Werner Hoeger shares an emotional moment with his son Christopher after both completed their best luge runs ever.

By Michael R. Walker, ‘90

After decades of dreaming, a world-class gymnast turns to the luge to fulfill his Olympic dream.

WERNER W. K. Hoeger, ’74, the oldest male athlete in the 2002 Olympic Winter Games, sat quietly in the start house after three of the fastest luge runs of his life, each faster than the one before. He was anticipating his final attempt. His 17-year-old son, also an Olympic luger, looked over and said, “Dad, you’re happy, aren’t you?” Hoeger replied, “Yes, I am, Christopher.”

That day resulted in a 40th place finish for Werner, his best ever in an international competition. Christopher finished 31st in the field of 50, only six seconds behind the medal winners. The rest of the Hoeger family watched near the finish line, surrounded by cheering fans and clanging cow bells. For Werner, this was the culmination of a lifetime of dreaming and four years of training.

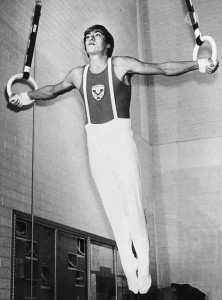

At age 16 Werner left Merida, Venezuela, to join BYU‘s gymnastics program. In his first class, taught by Glenn R. Potter, ’76, the only word Hoeger understood was basketball. His English language and gymnastics skills improved at BYU, but Hoeger’s dream to be an Olympian didn’t materialize in his youth. He was Venezuela’s national gymnastics champion for six consecutive years, but as a team, the Venezuelan gymnastics squad didn’t have the skills to compete at the Olympic level.

For 30 years Hoeger felt that he was denied his Olympic opportunity. But that all changed as Hoeger and his family watched the closing ceremonies of the Nagano Olympics in their home in Boise, Idaho, four years ago.

“I spotted the Venezuelan flag,” Hoeger says. “I got on the Internet and found out that Venezuela’s first Winter Olympian was Iginia Boccalandro, a luger who lived in Salt Lake City. Iginia’s twin sister, Maria, had competed at the same gymnastics national championship as I had in 1975 in Venezuela. When Iginia didn’t remember me, Maria said to her, ‘Are you crazy? You don’t remember Werner Hoeger? He was our idol. Get that man on a sled.'”

The Hoeger family was invited to a street luge clinic, where four Hoegers maneuvered around cones to capture the top four spots in a practice race. Werner and Christopher were invited to train in Park City, Utah, this time on ice. Hoeger’s Olympic dream had made it through another curve and would finish at the 2002 Games.

The luge is not as physically demanding as gymnastics, says Hoeger, but it takes “a lot of courage and kinesthetic sense to feel the G-forces and steer the sled through the curves.” He knows what he is talking about. Hoeger is a physical education professor, director of the human performance laboratory at Boise State University, and author of six fitness texts. Several times he has made contact with the frozen wall of a luge track at 80 mph, resulting in a concussion, a bruised calf, and a broken ankle.

Having reached his goal in Salt Lake City, Hoeger plans to compete in World Cup events until he is 50 and then evaluate whether to compete in the 2006 Olympics in Torino, Italy. In the meantime, he plans to share his Olympic experiences. “There have been some exceptional spiritual experiences in this sport for me. I’m very satisfied with what happened here at the Olympics. One of the results is I can take these stories back and hopefully edify the youth.”