Living Left of Reality

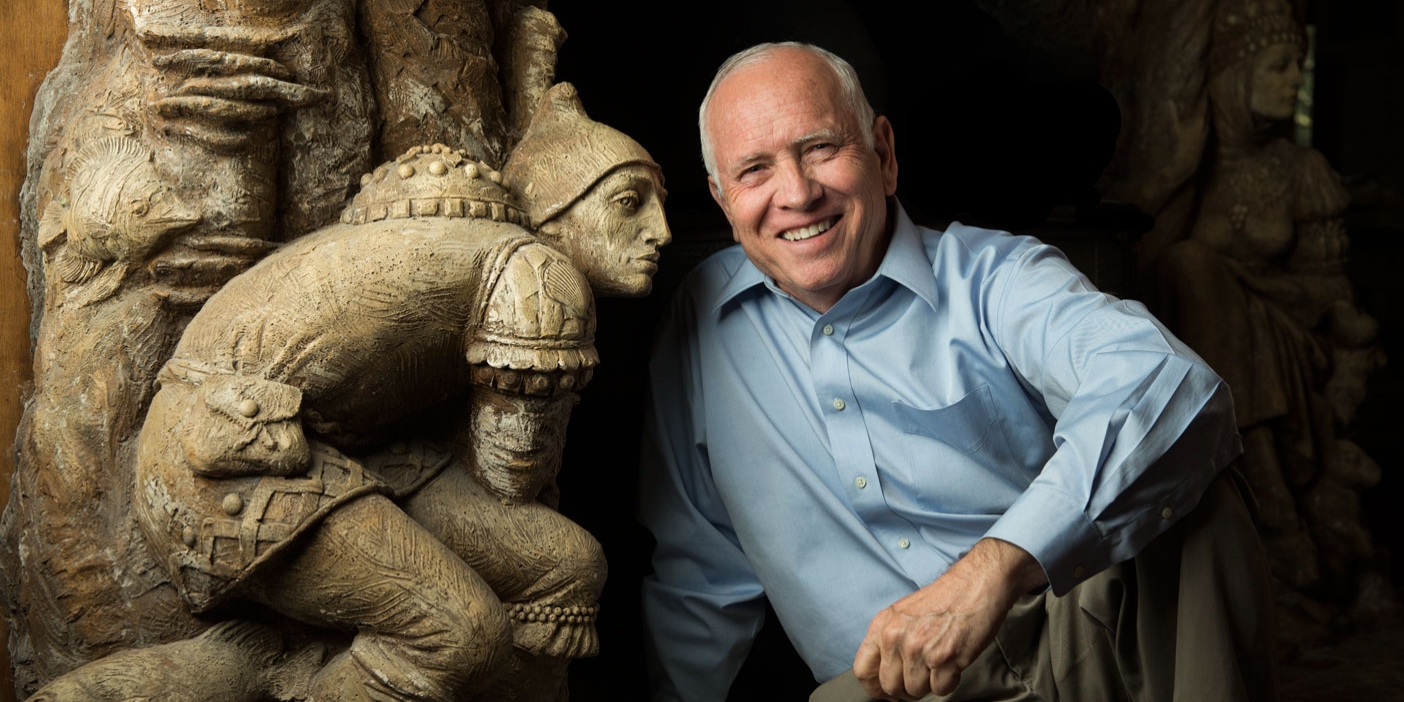

Alum, professor, and fantasy artist James Christensen shares the joy and adventure of living in a world where, as the creator, anything is possible.

By Charlene Renberg Winters in the Fall 1996 Issue

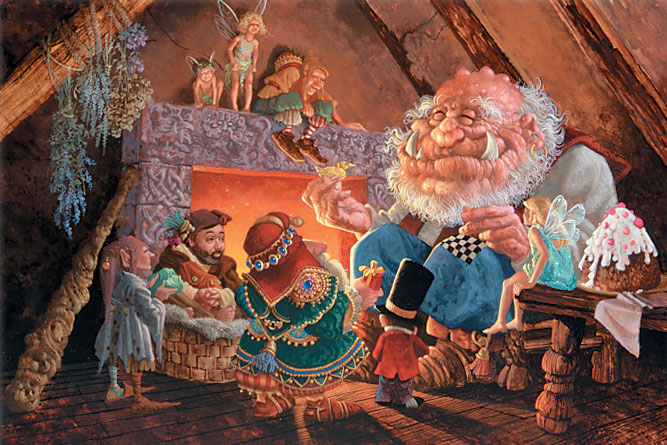

Artwork by James C. Christensen

If fantasy artist James C. Christensen fills his days riding a ship through the sky, roaming the forest with impish fairies, and engaging in an animated chat with the pet fish that floats beside him, don’t be too surprised. This Brigham Young University professor lives in a land just a little left of reality.

He creates a domain where it is not considered unusual for a percussionist to play sea shells and other fishy instruments, for a trio of elegant angels to glide through the evening on a boat across the moon, or a set of dowager ogresses–complete with bright red toenails–to enjoy a spot of tea with their pet mouse.

Yet Christensen’s journey is not isolated. His whimsical artistic style appeals to an extensive and expanding national audience that regularly accompanies him on his fanciful treks.

It is clear his art appeals to many. His limited-edition fine arts prints, produced and marketed by the prestigious Greenwich Workshop in Connecticut, routinely sell out shortly after they are printed. Christensen also has an eager audience for original paintings, bronzes, books, and porcelains of some of his favorite characters. A Utah-based computer software company is even using Christensen’s art to design screen savers.

Regardless of the medium, Christensen’s attraction seems to center on how he changes the rules of reality to create delightfully inventive worlds.

“I’m always pleased when my work jump starts someone’s imagination,” Christensen explains. “I hope my art is more than something I do and then say, ‘Look what I’m giving you.’ I want people to create their own meanings and find their own stories. For me, the art process is not complete unless it becomes thought provoking for the viewer.”

As a teacher, he often suggests that his students create a “hook” that captures attention, something he tries in each art piece. In a recent help session with one of his BYU students, for example, he discussed a portrait.

“This woman is lovely,” he said of the subject, “but you can make her more interesting if you provide something that lights someone’s imagination. What if you put a letter in her hand? With her expression, it could mean many things. Is it a letter from a lover? Has she received bad news? What’s going on here? Or, what if you put a wine glass in her hand? Maybe it’s a poison potion. I always try to give my audience points of access.”

“I’m always pleased when my work jump starts someone’s imagination” —James Christensen

One way he provides such an entry into his paintings is with symbols that add layers of meaning to the canvas. Although the artist will discuss them, he is somewhat reluctant to elaborate on symbols because he wants individuals to contribute their own meanings.

“Several hundred years ago, most people, regardless of wealth or station, were illiterate,” he explains. “Symbols became necessary to help people understand and ‘read’ a painting. We don’t understand many of them today, yet a few–a skull representing death, for instance–are universal and have transcended time and culture. I use some traditional symbolism in my paintings, but over time, I have created symbols of my own that remain consistent from painting to painting.”

One of his most common, the flying fish, embodies magic. “If you and I are sitting here having a conversation and a fish floats between us, that changes everything,” he says. “Immediately you sense that something is not quite right. I use fish as passages to higher levels of understanding and insight. They are intriguing and beautiful, but for me, they are also magical.”

Another frequent symbol is the hunchback. “He is a sort of everyman,” Christensen says. “We all carry burdens and flaws through life; the hunchback is a physical symbol of the ordeals we all face. However, another dimension is at play here. The hunchback reminds us that while we all have weaknesses, it can be through those flaws that the Spirit touches and teaches.”

Many of Christensen’s paintings depict boats, sometimes in water, other times in the air–and, frequently, perched atop people’s heads. One of his celebrated oils, “The Burden of the Responsible Man,” features an exhausted-looking man wearing a boat filled with people. A biographical piece, Christensen painted it when he was feeling overworked and spread too thin. His character holds a porcupine briefcase, he dangles an armful of keys, and he follows a carrot swinging from a fishing pole in the vessel.

“The idea was that I had to keep going, keep moving, which is what all responsible people do. When I painted a woman with all her tasks surrounding her, my wife, Carole, would not let me use the word burden, because to her the tasks aren’t burdens. It’s good to get her perspective; I really rely on her to be an outside voice.”

Christensen often uses his boats to symbolize the voyage through life. “I use voyages extensively. We don’t always know the destination or where the boat is going, but the anticipation and mystery make life enjoyable. A boat may also symbolize the people we travel with at times along our journeys,” he says.

Additionally, Christensen uses clothing as metaphors. “I love historical costumes with all their gold threads, jewels, buttons, and glitz. People use layers of clothing to get away from the core of who they really are. I like to say that the more bureaucratic or aristocratic we become, the more stuff we have. That stuff we wear on the outside is our vanity.”

He says he is especially pleased, however, when someone explains how a particular Christensen work engaged his or her imagination.

“One man told me one of my prints had hung on his wall for a year. He said a picture light next to the print was the last thing he turned off at night. During that year, he had named the characters, invented stories about them, and created his own meanings.

“The painting assumed a life of its own.” —James Christensen

“When he asked me, ‘Is that all right?’ I was delighted. This building contractor had been creative and taken an active role in the painting. That’s what I like. Everyone has an imagination and many experiences he or she can bring to the art.”

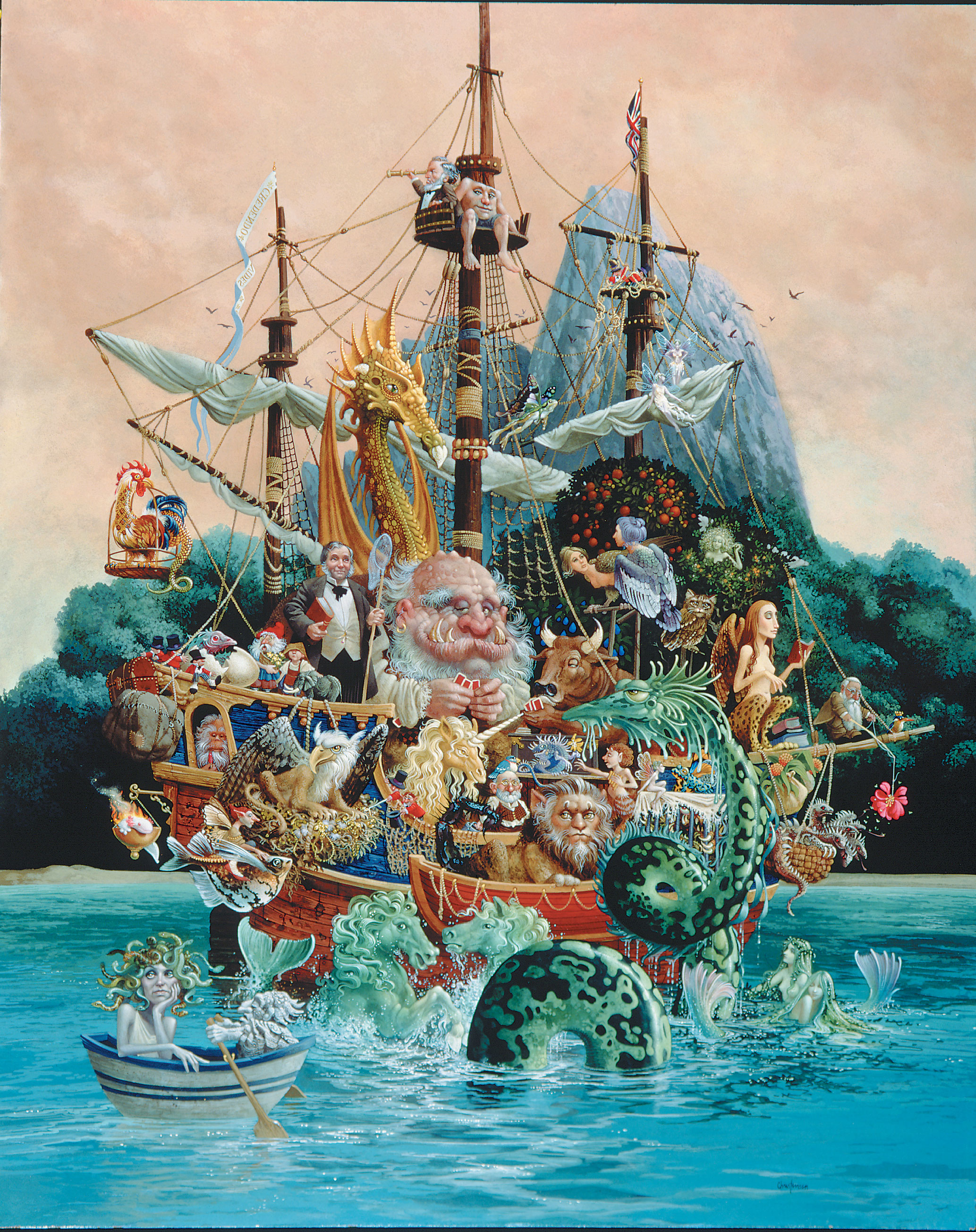

The artist’s most recent project is an illustrated story book with more than 80 paintings and numerous ink drawings. Characteristic of his interest in journeys, the book is called Voyage of the Basset. Clearly his most ambitious creation to date, Voyage required a two-year sabbatical from BYU and nearly a decade of simmering.

The seeds of the endeavor began when he saw a documentary about Charles Darwin’s expedition on the H.M.S. Beagle several years ago and speculated what Darwin would have discovered had he gone in another direction.

“As I watched the show, I wondered how different the journey might have been if Darwin had relied on magic and imagination instead of science,” Christensen says. “Darwin discovered his theory of evolution and sailed into history. I decided to take the journey of imagination and see where I would sail.”

The first result was a painting, also called Voyage of the Basset, featuring mythical creatures aboard a mysteriously magic vessel full of surprises. The ship’s motto, Credendo vides, Latin for “By believing, one sees,” is Christensen’s personal creed as well as that of the painting’s captain. (Credendo vides is carved onto an ornately decorated fireplace at the artist’s English cottage.)

As he painted, the artist conjured scenarios for his characters.

“It is not in my nature to do mere mug shots, so the painting assumed a life of its own,” he says. “My subjects became grouped in scenes that suggested stories. I had a minotaur playing cards with an ogre, which became a little society. I put a sphinx aboard because, after Oedipus solved a riddle at Delphi, the sphinx obviously needed a new one. Medusa looked bored in the petite boat apart from the ship. Neither she nor I had any idea she would become a major character when the painting later became a book.”

He described his originalVoyage of the Basset impressions in a booklet that accompanied the limited edition prints. The stories, however, continued to percolate in his mind even after he moved on to other projects. About four years ago, with Greenwich’s encouragement, he decided to commit himself to turning Voyage of the Basset into an illustrated story book, which was released in September through the press division of the Greenwich Workshop. (Voyage of the Basset has been chosen as a national Book of the Month Club selection, and Good Housekeeping named it among its top 10 gift books.)

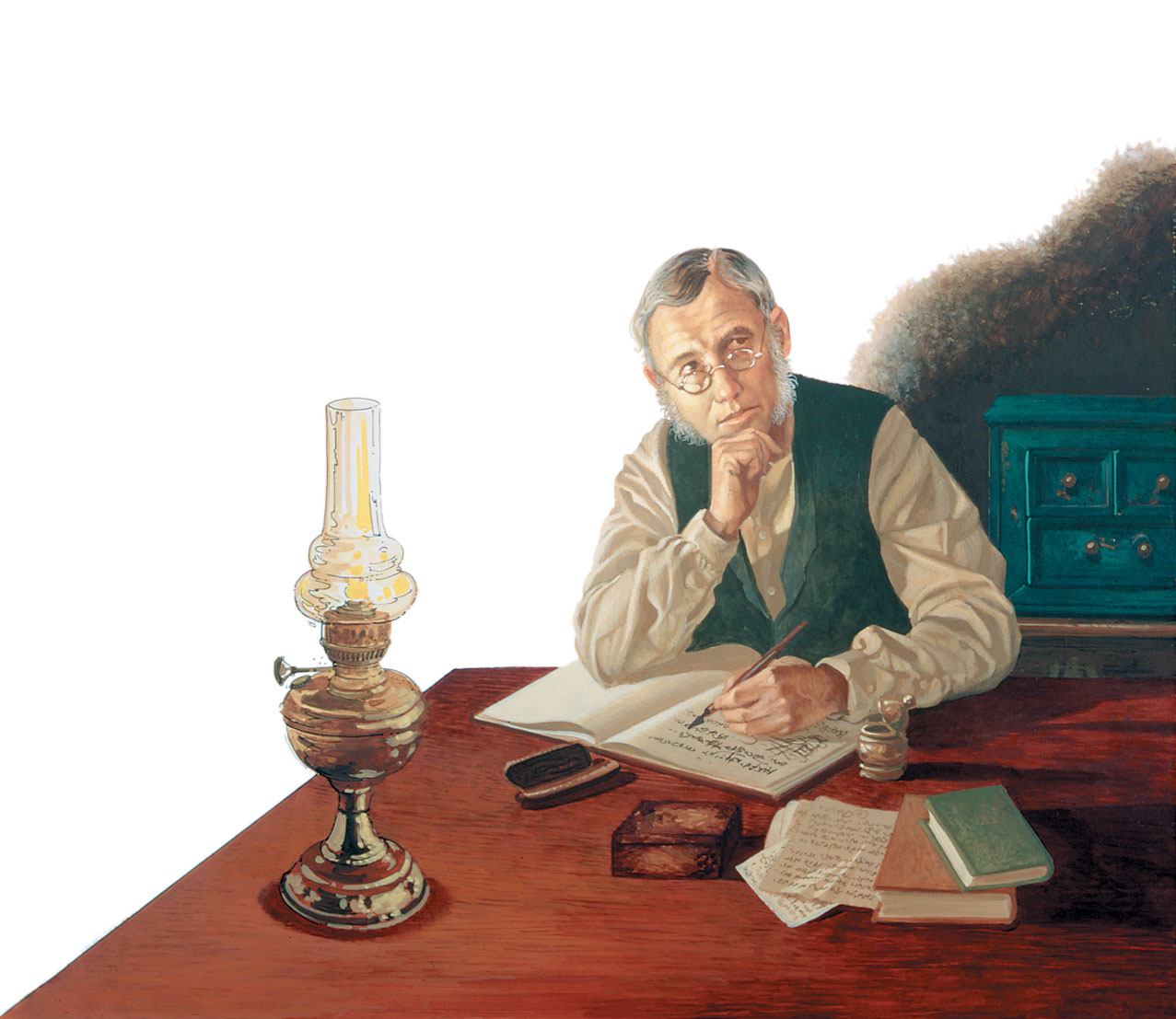

The text was a collaboration among Christensen and two Greenwich writers, Renwick St. James and Alan Dean Foster, and features Algernon Aisling, a professor of mythology and ancient legends who looks suspiciously like Christensen.

“I have to be true to who I am, just as Aisling must be true to who he is.” —James Christensen

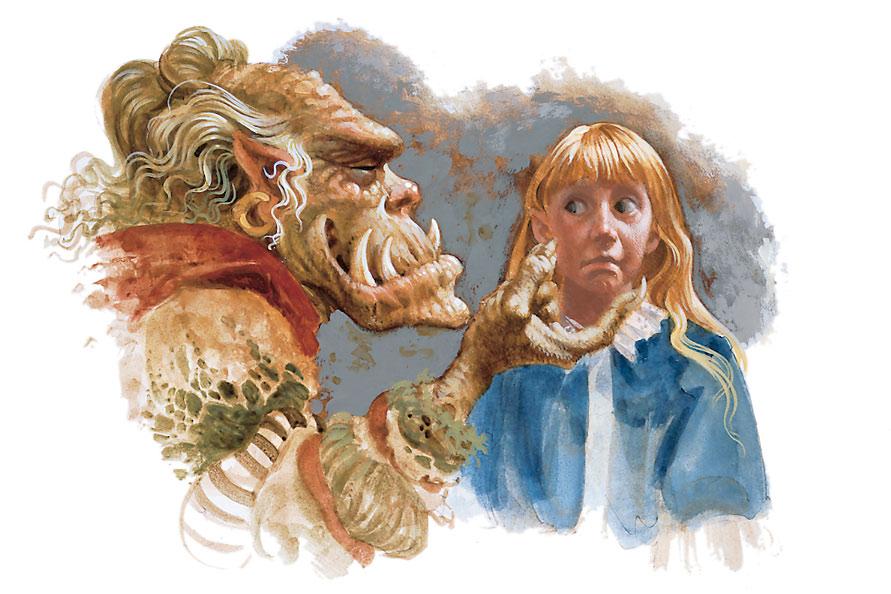

Aisling is a widower with two daughters—Cassandra, a precocious believer in magic, and Miranda, a sensible teenage skeptic who misses her mother and does not find much magic in her life.

Although, like Christensen, the professor believes imagination is where science begins, his view is not shared by all his colleagues. As the story begins, his department is threatened with closure.

The discouraged professor dreams of a ship that would transport him to the land of legends, and his fantasy becomes reality one evening when he and his children find an odd little ship moored alongside an abandoned dock. The enchanted vessel is fully staffed with dwarves and gremlins ready to take the Aislings on a journey of the imagination.

Happily, the ship leads him to the magical minotaurs, fairies, nymphs, gryphons, trolls, serpents, mermaids, unicorns, manticores, and other marvelous creatures of mythology. His compass is a wunterlabe, a mysterious device that carries him out of the rational world and navigates him through the landscape of imagination.

As long as Aisling follows the creed of Credendo vides, he discovers magic, wonder, adventure, and even love from one of the most unlikely mythological beings. But when he encounters solid scientific evidence of mythology in the form of a dragon skull, he begins to think about the fame and acclaim that will await him. In not being true to his original vision and succumbing to the applause of the world, he nearly undoes his mission and everyone accompanying him.

Christensen sees parallels to Professor Aisling in his own life.

“I have to be true to who I am, just as Aisling must be true to who he is,” he explains. “I am an illustrator, and I’m proud of it because it is important. I reject the philosophies of the elitist clique of New York art. That is a tunnel-vision world, and I’m in middle America. That is where my vision must lie and not with the acclaim elsewhere.”

Part of being true to that vision is his belief that life can be magical if you look at it that way.

“Consider fairies,” he explains. “They are magic and have always been with us—we need them.” His fairy muse is Beatrice Phillpotts, whose book, The Book of Fairies, inspired him. “When she explained the phenomenon of fairy painting in Britain, which flourished between 1790 and 1870, for example, she said their popularity was a reaction against the prevailing utilitarianism of the times. She wrote, ‘It was a celebration of magic in a period predominantly concerned with establishing facts. Darwin’s theories on Evolution and the Fall, the progress of Positivist thought, recent discoveries concerning the brain and the mind, all threatened the existing established framework of belief. Mystery was edged aside in a search for the kind of certitude afforded by experimental science. The postulation of an imaginary other world in art was an assertion of faith in the fantastic and irrational during a period of spiritual duress.’

“I, too, see imaginative potential in fairyland and other realms of the imaginary”—evidenced by Voyage of the Basset.

“Each painting became a new adventure.” —James Christensen

He says several illustrators have asked him how he stayed with the Basset project for so long. “I tell them the discipline I needed when I made a living doing freelance commercial work enabled me to have the concentration and fortitude to stick with Voyage.”

It also helped that he had strong feelings about mythology.

“I grew up in Southern California near the movie industry, and magic was always a big part of my life. By the time I was six years old, I knew all the legends and myths. I found the creatures fascinating; I still do. I hope my book helps others rediscover some pretty important characters that can add meaning to our lives.”

Although he enjoyed what he was doing, the task was laborious.

“Most of the time each painting became a new adventure,” Christensen explains. “But due to the sheer volume of work required, I sometimes felt like I did when I illustrated for the Ensign and had to draw two missionaries knocking on the door to find the widow ready to receive the gospel—and do it for the 700th time. It was work, hard work.”

Although he describes himself as “happily exhausted” and generally pleased with the result, he says he is never completely satisfied with his efforts.

“I don’t think I can really look at Voyage of the Basset closely for a while because I know where the bent nails are,” he explains. “Scott Gustavson, a popular illustrator, worked on Peter Pan for a couple of years and told me it was at least three years before he could look at the painting and enjoy it. I think in a year or two, I’ll be able to say about my book, ‘Hey, there’s much good work there.’”

He hopes the book will eventually become a movie or a television miniseries. He thinks the high interest and ratings generated by last year’s television presentation of Gulliver’s Travels could help him, and he has already had nibbles of interest from a major television network, a couple of major film studios, and others.

His ideal cast would include Sam Neill as Professor Aisling, Emma Thompson as Medusa, and the entire Monty Python ensemble as assorted characters.

“Hey, I know this is a fantasy cast,” Christensen says. “But then, I live in fantasy, which has created an awfully great reality for me.”

Although he credits BYU with giving him time and encouragement, the artist is so busy he plans to retire from full-time teaching in 1997 to handle the demands of his life as a professional artist.

“Being connected with BYU has always been immensely important to me,” he says. “It still is. On all my dust jackets, I go out of my way to list my BYU connection because the university has helped me immensely to develop as an artist. James Mason, the former dean of the College of Fine Arts and Communications, was at the core of supporters who said, ‘We are going to help you grow,’ and they did. The opportunities to create and teach and be surrounded by people with national art reputations has been a great payback.”

Christensen also cites the students as a major reason he has been with BYU for 20 years.

“I love teaching and communicating with those kids. It is such a thrill to see them succeed. One of my students, Greg Newbold, just published a book, and I had a book signing with him,” he says. “I love being part of that and sharing with my students. They have kept me vital, and though I’m retiring officially at the end of this year, I will maintain an affiliation with the university. I don’t know if I could bear the separation anxiety.”

He says he has a similar relationship with personnel at the Greenwich Workshop because they allow him considerable freedom to create what he chooses.

“Jim Christensen can do so many things; he could be his own cottage industry,” says Scott Usher, president of the Greenwich Village Press. “We enjoy having him be part of Greenwich, not only because he is so popular, but also because we all get infected by him and his magic.”

The artist calls himself a “20-year overnight success” who found his place in the artistic world by first painting a thousand bad paintings, followed by a thousand mediocre paintings followed by a thousand good ones.

As part of the artistic process, he made a transition from more traditional art styles—portraits, landscapes, still lifes—to fantastical art in the mid-1970s when he received a commission to paint one of “those crazy things stashed behind the desk.” He thought the magic fairies glistening with dew, the ornate hunchbacks that stared wisely from his canvases and the wizards and mythological muses draped in layers of elaborate fabrics dripping with jewels were simply for his personal enjoyment. Christensen soon learned there was an eager audience for this type of art.

He received another kind of validation in 1976 from the American Society of Illustrators when it gave him an award of merit for his allegorical image about death and the afterlife called “The Invisible Door.” Christensen says the award, the first of many, was important because it meant that a fantasy painting had been honored by the art community.

Christensen’s timing was an additional bonus. When he embarked on a journey of the imagination two decades ago, he was just ahead of a fantastical art movement that carried him with it. Among others, his art works have been used by NASA, Time-Life Books, Omni Magazine, and numerous book publishers. His work also has been seen in American Illustration Annual, Japan’s Outstanding American Illustrators, and in gallery shows countrywide.

Most recently, the famous New York City toy emporium, FAO Schwartz, commissioned him to paint the cover of its catalogue, and he has embarked on a nine-state tour to promote Voyage of the Basset. Eventually, however, he hopes to travel and replenish his imagination as he continues a life where everything is a possibility.