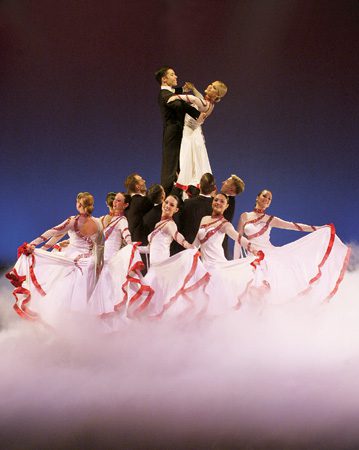

Strains of Andrew Lloyd Webber fill the air and a single bright spot illuminates a woman in a pale-yellow gown, floating above the stage. The spot grows, revealing four men clad in black, holding her aloft.

The men lower her to the floor, where each takes a turn leading her across a stage colored by soft lights. The melodic line of Webber’s “The Music of the Night” reaches a climax, then changes moods, and three more women slip out of the wings. Now four couples move in perfect harmony with the music and each other, their dance accented by rhinestone sparkles cascading down chiffon ruffles.

As the music fades, three of the female dancers disappear behind curtains, leaving the soloist as she began, illuminated by a single spot, floating on a blackened stage. The audience responds, filling the air with thunderous approval. The light goes out and dancers position themselves for the next movement in a symphonic evening with BYU’s Ballroom Dance Company.

Amid the pageantry one summer evening during the team’s recent tour of the British Isles, a woman wept as she watched the students perform and wondered why she couldn’t contain her emotions. After the performance, one of the dancers, an LDS returned missionary, explained it to her while another looked on.

“I listened as my teammate had the wonderful opportunity to identify the Spirit for her and explain who we were and who we represent,” says Roger Wiblin, a senior history major from South Africa.

This woman’s experience is not unique. It has repeated itself again and again as the Ballroom Dance Company has performed before audiences in Europe, Asia, the South Pacific, and North America. The dancers’ undeniable impact stems from a direct charge to represent the university and its sponsoring church as well as from a university ballroom dance program that is like no other. BYU’s ballroom program draws thousands of participants and thousands more spectators, includes on its faculty two couples who have gained world renown in professional dancing circles, and is home to a student touring team that has won 17 U.S. and 14 British formation championships. The program enjoys dedicated leadership and rich support from church, school, and community, all helping to extend the influence of ballroom at BYU from dance classes in the Wilkinson Center to stages around the world.

Seth Redford leads Elisabeth Larson through the sweeping steps of the Ballroom Dance Company’s standard medley. The company used its two medleys – standard and Latin – to win two more British Formation Championships this spring, bringing its total to 14 titles.

Dancing Across the Plains

Dance at BYU is steeped in a tradition older than the university itself. “The Church has a rich history of dance,” observes Lee Wakefield, artistic director for the Ballroom Dance Company and the university’s division administrator over ballroom dance. “The pioneers danced across the plains, the Church held dance festivals for years, and until fairly recently, annual Gold and Green Balls were a highlight in many wards and stakes around the world.”

Such exposure and cultural acceptance translated early on into BYU students eager to learn the two-step, waltz, and Charleston. For years the university offered dance classes that included a taste of several genres, but a specific focus on social dance didn’t exist until 1953 when Alma Heaton joined the faculty as a recreation professor. Heaton came to BYU having taught social dance for a nationally recognized dance studio, and it seemed logical to continue that instruction at the university level. Heaton’s work set the stage for BYU to become a leader in ballroom dance.

“BYU was the first university to introduce dance into its curriculum; the school’s involvement in the sport stretches back for a long time,” observes Brian McDonald, president of the National Dance Council of America, which governs dance competitions in the United States. “And now BYU is, without question, the most influential school in the nation in terms of identifying dance as both a sport and a respected curriculum.”

In fact it was the school’s dance reputation that drew Wakefield to BYU in 1972. First introduced to social dance at 14 after his family moved from Wyoming to California, young Wakefield began competing while in high school. For four years he and his dance partner took weekly lessons from a professional instructor in San Francisco; when he arrived at BYU as a student, he started teaching classes himself.

A semester after Wakefield arrived, Linda Baes came to Utah. A Catholic from Tennessee, Baes chose BYU for one reason: “I wanted to ballroom dance, and there was no other university that had a dance program.”

After six months Baes joined the LDS Church, and the next year she and Wakefield married. The two danced together at BYU for a short time before moving to California, where they pursued a professional dancing career. In a relatively short time, the Wakefields danced their way into the national and international limelight. For six years they trained, coached, competed, and gained experience that would prove invaluable when they returned to BYU in 1980 to head the ballroom dance program. After returning to Provo the pair continued to compete, capturing two consecutive national championships in the theater arts category.

But they traded the sporadic schedule of competing for the stability of teaching so they could add other things to their lives. “Our priorities were different than most of those in our field,” says Lee Wakefield, now a BYU associate professor of dance. “We took time off from competing to have children, and eventually our commitment to our family meant we simply didn’t have the time to compete.” Their commitment to BYU’s program, however, continued, fulfilling their deep desire to remain active in their sport.

In their teaching over the years, the Wakefields have trained many dancers who have gone on to compete professionally. One such couple returned to BYU in 1994 to direct the backup tour company. Curt and Sharon Holman met as members of the Ballroom Dance Company in the mid-1980s and continued dancing after they left BYU. In 1994 they were named the U.S. Rising Star Theater Arts Champions, they have been repeat finalists in the U.S. and British championships, and in 1997 they placed fourth in the British Invitational Championships. Now as members of the ballroom faculty at BYU, they join their mentors in creating and sustaining a championship program.

Wakefield downplays his contribution to BYU’s heightened reputation over the past 18 years: “When we arrived at BYU, a lot of essentials already existed. The university had a long history of support, a lot of classes were being offered, facilities were great, and there was a large enough pool of interested students that we could put together a talented group of performers. Everything was in place, making it possible for the program to blossom.”

Immersed in Dance

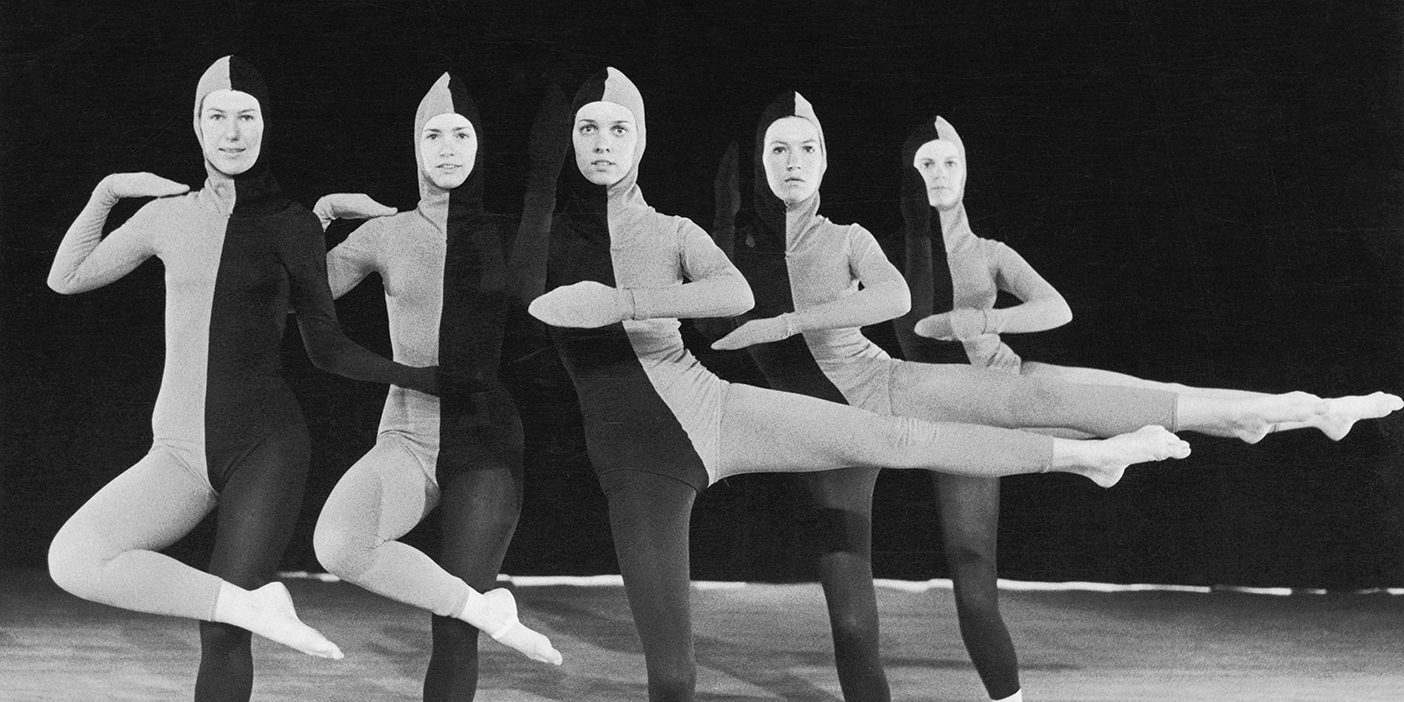

Spinning in the spotlight, Lee and Linda Wakefield demonstrate the talent that took them to the top of the professional dance world. For the past 18 years, the Wakefield have spun their professional success into a world-renowned ballroom program at BYU.

And blossom it has. Every semester approximately 2,500 BYU students fill some 50 sections of social, ballroom, and Latin American dance classes taught by seven full- and part-time faculty members and 30 graduate and undergraduate teaching assistants. Students who want an even deeper immersion audition for 160 slots on three ballroom teams (Wakefield compares them to sophomore, junior varsity, and varsity sports teams) that exhibit their talents at an annual ballroom dance concert. The “varsity” team, or Ballroom Dance Company, also goes on two per forming tours every year. On these tours teams have glided across stages before sell-out audiences in more than 30 countries, including the Philippines, China, and Russia.

In addition to performing, the university’s 36-member touring company competes against teams from around the world. The company has chalked up 17 straight years as United States Formation Dance champions. Divided into two teams corresponding to two divisions of competition, standard and Latin, the company has won at least one division title each time it has attended the British Formation Championships, one of the premier ballroom competitions in the world. The team has accumulated 14 British Formation Championship titles.

Most BYU students who sign up for dance classes, however, don’t have their sights set on international competition; they just want a fun class.

“I looked at people who did ballroom and they looked like they had a lot more fun than people out there just dancing the disco,” says Michael Berglund, a recent graduate of BYU’s MBA and graduate engineering programs. Berglund, from Fallbrook, Calif., took a social dance class and a Latin dance class to break up a heavy engineering schedule and continues to use his dancing skills for fun. “I have a lot of Latin friends, and I love being able to Latin dance with them,” he says.

Other students find they can’t stop with just one or two classes. Paul Freeman, now a senior manufacturing engineering major, initially signed up for social dance simply, he says, “because I had just returned from my mission and wanted to feel more comfortable around girls.” Although he enjoyed his first class, Freeman describes himself as fairly uncoordinated. “I struggled with the steps, and I wasn’t really very good.”

But when a teacher suggested he try out for one of the teams, Freeman decided to give it a shot. “I didn’t have anything to lose,” he says. “Besides, I thought it would be nice to tell my kids someday that I’d at least auditioned.”

When Freeman, who is from Mesa, Ariz., found out he’d made a team, he celebrated with dinner at Taco Bell and promptly signed up for more advanced dance classes. He ended up performing with the Ballroom Dance Company for three years, serving as president in 199798.

Lee Wakefield (right) helps tour team members Todd and Alison Wakefield (only distantly related to Lee) perfect their from in the tango. As they polish style, team members also prepare to share spirit and testimony with audiences worldwide.

A Hotbed for Ballroom

The dance company’s reputation and the strong program at BYU have contributed to avid community support. The evidence of that support is found in packed audiences for BYU performances and in nationally recognized ballroom programs at neighboring Utah Valley State College and area high schools.

Because Utah County is such a hotbed for ballroom, in 1996 BYU began a 10-year stint as host of the U.S. Ballroom Championships. Speaking of the new venue in 1996, American Ballroom Company president John Kimmins said, “The professional couples will especially appreciate the chance to dance before what will easily be the largest audience for any dance competition in the United States.”

Kimmins’ statement proved prophetic; some 6,000 ballroom groupies flocked to the first championship in Provo, easily dwarfing the audience of 1,000 that gathered in Miami the previous year. The 1998 competition drew a crowd of more than 10,000.

“We’ve been able to build ballroom dance in Utah into a spectator sport,” Wakefield observes, an assertion supported by attendance at BYU’s ballroom dance events–some of which have to be held in the Marriott Center to accommodate the crowds.

BYU’s teams also attract attention for their commitment to wholesome performances and modest costumes. “The company’s primary goal is to spread the gospel through dance,” observes Linda Wakefield, co-director and costume director for the team. “We have to be constantly aware of the things that we do-our actions, movements, steps, and motions. We strive to be sensitive and selective in our choreography, costuming, and conduct.”

That sensitivity has made an impact on others in the dance field. “BYU’s program and its team have been so helpful, so influential to the industry as a whole,” says McDonald. “The university’s standards and its ideals motivate others to a higher performance.”

Recently when the National Dance Council considered adopting dress standards for certain dance competitions, it turned to Lee Wakefield for help. Implementing parts of the BYU dress code, he wrote costume guidelines that were eventually implemented. “What we do, what we wear, what we’ve accomplished is respected; we are making a difference,” says Wakefield, who directs the council’s ballroom department, overseeing all aspects of ballroom competition nationwide.

McDonald doesn’t mince words in explaining how much of a difference. “Let me explain it this way: We in America would be at a terrible loss if we did not have the involvement of Brigham Young University and the standards and curriculum they have set for ballroom dance. They’re an example to the whole country.”

Energy and Excitement that Changes Lives

Performers are very aware that they are looked to as examples in costume as well as character. Students in the Ballroom Dance Company take seriously their charge from school officials to represent the university and the Church in their travels. Team members work on more than dance steps as they prepare for tours and concerts. “Before every performance, we have prayer as a team,” says Danielle Davis, a senior majoring in dance who has performed with the company for three years. “We pray that we can have the Spirit and that people in the audience can see and feel something different about us. We pray that we can actually bear our testimonies, not just of our love for dance, but of our love for the Savior.”

Davis knows how powerfully the Spirit can convey those testimonies and move a spectator. A talented ballet dancer, Davis switched to ballroom after she watched the company perform when she was in high school. “I was sitting clear up at the top of the Marriott Center,” she recalls. “But the excitement and energy I felt during the performance was overwhelming.”

Davis’ talent earned her a spot on the tour team her first year at BYU. This year she and her partner, David Wells, a junior family history major from Sandy, Utah, danced their way to the amateur National Cabaret Championship.

“Sitting there in the Marriott Center, I didn’t think I could ever be good enough to be on the team,” she says. “But I decided that day that it was my dream to be a part of something that could make others feel that energy, that excitement. I wanted to be a part of something that changed lives.”

Jason Williams, Divina Teruel, and other members of the Latin team take on the mood of the music as they perform their medley. The tour team has entertained audiences in more than 30 countries around the world.

And now she is. Moving, spiritual experiences-like the one shared with an emotional woman in England this summer-happen often and remind Davis and her teammates that they are part of something special. Team members recall an unusually sunny day this summer spent near Glasgow, Scotland, taking in sights before an evening performance. Their guide was a local bishop from the LDS Church; he brought along Michael, a youth from his ward. The two spent the day with the team, taking them to a bagpipe factory and a local loch before seeing them to that evening’s venue.

The next day the dancers met up with the bishop again. Michael wasn’t with him this time, but the bishop carried a message from the young man-a two-page letter addressed to his newfound friends.

In the letter Michael thanked team members for the way they had accepted him. Earlier that year he had dropped out of school, and he was struggling spiritually. After spending time with these BYU students, Michael decided that he wanted what they had. Consequently, he had decided to return to school and prepare for a mission. His day with them had changed his life.

The life changing goes both ways, and the dancers themselves-whether learning the cha-cha in Dance 180 or performing a routine in an international competition-come away affected by ballroom at BYU.

“I’ve learned so many principles by being involved in the dance program,” says Wiblin, who studied dance in South Africa for several years before attending BYU. “We have to be unified, we have to work well together, we have to be prepared. Those are all eternal principles that benefit me in my life off the dance floor as well, whether as a student or Sunday School teacher or any other role I’m filling.

“For me, dancing is a means to an end, a way for me to learn principles that I can govern the rest of my life by.”

Kellen Recks Adams, a BYU Alumna, is a freelance writer living in Salt Lake City.