A Library of Mud and Ashes

A Library of Mud and Ashes

A BYU team images ancient scrolls burned by Mount Vesuvius.

By Julie H. Walker (BA ’93) in the Spring 2001 Issue

Photos by Mark Philbrick (BA ’75)

Nothing in the charred and crumbling appearance of the Herculaneum scrolls suggests that they are extraordinary or miraculous. The mangled, carbonized lumps—buried by Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79 and unearthed nearly 1,700 years later—look, frankly, like something that should be thrown away.

It is not surprising then that the first excavators thought they were pieces of charcoal—not priceless writings from antiquity—and tossed hundreds of these disfigured scrolls on the excavation trash heap. Fortunately, after a worker noticed writing on one of the blackened columns, 2,000 scrolls from this ancient library were saved.

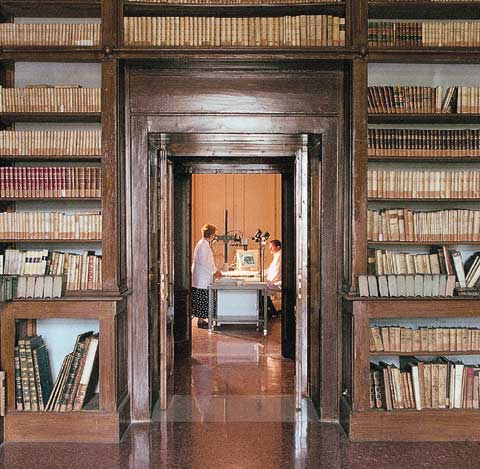

Today, some 250 years later, the recovery effort that began with an excavation continues in a Naples laboratory, where scholars spend their days coaxing uncooperative scraps of burned papyrus out of their 2,000-year-old rolls and peering at the blackened texts through microscopes to catch a glimpse of the ancient world.

In 1999 Brigham Young University researchers were invited to join the project, bringing new text-imaging technologies to aid the research and preservation effort.

“It is probably the worst-case scenario manuscript condition you can imagine: very difficult to read, very difficult to handle,” says Steven W. Booras, ’68, manager of technical operations for the Center for the Preservation of Ancient Religious Texts (CPART), who spent a year working at Naples’ Biblioteca Nazionale where the collection is stored.

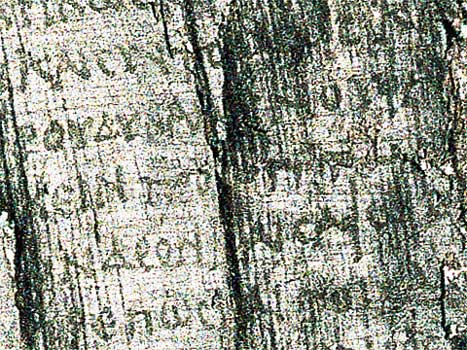

“Many of the manuscripts are so badly damaged, so black, that you cannot see any ink at all,” he says.

CPART—and its sponsoring institution, BYU’s Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS)—became involved in the Herculaneum project at the request of its longtime director Professor Marcello Gigante, formerly of the University of Naples, who was impressed with CPART ’s imaging studies of burned scrolls in Petra, Jordan. For CPART , preserving ancient libraries is an imperative, says Daniel Oswald, executive director of FARMS . Since CPART was established in the mid-1990s, it has worked to preserve ancient texts worldwide, directing projects in Italy, Jerusalem, Jordan, Lebanon, and, most recently, the Vatican library. “These ancient texts are always in jeopardy,” says Oswald.

“All ancient documents are precious,” says Booras. “There is a real sense of urgency to do this.”

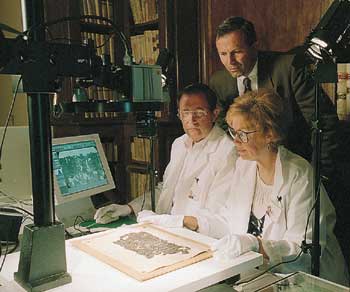

The CPART team is using multispectral imaging to help scholars read some of the most damaged scrolls and to create a digital library of the scroll fragments. With the help of then associate professor of technology Gene A. Ware, ’65, and others, the team has developed techniques for enhancing the readability of deteriorating manuscripts like those at Herculaneum.

Reading Ashes

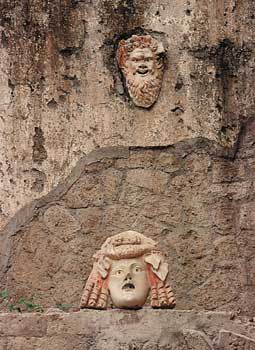

A sister city to Pompeii that was also buried in the volcanic eruption of A.D. 79, Herculaneum was a seaside town that sat between Vesuvius’ fertile foot and the gleaming Bay of Naples. The collection of 2,000 carbonized Greek and Latin scrolls, primarily Epicurean philosophical writings, was found in a luxurious Herculaneum house known as the Villa of the Papyri, which was discovered in 1752.

The scrolls have endured a destructive path through history: first, rain soaked the papyri, then a 570-degree swell of molasses-thick mud engulfed the villa and charred the scrolls. They would remain buried under 65 feet of mud for hundreds of years.

As a result, many of the fragile scroll cylinders are pressed into trapezoidal columns; some are bowed and snaked into half-moons, others folded into v-shapes.

After their discovery the mortality rate for the scrolls continued to climb as would-be conservators struggled to find a way to unroll the fragile manuscripts. Some scrolls were turned to mush when they were painted with mercury; many were sliced down the middle and cut into fragments. Early transcribers would copy the visible outer layer of a scroll, then scrape it off and discard it to read the next layer.

Even today, scholars use metaphors of near impossibility to describe the scroll unrolling process. It is like “flattening out a potato chip” without destroying it, or like “separating (burned) layers of two-ply tissue,” says Jeffrey Fish of Baylor University.

The current unrolling method—developed by a team of Norwegian conservators—involves applying a gelatin-based adhesive to the scroll’s outer surface. As the adhesive dries, the outer shell—which bears the text on its interior—can be slowly peeled off. It can take days to remove a single fragment, months or years to process a complete scroll. Some 300 of the library’s scrolls have yet to be unrolled, and many more scrolls are in various stages of conservation and repair.

On the Herculaneum project, CPART researchers Steve and Susan Booras conducted multispectral imaging (MSI) on 3,100 trays of papyrus fragments and photographed them with a high-quality digital camera. The images will be used to create a digital library that can be accessed by scholars worldwide. Developed for NASA scientists, the imaging technique has only recently been applied to the study of ancient texts. Rather than focusing on light that is seen at wave lengths visible to the eye, MSI uses filters to focus on nonvisible portions of the light spectrum. In the nonvisible infrared spectrum, the black ink on a blackened scroll can be clearly differentiated. In some cases clear, legible writings have been found on fragments that researchers believed were completely blank.

“We’re able to drop out the blackness of the papyri and enhance the ink because they have different reflective characteristics,” says Booras, referring to a scroll that has not been transcribed because it is so difficult to read. “When we use a thousand-nanometer filter, which is in the infrared range, we discover that we have a text that’s perfectly readable as if it were recently written.”

The imaging project has also increased opportunities for scholars. For example, Roger T. Macfarlane, an associate professor of classics at BYU, has been invited to coedit the text from one Latin scroll (known as PHerc 78) with Professor Knut Kleve of the University of Oslo. Macfarlane says the new text is “a really smashing example of what can come out of the Herculaneum papyri.”

PHerc 78 contains the text of an ancient Roman comedy by Caecilius Statius, who wrote popular plays in the early second century B.C. Although several literary fragments survive, the scroll offers the first nearly complete text of any work by this playwright.

“It’s got lots of holes in it, the edges are ragged, it breaks off constantly, but it’s so much more than we’ve ever had before. The imaging technology doesn’t make reading the scrolls a snap because they’re really quite fragmentary still, but it brings us a long way forward,” Macfarlane says.

While the authorship and content of some scrolls is still unknown, most of the Herculaneum library appears to be the works of the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus, a “pivotal figure in the transmission of Greek philosophy to the intelligentsia of Augustan Rome,” according to the Philodemus Text and Translation Project.

Although there is evidence of Christianity in the region around Herculaneum, scholars believe no specific references to Christianity will be found in these early writings. However, according to BYU classics professor John F. Hall, ’75, the scrolls—written between 180 B.C. and A.D. 70—do enrich our understanding of the ancient world around the time of Christ.

“The scrolls demonstrate to us the thinking, the educational directions, and the beliefs of the people of those times. And it’s in the context of those beliefs that Christianity grew and developed,” he says.

Digging Deeper

Because most records from this period deteriorated long ago, the survival of the Herculaneum scrolls is remarkable. Ironically, the forces that burned the scrolls probably ensured their survival by converting unstable organic matter to a more stable carbonized state.

“Would we have these scrolls if Vesuvius had not erupted? Probably not. Papyrus left on the shelf for 2,000 years would probably have long deteriorated,” says Booras. In their current condition, however, there is little hope that the physical remnants of these scrolls will survive. Rapid deterioration underscores the importance of the CPART digital library, which will provide a permanent archive and point of reference for future study.

While the Herculaneum collection is already one of the world’s largest ancient libraries, the collection may grow even larger with continued exploration. Many scholars believe that additional scrolls may be buried in the Villa of the Papyri, which was only partially excavated in 1752. Since the upper-floor library was found in a state of transition—as if someone was moving the scrolls to safety at the time of the eruption—many scholars believe the house’s main library has not yet been found.

“The hope everyone has is that somewhere in one of these charred scrolls is going to be found the writing of an ancient author that has been lost for centuries,” says Hall.

However, the hunt for that ancient library was abruptly suspended last year. Just as modern excavations at the villa brought archaeologists to the doorways of two new lower-level rooms, the Italian government—opting to focus on preservation and restoration of existing sites—banned new excavations. It was a devastating blow to scholars like Gigante, the 50-year patriarch of the Herculaneum scrolls project and a self-proclaimed “son of Vesuvius,” who is anxious to continue the search.

“My faith in this is great,” he says emotionally as he looks over the abandoned excavation. “I hope that before my death I can see all of the villa under the light of our sun.”

While some aspects of the research may be stalled, other areas of study are flourishing. Publications from the scrolls continue to shed light on ancient authors, and the high-tech imaging work by CPART is making it possible to decipher texts that have not been read in nearly 2,000 years. To read from the charred pages of an ancient library, one might say, is to have faith that even the most catastrophic of events do not necessarily signify an end to discovery.