By Todd A. Britsch, ‘62

In the frontier settlement of Provo some 110 years ago, townspeople, students, and teachers built a school. The product of their efforts / the Brigham Young Academy Building (above) – still stands as a gift from pioneer educators and a monument to BYU’s heritage.

Anyone driving down Provo’s University Avenue cannot help but be impressed with the Academy Building’s almost literal rise from the ashes. But for those of us whose lives were shaped and directed there, the restored Academy Building evokes rich and plentiful memories of a time long past. Although it is now hard to separate the imagined from the real, to us this was a place of dreams, where our aspirations became fixed and where learning almost always seemed natural and inviting. The old buildings located at the square gave us a link both to founding experiences of the past and to the emerging greatness of the university. This link was so strong, in fact, that some of us never could leave the school we learned to love there (thus three of the past four BYU academic vice presidents were B.Y. High graduates). A good number of my classmates at B.Y. High went from kindergarten through their bachelor’s degrees in schools that were part of BYU. I was a relative latecomer, entering the Training School in the fourth grade. Because of the long association so many of us had with the school, the announcement that BYU would close its K–12 operation in the late 1960s came as a shock, and the subsequent sale (in 1975) and crumbling of the buildings wrote a sad epitaph to a location that was once the vibrant center of a unique educational venture. While we were students there, even the rather run-down character of many of the buildings added a surprising patina to all that we experienced, and the light filtering through the tall trees, especially in autumn, created a soft radiance in the place that we never forgot. It was disheartening to see the decaying of a campus to which we had grown so attached. The restoration of this important building guarantees that one key physical reminder will continue to inform future BYU students of the pioneer days of their university.

Because of the long association so many of us had with the school, the announcement that BYU would close its K–12 operation in the late 1960s came as a shock, and the subsequent sale (in 1975) and crumbling of the buildings wrote a sad epitaph to a location that was once the vibrant center of a unique educational venture. While we were students there, even the rather run-down character of many of the buildings added a surprising patina to all that we experienced, and the light filtering through the tall trees, especially in autumn, created a soft radiance in the place that we never forgot. It was disheartening to see the decaying of a campus to which we had grown so attached. The restoration of this important building guarantees that one key physical reminder will continue to inform future BYU students of the pioneer days of their university.

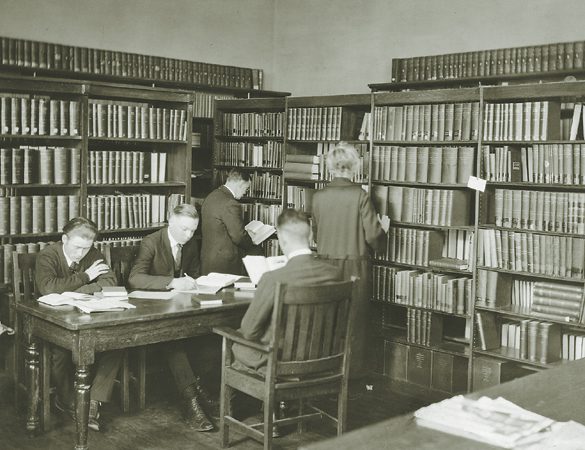

Although most of us have now become accustomed to the name “Academy” or “Academy Square” through the tireless efforts of a diligent few to preserve the historic building on University Avenue (see “Restoring a Dream,” p. 3), this name was unknown to most of us who went to school there during the final years of its use. We called it “lower campus.” During my own earliest experience with BYU, there were nine buildings. The upper campus, located on what many called “Temple Hill,” consisted of the Maeser, Brimhall, Grant, and Joseph Smith Buildings. The library was in the Grant Building, and the Joseph Smith Building was the first of that name.

From its beehive fountain to its archways to its classrooms, lower campus held bounteous treasures of discovery for young minds. Generations of students explored and played in the buildings’ halls before the campus closed in 1975.

On lower campus the five buildings were the Education Building (today’s Academy Building), the Arts Building (where B.Y. High was primarily located), College Hall, and the Training School, which housed the elementary school and the men’s gymnasium. Across the street was the Women’s Gym, larger than the men’s gym and thus the site of theBYU varsity basketball games until they were moved to the more spacious Springville High School gymnasium.

Only gradually did students begin to think of the current campus as the center of their education and activities. But well before the completion of the first Joseph Smith Building in 1941, students had become accustomed to considering upper campus as the main part of their university.

A variety of educational activities took place on lower campus when I first went there in the years following World War II. The high school, originally an important part of Brigham Young Academy, was by then a relatively small laboratory school. Although the junior high was supposedly separate, grades seven through 12 shared facilities, went to assemblies and games together, and were, for most purposes, the same school. There was also a good deal of room sharing with those parts of the university that remained down below–much of the Music Department, some education classes, home economics, and a variety of others. As buildings were added to the upper campus, however, the high school took over more and more of the Education Building, until only College Hall housed any part of the university. College hall was connected directly to the Education Building (it was completed in 1898, only six years after the dedication of its companion), and it is impossible to think of them as separate. These two buildings housed many treasures. Perhaps my earliest memory of this area was of the wonderful glass cabinet that contained exotic fauna collected in Central America by BYA president Benjamin Cluff Jr.’s expedition, which set out in 1900 to discover the city of Zarahemla. Although the large snake was the most exciting creature in the case, we had the most fun trying to locate a tiny bird hidden among the flora. (For a number of years, before our chapel was built, our ward had its meetings in College Hall. I liked to be the one to take my little brother out of sacrament meeting because the display could keep me occupied for a long time.)

College hall was connected directly to the Education Building (it was completed in 1898, only six years after the dedication of its companion), and it is impossible to think of them as separate. These two buildings housed many treasures. Perhaps my earliest memory of this area was of the wonderful glass cabinet that contained exotic fauna collected in Central America by BYA president Benjamin Cluff Jr.’s expedition, which set out in 1900 to discover the city of Zarahemla. Although the large snake was the most exciting creature in the case, we had the most fun trying to locate a tiny bird hidden among the flora. (For a number of years, before our chapel was built, our ward had its meetings in College Hall. I liked to be the one to take my little brother out of sacrament meeting because the display could keep me occupied for a long time.)

Although most performances of university and guest musicians had been moved to the Joseph Smith Building before I started attending concerts at BYU, College Hall was still the site of my first opera (Mozart’s Abduction from the Seraglio, if I remember correctly), and it was the place we held assemblies, performed plays, and formed the B.Y. High community. Its stage remains fixed in my memory as a place of many exciting events. We also loved the College Hall fire escape–a long spiral slide that was attached to the north side of the building. The fire escape was a constant concern to our principal and teachers. It was such a great temptation that several people suggested locking the door to the slide. But locked fire escapes don’t make fire marshals very happy. Instead, a variety of threats were used, with varying degrees of success. Since I, one of the more shy and reserved members of my class, can remember numerous great swirling descents, I expect that the rules against using the fire escape were observed mainly in the breech.

We also loved the College Hall fire escape–a long spiral slide that was attached to the north side of the building. The fire escape was a constant concern to our principal and teachers. It was such a great temptation that several people suggested locking the door to the slide. But locked fire escapes don’t make fire marshals very happy. Instead, a variety of threats were used, with varying degrees of success. Since I, one of the more shy and reserved members of my class, can remember numerous great swirling descents, I expect that the rules against using the fire escape were observed mainly in the breech.

On the top floor of the Education Building was another treasure: a plaster dinosaur skeleton. It was in pretty bad condition and disappeared before I was old enough to have worried about which specific type it was, but it gave us hints that other marvelous things must be hidden in the closed rooms. When I later discovered that most of the adjoining rooms only contained the sewing machines and fabric remnants for the clothing classes, it was a real disappointment.

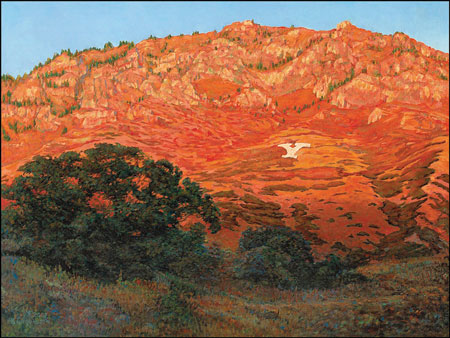

For nearly 50 years the Academy Building was the center of learning at BYU. And even after most campus activities moved to buildings on “Temple Hill,” many classes and learning activities continued on lower campus.

The most special places on lower campus, however, were those hidden completely from view. I never had quite enough courage to explore the heating vents that linked the buildings underground, but my companions described the experience in much the same way 19th-century novelists narrated daring escapes through the sewers of Paris. (I expect that most of these adventures were made of whole cloth, but our explorers made most of us believe that there were great mysteries here.) I did, however, have several labs in the space pushed out under the asphalt from the main science room. These spaces were universally called the “catacombs,” and if we were particularly successful with our concoctions, we could approximate the smells of the catacombs’ Roman namesakes. These labs were small and inadequate by any modern standards, but I’ve recently wondered if Paul D. Boyer, ’39, the BYU-educated Nobel Prize winner in chemistry, might have mixed his chemicals there. It is very likely.

One certain thing is that Philo T. Farnsworth, ’27, used space in the Education Building to undertake some of the early experiments that would later lead him to the invention of television. And when I think of Farnsworth and Boyer, along with a myriad of university presidents, scientists, political leaders, educators, entrepreneurs, musicians, Church leaders, and outstanding parents who received part or all of their training at the lower campus, I’ve wondered what special things were at work in this small, out-of-the-way institution. Somehow, the little college located mostly on the lower campus contributed far more than its expected proportion of outstanding graduates.

One factor that contributed to the success of the small BYU was the surrounding community of Provo. In fact, early BYU and early Provo are hard to separate. In the late 1800s not only was Abraham O. Smoot the mayor of the town, but he was also one of the earliest benefactors of the school. As president of the Utah Stake and of the academy board of trustees, Smoot had primary responsibility for raising funds for the construction of the Academy Building. Although Karl G. Maeser had seen the building in a dream shortly after Brigham Young’s death, the basement lay unfinished for almost seven years. Smoot and others finally were forced to mortgage Church and personal properties to construct the building. Several additional times Smoot had to rescue the academy from threats of closure, and at his death, Abraham O. Smoot’s assets were almost all tied to loans he had taken for the academy. Smoot was not alone in his sacrifice. Many other Provo residents, along with academy faculty members, gave means and muscle to the nurturing of the small–and often struggling–frontier school. Until the first BYU stake was formed in 1956, Provo wards were the students’ wards, and the Provo Tabernacle was not only the religious but also the cultural center of town and university. Students and townspeople alike would stream down University Avenue to hear the remarkable array of world-class musicians (such as Béla Bartók and Sergei Rachmaninoff) who came to BYU–especially during the time of Dean Harold R. Clark, ’18, who directed the Lyceum Series from 1913 to 1966. Few students drove cars, so the sidewalks were jammed as almost the whole student body would attend the events.

Until the first BYU stake was formed in 1956, Provo wards were the students’ wards, and the Provo Tabernacle was not only the religious but also the cultural center of town and university. Students and townspeople alike would stream down University Avenue to hear the remarkable array of world-class musicians (such as Béla Bartók and Sergei Rachmaninoff) who came to BYU–especially during the time of Dean Harold R. Clark, ’18, who directed the Lyceum Series from 1913 to 1966. Few students drove cars, so the sidewalks were jammed as almost the whole student body would attend the events.

And even after the Allen and Amanda Knight Halls were completed, most of the students lived in rooms or basement apartments that surrounded lower campus. Students knew their landlords and often did housework or other jobs for at least a portion of their room and board. Likewise, the citizens of Provo knew the students and the college. It appeared that most of the community was involved in making these students from small intermountain villages into the leaders they became.

I’ve tried to imagine what it meant for a student from rural Utah, Idaho, or Arizona to take a train to a small town like Provo and then walk up University Avenue. Most of our pioneer towns had quite remarkable meeting houses, a small number had stake academies, and there were impressive county buildings in the county seats. But few could claim an impressive educational complex like the lower campus. Students whose parents had instilled a hunger for learning must have felt like they had arrived at an educational banquet.

I suspect that one of the first things a student would have noticed about the academy complex was the old beehive fountain, built in about 1913, for this symbol of industry was a clear link between BYU and its supporting community. Well before the time I was a B.Y. High student, the beehive fountain had ceased flowing, but it seemed still to represent the ties we had with the past. Although we indulged in few philosophical reflections at the beehive (we were most excited when college homecoming queens came there to have their pictures taken), its presence in front of the old buildings was an emblem that transcended generations and tied our school to our culture. That culture placed more emphasis on education than any other culture in the West.

An important thing that we felt on the lower campus, even after the college had largely moved, was the sense that we students had something to contribute to the world. As a faculty child, I was raised to believe in the power of education, of course. But our backgrounds didn’t really matter. No one explicitly told us, but something about learning in these buildings that were the gifts of pioneer educators made us believe that something was expected of us and that we could fill these expectations.

By the time I reached high school, the upper campus was undergoing rapid expansion. The old academy was being left behind, and soon massive building projects changed Temple Hill into today’s world-class campus. A decade or two later, the Training School and B.Y. High became relics of the past, and most of their buildings have now disappeared. But one monument still stands to remind us of our origins and what lower campus meant, not only in our institutional history, but in many of our lives.