A Heart of Flesh

Raised amid violence and fear, a Palestinian woman discovers that her most threatening enemy is hatred.

By Andrew T. Bay (BA ’91, MA ’94) in the Summer 2018 Issue

Portraits by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94); Illustrated by Anna Godeassi

There’s little remarkable about the scene at a fireside in Medford, Oregon, where two women stand side by side in a chapel and share testimony at the pulpit. But a closer look—and listen—reveals a most unlikely pairing: a Palestinian and an Israeli bearing witness of Christ in Arabic and Hebrew. By the machinations of history and politics, the women ought to be enemies. But Sahar B. Qumsiyeh (MS ’97), a Palestinian woman with a radiant face and deep eyes that have seen much of pain and persecution, counts Israeli former branch member Daphna Glauser as a dear friend.

Their closeness “[gives] me hope that love and friendship are possible between our peoples,” says Qumsiyeh, a BYU–Idaho math professor. “In my journal, I write about it a lot. ‘I’m shocked,’ I say. ‘How is it possible that an Israeli and a Palestinian could love each other that much?’”

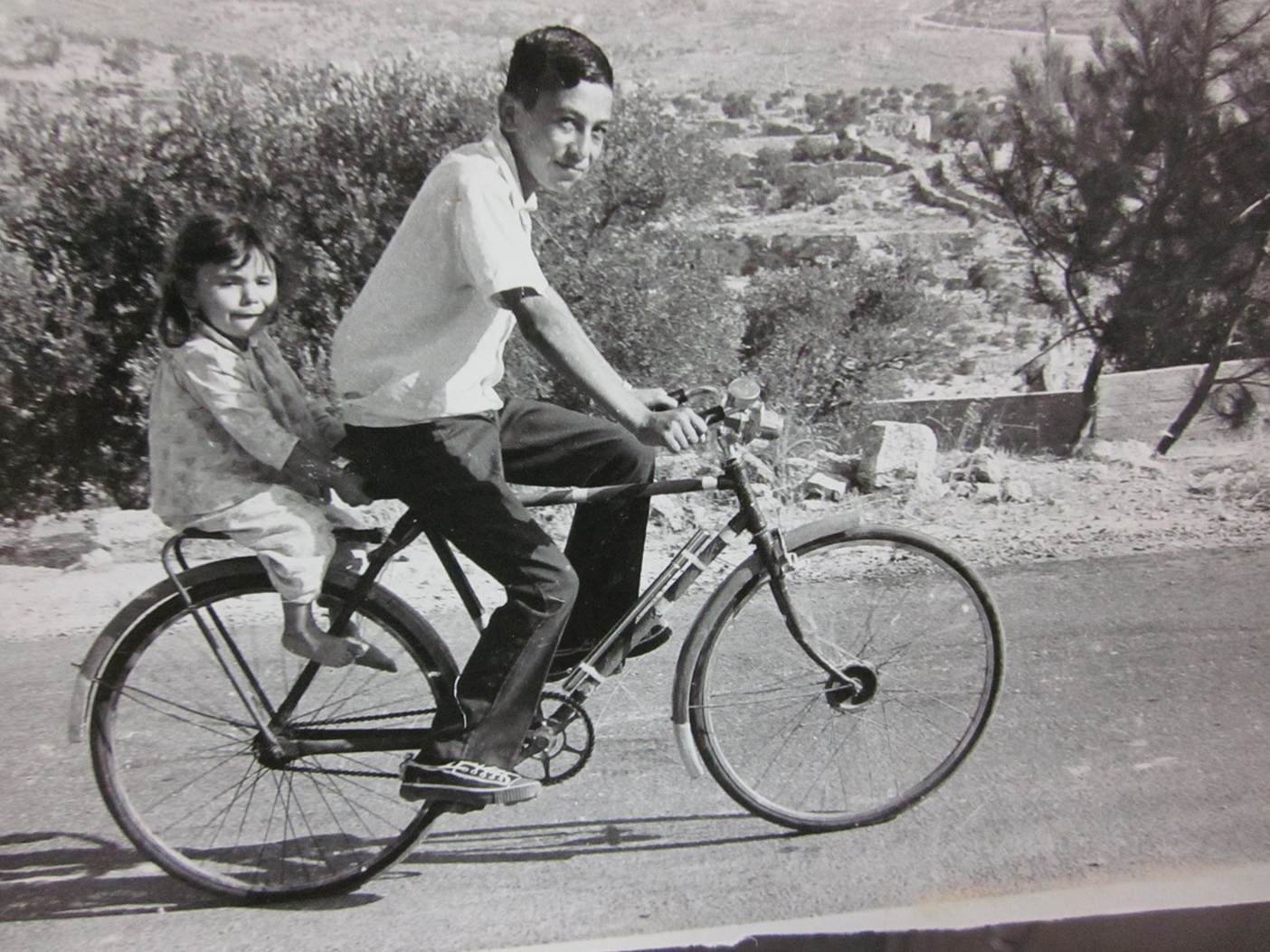

For Qumsiyeh, the journey to find love for would-be enemies was as twisted and fraught as a journey through a security-wall checkpoint. Born in Jerusalem and raised in Beit Sahour, a small Palestinian town nestled in the rolling hills next to Bethlehem, Qumsiyeh grew up in the Greek Orthodox faith and lived among Muslims and other Palestinian Christians. Growing up on the wrong side of history, she was subject to occupation and its traumas, to curfews and soldiers and travel restrictions. But as she discovered a new faith and future, her greatest struggle would be reconciling pervasive feelings of hate and fear. She yearned to find peace in a place where peace was in terribly short supply.

Other Plans

Sahar Qumsiyeh had just one request of God. One night in 1988, she retreated to her room to offer a special prayer. Convinced “that God didn’t love me and hated my people,” the dispirited and depressed 17-year-old prayed with a fervor far more intense than that of the rote “Our Father” prayers her elementary school teacher had taught her. This prayer felt like a breakthrough—she sensed that God would finally listen. All that she asked? “Please. This is enough. I just don’t want to be alive.”

And so, the next morning, “I arose and began bidding farewell to everything around me,” Qumsiyeh writes in her book, Peace for a Palestinian: One Woman’s Story of Faith Amidst War in the Holy Land. “I said goodbye to the flowers, to the trees, and to my family, and to life as I knew it. . . . I felt I would soon die. I was not sad but in fact felt quite relieved and happy.” But the day concluded as her days normally did, and so did the next. Time passed, and Qumsiyeh remained very much alive. God, it seemed, still hadn’t heard her plea.

Beit Sahour, a town of narrow roads, cement and limestone homes, and small gardens with almond, lemon, olive, and fig trees, had not always been a place of sorrow and despair for Qumsiyeh. As a child she spent many happy hours at the home of her grandparents, respected educators in a town dotted with schools. “We’d eat, play games, and laugh,” she remembers. “Sometimes we’d play at the beach.” She often heard her grandparents’ life stories—how they’d lost everything but saved themselves from poverty and ruin through education. A talented student, Sahar wanted to follow in their footsteps.

But as she grew, Qumsiyeh became aware of increasing military control, and fear invaded her life. She drew back from the armed soldiers she had to pass on the way to school. Once, the students in her fifth-grade class heard gunshots and smelled tear gas; a canister rolled into their classroom. Although Sahar recalls her panic and the burning pain, even more vivid in her mind is the image of another little girl, huddled on the floor, shrieking in terror for her mother.

At age 16 Qumsiyeh had entered Bethlehem University to study math, but after a student protest following the killing of one of her classmates, the university was shuttered for two years. Qumsiyeh became anxious and depressed. “We were under curfew a lot,” she recalls. “You couldn’t leave the house. . . . You could be shot. We didn’t have any food, for weeks sometimes. . . . We lived off the eggs of our chickens and food from our garden.” Her brother-in-law was arrested several times. “I would see my sister and her suffering and my nieces and nephews just traumatized,” says Qumsiyeh. “Soldiers would come in the middle of the night and take their dad to jail for no reason and keep him there. . . . He was trying to help the community and organize support for people suffering under curfew.”

And now God would not grant her request to die. God, it seemed, had other plans for Qumsiyeh, plans delivered in the form of a newspaper ad. Once the Palestinian uprising subsided, Qumsiyeh completed her math degree and taught elementary school. She had applied to American University in Washington, DC, for a graduate degree in statistics and even received a $56,000 scholarship. She felt settled about the move—that is, until she saw the

And so she turned again to prayer. “I went to the Church of the Nativity and lit a candle and prayed,” Qumsiyeh recalls. “I just felt strongly about going [to BYU] after that. I knew I should. It was weird for me to stand up and tell my family, ‘I’m going to BYU anyway.’”

But in 1994 she boarded a plane and did just that.

New Faith

Sahar Qumsiyeh knew that Bryce would ask her that day to be baptized, and she knew she’d say yes. It was her second discussion with the missionaries. Right on cue, Bryce L. Harbertson (BS ’97, MBA ’01), a fellow statistics student and friend, blurted out, “Sahar, will you follow Christ and be baptized?” He says the elders shot him a look as if to say, “What are you doing?” But Bryce’s question was one Qumsiyeh could readily answer.

Harbertson, a resident assistant at Deseret Towers, had met Qumsiyeh walking to DT from class. He had assumed that, because she was Palestinian, she was a Muslim, which led to a conversation about her faith. He later gave her an Arabic copy of the Book of Mormon.

At BYU Qumsiyeh had found kind roommates and friends like Bryce who explained the gospel to her. She attended devotionals and general conference. The restored gospel resonated with her, and she drank in the doctrines. “I liked that it’s logical and that there’s a plan,” she says. “I didn’t used to understand why we had trials and why things were hard.” She says learning that God, Jesus, and the Holy Ghost were not the same being was deeply meaningful. Living prophets made sense. She felt the truth of the Book of Mormon and had a powerful witness of it.

Despite this conviction, Qumsiyeh faced stiff resistance when she announced her intention to change religions to her parents. They accused her of being brainwashed and unfeeling. If she joined the Church, her family warned, they’d be pariahs in their small town. How could she put her personal interests above her family’s wellbeing?

And yet the fire in her heart could not be extinguished, and Qumsiyeh accepted baptism and embraced her new faith, all the while worrying what her life would be like when she returned home to Beit Sahour. How could it ever work? Qumsiyeh feared the answer.

Returning home after receiving her degree tested Qumsiyeh’s fledgling faith. Although she had been raised Greek Orthodox, her family did not practice. As a result, they couldn’t fathom what motivated her sudden devotion and prayerfulness, and they pressured her to abandon her membership.

One day her older brother’s mocking became so aggressive that she began to doubt herself and her decision. “I fled to the bathroom and fell on my knees in prayer,” she says. “That night I received a sacred witness, and after that it didn’t matter what they said. I knew God cared enough to answer my prayer, and I knew the teachings of the Church were true.”

In spite of familial struggles, says Qumsiyeh, she began to feel peace again, a peace different from anything she’d felt before. She wrote in her journal: “My country has never experienced peace, but now I feel my heart has enough peace to cover the entire country of Palestine and to cover all the pain and suffering of my people.”

The Price of Membership

Sweating and nauseated, Qumsiyeh sat in the shaking minivan taxi, the driver bouncing the vehicle first across a cultivated field, then through an olive orchard. Beit Sahour was subject to another curfew, and leaving home to attend church in Jerusalem was even riskier than usual. After a long detour, Qumsiyeh found herself on foot, where she stopped at a checkpoint. Soldiers asked those in front of her for papers; Qumsiyeh had none, but, surprisingly, they let her pass through. She caught a bus, which stopped at another checkpoint. Soldiers came onto the bus and forced all without a Jerusalem ID off the bus—all except Qumsiyeh. The men and women forced to leave were separated and the men treated roughly. One more bus ride and a walk up the hill to the Jerusalem Center, and at last Qumsiyeh arrived at church, three hours after leaving home.

For Qumsiyeh, harrowing journeys to church services each week were the price of her membership. “I prayed for help and received it and witnessed miracle after miracle every Sabbath,” she says. And she learned from others navigating the checkpoints in order to access work, medical care, and other services in Jerusalem.

One day, while trying to get to church, Qumsiyeh shared a taxi with an older Muslim woman who also had no entry permit. When they approached the checkpoint, soldiers told them to get out of their taxi. Their driver suggested they cross the street and try the other side of the checkpoint, but that would put them in direct view of eight soldiers. Qumsiyeh feared being arrested, but the old woman looked at her and said, “Let us try.” And then she prayed aloud, “God, please distract the soldiers so we can pass.” Amazingly, the soldiers distracted, no one noticing them cross the street. Thanks to that Muslim woman’s faith and prayer, Qumsiyeh says, “I succeeded in my quest to worship Jesus Christ at my church with my fellow members.”

For 12 years the prodigious hours-long task of getting to church each week fueled Qumsiyeh’s spiritual growth, as did serving in callings, giving talks, and making friends in the branch. “If someone told me, ‘You can go back and erase all that struggle,’ I would say no, because I wouldn’t be the same person,” she says.

However, Qumsiyeh also wearied from the stress and her mother’s protests. And then, after a near arrest on one occasion and nearly being assaulted by men while walking in the hills on another, she determined she could no longer make the journey to Jerusalem. And so she turned again to prayer and regular fasting—for a year. Her prayer was answered with a job as a United Nations data analyst in Jerusalem—a job that came with a pass to cross any checkpoint.

Free to travel, Qumsiyeh now expanded her service, accepting a calling as president of the Relief Society in the Jerusalem Branch and later for the whole district. So it came as a shock when, after several years of meaningful church service, she felt prompted to quit her job and lose the access to Jerusalem that she so prized.

“It took me three months to quit,” Qumsiyeh says. “I asked myself, ‘What am I going to do? How am I going to serve? Where am I going to get money?” It wasn’t until after she resigned that the purpose of the prompting became clear. Qumsiyeh felt impressed to serve a mission, and she soon received a call to work in the England London South Mission office. “The Lord wanted me to prove I’d be willing to be obedient even though I didn’t know the end,” she says.

Against the Wall

One day during her years of piecing together a travel plan to attend church each Sabbath, Qumsiyeh stood in line at a checkpoint, contemplating a young soldier—an immigrant—turning away people who desperately needed entrance into Jerusalem to work or get to the hospital. The irony of an immigrant denying access to a person who was born in Jerusalem, like Qumsiyeh, sat bitter in her heart. Each Sabbath she found herself swallowing anger and frustration—for the scent of tear gas, for a humiliating strip search she had endured, and for a thousand other provocations and indignities she and her people had suffered.

But that day, as she looked at this soldier, she says her mind turned to words from her scripture study from that very morning: “love your enemies.” Qumsiyeh realized that she had to confront a foe more insidious than any armed soldier—the ease of hating those who had hurt her and her people. She saw that hate stood in the way of her spiritual progress just as the security wall blocked her physical path. She knew what the Lord required her to do, but the thought daunted her. How could it be done? It seemed a superhuman task. And, says Qumsiyeh, she found that indeed it was: it required God’s grace.

Qumsiyeh spent a year regularly fasting and praying to be cleansed of hate. “It’s not like a light switch,” she says. “You say, ‘Heavenly Father, help me do this and change my heart, because I can’t do it.’ You have to believe that He can.” She says she needed to learn to see her enemies as people. “You have to separate the person from the act. Some of the soldiers are brainwashed, taught that we’re all bad. Bad treatment is often the fault of someone behind the scenes. But some soldiers are good and want to help you and even break rules to do that. You have to see the human part of people and see them as children of God.”

And then one day she stood at another checkpoint, again hoping to go to church, again facing a soldier telling everyone to go home. But somehow this time was different. Looking into the soldier’s face and eyes, she writes, “my heart filled with love instead of hate. These feelings of love shocked me. . . . I could feel Heavenly Father’s love for that soldier. In my mind, I was able to isolate every bad thing I had seen the soldiers do. I still hated those acts, but my hate for the soldiers themselves was gone.”

Years before, Qumsiyeh had prayed that God would end her life, a childhood petition that had seemed to go unanswered. However, in discovering her faith and love for her enemy, she found that God had in fact ended her old life, giving her a new one in return. She learned that the Lord could “take away the stony heart” and “give [her] an heart of flesh” (Ezek. 36:26).

For Qumsiyeh, being freed from hate means being free to love—from nameless soldiers to fellow Latter-day Saints from a different background, like her Jewish friend Daphna. She says such friendships “really [help] me have hope for the people of the land. . . . As people follow the Savior, they will find He’s the one who can heal hearts. He’s the one who can bring the people of the land together.”

FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.