyball.

In all, Margaret Greenwood Blake, ’67, participated in 12 sports during her years as a Cougar in the mid-1960s, dominating in tennis and gymnastics while receiving honors in basketball and volleyball. She and her doubles partner in tennis were the first BYU women to participate in a national intercollegiate championship tournament.

Since women’s sports during this “sports day” era were limited to just one day of competition in the fall, winter, and spring, athletes like Greenwood had to make the most of their minimal opportunities.

“It was exhausting but fun,” remembers Blake, noting that this regional competition usually followed an all-night ride on a crowded van. “Because we were representing BYU we would have to wear a dress, hose, and heels for the entire trip. You can bet we wore shorts under the dresses,” she jokes. What stands out to Blake are the fun times had with athletes and coaches despite less-than-perfect circumstances.

Along with the long drives, she and other athletes from the period recall paying for their meals, sleeping at Church members’ homes, and not having uniforms. “We had to provide our own shoes and racquets and even tennis dresses, which we had made,” Blake says of a trip to the national tournament at Stanford.

More than anything, women athletes of that era were fighting a mindset that said they didn’t belong in sports. Socially, they were stigmatized as “tomboys” and were often overlooked by men in the dating game.

Their plight certainly wasn’t helped by the American Medical Association’s official stance against female involvement in sports, says Lu Wallace, ’56, former longtime administrator of women’s athletics at BYU. “It wasn’t until the ’60s that they felt women could run a mile without injuring themselves,” says Wallace, who grew up on a farm and played high school basketball in Driggs, Idaho. “I’d seen women work in the fields with men and could never understand why they thought it would be detrimental for women to be active.”

The reversal of the AMA‘s position in the mid-1960s is emblematic of the progress women athletes began making as the fitness craze set in. With this momentum, women college coaches and administrators banded together to expand play to formal seasons with conference championships; by 1970 there were six new national championships (there had already been national championships in tennis and golf sponsored by the individual national sports organizations).

BYU found immediate national prominence in volleyball and gymnastics, hosting the national championships in gymnastics in 1970 and volleyball in 1973 (taking second place) and 1977.

Welch Suggs, the senior editor for athletics at the Chronicle of Higher Education, was curious about BYU‘s dominance over 30 years, noting that it is rare for a conservative, religious school to be progressive in women’s sports. “I don’t get why there is so much enthusiasm for women’s sports, with the Church and with the conservative atmosphere,” he says. He looks to the early leadership provided by BYU‘s women coaches and administrators.

“If they were going to coach,” says Wallace, “they wanted to be successful.”

“We had high standards,” says Elaine Michaelis, ’60, BYU‘s current women’s athletic director and recently retired volleyball coach of 40 years. “When something happened nationally that made opportunities better for women, we were right there to jump in and make recommendations to the administration, and the administration was very supportive.”

Along with formal seasons and national championships came the creation of the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW), in which BYU coaches and administrators played a formative role, serving on committees for ethics and eligibility and for the development of individual sports. The most significant change came in 1972, when congress passed Title IX, which mandated equal treatment for men and women athletes.

Despite these developments, progress in funding, scholarships, and facilities came only gradually. “There were giant strides made over the next two decades,” says Wallace, “but they were small steps at a time.”

Transitional athletes like Karen Curtis Lamb, ’79, one of BYU‘s first female athletic scholarship recipients and the newly named women’s volleyball head coach at BYU, remember getting by on a meager budget. “The worst part was the gym suits we worked out in,” says Lamb with a look of horror as she recalls the snap-up, one-piece P.E. issue. “You had to get them really big or it was hard to get your arms above your head.”

But rather than complain about what they lacked, coaches and players remembered what had been and felt grateful for advances when they came. “I thought it was the big time,” says Lamb.

“Women’s sports had gone from play days to actual organized competition.”

Elaine Michaelis (left) and Lu Wallace, as coaches and administrators, helped raise women’s athletics at BYU from obscurity to national prominence.

Seizing every opportunity that has come over ensuing decades, the women’s program at BYU is little sister no more, having earned its place at the training table through a stunning array of individual and team successes. From swimmer LeLei Fonoimoana’s 11 All-America citations (1976 to 1981) to volleyball’s 1993 Final Four appearance (the first time a BYU team had made it to an NCAA Final Four) to cross country’s national championships (1997, 1999, and 2001), BYU‘s women athletes have been a major force in establishing the school’s national sports reputation. In fact, BYU‘s 17th-place finish in the 2000–01 Sears Director’s Cup, which is awarded to the school with the best overall athletic program, would have improved to eighth had only women’s scores been counted. Rising with the tide of women’s sports, the Cougar women have created one of the most successful women’s athletic programs in the country and a reputation for winning—and winning in the right way.

Rising with the tide of women’s sports, the Cougar women have created one of the most successful women’s athletic programs in the country and a reputation for winning—and winning in the right way.

WINNING FRIENDS

After Brenda Peterson, ’74, slammed the ball down to the shining hardwood on the opposite court, her team erupted in celebration. The referee signaled a point for the Cougars. The early-round match of the 1971 national volleyball tournament in Lawrence, Kan., was over. But Brenda knew her finger had glanced the net.

The official stared in shocked silence as Brenda explained that she had committed a foul. “I know it was hard for you to see. It was a close call. I just wanted you to know I touched the net, and they should get the ball,” she explained.

“There was this big sigh of ‘Oh, no,'” recalls Peterson, who was captain of the basketball and volleyball teams from 1969 to 1973. “At BYU we were always taught to make honor calls.”

After a moment’s consideration of what to do in this unfamiliar situation, the official signaled a side out to the other team and resumed the match, which the Cougars eventually won. Afterward, Latter-day Saint missionaries with investigators in the audience came to talk with players about what they had seen.

Because of Brenda’s honor call and others like it throughout the tournament, teams began to play differently against BYU, often making honor calls of their own, says Michaelis.

Karen Lamb, BYU’s newly appointed head women’s volleyball coach, was one of the first female athletes to receive an athletic scholarship at BYU.

Soon after the tournament, when Michaelis attended an early AIAW board meeting, the honor calls came up. “The board came to the conclusion that it wanted to increase this kind of play,” she says, noting that an amended version of the policy the board drafted encouraging honor calls remains in rule books today.

“I’ve always had the philosophy ‘I don’t want a point I didn’t earn,'” says Michaelis.

This standard of integrity has become a hallmark of Cougar women’s play, and honor calls haven’t been limited to the volleyball court. After an honor call at a softball game, the home-plate umpire toldBYU‘s catcher he had never before seen anyone give information on a call that would affect her team adversely. Coaches also stress sportsmanship. “We win with dignity,” says Lamb. She adds with a laugh, “We try to lose with dignity. We don’t like to lose, but we still try to put on a good face and be gracious.”

Coaches also stress sportsmanship. “We win with dignity,” says Lamb. She adds with a laugh, “We try to lose with dignity. We don’t like to lose, but we still try to put on a good face and be gracious.”

Peterson, who later played on the U.S. University World Games volleyball team, says BYU teams were respected for their standards. “BYU was looked on as a team that plays with integrity. We made friends wherever we went.”

Making friends, according to BYU president Merrill J. Bateman, is exactly what Cougar athletes should be doing. An ardent supporter of BYU athletics, he has encouraged school teams, which are primarily made up of Latter-day Saint players, “to be among the very best.” Competitive success can’t help but gain positive media attention for BYU and the Church before a national audience.

“Our mission,” says Michaelis, “is to be representatives of the Church and have people consider that this is something unique, something special that they may want to embrace someday.” Coaches regularly remind players of their ability to help create positive impressions of BYU and the Church.

An unexpected opportunity for BYU to shine under the national spotlight came in March, when women’s basketball guard Erin L. Thorn, ’03, shot a blistering 62.5 percent from the field and dropped seven three-pointers to help the Cougars upset the higher-ranked Florida Gators 90-52 and advance beyond the opening round of the NCAA tournament for the first time.

Media attention focused sharply on BYU‘s decision not to use their Sunday practice time to prepare for the game against Iowa State on the Cyclones’ home court the next day. In a press conference, reporters asked players and Coach Jeff Judkins if they felt they would be at a disadvantage for not practicing on Sunday. Freshman forward Danielle Cheesman, ’05, responded that she didn’t think her team would be worse off, noting that they would spend the day attending Church, presenting a fireside for the local stake, and reading scriptures. “We’ll be better off resting and doing the things we do on Sunday,” Judkins added.

It also came out in the press conference that if the Cougars made it to the championship game, it would have to be rescheduled according to NCAA policy since the Cougars would not play on Sunday.

News of BYU‘s determination not to practice or play on Sunday made headlines in dozens of papers nationwide, including USA Today. “It was all over in the media that here is a Mormon school living by its standards,” says Michaelis, “that it could be to their disadvantage, but they believe in it strongly.”

The team repeated the improbable when it went on to overcome a late eight-point deficit and defeat the home-court favorites 75-69 in front of more than 7,600 Iowa State fans. “Our team played hard and clean and fair,” says Judkins. After the game a parent of an Iowa State player told him, “We don’t like losing, but to lose to you guys was not that bad.” The next week when the Cougars lost a close game to Tennessee in the Sweet 16, many of the Iowa State fans had turned up to cheer the Cougars on.

After the game a parent of an Iowa State player told him, “We don’t like losing, but to lose to you guys was not that bad.” The next week when the Cougars lost a close game to Tennessee in the Sweet 16, many of the Iowa State fans had turned up to cheer the Cougars on.

“More rewarding than winning was to see our players handle themselves and represent the Church very well,” says Judkins. “They are far better off the court than they are on the court.”

“They are who they are, and all they have to do is be that,” says Michaelis. “They just are naturally very good young people.”

MORE THAN THE RACE

BYU women’s soccer coach Jennifer Rockwood needs more shelf space. That or less-successful teams. In only seven years since soccer became a sanctioned NCAA sport at BYU, her teams have won four conference championships and placed in the top 20 four times, and the walls and shelves of her office below the Smith Fieldhouse stands are crowded with conference and national trophies and plaques.

Tiffany Lott-Hogan, a BYU strength and conditioning coach, still holds the world’s best she set in the indoor 55-meter hurdles in 1997 as a BYU track star.

A relentless competitor, Rockwood easily recalls the details of winning each one of them. And she still begrudges what she remembers as a bad call that cost her team a conference championship one year. “We’re still bitter about it,” she says, smiling.

As competitive as she is, Rockwood regularly wanders from records and scores as she talks about her teams. She mentions with some satisfaction that several former players and their husbands had babies this spring and summer.

“Soccer is important in their lives, but it can’t be the most important thing,” she says. “We want to motivate them and make them realize that they can become their best in everything, not just at soccer, but academically, socially, and spiritually.”

Judkins, a former NBA player, agrees. “Winning games is great, but when it all comes down to it, it’s not the most important thing that we’re here for.” In fact, winning takes fourth place in Judkins’ list of goals for his athletes, following graduation, preparing for family life, and being examples for BYU.

Maren Hendershot Brown, ’00, a former first-team All American and a current member of the San Jose Cyberays professional soccer team, says being a BYU athlete provided opportunities for her to grow—on and off the field. “Those were some of the coolest experiences,” she says of the firesides the team would present to youth gatherings during road trips, “to be able to bear your testimony to all these kids you don’t know, but also to your teammates. We also would get up early in the morning sometimes to do baptisms at the temple. Those are things that shape you as a person.”

Like Brown, former BYU women athletes who describe how sport has shaped them tend to use phrases like determination to succeed, learning not to give up, ability to work hard, losing gracefully, finding balance in life, teamwork, and empowerment to achieve, noting that the influence of athletics extends into work, motherhood, Church callings, and other aspects of their lives.

“Athletics have always been a huge part of my life,” says Blake, who still competes in tennis and whose eight children have all participated in sports. “The lessons I’ve learned have been good for everything else I’ve done and in rearing my children.”

Blake and other athletes know that team finishes, personal bests, shot percentages, and batting averages are eventually just two-dimensional figures on paper or electronic blips in computer databases. The real value of the advances in women’s athletics over the past 40 years, says Lamb, is in the opportunity for women to reach their potential. “Athletics teaches a lot of valuable lessons that we would be missing out on if we didn’t have it.”

With so much emphasis on personal growth, it’s little wonder that, after coming from out of nowhere to beat the Stanford Cardinal by the slimmest of margins and win their first cross country national championship in November 1997, the BYU harriers spoke as much about their relationships and what they had learned as they did about the championship.

The end of Margaret Blake’s prolific BYU sports career hardly marked the end of athletics’ influence in her life. She still competes in tennis, and her husband Karl B. Blake, ’68, and their eight children all participate in sports.

“The closeness of this team is what distinguishes us,” said Sharolyn Shields, now Sharolyn Shields Thayer, ’01, after the victory. “We all care about each other so much, and we worry about how each person does.” Having committed to each other to train their hardest and perform their best, they were fueled by a desire not to let their teammates down.

Caisa J. Monahan, ’00, believes their unity made victory possible. “We had a major advantage over all the other teams because we had a fireside, we had a team testimony meeting, and we are so much closer as a team. Those are my favorite parts of the weekend, maybe even more than the race.”

A CENTURY OF WOMEN’S SPORTS

1899

Brigham Young Academy’s first intercollegiate competitive sports event for women is a basketball game against the University of Utah.

1911

Women’s tennis is organized.

1923

Women’s swim team is organized.

1932

BYU student Vera H. Conder, ’34, becomes the first Utah woman to try out for the U.S. Olympic Track Team.

1939

Play days are organized for women’s athletic competitions among Utah schools.

1946

Play-day competition is expanded to include schools from Wyoming and Colorado as well as Utah. The Collegiate Women’s Physical Education Association is organized and governs the Intermountain competition.

1966–67

The first uniforms for a BYU women’s team are purchased.

1967

The Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (CIAW) establishes national championships. Wallace is named the first Intermountain region representative to the CIAW.

1969–70

National championships are inaugurated in badminton, golf, gymnastics, swimming and diving, track and field, and volleyball; the women’s volleyball team is the first to be invited to a national championship tournament.

1970

BYU hosts the national gymnastics championship.

1971–72

The Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) is organized and replaces the CIAW; BYU coach Elaine Michaelis becomes Region VII’s first representative to the AIAW council.

1972

Congress passes Title IX of the Educational Amendments. Lu Wallace becomes BYU’s director of extramural sports (later the administrator of women’s athletics).

1973

BYU hosts the national volleyball championship and takes second place; BYU would host it again in 1977.

1974

BYU awards its first women’s athletic scholarships to women athletes. BYU women’s teams join the Intermountain Athletic Conference (IAC).

1976

Earlene Durrant becomes BYU’s and Utah’s first female certified athletic trainer and works with BYU’s women’s teams. BYU appoints Ellen Larsen as its first women’s sports information director, one of the first five women in the nation to receive this position.

1976–77

Tennis player Karen Kennington Jeppson, ’82, and swimmer LeLei Fonoimoana Moore, ’81, become BYU’s first female All Americans.

1978

Themis Zambryzcki, ’81, (indoor pentathlete) becomes BYU’s first female athlete to win a national title.

1979–80

BYU’s women’s programs finish seventh in the first annual All-Sport Championships, sponsored by the American Women’s Sports Federation.

1980

Leona Holbrook, longtime physical education instructor and women’s sports administrator at BYU, becomes the first woman inducted into BYU’s Athletic Hall of Fame.

1982

AIAW dissolves and the NCAA becomes the only governing organization for Division I intercollegiate athletics. Lu Wallace chairs a meeting with six Division I schools, creating the High Country Athletic Conference (HCAC), a women’s conference that would align with the NCAA; BYU leaves the IAC, having taken first or second place in 62.5 percent of the conference finishes.

1985

Margaret Greenwood Blake, the first female athlete to represent BYU at a national championship (tennis), becomes the first female athlete to be inducted into BYU’s Athletic Hall of Fame.

1990

Female athletes join the men in the Western Athletic Conference (WAC); BYU leaves the HCAC, having taken first or second place in 81.9 percent of the conference finishes.

1993

The women’s volleyball team becomes the first BYU team—men’s or women’s—to reach a final-four bracket in an NCAA tournament; Elaine Michaelis becomes the first female coach in the nation to lead a volleyball team to an NCAA final-four bracket.

1994

Soccer is added as the 10th women’s sport at BYU. Lu Wallace retires after 23 years as BYU women’s athletics administrator; Michaelis replaces Wallace.

1995

Tennis coach Ann Valentine is named ITA/Wilson National Coach of the Year, the first BYU women’s coach to receive such an award.

1995–96

Six of the 10 women’s teams finish in nation’s top 20: cross country, fourth; gymnastics and tennis, 12th; indoor and outdoor track, 15th; and volleyball, 17th.

1997–98

Cross country wins the national championship; four other women’s sports finish in the top 10 nationally: outdoor track, third; volleyball, fifth; tennis, ninth; and indoor track, 10th.

1998–99

BYU is ranked 12th in the Sears Director’s Cup—its best placement.

1999

Women’s softball becomes an intercollegiate sport at BYU, and cross country wins its second national title. Mountain West Conference (MWC) is organized; BYU leaves the WAC, with its women’s teams having taken first or second place in 85.9 percent of the conference finishes.

2001–02

Cross country wins its third national championship in five years. By the end of the 2001–02 season, BYU has taken first or second in 80 percent of MWC finishes.

2002

Michaelis retires as women’s volleyball coach after leading the team for 40 years; she retains her position as women’s athletic director.