The Glorious Cause of America

The Glorious Cause of America

How a coarse, untrained army—“rabble in arms”—stood up to the world’s most powerful army.

By David McCullough in the Winter 2006 Issue

EDITOR’S NOTE: “If nations appointed historians laureate, David McCullough would surely be ours,” said Edwin Yoder, a professor of journalism and humanities at Washington and Lee University. Author of such historical works as The Johnstown Flood, The Great Bridge, The Path Between the Seas, Mornings on Horseback, Truman, John Adams, and, most recently, 1776, McCullough is a two-time winner of both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. For many years he was host of PBS’s American Experience. Like many of his heroes from history, McCullough is someone who has never stopped reading—his literary diet ranging from histories to classic fiction to children’s books to detective stories. An ardent traveler, a gifted speaker, and an avid landscape painter, McCullough is, above all, a devoted learner and teacher.

Without notes, on Sept. 27, 2005, McCullough addressed a large Marriott Center audience; the following is a condensed version of his forum address. Accompanying the text are McCullough’s combined responses to questions from a Q&A after the forum and from a separate interview by BYU Magazine.

One of the hardest, and I think the most important, realities of history to convey to students or readers of books or viewers of television documentaries is that nothing ever had to happen the way it happened. Any great past event could have gone off in any number of different directions for any number of different reasons. We should understand that history was never on a track. It was never preordained that it would turn out as it did.

Very often we are taught history as if it were predetermined, and if that way of teaching begins early enough and is sustained through our education, we begin to think that it had to have happened as it did. We think that there had to have been a Revolutionary War, that there had to have been a Declaration of Independence, that there had to have been a Constitution, but never was that so. In history, chance plays a part again and again. Character counts over and over. Personality is often the determining factor in why things turn out the way they do.

Furthermore, nobody ever lived in the past. Jefferson, Adams, George Washington—they didn’t walk around saying, “Isn’t this fascinating living in the past? Aren’t we picturesque in our funny clothes?” They were living in the present, just as we do. The great difference is that it was their present, not ours. And just as we don’t know how things are going to turn out, they didn’t either.

We can know about the years that preceded us and about the people who preceded us. And if we love our country—if we love the blessings of a society that welcomes free speech, freedom of religion, and, most important of all, freedom to think for ourselves—then surely we ought to know how it came to be. Who was responsible? What did they do? How much did they contribute? How much did they suffer?

Abigail Adams, writing one of her many letters to her husband, John, who was off in Philadelphia working to put the Declaration of Independence through Congress, wrote, “Posterity who are to reap the blessings, will scarcely be able to conceive the hardships and sufferings of their ancestors.”1 Alas, she was right. We do not conceive what they went through.

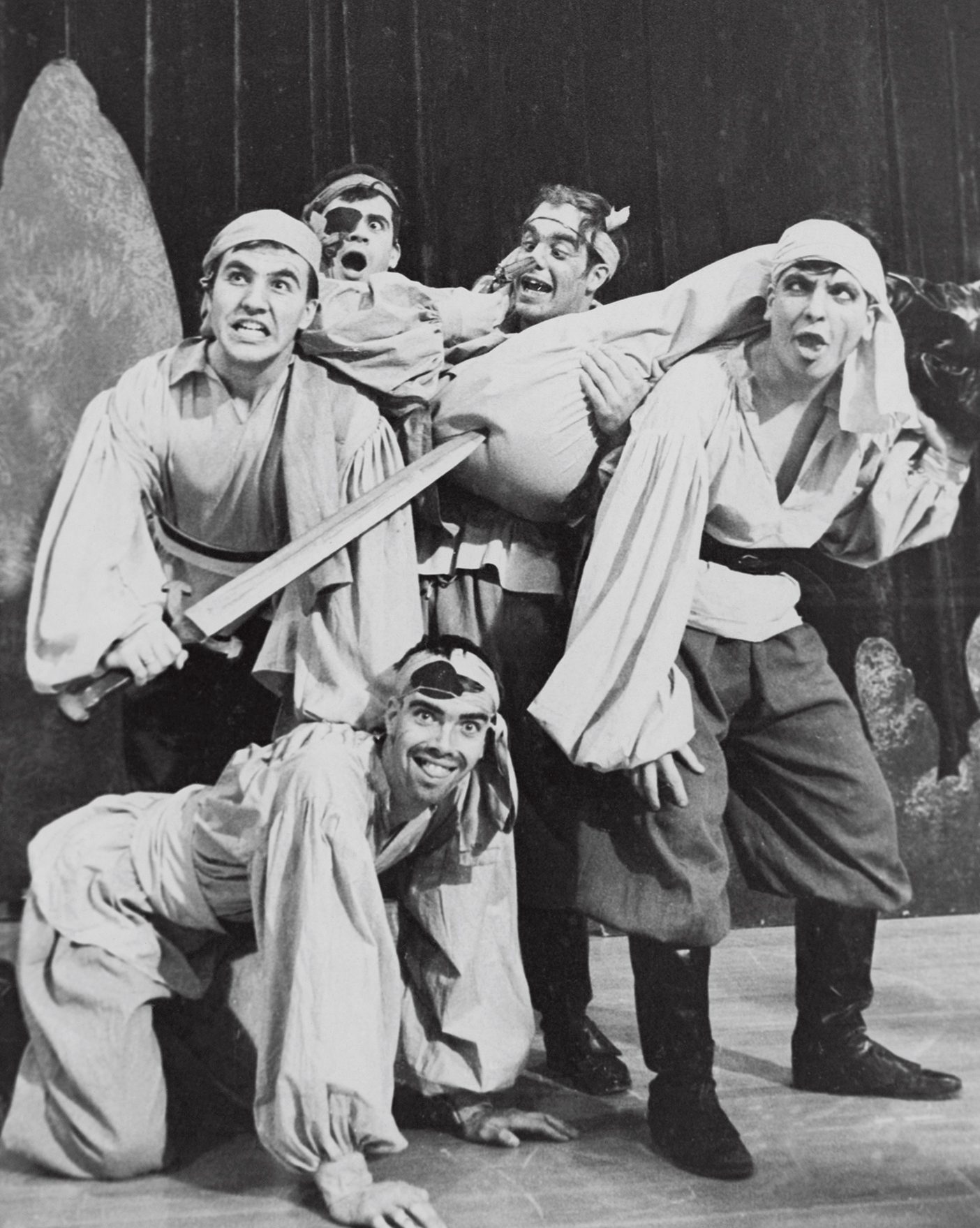

We tend to see them—Adams, Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Benjamin Rush, George Washington—as figures in a costume pageant; that is often the way they’re portrayed. And we tend to see them as much older than they were because we’re seeing them in the portraits by Gilbert Stuart and others when they were truly the Founding Fathers—when they were president or chief justice of the Supreme Court and their hair, if it hadn’t turned white, was powdered white. We see the awkward teeth. We see the elder statesmen.

At the time of the Revolution, they were all young. It was a young man’s–young woman’s cause. George Washington took command of the Continental Army in the summer of 1775 at the age of 43. He was the oldest of them. Adams was 40. Jefferson was all of 33 when he wrote the Declaration of Independence. Benjamin Rush—who was the leader of the antislavery movement at the time, who introduced the elective system into higher education in this country, who was the first to urge the humane treatment of patients in mental hospitals—was 30 years old when he signed the Declaration of Independence. Furthermore, none of them had any prior experience in revolutions; they weren’t experienced revolutionaries who’d come in to take part in this biggest of all events. They were winging it. They were improvising.

George Washington had never commanded an army in battle before. He’d served with some distinction in the French and Indian War with the colonial troops who were fighting with the British Army, but he’d never commanded an army in battle before. And he’d never commanded a siege, which is what he took charge of at Boston, where the rebel troops—the “rabble in arms”2 as the British called them—had the British penned in inside Boston.

Washington wasn’t chosen by his fellow members of the Continental Congress because he was a great military leader. He was chosen because they knew him; they knew the kind of man he was; they knew his character, his integrity.

George Washington is the first of our political generals—a very important point about Washington. And we’ve been very lucky in our political generals. By political generals, I don’t mean to suggest that is a derogatory or dismissive term. They are political in the sense that they understand how the system works, that they, as commander in chief, are not the boss. Washington reported to Congress. And no matter how difficult it was, how frustrating it was, how maddening it could be for Washington to get Congress to do what so obviously needed to be done to sustain his part in the fight, he never lost patience with them. He always played by the rule.

Washington was not, as were Adams, Jefferson, Franklin, and Hamilton, a learned man. He was not an intellectual. Nor was he a powerful speaker like his fellow Virginian Patrick Henry. What Washington was, above all, was a leader. He was a man people would follow. And as events would prove, he was a man whom some—a few—would follow through hell.

Don’t get the idea that all of those who marched off to serve under Washington were heroes. They deserted the army by the hundreds, by the thousands as time went on. When their enlistments came up, they would up and go home just as readily as can be, feeling they had served sufficiently and they needed to be back home to support their families, who in many cases were suffering tremendously for lack of income or even food. But those who stayed with him stayed because they would not abandon this good man, as some of them said.

What Washington had, it seems to me, is phenomenal courage—physical courage and moral courage. He had high intelligence; if he was not an intellectual or an educated man, he was very intelligent. He was a quick learner—and a quick learner from his mistakes. He made dreadful mistakes, particularly in the year 1776. They were almost inexcusable, inexplicable mistakes, but he always learned from them. And he never forgot what the fight was about—“the glorious cause of America,” as they called it. Washington would not give up; he would not quit.

When he took command of the Continental Army at Cambridge in the summer of 1775, Washington had probably 14,000 troops. And from those troops and from the officers who were there at the time when he arrived, he selected two men as the best he had. Here is another aspect of his leadership that must not be overlooked or underestimated: Washington was a great judge of other people’s ability and capacity to stay where the fighting was the toughest and to never give up. He picked out Nathanael Greene and Henry Knox.

Nathanael Greene was a Quaker with a limp from a childhood injury. He knew no more of the military than what he had read in books, and he was made a major general at 33 years of age. Henry Knox was 25. He was a Boston bookseller. He was a big, fat, garrulous, keenly intelligent man who, like Greene, had only about the equivalent of a fifth-grade education but had never stopped reading. He, too, knew of the military only what he had read in books. But keep in mind that this was occurring in the 18th century, their present. It was the Age of Enlightenment, an era when it was widely understood that if you wanted to know something, a good way to learn was to read books—a very radical idea to many in our day and age.

Those two men were quintessential New Englanders. Greene was from Rhode Island and Knox had grown up in Boston. Washington had discovered very soon after arriving in New England that he ardently disliked New Englanders, so to single out these two, he also overcame a personal bias.

To skip far ahead, let me point out that Nathanael Greene and Henry Knox, along with Washington, were to be the only general officers in the Revolutionary War who stayed until the very end. So Washington’s judgment could not have been better. Nathanael Greene turned out to be the best general we had, and I’m including Washington in that lineup—Greene, the Quaker with a limp, the man who knew nothing but what he had read in books, who, like Washington, learned from his mistakes.

Let’s not forget what a war it was—eight and a half years, the longest war in our history, except for Vietnam. Twenty-five thousand Americans were killed. That doesn’t sound like very much to those of us who have been bludgeoned, who have been numbed by the horrible statistics of war in the 20th or 21st centuries. This was 1 percent of the American population of 2.5 million. It was a lot. If we were to fight for our independence today and the war were equally costly, there would be more than 3 million of us killed. It was a long, bloody, costly war.

And as it wore on in the year 1776, we suffered one defeat after another. At Brooklyn—a huge battle over an area of six miles with 40,000 soldiers involved—we were soundly defeated. We were made to look foolish. We were outsmarted, outflanked, outgeneraled, outnumbered. Some of us were immensely heroic, but we never had a chance.

But then, in a miraculous escape from Brooklyn Heights on the night of Oct. 29, we got back across the East River and were saved. It was the Dunkirk of the Revolution. If the wind had been in the other direction that night or the two or three nights preceding it, there’s not much question that the war would have been over then because Washington and 9,000 American troops would have been captured. If the British had been able to bring their warships up into the East River, between Brooklyn and Manhattan, they would have had us right in the trap. But because there was a howling storm out of the northeast, they weren’t able to do that.

Washington ordered that every possible small craft be rounded up and be made ready to bring the army back to New York. It was to be done at night. An organized retreat for an experienced army is the most difficult maneuver of all when faced by a superior force. But for this amateur pick-up team, this rude, crude, un-uniformed, undisciplined, untrained American army of farm boys—some of whom had been given a musket and told to march off only a few weeks before—for that kind of an army to make a successful retreat across water at night, right in the face of the enemy without the enemy knowing, was a virtual impossibility. And yet they did it.

When they went down to the shores of the East River, right where the Brooklyn Bridge now stands, to start the crossing, the same wind that was keeping the British from bringing their fleet up was keeping the river too rough for them to make the crossing. It looked as though they weren’t going to be able to pull it off. Then, all of a sudden, almost like the parting of the waters, the wind stopped. The makeshift armada started going back and forth, back and forth, all night long, ferrying men, horses, cannon—everything—back across the river to New York. And they succeeded. Nineteen thousand men and all their equipment—horses, cannon, and the rest—were taken across the river that night without the loss of a single man and without the British ever knowing it.

I wanted to write about that event, the reality of what happened there, as much as anything else in my book 1776. It shows so much that we need to understand. First of all, it was said right away that the hand of God had intervened in behalf of the American cause. Others trying to interpret what had happened used the words providence or chance. But it couldn’t have happened only because of chance or the hand of God. It also required people of skill and experience with the nerve to try it.

That escape was organized and led by a man named John Glover from Marblehead, Mass., and his Marblehead Mariners—fishermen, sailors who knew how to handle small boats. During the crossing—and the East River can be a treacherous place to cross, even in the best of conditions—boats were loaded down so that the gunwales were only a few inches above the water. No running lights, no motors, no cell phones to talk back and forth. And they did it. It was character and circumstance in combination that succeeded.

The men were totally demoralized. They had been defeated; they were soaking wet; they were cold; they were hungry. They lost again pathetically at Kip’s Bay. They lost again in the great battle of Fort Washington, when nearly 3,000 of our troops and all of their equipment were taken captive.

By the time Washington started his long retreat across New Jersey, they were down to only a few thousand men. Probably a quarter of the army were too sick to fight, victims of smallpox, typhoid, typhus, and, worst of all, camp fever, or epidemic dysentery. Men deserted, men defected—went over to the enemy by the hundreds. Or they just disappeared, they just went away, never heard from again. By the time Washington was halfway across New Jersey, he had all of 3,000 men.

We are taught to honor and celebrate those great men who wrote and voted for the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia. But none of what they committed themselves to—their lives, their fortunes, their sacred honor—none of those noble words about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, about all men being created equal, none of that would have been worth any more than the paper it was written on had it not been for those who were fighting to make it happen. We must remember them, too, and especially those who seem nameless: Jabez Fitch and Joseph Hodgkins; little John Greenwood, who was all of 16 years old; and Israel Trask, who was 10 years old. There were boys marching with the troops as fifers or drummers or messenger boys, not just Nathanael Greene and Henry Knox and John Glover and George Washington. And they were in rags—they were in worse than rags. The troops had no winter clothing. The stories of men leaving bloody footprints in the snow are true—that’s not mythology.

Washington was trying to get his army across the Delaware River, to put the river between his army and the oncoming British army, which was very well equipped, very well fed, very well trained—the best troops in the world led by an extremely able officer, Cornwallis. On they were coming, and they were going to end the war. But Washington felt that if he could just get across the river, get what men he had left over on the Pennsylvania shore on the western side, destroy any boats the British might use to come chasing across the river, that they’d have time to collect themselves and maybe get some extra support. Again they went across at night. Again it was John Glover and his men who made it happen. They lit huge bonfires on the Pennsylvania side of the river to light the crossing.

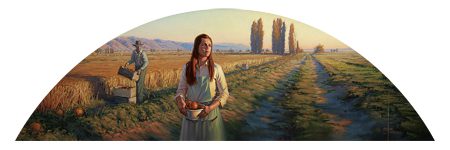

The next morning a unit from Pennsylvania rode in—militiamen, among whom was a young officer named Charles Willson Peale, the famous painter. He walked among these ragged troops of Washington’s who had made the escape across from New Jersey and wrote about it in his diary. He said he’d never seen such miserable human beings in all his life—starving, exhausted, filthy. One man in particular he thought was just the most wretched human being he had ever laid eyes on. He described how the man’s hair was all matted and how it hung down over his shoulders. The man was naked except for what they called a blanket coat. His feet were wrapped in rags, his face all covered with sores from sickness. Peale was studying him when, all of a sudden, he realized that the man was his own brother.

I think we should feel that they were all our brothers, those brave 3,000, and remember what they went through, just as Abigail Adams stressed in her letter. And that they didn’t quit!

Washington took stock, just as the British army was taking stock, of the situation, as were most every officer and all of the politicians, many of whom had fled from Philadelphia by this time. It seemed clear that the British were heading for Philadelphia and there was nothing to stop them. Most everybody concluded that the war was over and we had lost. It was the only rational conclusion one could come to. There wasn’t a chance. So Washington did what you sometimes have to do when everything is lost and all hope is gone. He attacked.

They went up the river nine miles to McKonkey’s Ferry on Christmas night. They crossed the Delaware, famously portrayed in the great painting Washington Crossing the Delaware, which as everyone knows is inaccurate in many ways. But it does portray with drama and force what was one of the most important turning points, not just in the history of the war, but in the history of our country and, consequently, of the world. He had the nerve, the courage, the faith in the cause to carry the war once more to the enemy. After the crossing, they marched nine miles back down the river on the eastern side and struck at Trenton the next morning.

The worst part of the whole night was not the crossing, as bad as it was. The worst part was the march through the night. Again a northeaster was blowing, and again that northeaster was beneficial to our cause because it muffled the noise of the crossing and the noise of the march south. But it also increased by geometric proportions the misery of the troops. It was very cold. What the wind chill factor must have been can only be imagined. It was so cold that two men froze to death on the march because they had no winter clothing.

They struck at Trenton the next morning. It was a fierce, house-to-house, savage battle. It was small in scale but very severe. It was all over in about 45 minutes, and we won. For the first time, we defeated the enemy at their own profession.

Now it wasn’t a great battle like Brooklyn. But its consequences were enormous, beyond reckoning. Because of the psychological effect, it transformed the attitude of the army and of much of the country toward the war. It was a turning point. They struck again at Princeton a few days later and won there too—again by surprise, again after marching through the night, again taking the most daring possible route, risking all and winning.

In conclusion I want to share a scene that took place on the last day of the year of 1776, Dec. 31. All the enlistments for the entire army were up. Every soldier, because of the system at the time, was free to go home as of the first day of January 1777. Washington called a large part of the troops out into formation. He appeared in front of these ragged men on his horse, and he urged them to reenlist. He said that if they would sign up for another six months, he’d give them a bonus of 10 dollars. It was an enormous amount then because that’s about what they were being paid for a month—if and when they could get paid. These were men who were desperate for pay of any kind. Their families were starving.

The drums rolled, and he asked those who would stay on to step forward. The drums kept rolling, and nobody stepped forward. Washington turned and rode away from them. Then he stopped, and he turned back and rode up to them again. This is what we know he said:

My brave fellows, you have done all I asked you to do, and more than could be reasonably expected, but your country is at stake, your wives, your houses, and all that you hold dear. You have worn yourselves out with fatigues and hardships, but we know not how to spare you. If you will consent to stay one month longer, you will render that service to the cause of liberty, and to your country, which you can probably never do under any other circumstance.3

Again the drums rolled. This time the men began stepping forward. “God Almighty,” wrote Nathanael Greene, “inclined their hearts to listen to the proposal and they engaged anew.”4

Now that is an amazing scene, to say the least, and it’s real. This wasn’t some contrivance of a screenwriter. However, I believe there is something very familiar about what Washington said to those troops. It was as if he was saying, “You are fortunate. You have a chance to serve your country in a way that nobody else is going to be able to, and everybody else is going to be jealous of you, and you will count this the most important decision and the most valuable service of your lives.” Now doesn’t that have a familiar ring? Isn’t it very like the speech of Henry V in Shakespeare’s play Henry V: “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers . . . And gentlemen in England now a-bed / Shall think themselves accursed they were not here”?5 Washington loved the theater; Washington loved Shakespeare. I can’t help but feel that he was greatly influenced.

He was also greatly influenced, as they all were, by the classical ideals of the Romans and the Greeks. The history they read was the history of Greece and Rome. And while Washington and Knox and Greene, not being educated men, didn’t read Greek and Latin as Adams and Jefferson did, they knew the play Cato, and they knew about Cincinnatus. They knew that Cincinnatus had stepped forward to save his country in its hour of peril and then, after the war was over, returned to the farm. Washington, the political general, had never forgotten that Congress was boss. When the war was at last over, Washington, in one of the most important events in our entire history, turned back his command to Congress—a scene portrayed in a magnificent painting by John Trumbull that hangs in the rotunda of our national Capitol. When George III heard that George Washington might do this, he said that “if he does, he will be the greatest man in the world.”

So what does this tell us? That the original decision of the Continental Congress was the wise one. They knew the man, they knew his character, and he lived up to his reputation.

I hope very much that those of you who are studying history here will pursue it avidly, with diligence, with attention. I hope you do this not just because it will make you a better citizen, and it will; not just because you will learn a great deal about human nature and about cause and effect in your own lives, as well as the life of the nation, which you will; but as a source of strength, as an example of how to conduct yourself in difficult times—and we live in very difficult times, very uncertain times. But I hope you also find history to be a source of pleasure. Read history for pleasure as you would read a great novel or poetry or go to see a great play.

And I hope when you read about the American Revolution and the reality of those people that you will never think of them again as just figures in a costume pageant or as gods. They were not perfect; they were imperfect—that’s what’s so miraculous. They rose to the occasion as very few generations ever have.

NOTES:1. Abigail Adams to John Adams, March 8, 1777, Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston; spelling modernized.2. John Burgoyne, in Sir George Otto Trevelyan, The American Revolution (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1926), vol. 1, p. 298.3. Sergeant R——, “Battle of Princeton,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 20 (1896), pp. 515–16.4. Nathanael Greene to Nicholas Cooke, Jan. 10, 1777, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, ed. Richard K. Showman and Dennis Conrad (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980), vol. 2, p. 4.5. Henry V 4.3.63–68.FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

Q&A with David McCullough

ON HISTORY AND WRITING

Q: How did you become a historian?

McCullough: Like a lot of things in life, I backed into it, quite by chance. I was working on a project for the U.S. Information Agency in the 1960s. I was often at the Library of Congress doing research. One Saturday, I came across some photographs taken in Johnstown, Pa., soon after the disastrous flood of 1889. I had grown up in Pittsburgh, which is not very far from Johnstown. I’d heard about the Johnstown Flood during my childhood but never really understood what happened. When I saw the level of destruction in those pictures, I was curious to know more about what happened. I took a book out of the library to read about it, and it wasn’t much good. The author didn’t seem to understand the geography of western Pennsylvania. I at least knew that. So I took another book out and found it even less satisfactory. I began to think, “Why don’t you try to write the book about the Johnstown Flood you’d like to read?” So that’s what I did. I was about 29 at the time. I’d never done historical research. So I had a lot to learn, but I had found what I wanted to do with my life.

Q: Does “writing the book you would like to read” guide your writing approach in general?

McCullough: Yes. I write for the general reader. I hope that the aficionados, the scholars, the specialists will like what I write, but I also hope that the fellow who lives next door will like what I write, that somebody of 17 and somebody of 87 will enjoy it. I’m just trying to write the best book I know how. Obviously, I care very much about accuracy and the validity of the tale, getting it right. And I love the research. But the writing is what I care about the most.

Q: You have said that in your research process you try to feel what it was like to live in the given time. How do you that?

McCullough: By reading what they wrote, their letters, their diaries. By reading what they read—that’s very important. By literally walking the walk, visiting the site, spending the night where they were, soaking it up in every way possible. By looking at their clothes, looking at the houses they lived in. By trying to understand what getting through a winter in a house that had nothing but a fireplace for heat was like. By experiencing what it is like to swing a pick or a shovel in the heat of Panama in the rainy season or going into the jungle at night without a flashlight.

Q: How do you choose a subject to write on?

McCullough: It’s a peculiar thing, and I can’t really pin it down, but it can be something someone says at a lunch, which was the case in my book about the Brooklyn Bridge. It can be something that I said, not realizing that I was saying it. When I was talking with my editor about what my next book would be, he suggested a biography of Franklin Roosevelt. And I said no, I didn’t want to do Franklin Roosevelt. If I were ever to do a 20th-century president, it wouldn’t be FDR, I said, it would be Harry Truman. I’d never before thought for five minutes about that. I don’t know why I said it. It just came out.

Sometimes the subject derives from my previous book. The Path Between the Seas, my book about the Panama Canal, was an idea that my editor had. And from writing it, I’d become quite interested in Theodore Roosevelt and particularly his childhood. So that led to Mornings on Horseback. The book 1776 comes out of the experience of writing the Adams biography, as I was very aware of how much was going on of importance—vast importance—that Adams was playing no part in, namely the war itself.

I’ve never written a book because I thought there would be a market for it or because there was going to be an anniversary celebrated three years hence. You can’t predict interest.

I think you have to do what you really want to do, what compels you, because you’ve got to get up your own head of steam every day and get out there and work. And if it isn’t something you really want to do, if it just becomes an obligation, a routine, it’s not likely to be very good. It will show that you’re just going through the motions.

Q: What do you think about present-day academic history?

McCullough: I think there are some marvelous historians today working in traditional academic history—David Hackett Fisher, Gordon Wood, James McPherson, John Lukacs. They are superb historians and very good writers. And there are others, of course.

What worries me are the historians who are writing only for other historians and who don’t seem to care at all about whether they’re writing anything that anyone besides other historians would want to read. I really do believe that if history isn’t written to be read—if those who write history don’t at least aspire to writing literature as others have done, beginning with Homer and Thucydides—then history will die. Nobody will want to read it.

I do what I do in my way as best I can. I write narrative history. And I love to read narrative history. People say to me, “Your books read like a novel.” Well, that’s exactly how I want them to read. For years I read historical novels. I loved them. But always there was the nagging thought, “How much of this is true and how much isn’t?” And “Wouldn’t it be wonderful to read a book where it was all true but it read like this?” And that’s what I have tried to do.

Q: Who are your heroes from history after doing the research you’ve done?

McCullough: Oh, Abigail Adams, John Adams, Emily Roebling, Washington Roebling, George Washington, John Stevens—the American engineer who worked on the Panama Canal.

But sometimes the heroes aren’t necessarily the ones you’d most like to write about. I loved writing about Boss Tweed, and he’s certainly not a hero. I loved writing about some of the less-than-virtuous people in the Truman years. I like vivid characters, I love people who speak their mind, who leave us some trace of their personality and individual identity.

Q: You have said we should use history as a source of hope and strength in the hard times of our lives. Which story from history has served you as a source of strength and hope?

McCullough: Because I’ve been so close to them the last 10 years or more, I would say the story of the Adams family and the whole Revolutionary War era.

I’ve found tremendous inspiration in the story of the Roebling family and the building of the Brooklyn Bridge and all that it took to make that possible. I think the Brooklyn Bridge is a great symbol of affirmation, a symbol of Americans struggling against the odds to do something unprecedented and surpassing, something that, in fact, turned out to be a great American symbol, a great work of art.

Q: What do you think are some of the most pressing problems facing our nation today, and as a historian, do you see any lessons or solutions from the past that could be applied?

McCullough: I think the most pressing problem we face today is lack of self-confidence and pride in who we are and what we’ve done and what we have the capacity to do. And I think if we lose our self-respect and our trust in our neighbor and our faith in what we stand for, we’re really in the soup. We’re up against a foe who believes in enforced ignorance. And we don’t. We have to hold to our beliefs and our trust in who we are and not allow circumstances to vitiate our better natures.

I think we face very serious environmental problems. I think we face very serious problems of how to be competitive and maintain anything like the standard of living we have enjoyed in a world that is fast learning how to do so much that we do.

Q: Are there other lessons you have taken from your study of history?

McCullough: One is that there was no “simpler time.” People will say, “Well, that was in a simpler time. That was back before life got complicated.” There wasn’t any simpler time. It was just different. And I think that comes through in any close study of how people lived and the fears and the hardships and the uncertainties that they had to live with every day—disease, the hazards of occupations, all of that.

We’re softies compared to people from past centuries. We truly are. We have no idea the discomforts and the inconveniences they knew. Life beat them up a lot, and it showed on their faces—missing teeth, scars, casts in the eye. John Trumbull the painter had the use of only one eye as the result of a childhood injury, but that didn’t stop him from being a painter. Imagine. Imagine going to an 18th-century dentist. Imagine what it was like for Abigail Adams the second, Nabby, as she was called, having a mastectomy performed with no anesthetic. Unimaginable. Think of what it was like for her parents standing outside that room, knowing what she was going through. Unimaginable.

That is one of the lessons that ought to be conveyed in understanding American history. We are all descendants of people who went through rough times—for us. I think that there is an overemphasis on how dangerous and dark and bleak and critical our own times are. After Sept. 11 we heard people on television saying this is the darkest time we have ever been through. Anyone who thinks that has no sense of history, because we have been through worse times. We were through worse times in 1776. We were through worse times during the Civil War. We were through worse times in the Depression. The first few months of 1942 were about as dark a time for the world as there ever was. There was no guarantee that the Nazi machine could be defeated, none whatsoever. Half our navy had been destroyed at Pearl Harbor. We had recruits drilling with wooden rifles. We had virtually no air force. The Germans were sinking our oil tankers right off the coast of New Jersey and Florida within the sight of the beaches—and there was nothing we could do about it. That was a dark time. And in the midst of that dark time, Winston Churchill came across the Atlantic and gave a very powerful speech in which he said, “We haven’t journeyed this far because we are made of sugar candy.”

I think another lesson we should draw from history in general is that there is no such thing as a self-made man or woman. We’re all the products of a multitude of influences—other people, teachers, parents, friends who’ve helped us or badgered us or reprimanded us when we didn’t do it right; people who have been our rivals or our competitors; people who have given us inspiration, new ideas, called on us to do something more than we thought we could do; and people we never knew because they lived long ago in another day. We’re beholden to them more than we know. They’ve shaped us. I love to point out to people how we walk around every day, all of us, quoting Shakespeare, Pope, Cervantes, Swift and not even realizing it. The very words we speak we owe to other people.

Certainly another lesson is that democracy doesn’t come easily. You don’t just find it on the road and pick it up and put it in your pocket. It doesn’t just drop off some kind of a democracy tree. It’s a struggle, often a long, bloody, costly struggle.

One of the greatest lessons from those who went before us is to never, never, never stop learning. Until their dying days, many of them were still reading, thinking, still daring to write and speak.

Q: Do you feel that God had a hand in the Revolution?

McCullough: I feel that some force beyond our understanding entered in. Did miracles happen? Yes indeed. I think it’s a miracle that it turned out the way it did. I won’t get into a theological explanation of that. That’s personal and beyond my capacity to explain.

Q: In your books, the pictures you have painted of characters like John Adams, King George, and others have differed from traditional conceptions of them. Is your role as a historian to revise and correct our way of remembering the past?

McCullough: I think in many ways, I want to give credit where credit is due. I want to be fair and to break through some of the inadequate or inaccurate interpretations or portrayals by historians, which have just been repeated over and over and over because one historian just repeats the other. If one goes and studies all the available material, the letters, the diaries, all the primary source evidence, and comes to a different conclusion, that’s fine. What I object to is when they just continue to use the same old adjectives, the same old supposedly damning quotations and don’t bother themselves to look to see what the man really said or really did.

All history is revisionist history. It has to be. So when somebody says, “What do you think of these revisionists?” I think that’s just the way it is. If you aren’t going to revise how an event or individual is described or interpreted or analyzed, then why do it? History is never static. It never stays the same. It is taking new looks because times are changing and because new information comes to light all of the time, out of areas where you think there couldn’t possibly be anything more that isn’t already known. And then, lo and behold, things turn up.

Q: In John Adams, 1776, and other projects that you’ve been involved in, you seem to respect the bravery and courage of some of these characters. What do you make of the many modern histories that are cynical about the character of the Founding Fathers and others from the past?

McCullough: That’s what I would call the hubris of the present, the idea that we are somehow superior to them and we can therefore look down on them, even down on the best of them. I don’t like hero worship; I don’t like hagiography; I don’t like rose-colored glasses, because that isn’t the truth. All you’re trying to do, it seems to me, is make history as interesting as it really was and to give them a little benefit of the doubt. You weren’t there. You don’t know what it was like to have no sleep for three nights in a row and to march in the rain and mud all that time and be so hungry you’re ready to eat your knapsack. You don’t know what that’s like.

Q: Many of the patriots of the Revolution are lost in our current understanding of history. How can we learn more about people like the 3,000 who stayed by Washington’s side in 1776? Where are these common people’s stories registered?

McCullough: We have no photographs of them. We have no recordings of their voices. We have no film, no television outtakes. We don’t even have any reportage. No newspaper reporters covered the Revolutionary War the way reporters covered the Civil War, for example. No artist correspondents covered the Revolutionary War the way Winslow Homer covered the Civil War.

The soldiers’ stories are available in their own words. What we do have are their letters and diaries. They are in books. They are in anthologies. There is a wonderful two-volume anthology, edited by Henry Steel Commager and Richard B. Morris, called The Spirit of ‘Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants. It’s the letters and diaries from all sides, not just the American side, but British, Hessian, loyalists, and innocent bystanders. In that collection, you can then find out what the source is and whether there are larger collections of the letters of individuals.

The Revolution is a rich field, and there are wonderful libraries all over the country that have specialized in the period. You can go and read the original documents yourself—hold those letters in your own hand. And there’s nothing quite like that to bridge the gap between then and now.

To me, one of the most thrilling, almost unbelievable stories of 1776 is the successful feat pulled off by Henry Knox in bringing the guns from Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York down the Hudson River and over the Berkshire Mountains in the midst of winter, all the way to Boston, a distance of nearly 300 miles. It’s like something out of mythology, yet it really happened. In the Massachusetts Historical Society there is the original diary that Knox kept through the whole trek. If you ever go to Boston and want to see it, go to the Massachusetts Historical Library, ask them to bring it out, and look at it. It’s right there.

Our great libraries are open to all, thank goodness. If you’re serious about it, if you’re a student, a scholar, or just a citizen who really cares, they’ll be happy to show you such treasures.

ON EDUCATION AND THE ARTS

Q: Do you feel that a love for and an understanding of our country has been lost among the citizenry? If so, what can we do as a community to cultivate it?

McCullough: I don’t think it is lost, but it is eroding because we have been doing a very less-than-adequate job of educating our children in history. I think it is not exaggerating to say that we have been raising several generations of young Americans who are, by and large, historically illiterate. And it is not their fault. It is our fault. That has got to be corrected.

Q: How can we better teach history in schools today?

McCullough: We can do a better job of teaching our teachers. We shouldn’t send teachers who don’t know history into a classroom. And we need to get rid of these dreadful textbooks. Some textbooks are quite good, but there are far too many that are deadly. It’s almost as if they were written to kill any interest the student might ever have in history. I’ve taught classes at Cornell, Dartmouth, and elsewhere. I’ve never asked a student to read something I wouldn’t want to read. Nor do I think that one necessarily has to stick to history or biography. I’ve used the novel The Killer Angels in teaching a course, and I’ve used Willa Cather’s novel My Antonia. There are many superb novels that take one into that time past. That’s what you’re trying to do—get across that barrier of time between us and them. It’s possible; you can feel the reality of what happened.

I don’t think you can know something until you feel it. If you could know something without feeling it, then go look it up in the encyclopedia. But if you’re going to remember it, if it is going to become part of you, you have to have some feeling about it. And that is, of course, what the theater does, what poetry does, what some movies can do powerfully.

Q: What do you think is changing in education these days?

McCullough: Well I’m very concerned about the cutback in the arts. I think that’s a serious flaw, and we’ll pay for it eventually. I think that the abandoning of prerequisites in college education—that students who are going to major in the humanities or liberal arts don’t have to take any history, for example—is inexcusable. In some places students don’t have to take a foreign language. How flagrantly unrealistic that is. How naïve to think that we’re going to hold our place in the world with no concern about other people’s languages and understanding other people. I think that’s a very great failing in education today.

We’re not paying our teachers enough. That’s self-evident. But I think, too, we don’t give them sufficient recognition as the important people in society that they are. I think they’re our most important people. Too often people think of them as glorified babysitters taking care of our children while we go out and do the important work. Who are we kidding?

I’m very concerned that the academic-performance level of people going into teaching is getting lower. Because so many students have debts to pay—debts they have accrued because of their education—and feel they can’t afford to take a low-paying teaching job, which won’t enable able them to pay off their debts. I have a son who is a very able 20-year veteran of teaching, and I know what a struggle it’s been for him.

Q:Aside from pay, how can we help ennoble the calling of teaching?

McCullough: Well, I think corporations and hospitals and eleemosynary institutions ought to have teachers on their boards of directors so they are seen as people of consequence in the community. I think there ought to be major awards for teachers given by every town and city. I think the newspapers ought to do thoughtful profiles of good teachers and what distinguishes their particular way of teaching or what has distinguished their particular career. And don’t wait until they retire or die to write about the good they’ve done. After all, these are people who touch and influence the lives of thousands. We should raise their position and their level of respect in the community in every way possible.

Q: You’ve mentioned the importance of the arts. How do they relate to teaching history?

McCullough: If you take history and squeeze all of the flavor and color and life out of it, it’s a dead thing. It ought to be alive because that’s the way it was. It’s about life. Our musicians, our dancers, our painters are often expressing the deepest longings, the deepest worries, fears, aspirations of our own time. It’s been the same in all times. To say you’re writing history or understanding history and you’re putting all that—the art, the music—over in the department of art or department of music—that’s to look at history with blinders on. The more art and music and theater and literature that can be brought into the teaching and the enjoyment and the understanding of history, the better.

That’s why it’s so important that we keep the arts alive in our public schools, grade schools, and high schools. We’re cheating our children if we cut back or stop art programs, art classes, and music programs. In New York City there is a warehouse full of musical instruments that belong to the public school system that aren’t being used because they are not teaching music anymore. That’s disgraceful. That’s a scandal, in my view.

We ought to be teaching history by including the arts. It is one way to get closer to the humanity of the people of the other times. Imagine all those statues in Washington of past generals and politicians who stand forgotten in street circles and little parks, serving mainly as perches for pigeons. Then imagine the music of Gershwin, which is as alive and fresh and thrilling as the day it was written. The same with the paintings and the theater of other times. Here we are quoting and talking about Shakespeare centuries later. And I find that part of history extremely moving and reassuring as a source of strength. They weren’t just painters, they were living in a time and they were expressing the time they lived in. Go back and read again some of the classics of English literature that you were required to read in high school and college. The reason that they’re classics is that they are marvelous. And it is not just the quality of the writing; it is the quality of the thinking, because that is what writing is—thinking.

Q: What lessons can we learn from those you have studied regarding education?

McCullough: That it only comes through hard work. You have to really apply yourself. You have to buckle down and burn the midnight oil. And that education can indeed transform the life of an individual and thus transform the society in which the individual lives. The importance of education, the willingness to spend large sums of money, to enlist all kinds of talent, to create improved education is a powerful, prevailing theme through our whole history, from the very beginning. If you were going to pick out two or three consistent, continuing themes in American life, education is one.

Harry Truman is the only president of the 20th century who never went to college. But I would say that that was in no way indicative of how learned he was. He wasn’t an intellectual, and he wasn’t steeped in any academic discipline, but he never stopped reading. His great love was to read history. Truman was very interested in the Civil War. He was also quite serious about music. He would go to hear the National Symphony, not because it was a photo opportunity or because it was the dearest pleasure of a political backer. He went to the National Symphony because he loved it. And if they were playing somebody he was particularly fond of, Mozart, for example, he would take the score.

ON LEADERSHIP AND CITIZENSHIP

Q: What has your study of history taught you about leaders?

McCullough: That we shouldn’t expect our leaders, even the best of them, to be perfect, to be incapable of making mistakes. It’s very childlike for the whole country to get rattled because the president or the secretary of state or someone says something that’s silly or inappropriate or wrong. That’s the way it has always been. The only difference is that everything is recorded now. Everything is reported. Everything is amplified by a 24-hour media barrage.

Particularly with the modern presidency, I’m much more inclined to give presidents some slack. That’s a terrible job, a huge job. Nobody is up to it; nobody is qualified. How would you like to have to try to sleep every night knowing what a president knows or with the lives of so many people on your mind, on your conscience?

Sure, we should be critical when they do something really inappropriate or in an unfeeling or tactless way. Certainly. But we’re all in this together. And I feel very strongly that we need people who are there to help solve problems. I wish we had a Problem-Solver Party, because we have very big problems that need solving. And I think a lot of our attention is addressed to the wrong problems. To get all worked up and vicious and mean and to threaten people’s lives and reputations over issues that aren’t really of national consequence is plain foolish, shortsighted, immature.

Q: Who do you think are some of the great leaders of history?

McCullough: Leaders have come in all shapes and sizes, genders and color all along. They very rarely have been effective without using the power of the spoken or the written word. The capacity to move people with what they said was at least as outstanding as any of their other strengths. Some leaders who didn’t have that ability were less important in the long run because of it. Harry Truman was a very strong, brave, good-hearted man with an unusual gift for common sense. But he lacked the ability to move people with what he said, the way Franklin Roosevelt did. The speeches of Franklin Roosevelt, certainly Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, John Kennedy’s inaugural address, virtually everything that ever came out of the mouth of Winston Churchill are all worth close study. Nelson Mandela. People say we don’t have any great leaders any more. Of course we do. You just have to lift your eyes up beyond boundaries. And I think Jesus Christ was one of the greatest leaders of all time. Napoleon certainly was a great leader. Napoleon’s adages about life, his maxims, his understanding about human nature, his words to the wise are all quite remarkable.

These are people with a great gift. And if they’re lucky, they appear on the scene—they’re shoved on stage or force themselves on stage—at exactly the right moment. Theodore Roosevelt, I think, is a superb example of this. He was exactly the right president for that time. And while he wasn’t eloquent, his tremendous vitality and his passion came through in such a way that he truly could move people, and particularly young people. It was also important that he himself was young—the youngest president we ever had.

It is very hard to predict who is going to be a great leader. Who would have thought that Rudy Giuliani would be exactly the right man for the right moment? It was as if God had put him on the earth for that one day, that one week. You just don’t know who is going to be the right person. But the quality of leadership is always a major factor in how things turn out.

Q: Why are some presidents, like Adams, somewhat forgotten in history and others, like Jefferson, remembered?

McCullough: Many people wonder why John Adams has so been eclipsed by Thomas Jefferson and Washington. One of the reasons is that the Federalist Party died out. So it has never been advantageous to a present-day Federalist Party to celebrate its great founders—Washington, Hamilton, and Adams—at annual dinners to raise funds for the Federalist Party.

Adams was also a one-term president, and unless our one-term presidents are assassinated in office, we don’t pay them much heed in our pantheon of great Americans. One wonders why. Is it because we are so enamored with winners? Is it because we are so determined to be winners ourselves, and if someone is not reelected he becomes a loser? I don’t know. Jimmy Carter, George Bush the elder, Gerald Ford—they were all one-term presidents. Will they be taken as seriously as Ronald Reagan or Harry Truman or Franklin Roosevelt? I doubt it very much, because they were one-term presidents. It’s the same with John Adams.

Also, we have never really taken a New Englander to our hearts. John Kennedy was very popular, but remember that he was barely elected. He was also very photogenic, and he was also a martyr. All of those in combination have made him stand out, particularly in the eyes of young people. Often when I go to universities, I ask, “Who was your favorite president?” or “Who was the president you admire most?” or “Who do you think was the most important president?” Again and again they will say Kennedy. When I ask why, they are kind of stumped for an answer.

I think Kennedy’s great contribution was that he swept a whole generation of young people up with the spirit of serving their country—”Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country.” I was one of them. I had a very good job in New York. I had children to support. I had promises of advancement and so forth. I left it all behind and went off to Washington to serve in the government. It was one of the best things I ever did and one of the most exciting times of my life. And I urge all of you sometime to commit yourself to some enterprise or service in which you can do something for your country.

If I were to criticize President George W. Bush, I would say that he has not called upon us to serve sufficiently. We want to serve. We want to do something to help. We want to be useful. I think that’s one of the strongest of human desires—to feel we’re useful. I don’t think we can just continue along as though everything is just fine and not pitch in, not help. But how? That’s where leadership comes in.

Rosalee and I were in Washington at the Hay-Adams Hotel across Lafayette Park from the White House on Sept. 11. We saw it all happen. We saw the Pentagon hit, the smoke billowing up like a volcano in eruption. We saw the staff of the White House pouring across the park, coming across the street, all evacuating. We saw the looks on the faces of those people. It wasn’t a look of panic. Nobody was running. It was a look of concern. Their immediate impulse was “What can we do to help?” What could we do? We decided we could give blood. So we set off to walk to the George Washington Hospital. When we got there, they sent us back, saying, “We’ve had so many hundreds of people come to give blood, we can’t possibly handle it all.”

That desire to do something, that’s a tremendous resource. Our leaders should call upon us to do more.