In the war-torn mountains of Afghanistan, an American chaplain and a militant-trained Muslim mullah break through cultural barriers.

EDITOR’S NOTE: In recent years many BYU alumni and student soldiers have been called upon to serve in war zones and relief efforts. This article and its sidebars share some of their stories. Read more stories (and add your own) at more.byu.edu/military.

I am Maseullah, the Afghan Security Forces chaplain. You are at the Americans’ clinic. They will take good care of you. I promise. They are good men. God is Great.” Kneeling next to a bleeding man lying prone on a cot, Maseullah spoke in soft Pashtu tones that Wadir, our local interpreter, or “terp,” later translated for me.

Two injured Afghan men had been brought by truck to Camp Blessing, an Army Special Forces A-camp that overlooks the fertile Pesch Valley high in the Hindu Kush Mountains near the Pakistani border. Afghans had jumped out of the truck, scurrying the two limp bodies on blood-soaked improvised stretchers into the clinic.

As the special forces medic, Medic Mike as he was known in Afghanistan, began cutting off the ripped shreds of the men’s jamas, Wadir explained,

“An explosion . . . on the road . . . four kilometers from here.” Their exposed backs revealed hundreds of rock fragments embedded deep into their flesh. Mike reached for disinfectant and needle-nose pliers.

Maseullah had come straight to the clinic, just as I had taught him to do. Together we worked to comfort the two injured men, distracting them while medics removed rocks and dressed wounds. Each time the pliers went in, my man gripped my hand. Except for the sound of his occasional sharp breaths drawn in through clenched teeth, he remained silent. Sometimes he would look at me, nod, and whisper something in Pashtu, but mostly he just stared ahead.

Sergeant Scott, the camp intelligence operative, entered the clinic as the treatment continued, snapping pictures with a digital camera and asking questions. The patients claimed to be workers who had been using dynamite to widen a road; they said a short-fused explosive had detonated early, hurling debris at their backs as they ran for cover. But he knew they might also have been injured in a bungled attempt to plant an improvised explosive device under the road to blow up a convoy. Al-Qaida’s training manual on tactics and propaganda taught that injured operatives should seek Americans’ high-quality medical treatment and later claim torture. Scott now knew their names, their faces, and their home village. And with the pictures, he had evidence of their good treatment. Maseullah later said that, whoever the men were, they would remember our care and be more likely to support the new democratic government of Afghanistan.

As the battalion commander’s liaison to local religious leaders and as Maseullah’s mentor, I was pleased with how he comforted the injured man. For the preceding several weeks, we had been conducting instruction on Maseullah’s role as a chaplain to the Afghan Security Forces soldiers we were training at Camp Blessing. There had been no shortage of opportunities to practice the scenarios we had drilled in our lessons—providing services for soldiers in the field; overseeing mosque restoration; giving an invocation for Camp Blessing’s naming ceremony; and leading an appropriate Islamic prayer with townspeople whose son had been too close to an air strike against terrorists.

As the battalion commander’s liaison to local religious leaders and as Maseullah’s mentor, I was pleased with how he comforted the injured man. For the preceding several weeks, we had been conducting instruction on Maseullah’s role as a chaplain to the Afghan Security Forces soldiers we were training at Camp Blessing. There had been no shortage of opportunities to practice the scenarios we had drilled in our lessons—providing services for soldiers in the field; overseeing mosque restoration; giving an invocation for Camp Blessing’s naming ceremony; and leading an appropriate Islamic prayer with townspeople whose son had been too close to an air strike against terrorists.

In a lesson just the day before we ministered to the two injured men, we had discussed the chaplain’s responsibility to the wounded.

“When you go to minister to an injured person, tell them who you are and what is going on,” I had explained. “You are a symbol of God’s love and watchfulness over soldiers.”

“It’s curious,” Maseullah had responded, “but even my soldiers who are not very good Muslims like seeing me. They seem more calm when I am around.”

“That’s because they can see you are a peaceful person right with God. This makes them feel secure. That is why they chose you as their mullah,” I had said, referring to his role as his soldiers’ elected pastor.

Embarrassed by my compliment, he had laughed his low easy rumble and looked away, stroking his long black beard with his big calloused hands.

Maseullah would often tell me that it was the will of God that we had come together. Captain Ronald C. Fry (BS ’96), Camp Blessing’s commander (known in Afghanistan as Commander Ron), introduced us while I was on one of my scheduled visits to provide general Christian services and counseling support to the many A-camps our battalion had established along the border. “Our Afghan soldiers have a chaplain too; you should meet him,” Commander Ron had said. Thus began, as far as I know, the first-ever chaplain training program undertaken by the Army Special Forces, whose forte is training indigenous counter-insurgency infantry.

Maseullah would often tell me that it was the will of God that we had come together. Captain Ronald C. Fry (BS ’96), Camp Blessing’s commander (known in Afghanistan as Commander Ron), introduced us while I was on one of my scheduled visits to provide general Christian services and counseling support to the many A-camps our battalion had established along the border. “Our Afghan soldiers have a chaplain too; you should meet him,” Commander Ron had said. Thus began, as far as I know, the first-ever chaplain training program undertaken by the Army Special Forces, whose forte is training indigenous counter-insurgency infantry.

Though our backgrounds—a militant-trained Afghan mullah and an American Christian chaplain—might make us seem unlikely friends, Maseullah and I shared an almost instant bond of purpose.

As a child, Maseullah’s parents sent him to live and study at a madrassa, or religious school, in Pakistan. Maseullah returned home as a hafiz—one who can recite the whole Koran from memory. His instructor’s charge still rang in his ears, “America is the great Satan. Go forth from here and drive out the infidel occupiers, and God will sanctify you.”

My training led me to become a folklore professor at BYU, a different kind of religious institution halfway around the world. Knowing something of the history of tyranny and how the educated have typically been the first to be singled out for torture and execution, I realized that no one enjoys the benefits of political and religious freedom more than scholars. I felt that my personal freedom was not a given I could take for granted, but something for which I was deeply indebted. One way to at least pay down some interest on this debt was to help secure for others the freedoms I enjoyed. So I joined the First Battalion of the Utah National Guard’s 19th Special Forces Group as their chaplain, and the U.S. Army sent me to Afghanistan to provide and coordinate religious support for soldiers. Like Maseullah, I too came to the Pesch Valley charged to fight for a cause.

Under Commander Ron’s proactive implementation of the military’s policy of respect for local religious practices, Maseullah had begun to question aspects of his religious training and joined the Afghan Security Forces. When my assistant and I arrived in the Pesch Valley with a plan to employ local craftsmen to restore damaged and rundown mosques in villages that supported coalition efforts and invited Maseullah to be our special advisor, the idea of Americans as crusaders come to destroy Islam began to make even less sense to him.

Through the eyes of Maseullah and other Afghans, I witnessed how freedom from tyranny was affecting peoples’ lives. I saw refugees returning from Iran and Pakistan to their homes. I worked with members of an Afghan women’s group, no longer hunted and murdered by the Taliban, now operating freely for the benefit of Afghan women. I listened to people excitedly discussing, for the first time in their lives, differing opinions about candidates in upcoming elections. I saw girls going to school for the first time. I watched independent farmers freely planting lucrative crops the Taliban had monopolized for themselves.

Villagers we talked to on patrol denounced the Taliban remnants and their al-Qaida allies as “parasites that corrode civilization” and “apostates who shame Islam.” Maseullah spoke often about how much he enjoyed his training and how much it meant to the locals that the Americans in his valley were taking their religious desires seriously.

As the Taliban regime crumbled and retreated into the hinterlands of Afghanistan, Maseullah increasingly saw the benefits of freedom for his quiet and serious form of Islam in a country where devotion and piety might be freely chosen rather than coerced by the Taliban’s religious police. As a token of our friendship, one day Maseullah gave me wildflowers while on patrol with our soldiers. (This is common for Afghan male friends but unusual to say the least among the Army Special Forces.)

Recognizing the benefits of freedom for oneself is one thing, but I knew that allowing others to exercise freedom in ways we personally despise is quite another. So one day, after we had worked together for some time, I sprang a role-play scenario on Maseullah. As we sat on floor mats drinking green tea (warm milk in my case) surrounded by the vast but spartan Russian-built concrete walls of Maseullah’s simple room in the ASF compound, I began, “Someday the Pesch Valley Security Forces may be rolled into the Afghan National Army, and you might be a chaplain for soldiers from all over Afghanistan. Maybe there will be Hazaras from Bamiyan province in your unit.”

To help the terp, I pushed in my nose. Maseullah laughed to show he knew what I meant. Despite now being the bottom-of-the-totem-pole ethnic group in Afghanistan, the Hazaras revel in their claimed descent from Genghis Khan’s hordes. The long, thin noses typical of, and attractive to, Pashtuns like Maseullah could not present a greater contrast to typical Hazara faces.

I had chosen this group intentionally. From the radical Sunni point of view, the Hazaras were mushrikeen, or heretic Muslims, worthy of nothing but the point of a sword. Just five years before, Taliban extremists who had studied at the same kind of madrassa Maseullah had attended systematically massacred thousands of Hazaras in Bamiyan province. A few years later, the Taliban had destroyed Afghanistan’s greatest artistic and historic treasure, the gigantic stone Buddahs of Bamiyan. The Taliban did not care about pluralism, religious freedom, or architectural heritage. They saw such ideas as corrupting Western influences that had to be wiped out so they could impose their own ideas of proper Islamic purity.

“What would you do if Hazara soldiers came to you saying they wanted to take leave to celebrate Ashura?” I made the motions of swinging a whip across my back and cried, “Hussein! Hussein!” like the Shiite Hazaras do in dramatic bloody processions to commemorate the betrayal and martyrdom of their beloved imam on their most important religious holiday.

This time Maseullah didn’t smile. “I know what I believe, and as a Sunni I do not agree with these practices. But only God can judge. My job as a chaplain is to see that people are free to practice their religion. I would ask the commander to respect their wishes and let them go celebrate. The Afghan Army should be for all Afghans. Only God can judge. Only God can judge.”

This moment was one of the most satisfying of all my time in Afghanistan. It pointed toward the possibility of peaceful coexistence even in a world full of people trained for tyranny, as Maseullah had been.

But I had another fear. By taking Maseullah on as a student, was I making him a marked man, a collaborationist who would be punished in some public and grisly way? If our forces pulled out before the job was done, what would be his fate? I would go home far away to the security of my home in America. Maseullah went home every night to a small mountainside abode to his wife and four children. They would be easy to find.

Despite my fears for him, Maseullah boldly pushed beyond what I had asked him to do and astonished me with his bravery. One day, as I returned to Camp Blessing from a meeting with village elders about mosque reconstruction work, Maseullah jumped up to greet me from where he had been waiting at our dusty outdoor mess table next to the motor-pool yard. I had not seen him for some time.

He told me he had just returned from a trip to Pakistan to visit his old madrassa. He had hiked 40 miles through some of the most dangerous territory in the world to see his former teachers. Much of the ideological fuel sustaining the terrorists continued to pump out of the same sort of place Maseullah had gone back to.

He told me that in Pakistan he had sat down with his teachers. “I am working with the Americans,” he confided. “They have supported me as chaplain over the Afghan Security Forces in my valley, and we are doing great things together. They are not the crusaders you said they were.”

His astonished teachers replied to his tale, “We don’t believe you, Maseullah. Surely you have been duped by their crafty deceptions. All Americans do is try to destroy Islam.”

“Then why are they restoring mosques all over my valley, and why are they allowing me to make sure my soldiers pray five times a day?”

“Surely none of this is true, Maseullah,” they insisted. “You must be joking with us.”

“No, I am not joking. Come see with your own eyes. Come to my valley and see it dotted with the newly painted minarets the Americans have helped us restore. With respect, you were wrong about them.”

Such tenacious preconceptions aren’t changed easily. While a transition was kick-started by the American response to Sept. 11, it was clear to me that its continuing momentum was only made possible by Afghans like Maseullah willing to risk their lives to change minds. I asked him why he was willing to do this.

He said, “It is the principle of in sha’ allah.”

I knew in sha’ allah. I’d heard it a lot. It means, “If God wills.” American soldiers tend not to like this common Arabic phrase. To American ears it often sounds like an easy way to wriggle out of commitments or to avoid personal responsibility for failing to finish promised undertakings. But as Maseullah explained it, this concept seemed liberating, empowering, and a part of the solution—a great key to peace amid conflict between countries or in the troubled recesses of our own hearts.

“You see, Chaplain, whether I live or die is no matter. I will die when I die, and I hope to die while doing what is right—regardless of the dangers. It is all in God’s hands. We are working together, you and I—a Muslim and a Christian working together to conquer those who don’t like the idea of a Muslim and a Christian as friends here in Afghanistan or anywhere in the world. If God wills, we will prevail, so we need not fear.” I sensed a great lesson in this for both America and the Muslim world in these times of trouble. Without fear there is hope. With hope there is peace. In sha’ allah.

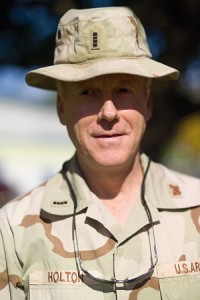

Eric Eliason, an associate professor of English at BYU, serves as a chaplain with the 1st Battalion 19th Special Forces Group (Airborne) in the Utah Army National Guard.

>> A FIRST STEP

By Kevin L. Stoker (BA ’81)

DURING SPARE MOMENTS in his 13-month deployment to Iraq, Paul R. Holton (BA ’77) did what a lot of soldiers were doing—he posted his daily journal on a Web log, or “blog.”

Using the pseudonym “Chief Wiggles” for security purposes, the chief warrant officer in the Utah Army National Guard’s 141st Military Intelligence Battalion described interrogating former Iraqi leaders and fulfilling other assignments in Iraq. The blog (now published in the book Saving Babylon) first drew 10 to 15 family members and friends, but soon others, including the news media, began linking to his site, helping it notch up to as many as 15,000 visits a day. One entry about a simple act of kindness would change the life of Holton, along with countless others around the world.

“One day I knelt down and handed out a little stuffed monkey to an Iraqi girl,” Holton says. “I realized that this was one thing I could do over and over again and bring a little sunshine into the lives of these children and let them know that the Americans were there to help.”

He posted his experience on his blog and urged people to send toys. The response soon overwhelmed him and the Army’s mail system. “Hundreds and hundreds, then thousands of boxes of toys showed up, so many that the Army’s lawyers sent a cease-and-desist order because we were blowing out the system,” Holton recalls.

To bypass the Army’s system, Maryland attorney Matt Evans, a reader of Holton’s blog, formed the nonprofit organization Operation Give and soon began sending containers of toys by ship to Iraq from an East Coast warehouse. Holton’s Utah employer, FedEx, also helped by offering free shipping to the warehouse and later to the Middle East.

Meanwhile, Holton commandeered a bus formerly owned by Saddam Hussein to carry toys to hospitals and orphanages throughout Baghdad.

Holton’s story was covered by CNN and other U.S. news media and President Bush honored him at a National Prayer Breakfast in February 2004. Through Operation Give, toys, school supplies, and hygiene kits have been donated to children in Iraq, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, and parts of the United States affected by Hurricane Katrina.

“If I were going to have a positive experience in Iraq, it would be because I wanted to take the first step,” says Holton. “Then, all of a sudden, thousands of people took a step with me.”

>> BUILDING RESPECT

By Kevin L. Stoker (BA ’81)

AFTER COMPLETING ENGINEER OFFICER BASIC COURSE, 2nd Lt. Sonie Foster Munson (BS ’03) shipped out for four months in Iraq, assigned to a combat-heavy engineer battalion and stationed at LSA Anaconda near Balad, Iraq, some 50 miles north of Baghdad.

She took command of a “vertical” platoon, constructing buildings and pouring concrete. It wasn’t the kind of job one might expect for someone who had earned a degree in wildlife and range resources, and Munson knew she had to prove herself as an engineer.

When Iraqi contractors came on the post looking for jobs, they were surprised to find a woman in charge.

Munson became accustomed to being the only woman, even at worship services for Latter-day Saints. “They always said, ‘Good morning, brothers and sister.’”

Her soldiers knew she was different than most other officers. They would come and talk to her about their problems and ask her questions about the Church of Jesus Christ. Munson earned their respect by toiling behind the scenes to solve supply problems and working side by side with them, swinging a hammer and pouring in concrete. She knew her soldiers liked her when they put her through the unit’s initiation ritual.

“One of the squad leaders slammed me into wet concrete and then the other guys shoveled concrete on me until I was completely covered,” she says. “They videotaped the whole thing and when they had washed the concrete off of me, they said, ‘Congratulations, you’re an engineer.’”

>> LENDING A HAND DOWN SOUTH

By Kevin L. Stoker (BA ’81)

WHEN LT. COL. DALLEN S. ATACK (BS ’88), battalion commander of the Utah Army National Guard’s 1-145th Field Artillery, recalls his most recent deployment, he tells of looking off the side of the road at night and seeing hundreds of alligators looking back at him and of cleaning out a school and killing more than 75 poisonous snakes. But, called upon in the wake of Hurricane Rita, Atack says the bond he developed with the Cajun people of Louisiana left the deepest impression on him.

“It was the most rewarding month I ever spent in the Army, and I’ve spent 19 years in the National Guard,” Atack says.

Rita struck Saturday, Sept. 24. That night Atack received the call to mobilize his battalion. Five days later, 230 Utah soldiers with 35 support vehicles moved into an abandoned Catholic school in Abbeville, La., and began patrolling the streets.

The battalion’s primary mission was security as locals returned to Abbeville and other areas of Vermilion Parish. Additionally, groups of 50 soldiers were sent on daily missions to places such as the Cajundome in Lafayette, La., which was a home for Hurricane Katrina evacuees, and Baton Rouge, where armed robberies plagued the Red Cross’ distribution of debit cards.

Atack says his soldiers often worked their security shifts only to then spend hours cleaning schools, parks, and churches. One group that had just returned from a 12-hour security shift and a two-hour bus ride from Baton Rouge was met by the parish priest who asked them to clean out a chapel and cemetery lawn for a funeral the next day. The soldiers worked another six or seven hours.

“On the last day we were in Abbeville, the parish father came and gave us a blessing for our next mission,” Atack says. There were other acts of gratitude, like being the honored guests at a University of Louisiana at Lafayette football game.

“As we provided security for them,” Atack says, “they provided a home away from home and Southern hospitality.”

>> FIRST DAY IN BAGHDAD

By Kevin L. Stoker (BA ’81)

ON APRIL 8, 2003, the day U.S. ground troops entered Baghdad, Mark A. Patterson’s (’06) Marine platoon walked into Saddam City (now Sadr City) as part of a “presence” patrol.

“What that really means is we walk around and let the enemy shoot at us so we can see where they are,” says Patterson, a political science major. A native of Charlottesville, Va., Patterson said that day in Baghdad galvanized his faith in American ideals.

Enemy fighters, firing rocket-propelled grenades, ambushed another platoon on a street corner, wounding several soldiers. Patterson’s platoon moved up to reinforce the beleaguered marines.

“The enemy were stopping civilian cars and using them as cover,” Patterson says. “When we had taken cover, we were shooting literally through these people at the enemy. The enemy used civilians as human shields so often; it was their tactic, and we always expected it.”

If the use of human shields failed to stop the marines, the enemy would use cars full of people as battering rams.

“During a lull in the battle, five marines, some of my best friends, ran across 500 yards of open space to rescue any civilians still alive,” Patterson remembers. “Most of the people they found were dead, but one guy was still alive, and they dragged him back to safety.”

After the battle, while taking care of wounded civilians, Patterson’s squad treated and evacuated a girl shot in both arms. The girl’s family then welcomed the marines into their home, fed them, and housed them for the night. The next morning, the homeowner, a dentist, wanted to know if the marines would really get rid of Saddam Hussein.

“We told him we were there to fix his country, and then we were going to leave,” Patterson remembers. “The guy started to cry and grabbed this marine and kissed him on both cheeks and thanked him.

“These people risked their lives to help us. They were so willing, so grateful.”

Read more stories from BYU alumni and student soldiers who have served in war zones and relief efforts or share your own at more.byu.edu/military.

FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

MORE MILITARY STORIES

By Kevin L. Stoker (BA ’81)

Many BYU alumni and student soldiers have served in war zones and relief efforts. Read their stories and add your own by e-mailing it to magazine@byu.edu.

Healing Bodies and Souls

By Kevin L. Stoker (BA ’81)

For some soldiers severely wounded in Iraq and Afghanistan, Army Capt. Brian Belnap (BS ’97) and his staff at Walter Reed Army Medical Center are the first people they see after losing consciousness or being sedated at the battle scene.

“You almost feel like you’re on the battlefield because they get here so quickly,” says Belnap, chief and director of inpatient rehabilitation. “In Vietnam, it took a few months for the wounded to get here, but now it’s a matter of days. We’re dealing with the psychological trauma brought on by their injuries, not to mention the physical trauma.”

A rehabilitation specialist, Belnap runs the amputee service. He works alongside Scott B. Shawen (BA ’91), an orthopedic surgeon.

“It opens your eyes to the horrors of war,” Belnap says. “It’s not uncommon to see amputees under our care go through divorces. We’ve seen family coming in and not being able to handle what’s happened to their loved ones and leave them. We’ve also seen amazing stories of people standing beside them, despite the seriousness of their injuries.”

Belnap has also seen great courage in the amputees. Despite having his leg amputated above the knee, one sergeant went around from room to room lifting the spirits of other amputees, some less seriously injured than he. Once mended, the sergeant re-enlisted and is now on active duty.

“We have a spinal cord patient in the special forces who is paralyzed completely, and yet he is extremely upbeat and happy to be alive,” Belnap says.

Belnap says his work has been humbling and spiritually rewarding, giving him a deep sense of gratitude for the soldiers’ sacrifices. One soldier had stepped on a landmine and lost his leg. His fellow soldier, in coming to the rescue, set off another landmine and lost his leg in turn.

“The first guy had such a hard time dealing with it,” Belnap says. “I had many heart-to-heart conversations with him. He got better, not only physically, but spiritually.”

Caring for Enemies

By Kevin L. Stoker (BA ’81)

For William C. Dunaway (BS ’63), a BYU Health Center physician, the nightmare began on his first evening in southern Iraq at the Camp Buca prison, about 50 miles from Basra. With floodlights illuminating the desert, Dunaway had the surreal feeling that he had walked into a Friday-night football game rather than a prison camp housing 6,000 prisoners.

As he approached the razor-wire-walled compound, Dunaway’s senses were bombarded by his surroundings. Dunaway recalls the lights, the 120-degree heat, the yelling, and the smell: “It was like you’d died and gone to hell.”

Dunaway went to Iraq as a battalion surgeon, but once there he assumed the larger duties of a brigade surgeon, overseeing the medical needs of the 6,000 prisoners and 2,000 military personnel at Camp Buca. From the start, he made sure the prisoners were treated well, despite the sweltering, often unsanitary conditions.

“We’d drag boxes down the road, and they’d bring the prisoners up, and we’d just sit right there in the dirt and treat them,” he says. “They had gunshot wounds and everything else.”

Dunaway made sure the doctors, physician assistants, and medics under him treated the prisoners well. “I said, ‘You can’t tell who’s good or bad. Let God sort it out.’” Dunaway remembers that, along with the International Red Cross, one female major in particular watched out for the prisoners. “She was a Mother Teresa type—I’ve never seen a more Christlike person,” he recalls. “She worked a minimum of 14 hours a day, every day. She went to bed about 1 a.m. and was up by about 6. Nonstop service.”

Often the prisoners expressed gratitude for the medical attention. “I’d have prisoners kiss my hand when I’d treat them, they were just so thankful. At BYU nobody kisses my hand, even if I make the right diagnosis. That was neat to have somebody be that grateful.”

When the Sirens Sound

By Kevin L. Stoker (BA ’81)

Captain Sarah Leseberg Ralston (BA ’99) knew the drill. Years of training had made it routine. When the air-raid sirens wailed, she donned her chemical equipment—boots, gloves, pants, mask, and body armor—and waited.

But the first alert at Kuwait’s Camp Doha, coming just two hours after she arrived in March 2003, was unlike training. The sirens sounded and she put on her chemical equipment, but she said she failed to grasp what was happening until she “heard this big roar.” With no airplanes stationed at Camp Doha, the roar had to have come from the firing of a Patriot missile.

“I could taste metal in my mouth,” she recalls. “It’s like when you’re almost in a car accident, and you just miss being hit. I had that same near-miss fear. I was frightened for a minute and then I was OK.”

The alerts continued for the first two months of the war. Ralston, who commands a Patriot missile battery at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, said people in Kuwait and Iraq had a lot of confidence in the Patriots, believing they could hit anything.

“People who work with the Patriot missile system have far less faith in it than those who don’t,” she says. “We did hit everything fired at us, but it is a machine and it has its limitations.”

Among those missiles shot out of the sky was one aimed at the headquarters housing Ralston. From this and other experiences, Ralston says she learned the importance of good leadership, especially under fire. Some that she thought would handle the fear well did not, and others fared better than she expected. Ralston says she showed fear but found she functioned well in spite of it.

“Every time the sirens went off, my mind went in five different directions,” she says. “Part of me prayed. Part of me said to put on my pants, top, boots, gloves, and body armor. Part of me said to run to the bunker for cover, and part of me was cussing, too. But I always had a prayer.”

Finding Birds amid the Battle

By Kevin L. Stoker (BA ’81)

In January 2003 Landon R. Jones (BS ’05) started classes at BYU, got engaged to Amanda Williford (BS ’02), and planned for an April wedding. A sergeant in the 141st Military Intelligence Battalion of the Utah National Guard, Jones had been assured by his commander that translators would not be deployed.

But on Tuesday, Jan. 21, he found out he was one of the last of 200 to be activated, not with his unit but as part of Utah’s 142nd Military Intelligence Battalion.

“They don’t need you,” Amanda was quoted in the Daily Universe as telling him. “I need you. You’re just a wimpy French translator.”

On Wednesday the couple leaned toward delaying the wedding for a year. On Thursday they decided to tie the knot right away. On Friday their parents drove up from California. On Saturday they were married. Forty-eight hours later, Jones shipped out for Fort Carson, Colo.

Once in the Middle East, Jones spent a little more than a month in Kuwait before heading for Tikrit, Iraq. Stationed in one of Saddam’s palaces on the Tigris River, Jones pursued a hobby that he had picked up from a class at BYU.

“We had this big picture window that looked out over the Tigris,” he says of the Tikrit palace. “Every few minutes I was grabbing somebody’s binoculars and picking out birds. I’d walk the palace grounds watching birds.”

The army moved him to Qatar for the last eight months of his deployment. He supervised Arabic linguists and spent all his free time bird watching.

“Iraq is full of great birds,” Jones said. “In Qatar you see a lot of birds even in the sparsest environment.”

Jones retained his passion for bird watching after returning to BYU. After finishing his degree in conservation biology, he entered BYU’s wildlife biology master’s program. His emphasis? Ornithology.

Coming Home

By Kevin L. Stoker (BA ’81)

When Robyn Felsted Scoubes (BS ’01) first learned that her husband, Keir A. Scoubes (BS ’01), was headed to Iraq, she was worried. They had three children and a fourth on the way.

“Then we went to the temple, and I just had a feeling it was going to be all right,” she says. “Because of our belief, whether he is home in a year and a half or in 60 years, he’s still coming home. The eternal things were taken care of.”

A member of the 142nd Military Intelligence Battalion of the Utah National Guard, Keir, then a first lieutenant, shipped out in January 2003 to Fort Carson, Colo., and deployed to Baghdad in April.

“For Keir’s sake, we didn’t want him worrying about us,” Robyn says. “I just told him, ‘When you’re done, we’ll be here.’ That’s how you do it. If you lament, if you cry, you just make it harder.”

At night, she was too tired to feel lonely. She spent the summer of 2003 with her parents in Great Falls, Va., and the baby was born in Bethesda Naval Hospital. Keir took part via speakerphone.

To lift her children’s spirits, she portrayed their dad’s service as a “cool opportunity” to help people. Meanwhile, she took comfort in Keir’s training and leadership role.

Sixteen months after leaving, Keir returned home in May 2004 and now teaches fifth grade at Larsen Elementary School in Spanish Fork, Utah.

In the end, the couple says the sacrifice was worth it. Both came away improved and prepared for Keir’s new calling as bishop.

“That’s how it changed me,” she said. “I’m not sure how good of a bishop’s wife I would have been if not for the year and a half he wasn’t here. I learned that I could do dinner, get homework done, and put the kids to bed. At this point, having him away as bishop is nothing. At least I know he’s coming home.”