By Mary Lynn Johnson, ’91

After discovering rare personal records in a church archive, history professor Craig Harline has written vivid narrative accounts of two 17th-century Belgians.

AT first the archivist was the most formidable obstacle. An aging priest determined to protect his texts, Constant Van de Wiel was naturally skeptical—why, after all, would a young Mormon American be studying a 17th-century Belgian bishop?

History professor Craig Harline has spent much of the past 13 years reconstructing the lives of two 17th-century Belgian Catholics – Mathias Hovius, a busy archbishop, and Margaret Smulders, a Franciscan nun. According to Harline, their personal records reveal concerns and themes that apply to religious people even today.

Yet history professor Craig E. Harline, ’80, links the indomitable archivist with the most fruitful events of his research career. After all, it was in Van de Wiel’s archive that Harline encountered the extraordinary people who would become the subjects of his books.

Harline has spent much of the past 13 years reconstructing the lives of two 17th-century Belgian Catholics—Mathias Hovius, third archbishop of Mechelen, and Margaret Smulders, a cloistered nun from a Franciscan convent. Both were devout and opinionated, anxious to change their circumstances and improve the people around them. Both are remarkable to Harline not for their zeal or rank or wit or wealth but for the personal information that survives in records written by and about them.

“Here are people who lived 400 years ago, and their lives can still be relevant to mine or anyone else’s,” Harline says. “Something from their struggles and from their triumphs resonates with me.”

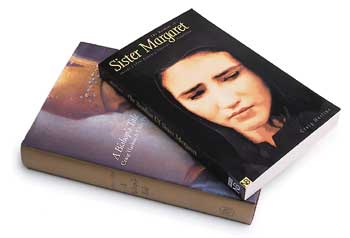

In an effort to share those insights—and the now-exotic cultural landscape of the 17th-century—Harline has written A Bishop’s Tale and The Burdens of Sister Margaret: Inside a 17th-Century Convent.

Meeting the Bishop

Published last year by Yale University Press, A Bishop’s Tale is the collaborative effort of Harline and Eddy Put, a senior assistant at the Belgian National Archives. The two men met in 1987 during Harline’s first research trip through Belgium. It was then, while visiting Van de Wiel’s largely unmined archive, that they happened upon the 400-year-old diary of Mathias Hovius.

The discovery of something unstudied and truly personal from the 17th century still excites Harline. Few people had reasons to keep personal records in those days, he says, and those who did often destroyed their papers before their deaths. In fact, it’s clear from the bishop’s diary that he had filled as many as 10 earlier volumes. Only the last survives, however, its entries dating from 1617 until his death in 1620. Yet even one such volume was a major find. In page after page of flowing Latin script, Hovius detailed the events and concerns of his ecclesiastical life. And soon after they began to read his diary, Harline and Put knew they had found the subject of a book.

Despite their enthusiasm, the book was not written quickly. Harline, then a new professor at the University of Idaho, could only work in Belgium during the summers, and things proceeded slowly until he gained the archivist’s trust. But after more than a few vacations spent poring over fragile manuscripts in Mechelen and at other European archives, Harline and Put constructed a vivid narrative portrait of their bishop.

Mathias Hovius led the archdiocese of Mechelen from 1589 to 1620, during a time of widespread conflict between Catholics and Protestants. He viewed his world as a spiritual battleground on which he struggled to preserve faith in the face of persistent attacks from heretics, wayward priests, and other troublemakers. His speech from a 1607 church council reveals urgent concern: “Seeds of heresy have sprouted in many souls. Pernicious books land in unsuspecting hands. Brothers, neighbors, and friends across the border live in captivity and in peril of their salvation” (A Bishop’s Tale, p. 112).

Hovius worked constantly to restore order and piety where they had lapsed. His records report his handling of thousands of crises involving a broad cast of characters: a recalcitrant heretic who was buried alive, jealous booksellers falsely accusing each other, clever Jesuits starting a school on the sly, a corrupt priest promoting relics of dubious origin, pastors both poor and greedy, resolute converts, miracle workers, irreverent sailors, and a host of other colorful characters, both savory and unsavory.

“Though we envy still the novelist’s total freedom of invention,” Harline and Put wrote, “we were consoled repeatedly by encounters with characters and events more improbable than we ever could have imagined ourselves.”

Hearing the Nun

One of the strongest characters Harline met among the bishop’s papers was Margaret Smulders, a by-some-accounts renegade nun from a small Belgian convent. Her letters (written between 1616 and her death in 1648) survive in the papers of Hovius and his successor, Jacob Boonen. “One of those letters is 32 pages,” Harline says. “I’ve never seen a personal letter like that in this period, by a nun or anybody else.”

For reasons only partly decipherable through the records, Sister Margaret lost favor with many of her peers and leaders within the convent. At the vote of the other sisters, she was banished to the convent guesthouse for years at a time. Her letters were written from that solitude, and they beg the bishop for attention and aid.

“Most Reverend Lord, if we had a Mater who was a lover of true religious life, observing and enforcing the praiseworthy statutes and wise ordinances of your reverence, given through the Holy Spirit, then there would be no need for any of us to trouble and burden your reverence.” Thus begins Margaret’s 32-page missive, penned in 1628 in anticipation of an official visit. She goes on to critique her convent on a range of subjects, from expenses to favoritism to waffle baking.

“I loved those documents,” Harline says. “They could have been part of the story of the bishop, but they really deserved their own book.” The result was The Burdens of Sister Margaret: Inside a 17th-Century Convent, published in 1994 by Doubleday and (in a revised, paperback edition) by Yale University Press in 2000. The 1994 version has been translated into Dutch and Swedish.

Seeing a World in a Grain of Sand

Harline’s approach is called “microhistory”—an effort to understand the past by making it particular. “The whole point of microhistory is that you go to a specific place and try to get a sense of how it smelled,” he says. “But then you always stop and connect it to bigger themes.”

Heiko A. Oberman, regents professor of history at the University of Arizona, says Harline’s work brings the 17th century to life. “You are living in the houses of the people, escaping with the soldiers, hungering with those that are hungry, and because of that detail, you identify with the characters. That is the way history should be.”

For Harline, the issues his subjects faced in 17th-century Belgium are real among modern Latter-day Saints.

“In Sister Margaret you’ve got all kinds of religious issues going on,” he says. “She’s supposed to give up her will for the sake of the community, but how far can you do that? Ideally you withdraw from the world, but you still have to buy coal and food and things. Being in the world but not of the world, individual spirituality versus the communal demands, obedience and initiative: Those are struggles that any religious person can relate to.”

And that, after all, is the point. In his research and teaching, Harline focuses on specific, complex individuals in order to help others relate to the past—and, ideally, understand the present in greater depth.

“Something that happened 400 years ago or 1,400 years ago can be just as relevant as something that happened four years ago,” he says. “People tend to think that more relevant history is recent history, and that’s not always true. Any past can matter.”

More info: Translations of Margaret Smulders’ 32-page letter (quoted above), other letters from the nuns, and excerpts from The Burdens of Sister Margaret can be read on Harline’s Web site: fhss.byu.edu/ history/faculty/harline/index.html.