On a mid-March afternoon in Jerusalem, there is not a cloud in the sky. Birds twitter incessantly, their songs overlapping and responding to one another, from tree to tree along the terraces of BYU’s Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies. The chipped limestone of the walls and pavement is bright enough to make you squint. On every terrace, recently pruned rosebushes are leafing out in soil fed by the black lines of drip irrigation hoses. The sun casts sharp shadows behind white plastic chairs and cedar posts. From the street below, you hear the strident horns of passing traffic. Sometimes children’s voices rise from the property just east of the center, where local Palestinians have made a dirt soccer field.

Every student apartment in the Jerusalem Center has a terrace balcony that faces southwest toward the Old City. In good weather students come out to read scriptures, to write in their journals, to hear the calls to prayer or the church bells that ring at certain hours, to watch the sun rise or set. At sunset the city seems to hold the  golden haze of last light as long as possible before fading to a silhouette on the western skyline. “I really enjoy watching the sun set over Jerusalem every night,” says Justin B. Top, a BYU student who spent winter semester 1999 in Jerusalem. “I try not to miss it.”

golden haze of last light as long as possible before fading to a silhouette on the western skyline. “I really enjoy watching the sun set over Jerusalem every night,” says Justin B. Top, a BYU student who spent winter semester 1999 in Jerusalem. “I try not to miss it.”

Long after they return home, students remember that view. From the Arab village around the center to the gleaming roof of the Dome of the Rock mosque across the Kidron Valley, Jerusalem seen from that angle imprints itself indelibly on the memory. Center director R. J. Snow says, “I can’t look out my window without having a spiritual experience.”

THE HOLY CITY

I was glad when they said unto me, Let us go into the house of the Lord. Our feet shall stand within thy gates, O Jerusalem. —Psalm 122: 1–2

Set high on Mount Scopus, just north of the Mount of Olives, the Jerusalem Center overlooks the Kidron Valley and the Old City of Jerusalem.

The Old City of Jerusalem is, for most American visitors, pungently foreign. Naked carcasses of beef and lamb hang suspended in open-air meat shops, and veiled women display mounds of vegetables along the sidewalks. Camels and donkeys may be parked alongside taxi vans. Five times a day the Muslim call to prayer comes keening from the minarets. And every Friday at sundown a procession of Jewish yeshiva students goes singing and dancing to the Western Wall to welcome the Sabbath. The religious and political passions of this land far exceed anything most BYU students have experienced firsthand.

“No matter what they dreamt this was going to be like, they couldn’t have imagined it,” Snow says. “We see students awestruck and wide-eyed from the day they get here until the day they leave because there is such an extensive variety of experiences for them.”

BYU‘s study program in Jerusalem began in January 1968 when Daniel H. Ludlow, then dean of religious education, and his wife, Luene, led a group of 20 students to the Holy Land for a semester. The program grew steadily, and in 1979 LDS Church President Spencer W. Kimball announced the decision to build a permanent BYU facility in Jerusalem. Final approvals for leasing land on Mount Scopus (which lies just north of the Mount of Olives) were obtained in 1984; students moved into the unfinished building in March 1987, and the Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies was dedicated in 1989.

The center’s resources have allowed BYU to host more students (an average of 170 in each of five programs; about 810 a year) and offer them amenities their predecessors hardly dreamed of: air conditioning, laundry facilities, large lecture halls, computers and e-mail, and a cafeteria that at times serves such delicacies as hamburgers and doughnuts. Today’s students rightly realize that they are cared for exceptionally well. “We live in a palace compared to anywhere else in Jerusalem,” says Heidi Madsen, a Utah State University student from Salt Lake City.

Old Jerusalem is still bounded by the stone walls built in 1537–39 by Suleiman the Magnificent, one of Jerusalem’s early Ottoman rulers. (The “new” city, a Jewish portion that has sprung up to the west since the 1947 partition of Palestine, is far more modern.) Most of the Old City’s labyrinthine streets are too narrow to admit a car. Signs may be posted in at least five alphabets—Roman, Hebrew, Arabic, Cyrillic, Greek—and there are enough varieties of religious and ethnic garb to fascinate any young traveler.

Head covered with a paper kippah, BYU student Nathan Sanders writes a prayer at the Western Wall. The wall, a remnant of Herod’s temple mount, is the most sacred Jewish site in the world.

“I’ve loved watching people of other faiths in their devotion,” says Afton B. Sessions, a BYU English major from Encinitas, Calif. “I remember the first time I went to the Western Wall I was in tears watching the men dancing to usher in the Sabbath.” With its polyphony of languages and faiths, cultures and costumes, the city is eclectic and intoxicating.

One of the first memorable experiences that comes to every student is the accurately targeted greeting of an Arab merchant calling, “Mormons, welcome!” The city’s Muslim and Christian quarters are full of street-side shops offering pottery, olive wood, textiles, and all kinds of souvenir trinkets for the hordes of tourists that flow along their narrow streets. Most shop owners are prepared to haggle in several languages, and they have also become adept at recognizing students from the center.

Then again, the shopkeepers must see groups of students several times a day, as they tramp by en route to the holy or historic sites on their syllabus. “Drive around in the city and you see our students everywhere,” says Matthew S. Chipman, a Church Educational System (CES) teacher from South Jordan, Utah, who taught at the center during the 1998–99 school year. “They are known, and everybody knows where the ‘Mormon University’ is.”

Located high on Mount Scopus, just south of Hebrew University, the center is an easy landmark. Its cascading limestone arches make it one of the most striking buildings in Jerusalem. And students need only 15 minutes to walk down the hill, cross the Kidron Valley, and enter the Old City. They tend to grow restless when schoolwork keeps them away.

Students (from left) Heidi Sanders, Keli Kartchner, and Christy Meldrum shop in one of Jerusalem’s crowded street markets.

“Someone told me that if I spend my entire time in the center studying I might as well just tack up a picture of the Old City on my wall in Provo,” says Adrianne Parker Murdock, a BYU nursing major from Salt Lake City. “So that’s always been my motivation—to get out and see it and hope to apply what I’m learning. It doesn’t do me any good just to sit here and not experience the whole beyond-the-book story.”

Most of the fear and some of the wonder of the foreign city fades as it becomes familiar. Though one never quite becomes careless, after a visit or two it is no longer unsettling to walk through a crowded bazaar. Though one never ceases to notice them, before long it is nothing extraordinary to see font-like ceremonial baths, or mikvot, at excavation sites. Though they always spark (and demonstrate) curiosity, it becomes commonplace to see young Muslim girls wearing school uniforms and white scarves that completely cover their hair. After a week or two in the center, many students hardly consider their daily opportunity to walk along the Via Dolorosa, the “Way of Sorrows” over which, tradition says, Jesus carried the cross.

“We walk down the Via Dolorosa and we say, ‘I’ve walked down this every day, and I haven’t taken a picture of it,’ although people travel thousands of miles to see this,” says Jennifer A. Johnson from Murray, Utah, now a BYU MBA student. “I need to figure out how to take this home—because eventually I can’t wake up in the morning and walk down the Via Dolorosa.”

A SCHOOL IN ZION

I will bring them, and they shall dwell in the midst of Jerusalem: and they shall be my people, and I will be their God. —Zechariah 8:8

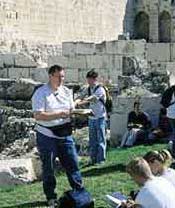

CES teacher Matthew Chipman and his Old Testament class study among the massive stones in the Ophel Archeological Garden, an excavated area south of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.

Just inside the present walls of the Old City of Jerusalem stands St. Anne’s Church, so named because it is built over a grotto where, according to legend, Anne gave birth to Mary, Christ’s mother. Outside the church the ground opens into deep cisterns, now rimmed by metal railings. In Herodian Jerusalem this was the site of the pool of Bethesda, that pool by the sheep market where Christ healed a man who had been infirm 38 years (John 5:1–9). It is one of the few biblical sites in Jerusalem about which there is no uncertainty. Layered over the bedrock reservoirs are generations of newer stones—the crumbling foundations of late Roman-era baths, the myriad tiny stones of a mosaic, clean-cut chunks that were the pillars of a Byzantine church, window frames from what was once a Crusader monastery.

It doesn’t take long for most students to recognize the historical periods represented in those tumbled ruins. “History has never come to life like it has since I’ve been here,” says Caleb J. Beard, a BYU student from Renton, Wash. “It’s not entombed in the ancient stone ruin of a wall. Because the people are so connected to their history, it lives in their hearts today.”

Taught by BYU professors and local Palestinian and Israeli scholars, the center’s Near Eastern studies courses give students a whirlwind survey of the region’s geography, history, present-day politics, and cultures. The core curriculum also includes religion classes focused on the Old and New Testaments and introductory classes in Hebrew or Arabic. Semester-length programs offer elective courses on subjects such as women of the Old Testament, biblical concepts in Jewish practice, Arab family and culture, and the Crusades.

Some students, perhaps expecting a more meditative pace, are surprised by the rigor of the academic program. But before the semester ends, most can identify Roman structures, speak knowledgeably of significant historical groups—from the Philistines and Essenes to the Maccabees and Mamelukes—characterize important Jewish and Muslim holidays and doctrines, and spout off the successive occupations of Jerusalem.

“Sometimes from the moment I wake up to when I go to bed, every moment I learn something or I’m feeling the Spirit,” says Ashlee M. Ainge, a BYU communications major from Gilbert, Ariz. “And I feel so full of knowledge—more than I can hold all at once.”

Students (from left) Anna West, Ashlee Ainge, Emily Hall, and Adrianne Parker test the purported skin benefits of Dead Sea mud. Most students build strong friendships during their time at the center.

Most students at the center are enrolled in the core Near Eastern studies/religious studies program. Every year there is also a

After a sweltering trip to the desert fortress of Masada, Daniel Stewart (left) and Shawn DuBravac use their well-worn guidebooks to demonstrate the buoyant properties of the Dead Sea.

semester-long intensive language program (Hebrew or Arabic, in alternate years) that admits about 18 students who share dorm space with the larger groups but have an entirely different curriculum. And every other fall Ricks College sends a group of student nurses to work in local hospitals.

The Ricks College nurses are just a few of the non-BYU students who come to the center. Though administered by BYU, the Jerusalem Center is actually a First Presidency project, planned and overseen by prophets and apostles. It draws religion faculty from BYU, Ricks College, and CES and accepts students from around the world. In a summer 1999 pilot program, for example, the center hosted 19 students from northern Europe. Dann W. Hone, a Jerusalem Center program administrator, says the center receives about three applicants for every available slot, and roughly 40 percent of those who apply are not BYU students.

Though a semester in Jerusalem may not relate directly to their majors, most students find it an extraordinarily enriching university experience. “This has been a great lesson in seizing the day and taking every opportunity,” says Melinda Holt, a BYU music major from Enterprise, Utah. “We try to get the most out of every minute here.”

TREKKING FROM DAN TO BEERSHEBA

Walk about Zion, and go round about her: tell the towers thereof. Mark ye well her bulwarks, consider her palaces; that ye may tell it to the generation following. —Psalm 48:12–13

BYU history professor William Hamblin leads a field trip through the streets of Old Jerusalem. The headphones enable students to explore a site and still hear their teachers’ explanations.

The center’s curriculum is coordinated so that as students discuss biblical events in their religion classes, their history and Near Eastern studies classes cover the same era or region. Whenever possible, their weekly field trips provide a tangible introduction to the places and texts they’ve been studying.

And the more tangible the better. At the Dead Sea, for example, after floating in the super-salty water, students may slather themselves with mineral-rich mud. Some, like Daniel H. Stewart, go the extra mile to capture the moment. “We take our Archeology of the Holy Landbooks all over the place,” says Stewart, a BYU history major from Henderson, Nev. “We went into the Dead Sea and read them—got a picture of us reading them and floating—and then we opened them up to the page that has the map and the article about the Dead Sea, and we dipped it into the water. It got really glossy when it dried; it’s really salty. So anytime we want to remember how the Dead Sea was, we can just lick it and remember.”

A typical field trip includes at least one destination called a tel, a Hebrew word meaning, in general, “a partially excavated pile of rocks.” At least that’s the definition students construct after they have spent hours riding to and tramping among the mounds of dirt and stones that are the remnants of cities like Dan and Beersheba, settlements that marked the northern and southern boundaries of ancient Israel. At some ancient sites potsherds are strewn like seeds across the soil. All of the historic places are, fundamentally, just rocks, as students soon discover.

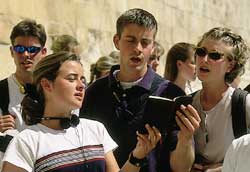

Led by impromptu chorister Jeremy Stewart, students and faculty from the Jerusalem Center gather to sing hymns and enjoy the inspiring acoustics of St. Anne’s Church.

Still, when linked with scripture, rocks can be inspiring. In the valley of Elah where David slew Goliath, students typically try to fling a few rocks by slingshot. They may use rocks to mark the dimensions of the tabernacle that stood at Shiloh. While at Mount Carmel, re-enacting the story of Elijah and the priests of Baal, they may build an altar with 12 stones. And in the Judean wilderness between Jordan and Jerusalem, while talking of Christ and His perfect responses to temptation, they can pick up loaf-sized stones.

For those who are on the right spiritual frequency, the rocks do not hold their peace.

“I can remember looking down at the Wadi Kelt, and the group had just sung and I’m thinking to myself, This is the spot where John the Baptist walked and where Jesus Christ walked to get to the Mount of Temptations. This is where the story of the good Samaritan took place.And everything came to life,” says Jonathan S. Gardner, a University of Utah business major from Centerville, Utah. “I remember coming home and writing that in my journal and just feeling overwhelmed. I felt as if I was right there.”

LIVELY STONES

Ye also, as lively stones, are built up a spiritual house. —1 Peter 2:5

A dusty road through the Kidron Valley carries camels and chickens, children chasing soccer balls, heavy construction equipment, and the clusters of BYU students who walk down the hill from the center and cut through the Kidron, usually en route to Stephen’s Gate, the easternmost entrance to the Old City of Jerusalem. As students walk south through the Kidron, the Mount of Olives rises at their left. BYU‘s Jerusalem Center stands behind them on its northern flank; at mid-mount an onion-domed Russian Orthodox church stands just above the Franciscan Catholic Church of All Nations—the traditional site of the Garden of Gethsemane.

On a typical Sabbath afternoon, between the set times for church services and dinner, students leave the center in small groups and walk south through the Kidron to Gethsemane, where a caretaker may admit them to a gated garden where there is long light, quiet grass, and space for meditation.

In the same Sabbath-afternoon time frame and with similar motivation, other groups walk around the north edge of Old Jerusalem to the Garden Tomb, where they read and pray and write. Watching the ever-present pilgrims file through the garden, students recognize the luxury of their time to linger and return. Though the spices and traffic of the Old City always beckon, it is the sacred sites that feel most like home.

St. Anne’s Church is yet another favorite Sabbath destination. Its sturdy, unadorned walls create acoustics fit for angels. And students from the Jerusalem Center come there regularly, hymnbooks and tape recorders in hand, to fill the stone church with glorious echoes.

Sacred music is an important part of the Jerusalem Center experience. Groups generally have scads of musical talent; often there will be a student or two who can play the auditorium’s pipe organ or compose music inspired by the Holy Land. In some semesters more than 140 students show up for branch choir practice in the center’s glass-walled auditorium.

“All the music adds a really nice dimension,” says Vaughn R. Kimball, a Weber State University biology major from Layton, Utah. “I’ve never sung so much as I have here.”

Hymns are also part of every field trip. On a bus headed for the mountain fortress of Masada, classes sing military hymns like “We Are All Enlisted.” In the wilderness near Jericho, after pondering the parable of the good Samaritan, they sing “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief.” They sing in churches and caves, on top of Mount Sinai, and beside the Sea of Galilee.

They sing Christmas carols under starry skies at Shepherds’ Field outside Bethlehem. And on the rocky hilltop of Bethel, where Abraham built an altar and Jacob wrestled with an angel, they sing “Nearer, My God, to Thee.”

Nearly every student mentions spiritual growth as a primary reason for coming to the Holy Land. Many come expecting that a visit to a major site will be overwhelmingly powerful. And most of them do carry home sweet memories of the traditionally hallowed places. Yet they quickly understand that the sites are secondary—catalysts to spiritual growth, perhaps, but not the source of the reaction.

“The traditional spots are neat, and they’re beautiful,” says Matthew L. Pinegar, a BYU film major from Orem, Utah. “But the Spirit is with us already, and it can testify to us of these miracles anywhere. I think a lot of people have learned that it’s not necessarily being where Jesus was and seeing what He saw, but doing what He did and following His example.”

Still, he admits, there’s nothing quite like being there. There’s a lot to be said for traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho and thereby understanding for yourself why the “certain man” rescued by the good Samaritan went down to that city. Though they serve it with head on and eyes bulging, it’s pretty fun to eat a fish from the Sea of Galilee. And when you plant your feet on a pavement stone where Christ may have stood, He becomes somehow more tangible. Pinegar says he came to Jerusalem to gain some of the scriptural perspective Nephi had when he wrote: “I, of myself, have dwelt at Jerusalem, wherefore I know concerning the regions round about” (2 Ne. 25:6).

ON MOUNT ZION

They that trust in the Lord shall be as mount Zion, which cannot be removed, but abideth for ever. As the mountains are round about Jerusalem, so the Lord is round about his people from henceforth even for ever.

—Psalm 125: 1–2

On a typical evening at the center, some of the students are squirreled away in their rooms or in the library; some are writing e-mail. But others gather for a game of Trivial Pursuit on a landing, a study group in a classroom, or a trip by sherut (taxi van) to buy ice cream on Ben Yehuda street in the “new” city. There may be swing dancing instruction on the stage and aerobics, folk dancing classes, or basketball tournaments in the gym. Anyone is welcome at any activity, and a passerby never lacks an invitation to join the fun.

On a typical evening at the center, some of the students are squirreled away in their rooms or in the library; some are writing e-mail. But others gather for a game of Trivial Pursuit on a landing, a study group in a classroom, or a trip by sherut (taxi van) to buy ice cream on Ben Yehuda street in the “new” city. There may be swing dancing instruction on the stage and aerobics, folk dancing classes, or basketball tournaments in the gym. Anyone is welcome at any activity, and a passerby never lacks an invitation to join the fun.

“It’s been very interesting being a part of this group,” says Adam P. Ash, a BYU zoology major from Mesa, Ariz. “They throw you together, and you don’t have any choice of who you’re going to be with. Yet sometimes I feel this is what God wants us to learn—He wants us to be able to get along with every kind of person.”

Whatever else it might be, the Jerusalem Center is a laboratory for building Zion, in the “of one heart and one mind” sense (see Moses 7:18). For all their diversity in age and experience, and for all their simple human faults, the students are fundamentally of one heart and one mind. Seemingly without exception they want to be good. They come to Jerusalem desiring to know more of Christ, and they help each other know Him.

“As I watch people in my classes, I see attributes and characteristics that I strive for,” says Shawn G. DuBravac, a BYU international

Once each semester, students enjoy a traditional Bedouin feast – chicken, rice, and pinenuts in a yogurt sauce, eaten with bread instead of utensils – in an authentic Bedouin tent.

development major from Alexandria, Va. “I think that’s one of the great advantages to living with so many people, so close. I live next door to my role model when it comes to love. And I live across the hall from my example of humility. And so as I’m in the city learning about Jesus Christ, I’m also witnessing all those miracles that He performed, in each one of us. I’m witnessing people who have humility like the child Christ talked about. And I’m witnessing people who live that new commandment and love one another and show that they are His disciples.”

Folk dancing lessons are a popular weeknight option for students at the Jerusalem Center. The center’s facilities allow for a variety of recreational, cultural, and sports activities.

It may be relatively easy to imitate Christ in the center’s setting. For one thing, the program eliminates many of the variables that typically divide people. Everyone’s meals and living conditions are identical. No one, typically, is fluent in the dominant local languages. Everyone has a calling in the LDS branch or a responsibility in the student government. Everyone travels to the same places and has roughly the same opportunities.

The program also eliminates many of the social distractions that might interfere with opportunities for service and growth. Though students sometimes come with a sibling or a best friend, no one has a pre-set clique. No one, except sometimes the children of faculty, has a parent to go home to. Though plenty of sweethearts get left at home and some people do, therefore, receive affectionate correspondence, no one ever has a “date.” Dating of any kind is forbidden, though groups often produce several eventual marriages.

Program policies definitely encourage group-mindedness—the students’ little apartments are shared by four people, and no one

Students participate in a Sabbath School class. To conform with local schedules, and by special permission from the Church, the Jerusalem Center holds LDS services on Saturdays.

can leave the center without at least two companions. Concern for each other soon becomes instinctive. Whether sloshing through Hezekiah’s Tunnel, clambering in predawn darkness up the steps of Mount Sinai, or trudging up the Mount of Olives toward the center, someone always waits for the straggler.

“You’re never alone, and I think this is an amazing experience because of that,” says Audrey A. Bastian, a BYU history major from Provo. “I think, in the end, I changed because of the people around me.” Bastian came to Jerusalem for a semester in 1997 and returned in 1999 for the intensive Arabic program. On her first trip “we bonded so tightly that I was not only able to learn about this land and the Bible and religion, but I was able to put it into practice in a very close-range setting,” she says. “That was the magic of the program for me.”

CHILDREN OF ISRAEL

If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth; if I prefer not Jerusalem above my chief joy. —Psalm 137:5–6

Nathan Toronto (center) taught an English class for these Palestinian boys. He and other students in the center’s intensive Arabic program regularly volunteered at a local school.

Part of the luxury and the miracle of the Jerusalem program is the way it separates students from past contexts and gives them new peers, new understanding of history and scripture, and a new vantage point from which to see themselves, their home nations and cultures, their faith and their future.

“I didn’t picture it being as life-changing as it ended up being,” says Caleb Beard. “I think I’ll look back through my whole life at Jerusalem as sort of a pivotal event, and I’ll see changes that came about in my life because of it.”

For students privileged to spend time there, Jerusalem may change the very rhythms of the blood. They learn to feel new kinship with all the peoples of the earth, especially with the vigorous and watchful people who are the children of this land—the zealot and the agnostic, the urbanite and the Bedouin. “It’s the living part of the land that has taught me,” says Amanda L. Duncan, an international politics major from Richmond, Va. “It’s the people that have made me love this land.”

Students who fall in love with the city and its people catch what Tamee Roberts calls the Jerusalem bug. “Once you catch it you’re stuck. You have to come back, you have to do something with the Middle East. And, yeah, it’s like a disease.” Roberts, now a BYU alum from Sandy, Utah, first came to Jerusalem during summer term 1997. She wanted to return so badly that she arranged to do her student teaching at a Palestinian-American school in 1999.

If there are such things as archetypes born into the marrow of humankind, and if places can have that visceral magnetism, then Jerusalem is one of them. For centuries the city has been a lodestone for the faithful of every Muslim, Christian, and Jewish sect. It is one of the original places of pilgrimage. Allow the city to capture you and you will understand, if only superficially, the call of ancestry and homeland and prophecy that motivated the Passover mantra of diaspora Jews: “Next year in Jerusalem.”

There is nearly always at least one in each Jerusalem Center group who becomes a scholar of ancient things or modern problems, who returns to dig or write or serve. Dann Hone, for example, first came to Jerusalem as a student in 1973. Soon after returning home he was hired to help develop the program, and he has been with it ever since. Hone and his family lived in Jerusalem from 1985 to 1992, and though he now works on the program from BYU‘s Provo campus, he tries to return to Jerusalem at least once every year. “We miss it over there immensely,” he says.

“It’s a curious thing about Jerusalem: One visit seldom satisfies a member of the Church,” says David B. Galbraith, a BYU associate professor of political science who lived with his family in Jerusalem from 1969 to 1988 and directed the program during the last 15 years of his stay. “All that we hold sacred and dear in history—so much of it has transpired in that land. So we’re not surprised that we are drawn there. Nor should it surprise anyone that we have a program to in a sense help us discover our religious roots.”

NATURAL FRUIT

The Jerusalem Center gardens feature trees, plants, and artifacts characteristic of Bible times. Each year the students make oil and juice from olives and grapes grown on center property.

He shall cause them that come of Jacob to take root: Israel shall blossom and bud, and fill the face of the world with fruit. —Isaiah 27:6

The center’s magnificent auditorium opens onto what is arguably the best view in Jerusalem. On a clear day you can gaze from Bethlehem on the south to Nebi Samuel, traditional burial place of the prophet Samuel, on the north. Among the sweetest things students carry home in their hearts are that incomparable vista and other memories of light:The way the sun rises red over Sinai. Shadows cast by half-felled pillars at Capernaum. The dim interiors of ancient churches. Smiles from Egyptian children. The brightness of the center’s terraces at midday. Late afternoon light filtered through olive branches.

On Jerusalem Center grounds there is a biblical garden with olive trees, two olive presses, grapevines, and, built into the ground, a Roman-style winepress. Every fall, students crush their crop of olives into oil, which they consecrate for blessings. They also make new wine by wading barefoot in the winepress and tramping the juice out of the grapes. After which they drink it—part of their purpose in coming is to taste the land’s natural fruit.

There is much fruit to be had in Israel. From Jezreel to Jericho, students see groves of trees bearing grapefruit, bananas, figs, olives, dates. When their semester ends, students may take home these or other products of the land: olive-wood carvings, sandals, chocolate bars, genuine Dead Sea mud. But what they prize most is fruit of a more metaphorical variety—eyes that see, ears that hear, and hearts that understand.

Amy Blake ponders at the Garden Tomb. Journals filled with spiritual insights are among the most cherished things students take home from the Holy Land.

By grafting themselves for a time into the soil and traditions of the Holy Land, Jerusalem Center students are nourished by the roots of faith still thriving there. They go home to widely varying plans and paths, but nearly all express a resolve to be fruitful.

“This is the first time I have learned how to live,” says Jasmin K. Rashid, a BYU public relations major from Midway, Utah. “This is what I am taking home with me. I don’t think any of us quite know yet what we have learned and how important this center is.”