Learning the Y

In a game-changing new general-ed course, students dive deep into BYU’s distinctive mission and find their place in a community of belonging.

By Peter B. Gardner (BA ’98, MA ’04, MBA ’22) in the Summer 2024 Issue

Fraught.

That’s the word that comes to BYU dean of undergraduate education Richard A. Gill (BS ’93) when he thinks of the transition to college life. “It’s that beautiful first-year tension between ‘I’m so excited’ and ‘I’m so scared.’” The typical new freshman comes preloaded with worries—about keeping up in the classroom, finding friends, and discerning what an uncertain future holds.

Student-success offerings—orientations, resource fairs, seminars—have become standard at modern universities, BYU included. But a new class in Provo is taking onboarding to a whole new level—delving deep to explore the university’s foundations.

“Nobody has anything like this,” Gill asserts.

UNIV 101: BYU Foundations for Student Success—piloted in 2023 and officially launched in winter 2024—is a far cry from a simple student-resources course. Instead, it’s geared to dig into seminal addresses, anchor students in BYU’s prophetically guided mission, and forge a covenant community of belonging.

“If we’re going to become the Christ-centered . . . university of prophecy, our students had better understand what’s been foretold about this place.”

—Rich Osguthorpe

It’s also unique in scope, says Gill. The general-ed course will be required for every first-semester student—7,000 of them in a typical fall semester.

Nor is any other university dedicating hundreds of tenured faculty—including deans, vice presidents, and even the university president—to such an endeavor. Those behind the course say the investment makes sense when you consider its lofty objectives.

“We have a responsibility to help our students understand the prophetic vision for BYU,” says Richard D. Osguthorpe (BA ’98), an associate academic vice president and UNIV 101 teacher. “If we’re going to become the Christ-centered . . . university of prophecy, our students had better understand what’s been foretold about this place.”

One semester in, students and faculty alike are giving the BYU primer rave reviews.

“We’re changing faculty. We’re changing students,” says Gill. “We’re helping to draw students to the gospel of Jesus Christ by helping them in their transition to the university and its vision.”

Planting a Flag

UNIV 101’s birth was a minor miracle, says Gill. “Nothing happens quickly in academia, and this happened in the course of a year.”

It began with a fall 2022 assignment from Church commissioner of education Elder Clark G. Gilbert (BS ’94) for each Church Educational System institution to develop a plan to instill the school’s distinctive mission and aims in its students. C. Shane Reese (BS ’94, MS ’95), then the academic vice president, pulled together his team, sketching out the rough outlines of a curriculum that combined teaching about student services with training in BYU’s distinctive mission, with efforts to build belonging along the way.

It soon became clear to the team that the heart of this course would be the BYU mission, as laid out in its founding documents and in President Spencer W. Kimball’s historic address, “The Second Century of Brigham Young University.” Could such a class help BYU students, in the prophet’s words, more fully embrace the university’s “double heritage” and become “bilingual” in study and in faith? wondered current BYU academic vice president Justin M. Collings (BA ’06).

If they could nail this mission piece, Collings felt certain that the other objectives would follow. “It’s not a course about belonging,” he explains. “It’s a course that results in a profound sense of belonging because students can unite around the mission.”

And requiring such a course for all incoming students would make a bold, unmistakable statement. “It’s a way of planting our flag,” says Collings. “It’s saying, ‘We have not, and we will not drift from our mission.’”

But how to instill this vision of BYU?

It turned out that, in an entirely independent effort, former BYU academic vice president John S. Tanner (BA ’74) had been collecting key speeches about BYU by prophets, apostles, and BYU administrators for Envisioning BYU (see speeches.byu.edu/envisioning-byu), a volume intended for BYU faculty and staff.

While meeting with John and Susan Winder Tanner (BA ’84) to learn more about the book, it only took moments for Osguthorpe to see its potential. “I think we’ve got our text,” he reported.

Topically, the class and the compendium of speeches were “a match made in heaven,” says Collings. But the team wasn’t sure whether new students would resonate with the materials, which include long talks delivered decades ago.

In hindsight, Osguthorpe calls those concerns “unwarranted.” During a recent lunch with students from a UNIV 101 class, he asked for feedback. To his surprise, a student volunteered that President Kimball’s “Education for Eternity,” one of the longest and most difficult readings, was his favorite. The speech and ensuing class discussion had persuaded the student that he wasn’t at BYU merely to prepare for a job. “This is for eternity,” he said. “It’s changed the way I look at every class I’m in.”

After watching students engage with these concepts in two sections of the class, Osguthorpe is confident that the university will achieve President Reese’s goal to Become BYU. “It’s because of the students,” Osguthorpe says. “They’ll lead the way.”

The Integrated Life

Alyson L. West (’29) admits to being starstruck when she sat down in a Maeser Building lecture hall for the first day of UNIV 101 in January. Her teachers? President Reese, advancement vice president Keith P. Vorkink (BS ’94), and Osguthorpe.

But any intimidation soon melted away, as longtime friends Reese and Vorkink swapped stories and ribbed each other. Offering insights into their own transitions to BYU—their worries and mishaps, growth and triumphs—the teachers quickly put West at ease. Clearly, they hadn’t forgotten what it was like.

West’s classmate Jeremiah P. Pauni (’28) ate up the professors’ stories of learning to integrate the worlds of academia and spirituality. Like when President Reese spoke of an epic Testing Center struggle with a particularly difficult stats exam question. After wrestling with the problem for hours, he finally turned to prayer. A flash of inspiration lit the way to an answer.

“It’s awesome,” says Pauni, “integrating the spiritual and the secular.”

Although UNIV 101 readings and class discussions tend toward matters of faith, Collings insists it isn’t a religion course, taught only by religion faculty. Involving a broad array of faculty—biologists, sociologists, engineers, fine artists—helps make the point, he says. “This is a course about how we integrate our spiritual education with our secular education and how we come to live an integrated life as a disciple scholar.”

Rick Gill says they intentionally tapped only experienced faculty. “While all our faculty are committed to a scholarly vision blending faith and reason, our more senior faculty can draw on a deep reservoir of personal experience to illustrate disciple scholarship.”

It’s delivering on the university’s distinctive value proposition, says Gill: “If you want to show what is truly unique about BYU, get a professor who is actively doing creative works or research who is fully immersed in their scholarship as a disciple of Jesus Christ.”

If the primary goal is to provide a model of discipleship for students, Gill says a close second is inviting faculty themselves to more fully engage with the prophetically laid foundation of BYU.

He says it’s having an impact. “I’m getting stopped on campus by faculty members who are saying, ‘This is changing the way I’m seeing the university.’”

Going Big by Going Small

Jeremiah Pauni didn’t initially apply to BYU. As a first-generation student, he didn’t know how he’d fit in.

A spiritual prompting during his mission led him to consider applying. But Pauni still had his doubts, which lingered when he arrived on campus. Was this a place where he could truly belong?

Pauni wasn’t alone in feeling alone. In fact, part of the impetus for UNIV 101 was to help address “the loneliness epidemic” afflicting huge swaths of college-age students today.

Collings calls loneliness an ironic problem on a 35,000-student campus. “You’d think the problem would be that you can never be alone,” he says. And yet, despite busy sidewalks and devices abuzz with social chatter, many students today feel more disconnected than ever.

And so, hoping to foster community, the UNIV 101 developers initially proposed what felt like ambitiously small section sizes for a GE class—50 students in contrast to American Heritage’s 800. But, after receiving feedback from the college deans, they trimmed the headcount to 32 and then again to just 25. If you really want to foster connection and belonging, the deans argued, the classes needed to be intimate.

“It’s not a course about belonging. It’s a course that results in a profound sense of belonging because students can unite around the mission.”

—Justin Collings

A shrinking class size meant a swelling need for classrooms and faculty—with nearly 300 professors adding UNIV 101 to their teaching load this fall.

“This is a huge investment to make as a university,” says Collings. But it’s one that’s already paying off.

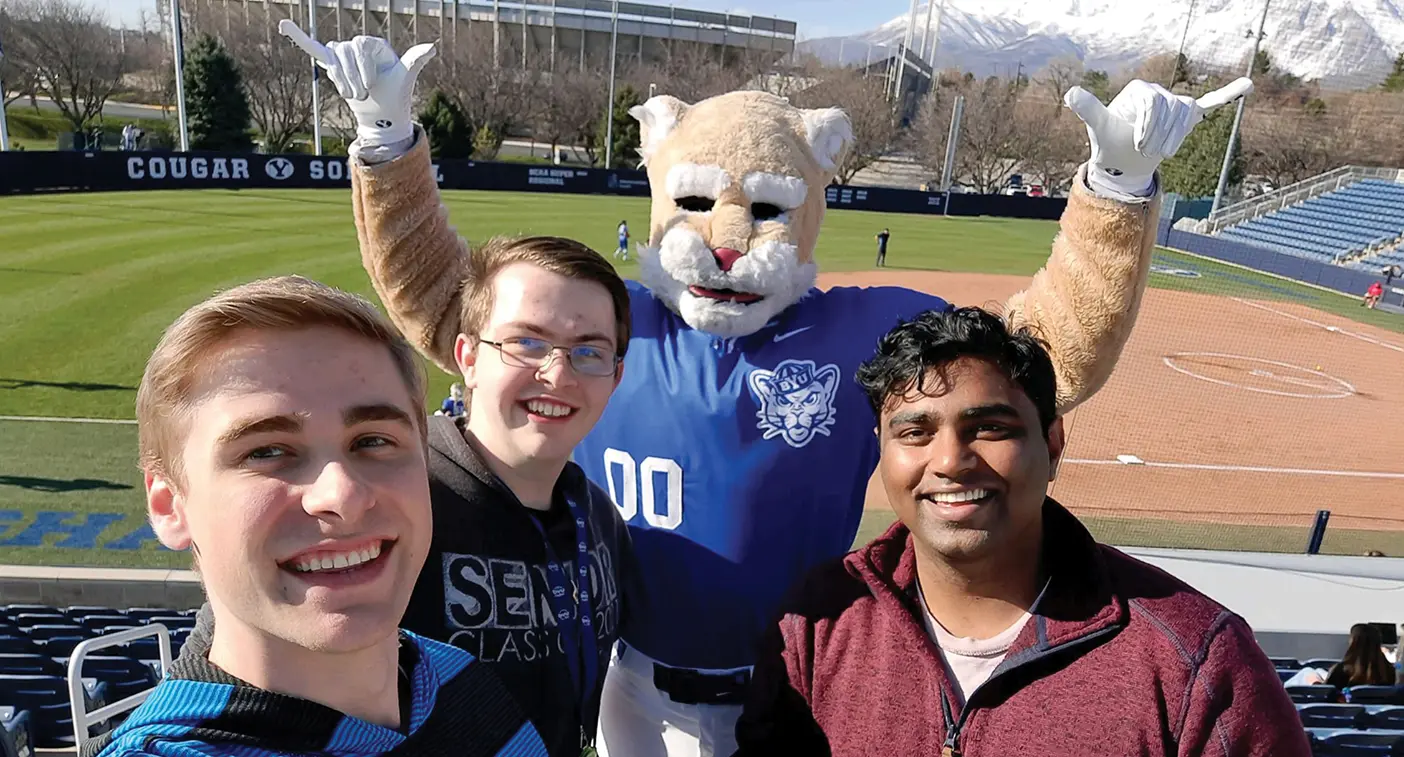

Pauni has felt the difference. “I’ve been in a bunch of big classes, and I feel like just another number,” he says. “But being in a small class, all the students felt like a family and the teacher knew us by name. I felt known.”

That feeling is cultivated by a series of assignments to experience BYU together. In small groups, class members arrange to attend devotionals, sporting events, exhibits, and musical performances. And they connect with an assigned peer mentor and directly with their professor, meeting up for lunch or dropping by during office hours to get advice.

“One of the strongest indicators of student success is [having] a connection with a professor,” says Osguthorpe. “For the first time, every single student will have a . . . relationship with a professor. You can’t avoid it in this class.”

Reese knew they were onto something one morning when a student didn’t show for class. Wondering out loud if someone should check in on him, he discovered that six students had already texted the student to make sure he was okay.

Osguthorpe saw success in a traffic jam. Hustling to get to a meeting across campus, he found his path totally impeded by a huddle of students. Frustration turned to elation when he discovered they were UNIV 101 students, lingering after class. “They didn’t want to leave.”

“Being in a small class, all the students felt like a family and the teacher knew us by name. I felt known.”

—Jeremiah Pauni

This doesn’t just come from class sizes and group activities, says Osguthorpe. The doctrine of belonging is intimately woven into class readings. “This is about covenant belonging,” he says. It’s about students understanding that they are “part of a university with a prophetic vision. . . . This is about understanding who we are as BYU and then charting a course together.”

West agrees. “We’d have fun, we’d joke around, but we’d also have amazing conversations about what we read.”

With new friends and a budding conviction about BYU’s mission, Pauni says the clincher was his UNIV 101 final project. He decided to ask a sampling of minority and other students two questions: Why BYU? and Do you feel you belong?

“I was stunned by all of the positive answers that other students gave me,” he says. “It really changed my view of BYU.”

And he finished the class with added purpose—to help change perceptions of BYU by representing God and ensuring that everyone feels they belong.

Firming the Foundation

“Our expectations were so high—maybe too high,” Osguthorpe says of the launch of UNIV 101. “But [the response] has far exceeded those expectations. The students have taken the class to a completely different level—the relationships they formed with each other, the depth with which they understand the prophetic vision of the university.”

Even more surprising may be the impact UNIV 101 is having on faculty and administrators. With several members of the President’s Council teaching classes, it’s become the norm for Reese and others to share student anecdotes, often from that very morning’s class.

“It’s ensuring that every decision that is being made at the highest levels of the university is student centered,” says Gill.

Gill says that Reese consistently points to this effort as key to becoming the BYU of prophesy. There will be many more steps ahead, he notes, but this is where it begins.

Feedback Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.