Alexander’s Box

A small room in the Harold B. Lee Library offers a glimpse inside the creative world of a Newbery-winning fantasy author.

By Sara D. Smith (BA ’10)

Photography by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

Rachel L. Wadham (BS ’96) has always loved reading, but as a bookish teen she felt out of place in a world that preferred athletes and extroverts—until a children’s author taught her it’s OK to be a bookworm.

When Wadham read Lloyd Alexander’s Vesper Holly series in high school, the books struck a chord. “Vesper Holly is very intellectual, but she also has great, grand adventures,” says Wadham. “For me that was empowering.” Wadham calls Alexander her “rock star” author: his books had no Harry Potter–esque midnight parties, but if they had, “I would have been first in line,” she says.

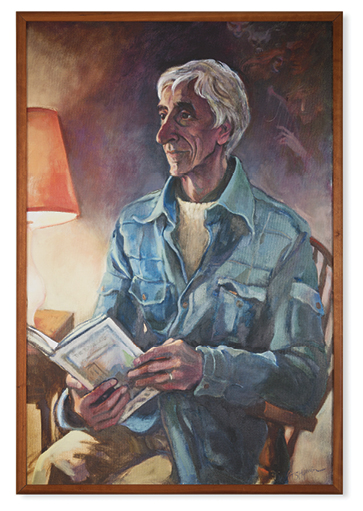

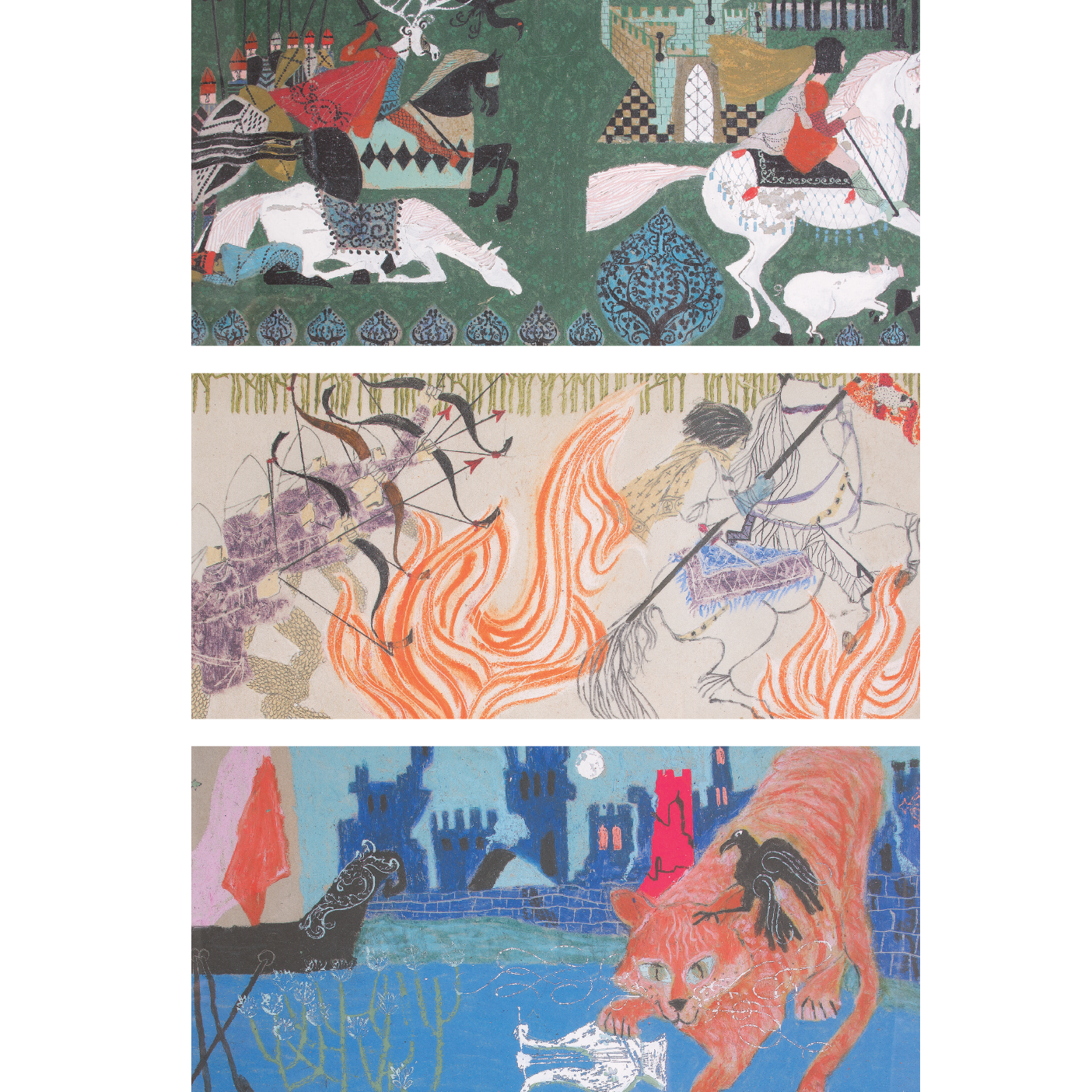

Known best for his Prydain Chronicles that inspired the 1985 Disney film The Black Cauldron, Alexander won dozens of awards, including the 1969 Newbery Medal and two National Book Awards. “Lloyd Alexander was probably the first great [American] contemporary fantasy writer for children,” explains James S. Jacobs, who retired from teaching children’s literature at BYU last year. “He typically wrote high fantasy, which takes place in another world and includes the classic struggle between good and evil.”

“He was a wonderful eccentric. He was a lovable pessimist.” —Michael Tunnell

Today Wadham is the Harold B. Lee Library’s education and juvenile literature librarian, and she couldn’t have designed a better job for herself: she works in an office lined with books, oversees the children’s literature collection, and curates an exhibit of her favorite author’s prized possessions. After Lloyd Alexander’s death in 2007, his manuscripts and the contents of his office were donated to BYU. The exhibit, called Alexander’s Box after the author’s own nickname for his office, re-creates his workspace in the library’s juvenile literature section.

Alexander, who lived most of his life in the same house in Drexel Hill, Penn., has strong connections to BYU. Jacobs knew Alexander personally: after he wrote a dissertation on the author in 1975, they developed a close friendship nurtured by letters, phone calls, and visits. Years later, Jacobs’ student Michael O. Tunnell (EdD ’86), now a BYU professor of children’s literature, also wrote his dissertation on Alexander and befriended the author.

“Dr. Jacobs’ and Dr. Tunnell’s connections to Alexander were very deep, personal friendships, and their scholarly legacy is very much tied to him as well,” says Wadham. “To have professors with that connection and that passion for his work makes BYU a great place to have his things.”

Jacobs’ friendship with the author began with his first visit to Alexander’s home in Drexel Hill as a graduate student. “He opened the door, and he was visibly nervous. I mean, I was nothing—a college kid—and he was a famous author,” remembers Jacobs. “But it didn’t take long for him to become at ease, because he focused on me. I was just a kid who showed up at his house, and he was concerned that I felt welcomed and relaxed. He not only was a great writer, he was a fine human being.”

“He was a wonderful eccentric,” says Tunnell. “He was a lovable pessimist, always quite certain that things were likely to go badly. In fact, one of his friends used to say that Lloyd always saw a hearse in the rearview mirror. Lloyd also was a homebody and hated to travel in his later years—and he valued and protected his privacy without being standoffish. But he loved learning and was as well read as anyone I ever knew.”

As an undergrad, Wadham also got the chance to meet Alexander in person—she took a class about him co-taught by Jacobs and Tunnell that culminated in a visit from Alexander himself. Jacobs says Alexander had promised to visit Provo, but it took years of reminding to get the shy, reclusive author to leave home. At BYU Alexander spoke to a packed de Jong Concert Hall, then spent nearly four hours with Wadham’s class.

“He was one of the most humble people I ever met,” she said. “He had a fun sense of humor. I could tell he loved his fans; he loved to listen to their stories, loved to find out who they were. He didn’t have any kind of ego.”

“The stuff in his office was junk. . . . It was his junk, and he loved it.” —James Jacobs

As Alexander grew older, he began to consider the fate of the eclectic collection of objects decorating his beloved “box.” “He knew that he had people here at BYU who love him,” says Jacobs, who, along with Tunnell, suggested Alexander consider donating his papers and possessions to BYU after his death.

“The stuff in his office was junk,” continues Jacobs. “He did not spend money on it—it’s cheap furniture, cheap everything—but that’s where he lived. It was his junk, and he loved it.” BYU was willing to dedicate the space and resources needed to care for his things, and soon Alexander agreed. “I think we offered him a tiny bit of immortality,” says Jacobs. “He must have liked the idea of not having everything just disappear.”

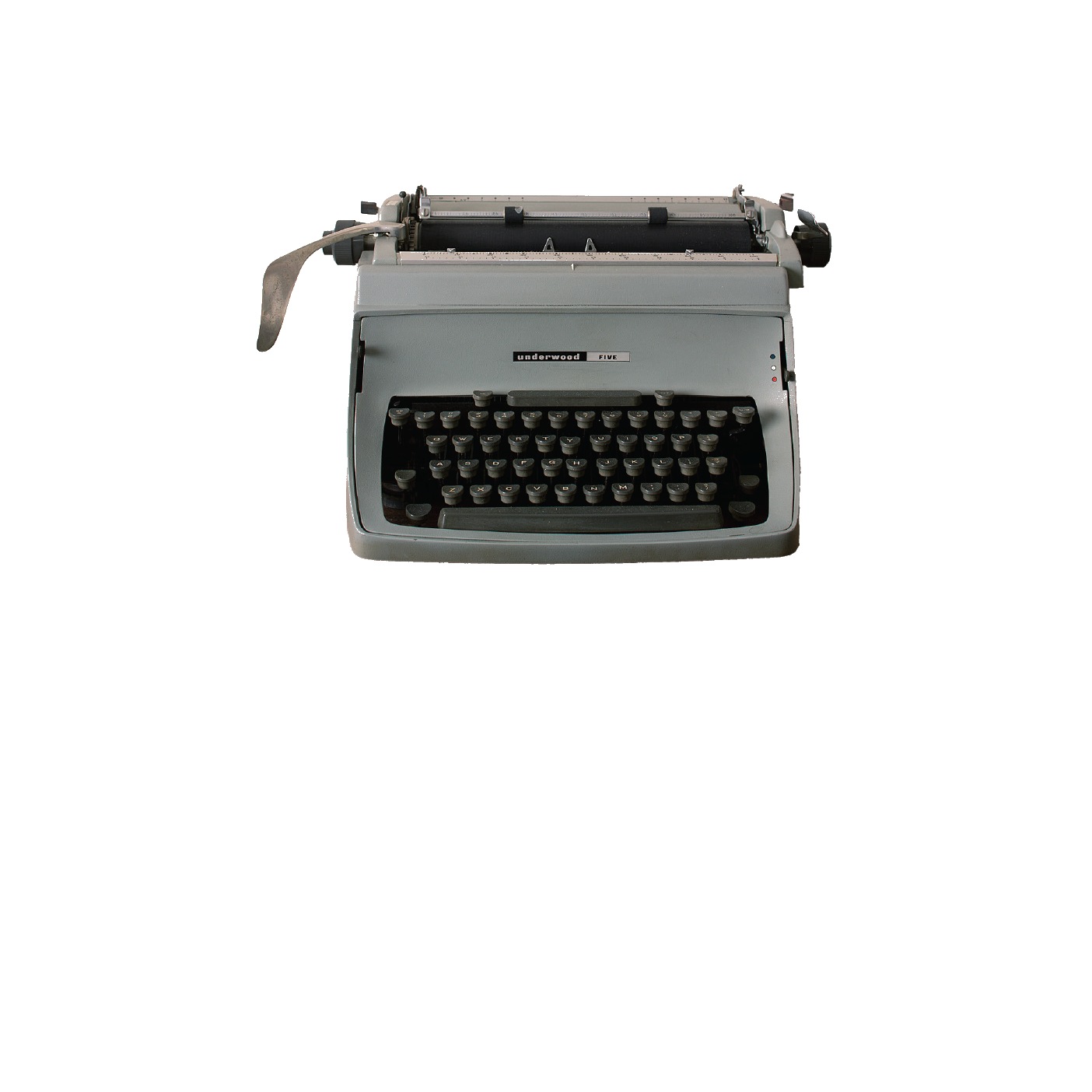

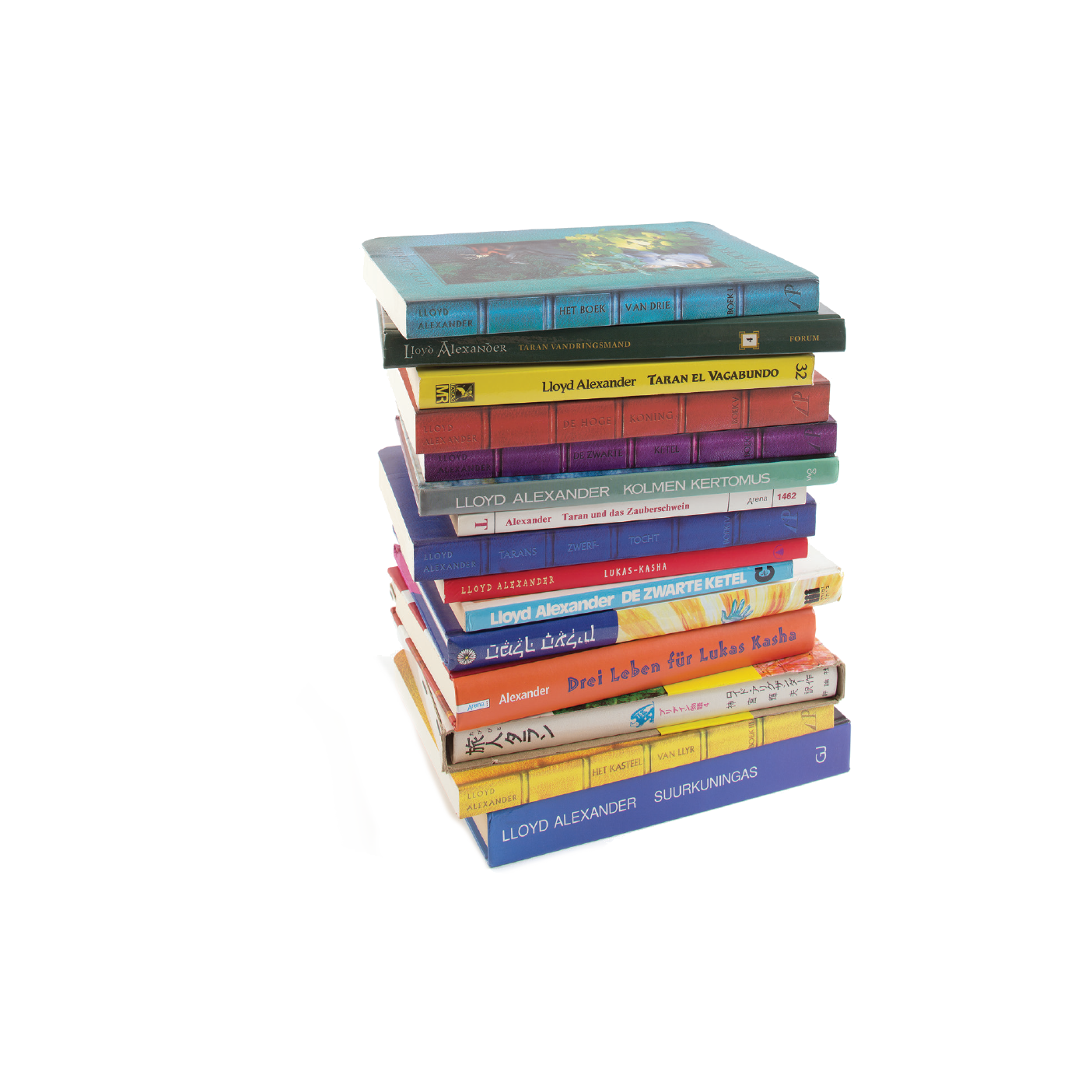

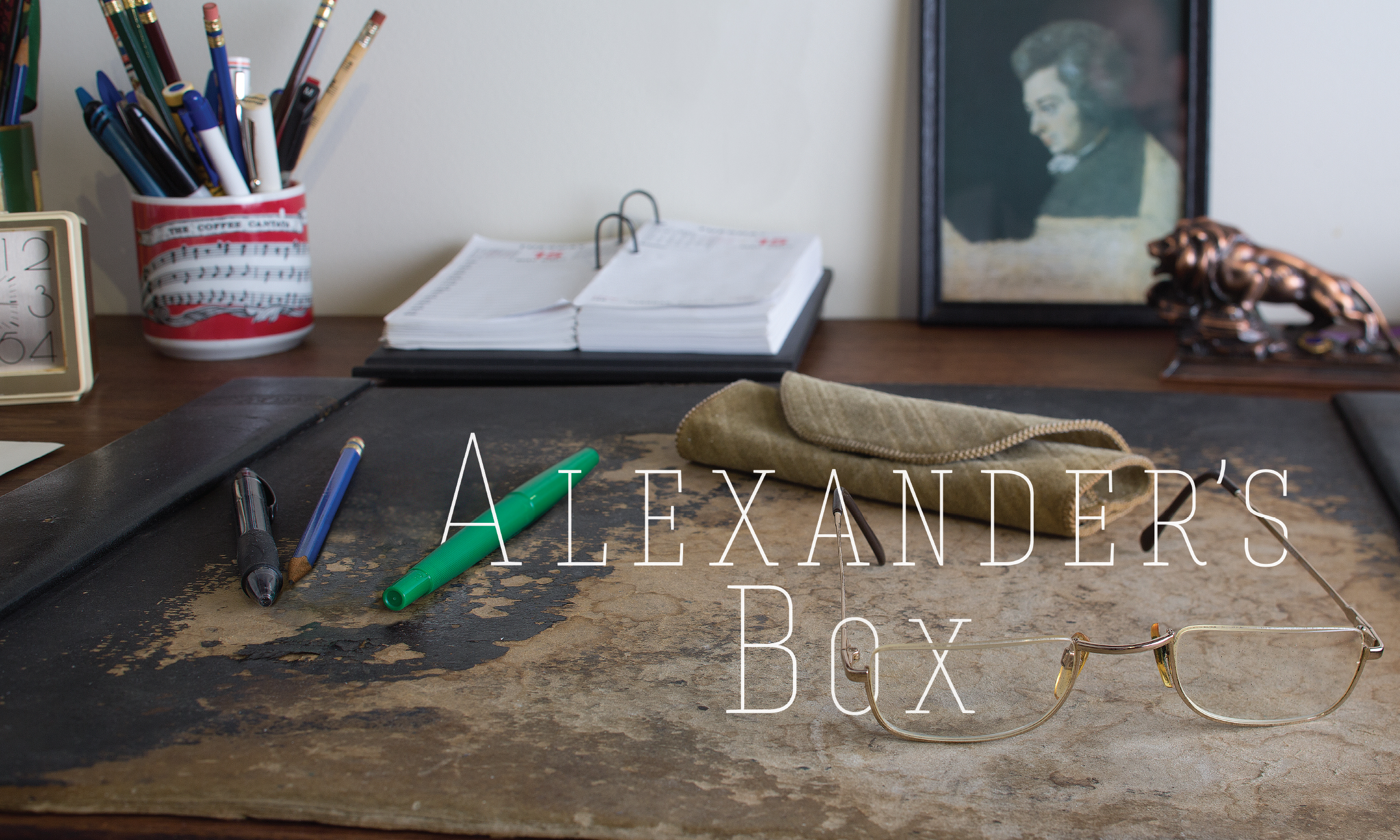

The Alexander’s Box exhibit keeps Alexander’s works and legacy alive for another generation of readers. Located in the library’s juvenile literature collection, the exhibit occupies a small room alive with security sensors. Along one wall, display cases contain his violin, original manuscripts, Newbery Medal, and other memorabilia. Another wall features cover art from his Prydain series and bookcases filled with his many books—in various languages and editions. And in the corner is a nearly exact replica of his workspace—his chair, his 1960s Underwood Touch-Master 5 typewriter, and his desk, spattered with the objects he kept close while he wrote: books from his extensive collection, his daily calendar, a portrait of Mozart, and gifts from fans.

“The essence of the exhibit is to show a writer at work, to show someone who surrounded himself with interesting things that helped devise his creativity,” says Wadham. “I would like people who see it to be empowered to embrace their own creativity, wherever that creativity lies—to realize how important it is to find something that they love and just go for it and engage in it. I think Lloyd Alexander would be greatly honored.”