BYU’s highly successful capital campaign, “Lighting the Way,” is exceeding goals and fulfilling vision.

IN 1887 it didn’t look like Brigham Young Academy could survive much longer. Three years earlier a fire had destroyed the academy’s only building, and although supporters had quickly begun to build a new, larger structure, a lack of funds halted construction, leaving a crumbling foundation and a vacant lot where weeds grew. Still, classes went on. In rented rooms students learned from teachers who were owed paychecks and who, in turn, owed money to various creditors. The president of the school’s board of trustees took out personal loans to keep the institution running, but at times it seemed like a losing fight.

It was during this time that Karl G. Maeser, the school’s principal, reportedly told his wife and daughter that they were leaving Provo. He was going to teach at the University of Deseret in Salt Lake City, he said. There he could at least expect a regular salary. The family dutifully packed and awaited the word to go north. But the word didn’t come. Two days later Maeser told his questioning daughter, “I have changed my mind. I have had a dream. I have seen Temple Hill filled with buildings–great temples of learning–and I have decided to remain and do my part in contributing to the fulfillment of that dream.”

Brigham Young’s school has always been strong on vision. Brother Brigham clearly stated the purpose–to not even teach the alphabet without the Spirit of God–when he sent Maeser to Provo, and the charge has been restated and rephrased more often than construction crews have invaded campus. But vision on its own is never enough. Vision needs something backing it up–something, as in Maeser’s day, like dedication, sacrifice, and money.

Over the past five years, university supporters have been backing up BYU’s vision through an aggressive capital campaign. “Lighting the Way for the 21st Century” began as a fund-raising effort with a $250 million goal. With still a year left in the original campaign calendar, however, donors have given more than $310 million (see “Exceeding the Goals, Continuing the Giving,” p. 52).

But campaign workers are quick to put this all in perspective. It never has been and it never will be about money,” says Barry Preator, campaign director, with the passion of a teacher explaining an oft-misunderstood concept. On its face Preator’s statement sounds slightly absurd: one of the chief university fund-raisers says this fund-raising effort isn’t about funds.

Did someone put extra bubbles in his Y Sparkle? Apparently not. Preator has said it before, and he’s serious. The story of “Lighting the Way,” he stresses, is not a story about money or donors or ribbon cuttings. It’s not even a story about a capital campaign. “It always has been and it always will be about the lives of Heavenly Father’s children–both those who give and those who receive,” says Preator. In essence “Lighting the Way” is about dedication, sacrifice, and vision. It’s about fulfilling divine potential for a university and for children of God worldwide. It’s about making BYU a brighter light on a hill.

Building the Kingdom

In September 1975 Merrill J. Bateman sat in the Marriott Center for the first fireside of the school year. It was his first fireside back at BYU as the dean of the business school, and he was struggling with his new assignment. Having left BYU four years earlier to join a major international corporation, Bateman had just been promoted to a long-hoped-for position when the call came to return to Provo. He came, but not without misgivings.

Sitting in the Marriott Center, Dean Bateman surveyed the audience, and his eyes fell upon the white-shirted residents of the Missionary Training Center, who were then allowed to attend such firesides. “I saw them sitting there,” he says, “and as I focused on them, the thought came to me, In two, four, six, eight weeks, all of those young people are going to be scattered across the earth. And then another thought hit me: In two, four, six years, everyone else in this audience is going to be going to other parts of the earth. And one of the purposes of this university is to prepare those young people to be builders of the kingdom when they get there. And that was a defining experience for me. It helped me understand the connection of the university to the Church. I knew then why we had returned to Brigham Young University.”

The experience in the Marriott Center provided early shape for the vision Merrill Bateman would bring to BYU as its 11th president: BYU is an integral part of the mission of the LDS Church. In his August 1999 Annual University Conference address, President Bateman articulated the vision that has been taking shape during his administration by outlining four guiding objectives for the university:

1. Educate the minds and spirits of students within a learning environment that increases faith in God and the restored gospel, is intellectually enlarging and character building, and leads to a life of learning and service.

2. Advance truth and knowledge to enhance the education of students, enrich the quality of life, and contribute to a resolution of world problems.

3. Extend the blessings of learning to members of the Church in all parts of the world.

4. Develop friends for the university and the Church.

The first two objectives, he says, are about what happens on campus; the second two deal with BYU’s relationship with the world. “The key focus must be the quality of on-campus education,” he toldBYU faculty, staff, and administrators in their annual meeting. “If our attention is diverted away from the first and second objectives to the third and fourth, the foundation of excellence will be eroded, and the university will fail to reach its potential.”

The elements for reaching these goals are in place, said President Bateman. “There is vision, commitment, and some additional resources, which are the ingredients that will move us forward.”

Providing such additional resources is what the capital campaign has been about.

Online course development is one of the newest ways “Lighting the Way” is helping to educate the minds and spirits of students.

Educating Minds and Spirits

Ever since Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity became standard course material, students have spent hour upon laborious hour seeking to make sense of it all. According to the theory, extreme speeds cause time to slow down and lengths to get shorter relative to a stationary observer. For the average 18-year-old (or even the average 45-year-old) such concepts can be confusing. Particularly perplexing is the problem of perception. Unless they are observed at near the speed of light, the consequences of Einstein’s theory are practically impossible to detect, leaving college students in a state of scientific stupor.

But BYU students this summer had an added tool to help them master the mystery. Physical Science 100, a scientific introduction for the non-scientific student, is one of several BYU courses that are coming online. Now about half-completed, the course’s Web site is full of assignments and quizzes and computer-generated experiments. The online experiments were especially valuable this summer because in a virtual world nearly anything is possible, including observations of near-speed-of-light phenomena.

“A lot of the students said they never would have understood special relativity if they hadn’t had that online resource,” says R. Steven Turley, associate physics professor and the course instructor this summer. “They could go back and look at the simulations again and again until it finally made sense.”

Applying online technology to education is a growing trend, and BYU is no exception. Although there is still debate about the best way to use computers in classrooms, many professors and administrators at BYU see the technology as a way to enhance learning. Online materials can provide additional study aids, permit customized education, help professors better monitor student progress, or even free up classroom space and professor time.

Money donated during the capital campaign is providing much-needed support for such efforts. In early 1999 the first capital campaign grant for an online course was given to Physical Science 100. Next came Statistics 221, Religion 121, and Biology 100. “These are General Education courses that can impact anywhere from four to five thousand BYU students a year,” says Scott L. Howell, director of BYU’s new Center for Instructional Design.

Online course development is one of the newest ways the campaign is helping to educate the minds and spirits of students. But it’s not the only way. In advancing the first of President Bateman’s objectives, donors have contributed more than $55 million for scholarships and grants in the last five years. The original campaign goal for scholarships was just $40.5 million.

The campaign is also helping students by, among other things, soliciting funds for the expansion and renovation of the Harold B. Lee Library and for new faculty positions, which will help reduce class size. In addition, donations are supporting the school’s Freshman Academy, a program designed to improve the freshman experience by placing students in small groups and increasing their access to faculty members.

“Educating the minds and spirits of students is the core of the university,” says President Bateman. “If we’re not doing that, it doesn’t matter what we do.”

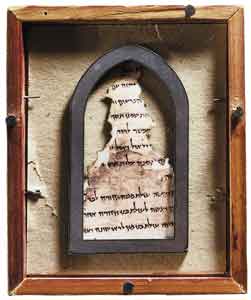

“If we can digitize these fragile manuscripts, ” says Daniel C. Peterson, “then we only have to touch them once and scholars all over the world can access them.”

Advancing Truth and Knowledge

Colonnades rise to meet cornices holding up columns supporting canyon walls. Blackened rock cliffs melt into smooth brown sculptures. A city carved from stone rises suddenly in the Jordanian desert. This is Petra, a place for tourists, archaeologists, Bedouins, poets, and Indiana Jones. It is not, one would think, a place for an electrical engineer.

But there he is, standing in a fifth-century Byzantine church–Gene A. Ware, BYU associate professor in the School of Technology. And he’s not here to go sight-seeing.

In 1993 archaeologists working in the church discovered a pile of about 145 carbonized scrolls buried under nearly four meters of stone. Charred in an ancient fire, the scrolls, with black ink on now-blackened papyrus, were difficult to read and nearly impossible to effectively photograph. But Ware has had experience with such things, and the Jordanian government invited him to take a look. Together with Steven W. Booras, an employee of BYU’s Center for the Preservation of Ancient Religious Texts (CPART), Ware traveled to Jordan, set up a complex array of equipment, and photographed the scrolls. The resulting images not only made the cursive Greek letters easy to read, they preserved the scrolls in digital form so other scholars can read them without handling the fragile papyrus.

The technology Ware and Booras used is called multispectral imaging. Developed in the space program and originally used to photograph the earth, multispectral imaging employs filters to take several pictures of an object–each at a different wavelength of light. Such images can bring out detail and find contrasts that make clear what has been, for centuries, obscure.

And although the technology isn’t new, its application to archaeology is, says Ware. “What we’re doing here at BYU is probably on the forefront of what’s being carried on with applying this technology to archaeological work.”

“Probably on the forefront” is a humble way of saying that BYU pioneered the application and almost no one else is doing it. And that means demand is high for BYU to become involved in discovering and sharing knowledge from such sources throughout the world. When the results of the Petra project were made known, CPART was invited to do the same thing with ancient charred scrolls found at Herculaneum, one of the cities destroyed by the volcano Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

CPART, a department of the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), is funded by volunteer donations made during the capital campaign. In addition to the projects in Petra and Herculaneum, CPART has received many invitations to preserve and make available ancient religious texts–from the Dead Sea scrolls to Syriac Christian documents stored in hard-to-reach Lebanese monasteries.

“People don’t want us touching their manuscripts all the time,” says Daniel C. Peterson, CPART director and BYU associate professor of Asian and Near Eastern Languages. “If we can digitize them, then we only have to touch them once and scholars all over the world can access the manuscripts.”

Such projects help accomplish President Bateman’s second objective for BYU: advance truth and knowledge.

“John Tanner, chair of the English Department, calls this ‘consequential research,'” says President Bateman. “It’s scholarship at the university that helps resolve problems, improves the quality of life on the planet, and enhances the beauty of life. It’s scholarship that makes a difference.”

To encourage such research, in August 1998 the university awarded 11 new professorships made possible by capital campaign contributions. The awards, given to professors across campus, include an extra stipend and research support for five years. Donors have also given more than $7 million for endowed chairs, awards similar to professorships but with greater financial benefits.

Solving world problems through academic research is the goal of the Ezra Taft Benson Agriculture and Food Institute. The institute seeks to develop agricultural solutions to malnutrition and hunger by sponsoring research and education efforts in Mexico, Guatemala, Ecuador, and Bolivia. During the capital campaign the Benson Institute has received more than $5 million. With the donated funds the institute has added programs in Morocco and Ghana and has supported nutrition research and education done by students enrolled in Latin American universities. Without such donated funds, says institute director N. Paul Johnston, the institute couldn’t exist. “We’ve been blessed tremendously,” he says, “and we’ve been able to bless the lives of a lot of people in the developing world.”

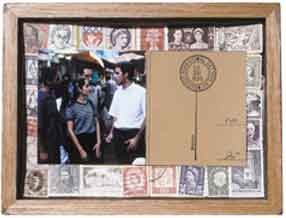

“I’ve always felt a desire to share my educational experience back to Latin America,” says Malcolm Wilson (right), who spent his summer teaching English and computer skills in Mexico.

Extending Blessings

At 5:45 A.M. the streets of Mexico’s third-largest city are bustling. At the side of one of those streets waits Malcolm Miguel Botto Wilson, a BYU senior studying linguistics and anthropology. Ever since Wilson left his native Argentina as a young boy, he has wanted to go back. “I’ve always felt a desire to share my educational experience back to Latin America,” he says. “I’ve been blessed to study, and I think that everyone should have that opportunity.”

This is Wilson’s chance–or at least his first chance–to share his education in Latin America. And so he waits beside a busy Monterrey, Mexico, street at 5:45 A.M. for a bus that will take him to another bus that will take him to the local institute of the LDS Church Educational System (CES). There, at 6:30 A.M., he will begin teaching an English class. Later he’ll teach a class in computer skills and then another English class that ends at 9 P.M. Between classes he’ll work on some studies of his own.

Wilson is part of the first group of BYU students to participate in a pilot program in Monterrey and Sao Paulo, Brazil. Through CES Institutes of Religion, young people in those cities are given an opportunity to learn English, computer, and life skills–if they take a religion class. The BYU students come down for a semester to help out.

“What we’re trying to do here is to teach things that would help the students become self-sufficient,” says Jorge Rojas, director of the Monterrey South Institute. So far the program appears to be working. Students at both institutes have been getting jobs, or better jobs. Cory Bangerter, CES area director for Brazil, reports that students from Sao Paulo’s Brooklin Institute have been hired by airlines, travel agencies, and multinational corporations.

The program has been operating for a year, and in the spring of 1999, a donation made it possible to send five BYU students to each institute. Five students also went to a new summer program in Mexico City, and this fall four students are helping to start programs in three more Latin American countries. Rojas says the BYU student involvement has been invaluable. They teach courses, train teachers, and tutor students. “It’s a win-win situation because the BYU students learn and grow and the people they visit learn from them and grow,” he says. “You develop a brotherhood between peoples of different countries and cultures and languages that is not easily acquired through other means.”

For President Bateman, the Monterrey and Sao Paulo programs are a good step toward meeting his goal to extend the blessings of learning to Church members worldwide. “Even though BYUenrollment stays at a steady state of about 30,000 students, that becomes a smaller and smaller proportion of the age group we’re trying to help,” he says. “So I’ve been looking for ways to leverage the university’s resources to be a blessing to members of the Church anywhere in the world.”

International friendships should come naturally for BYU, says Erlend D. Peterson (let, with Jordanian ambassador Fayez A. Tarawneh and BYU President Merrill J. Bateman). Donations received during the capital campaign are helping to build such relations.

Much of that leverage is coming in the form of increased distance learning options. BYU Independent Study now has more than 100 courses available through the Internet, and donated funds are supporting increased online course development.

Developing Friends

When Erlend D. Peterson hosts a “Friends of BYU” dinner, it isn’t a backyard barbecue before the football game. Most of Peterson’s dinners are in Norway, and the guest lists read like a who’s who of the country–artists, professors, members of parliament, former ambassadors to the United States, the chairman of the Nobel Peace Prize Committee, the chief justice of the supreme court. Many such people come to Peterson’s dinners, and they all love BYU.

As dean of admissions and records at BYU, Peterson has been cultivating relationships with Norway for more than a decade. Through funds donated by a former LDS mission president to Norway, Peterson invites dignitaries to visit Utah and lecture at BYU’s David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies. He has done the same with Denmark, and as the program has grown, an invitation to visit BYU has become a mark of prestige among ranking government officials. Peterson also coordinates donated scholarship funds for Danish and Norwegian students. In both countries BYU ties are strong–so strong, in fact, that in 1997 King Harald of Norway named Peterson a Knight First Class in the Order of St. Olav.

With BYU’s strong international programs and students and faculty who have international experience, says Peterson, such relationships should be expected. “We have a natural resource here that enhances our academic mission and assists the Church in a special way in building relationships.”

Building friendships that benefit BYU and increase recognition for the LDS Church is also among President Bateman’s objectives. And although the president says much of this will be a natural result of other programs, the university is planning to increase efforts like those of Peterson. Through a donation made during the campaign, BYU is developing scholarships and visit- ing lecturer programs with a few key nations. In the future more countries will be added.

Donors have also boosted BYU’s ambassador status by providing more than $4 million during the campaign for performing group travel. Each year hundreds of BYU student singers, dancers, actors, and instrumentalists tour the world, sharing not only their talents but also the message of the LDS Church. In the first eight months of 1999, 16 BYU groups performed before more than 332,000 people in 16 countries. Their televised shows were seen by an estimated 35.5 million people, and the students gave 102 firesides and workshops in music and dance.

Edward L. Blaser, director of the Performing Arts Management Office, says the campaign funds will create an endowment, the interest of which will be a great boon to the program. “It will help us reach further,” he says.

Lighting the Way

During BYU’s first 65 years, the school was repeatedly plagued with the prospect of closure. Money was tight, and on numerous occasions Church leaders and others questioned the wisdom of operating such an expensive venture. But as President Bateman noted in his recent university conference address, “Every time a crisis occurred that threatened the existence of BYU, the heavens were opened and assur-ance was given regarding the future of Brigham Young University.” And the school continued, despite scarce funds.

With nearly 125 years of tradition, BYU now enjoys a well-established role in the Church and in higher education. Among universities BYU is a clear voice, a defender of faithful scholarship. For the Church the university is a builder of saints, an opener of doors, an advocate of truth.

“There are a number of things that an excellent university can do that cannot be accomplished by other Church entities,” says President Bateman. “So we are focusing on enhancing our work on campus–and then we’re taking it to the world.”

“World-class, worldwide” is becoming the slogan of President Bateman’s administration, and BYU is now able to devote donated resources to achieving such goals. With undiminished support from the LDS Church, the university’s basic needs are covered and fund-raising efforts are aimed at enhancing the school’s ability to reach its potential. It was a different scene at the turn of the last century, when mere survival occupied the minds, efforts, and resources of the little academy in Provo. But though today the circumstances are different, the vision is the same.

In 1890 work finally resumed on the Academy Building. Principal Maeser was still there, still teaching, still holding onto his vision. As workers put finishing touches on the structure in the fall of 1891, Maeser prepared to take a new assignment with Church education, and he talked to faculty and students about the future of their school. “There must go through it all,” he said, “like a golden thread, one thing constant: the spirit of the latter-day work. As long as this principle shall be the mainspring of all her labors, whether in teaching the alphabet or the multiplication tables, or unfolding the advanced truths of science and art, the future of Brigham Young Academy will surpass in glory the fondest hopes of her most ardent admirers.”