With a little planning parents can find ways to harmonize their work and family responsibilities. One way is to bring children along, when possible, as they work or run errands.

By E. Jeffrey Hill, ’77

Our family loves music. The other day I returned home from a hectic day at work and wanted some peace. I opened the door and was overwhelmed by the cacophony coming from my home. Abby boisterously fiddled away in the laundry room. Aaron blared out jazz on the trumpet from his bedroom. Hannah enthusiastically bowed her way through a beginning cello book in the living room. And dear Emily turned up the volume on our electric piano as she raced through a hymn. The dissonance was earsplitting.

A few days later I had a different experience. The children joined several others in our living room to sing and play Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus.” This time Abby’s violin was sweet and beautiful. I enjoyed Hannah’s tenor line on the cello. Instead of playing the piano, Emily sang alto. And as Aaron’s trumpet punctuated “King of kings” and “Lord of lords,” I could not hold back the tears as I attempted to sing, “And He shall reign forever and ever.”

The two experiences were opposites. In the first the competing sounds were impossible to enjoy; in the second the sounds worked together, creating a unity greater than the sum of the individual parts.

So it is with work and family. For many years “balance” has been the predominant work-family metaphor. We grapple with whether to work late on an important project or leave early to attend a daughter’s softball game. We agonize about whether to postpone a family vacation because a business deal is looming. With a balance metaphor work is the irreconcilable nemesis of family life.

Stewart Friedman has come up with a fresh way of thinking about this. In an intriguing Harvard Business Review article, he and two colleagues maintain that work and family life can actually be complementary, not competing, priorities. Success at work often contributes to success in one’s family and vice versa.1 Perhaps a metaphor of harmony would more richly capture what individuals do to manage the demands of their work and families effectively.

Using the harmony metaphor, work and family questions are not necessarily “How can I limit my work time so that I can balance my family life?” or “How can I get out of the house more so I can have more time at work?” Other, more helpful questions come to mind, like “What am I learning at work that can help me have a better family?” or “How can we overlap work and family time in harmony?” Let me share six practical thoughts about harmonizing work and family life.

Create Energy

Recent research indicates that the depletion of energy as much as the time spent at work explains the dissonance between work and family.2 When you feel like your job is sapping your energy, you have little vigor left for your family.

One way to increase your energy without cutting hours is to make a list of the things you do at work that either drain or energize you. See if you can arrange to do the energizing things right before you go home. For example, if clearing your e-mail box or getting the next workday organized helps you to feel in control and ready to begin next time without delays, that may be the thing that energizes you and allows you to go home without worrying about work.

You might also use commuting time for renewing activities. Try listening to scriptures on tape, music, or inspirational books instead of the radio.

Seize Quality Time

All time is not created equal. Many involved parents strive to increase the quality of the time they spend with their children. One father found that his kids were most willing to interact when they walked in the door after school. Early afternoon was also low-energy time for him at work. He found that if he went home early a couple afternoons a week, he could miss rush hour, take a half-hour break with his children, and then finish up his workday at home.

Bedtime can also be high-quality time. Few kids really want to go to sleep, so they will let their parents read to them, tell them stories, or sing them songs.

Use Shadow Time

In time-use research there is a concept called “shadow time.”3 Using shadow time essentially means doing two things at once. There are many opportunities for work and family activities to overlap without dissonance. For example, I recently brought my 12-year-old daughter, Hannah, to my office for the morning. While I engaged in my primary activity of writing a boring scholarly article, she enthusiastically organized all the books in my office library. At noon I took her out to lunch. I got a full morning’s work done and made a memory with my daughter at the same time.

The same concept applies to running errands at home. When you need to go to the store, take a child along with you. While you perform your primary activities of traveling and shopping, shadow time can help you connect with a child. In our home we have modified a famous credit-card slogan to say, “Never leave home without them.”

Focus

Notwithstanding shadow time, there are times when it is better to set firm boundaries between work and family life. In my experience keeping the Sabbath day holy, for instance, is a key to focused harmony.

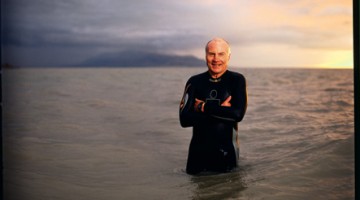

Family vacation may be another time for muting work completely. In today’s world of wireless devices, it is easy to let work bring dissonance to the delicate tunes of vacation renewal. A few years ago I took my wife and three of our children to enjoy Hawaii for an eight-day vacation. I brought my laptop with the thought that I could log on a few minutes each day and keep up with my e-mail. However, the few minutes turned into a few hours each day. Even when playing with the kids in the surf I would be thinking about a work project. On the second day of vacation, my boss firmly demanded (via e-mail) that I join an important 9:00 a.m. conference call the next morning. After replying that I would attend, I realized that the 9:00 a.m. call in New York would be 3:00 a.m. Kona time. Sitting in on that tense conference call in the wee hours of the morning, I reached my limit. I asked myself, What am I doing? I’m supposed to be on vacation! So after the call I locked up the laptop, put away the calling card, and crawled back into bed. I made a resolution that from then on I would throw off my “electronic leash” whenever I went on vacation.

Time spent in such family devotional activities as family home evening, scripture study, and prayer should also remain distinct from work.

Be Flexible

Recent research indicates that those with flexibility and control in when and where they do their work are much better able to find harmony between their work and family life.4 Given the same number of work hours, these flexible workers report both higher productivity and greater harmony in their family lives.

Sharing my own experience with telecommuting might be instructive. For 13 years I struggled to juggle a demanding career at IBM with the needs of my family. In 1990 I started working from home. The difference in my life was immediate. Instantly I gained an hour a day because I did not have to drive to and from work. I could get the kids up for family devotional and breakfast. Because I was working from home, I could listen for baby Amanda while my wife, Juanita, was out. When Abigail had the lead in the fourth-grade play, I could be there on the front row at 11:00 a.m. When work got frustrating I could put Emily in the jogging stroller and go for an invigorating run. The dissonance would dissipate, and I could return to work refreshed. I usually took about 30 minutes off work mid-afternoon to visit with the kids when they came home from school. Jeffrey and I would often play a 10-minute game of one-on-one basketball.

I found myself more focused, energized, and productive at my work. Without the interruptions of coworkers, I could deliver higher-quality products in less time. Soon four of my colleagues were working from home with similar results. Within four years more than 25,000 IBM employees were working in what became known as the “virtual office.”

Simplify

Voluntary simplicity—deliberately choosing to accumulate fewer possessions and engage in fewer activities—is a key to finding harmony in a busy life.5 We live in a materialistic society where we acquire many gadgets and toys. These things have a high cost in time as well as money. When we have too much, we run the risk of obscuring the simple but powerful life melody we hope to compose. One easy way to moderate materialism is to stay out of debt. Buy less, do less, and do fewer things at the same time.

If we use harmony instead of balance for our metaphor, it may be more possible to compose a magnificent symphony of life where we find peace and want to shout, “Hallelujah!” Instead of “struggling at juggling,” we can seek for harmony as we provide for and nurture our families.

notes

1. S. D. Friedman, P. Christensen, and J. DeGroot, “Work and Life: The End of the Zero-Sum Game,” Harvard Business Review, vol. 76, no. 6 (1998), 119–29.

2. D. S. Carlson, M. E. Kacmar, and L. P. Stepina, “An Examination of Two Aspects of Work/Family Conflict: Time and Identity,” Women in Management Review, vol. 10 (1995), 17–25.

3. J. P. Robinson and G. Godbey, Time for Life: The Surprising Ways Americans Use Their Time (University Park, Penn.: Pennsylvania State UP, 1999).

4. E. J. Hill, B. C. Miller, S. P. Weiner, and J. Colihan, “Influences of the Virtual Office on Aspects of Work and Work/Life Balance,” Personnel Psychology, vol. 51 (1998), 667–83.

5. B. Brophy, “Stressless—and Simple—in Seattle: It’s at the Epicenter of ‘Voluntary Simplicity,'” U.S. News and World Report (online). Available at www.usnews.com/usnews/issue/simple.htm.

E. Jeffrey Hill is an associate professor of marriage, family, and human development.

With a little planning parents can find ways to harmonize their work and family responsibilities. One way is to bring children along, when possible, as they work or run errands.