Sketches of Saints

A religion class brings to life Latter-day Saints from the Church’s beginning to present day.

By Maddie Gearheart Nordgren (BA ’12) in the Spring 2013 Issue

Illustrations by Greg Newbold (BFA ’92)

It’s story time in 174 JSB, and students have gathered to hear David F. Boone (BA ’78, MA ’81, EdD ’92), associate professor of Church history, teach important gospel principles while spinning yarns about cowboys, poets, pioneers, and civic leaders.

This is Men and Women of Mormondom, a one-credit class that studies how individuals, prominent and obscure, have lived the gospel since 1830.

Some of the names Boone teaches are familiar—like Parley Pratt, missionary; Jane James, African-American pioneer; and Eliza Snow, Relief Society president. Others aren’t so recognizable—like Willard Bean, boxing missionary; Sam Cowley, special agent; and Ellis Shipp, one of Utah’s first female doctors.

“When you study these lives, you have so many good stories that start to fit into different situations in your life,” says student Lorna Jacobs Reed (BA ’78). “You see how these people . . . can influence our lives for good.”

Boone has long been interested in biography. As an undergraduate, he enrolled in Men and Women of Mormondom, instructed by Ivan J. Barrett (MA ’47), who pioneered the class and taught it in his 40-year tenure. “He was a hero of mine,” says Boone, who joined the staff in 1984 and begged to continue the class.

Considering that “Mormondom” constitutes a planet-sized geographical span and 183 years, he has quite the task choosing the 12 or 13 people he’ll lecture on each semester. While Boone is particularly fascinated with 19th-century Church history, he also scours personal histories from the 20th and 21st centuries. When he finds an intriguing thread about someone, he’ll grab a new folder and start collecting stories. When the folder is bursting with sources, it’s time.

Historic settings help vivify history. At the end of a semester, the class takes a field trip to Echo Canyon, Mormon Flat, and various sites in Salt Lake proper to see for themselves where Saints came and went, lived and died.

Brother Boone and his students will tell you the biggest takeaway of Men and Women of Mormondom is the way the stories transform the listeners. Following are stories and brief bios of a handful of characters brought to life in class. In the words of student Jessica M. Johnson (BA ’12), “It’s amazing to realize that all these different people—some you’ve never heard of—can do great things. It gives a person hope that maybe you can make a difference in someone’s life.”

Willard Bean (1868–1949): The Fightin’ Parson

In 1890s Tennessee, a bloodthirsty mob tied two Mormon missionaries to a tree one afternoon and debated what to do with them. One of the missionaries called out, “You’re the biggest bunch of cowards I’ve ever seen. Where I’m from, they let a man fight. Turn me loose,” he challenged. “I’ll fight you two at a time—and I’ll whip the whole bunch of you.” Eager to test this claim, the mobsters cut him loose.

“This puny little guy,” says Professor Boone, clobbered four pairs of them before the group finally started to disintegrate. But before they could get very far, the missionary said, “Don’t go away mad. I can preach better than I can fight. Now sit down.” They did.

Meet Willard Washington Bean, boxer-missionary extraordinaire. “His tactics of teaching the gospel were second to nobody’s,” says Boone. And it was a good thing, too, since between his stints as a Brigham Young Academy student, a PE teacher in Utah, a professional boxer in San Francisco, and the coach of future heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey, Bean had a knack for getting called to the most hostile, anti-Mormon missions of his time.

Years after his mission to the South, Bean and his wife, Rebecca, were called to reintroduce the Church to Palmyra, N.Y. In 1915 they moved into the old Smith farmhouse, where a “welcome” party soon arrived and hinted they had better move on. When it was clear the Beans weren’t going to budge, the town changed tactics, ostracizing the entire family instead. Boone says the townspeople crossed the street when they saw the family coming, forced one child to wear the dunce cap in school, and refused to sell them groceries or even midwife for Rebecca.

After several years of work and little progress, Bean decided it was time to resurrect “Kid Bean,” the fightin’ parson. He rented a hall, set up a ring, and challenged the men of Palmyra to come and take their chances to finally whip a Mormon.

It was Tennessee all over again. Bean not only took his foes out in quick succession but also started doing somersaults and calisthenics between opponents. “He’s an old man,” Boone exclaims, “and he’s doing somersaults!“ People were suddenly kinder to the Beans and more open to attending the Mormon Sunday School.

Bean’s physical prowess and firm, fearless attitude were two of his most defining characteristics. But he was as loving as he was agile, and even when his own safety was in danger, he used boxing—ironic though it be—as a path to people’s hearts rather than a way of exorting them. From his boyhood, Boone says, “Instead of making an enemy of [his opponent] and gloating, he would pick him up and make a friend out of him.”

This pattern had clear echoes in Bean’s later life. When he and Rebecca returned to Utah 24 years after arriving in Palmyra, they left behind not only a thriving branch but also an entire town of bosom friends.

Jane Manning James (1822–1908): Pressing Forward

Eager to join the Saints, James and her family set out for Nauvoo a year after their baptisms. But at one port, the ship captain demanded papers proving their status as free blacks—papers that none of them had, having never been slaves. They were miraculously let on without them, but at the next port in Buffalo, N.Y., the ship sailed away with their bags, leaving them destitute.

James’ faith and desire for spiritual community were so strong, says Boone, that the family continued the journey of several hundred miles—on foot.

In an autobiographical sketch, she recalled, “We walked until our shoes were worn out, and our feet became sore and cracked open and bled until you could see the whole print of our feet with blood on the ground. We stopped and united in prayer to the Lord, we asked God the Eternal Father to heal our feet and our prayers were answered and our feet were healed forthwith.”

“A lot of the members would have fallen off the trail before that,” Boone notes, echoing the sentiments of one Dr. Bernhisel, who was with the Prophet when the devoted band arrived penniless. Emma and Joseph eventually invited James to stay in their home, and James grew close to them, says Boone. She was heartbroken when the Prophet was martyred, but she and her new husband, Isaac James, pressed forward into the West, becoming two of the first African Americans to settle in Utah.

Throughout her life she had great spiritual gifts. During her time in the Prophet’s home, she received a spiritual witness about the significance of temple clothing just by seeing it among the laundry and pondering it at length. Although James wasn’t able to receive her temple blessings during her lifetime, she remained faithful.

“And,” says Boone, “she was a really significant contributor after the Church came West.”

Known for her generous spirit, despite ups and downs in her economic prosperity, James once gave Eliza Lyman, who couldn’t get flour until after harvest, two pounds of the stuff—“it being about half of all she had,” wrote Lyman. James was also known for her association with the Prophet, says Boone, and was accordingly honored with a prominent seat on the stand each Sunday in her Salt Lake City ward. One Anna Shipp recalled seeing James and her brother Isaac each week. “They were devoted Latter-day Saints,” she wrote, “and everyone in the Third Ward loved and respected them.”

At James’ death in 1908, the Deseret News observed, “Few persons were more noted for faith and faithfulness than was Jane Manning James, and though of the humble of the earth she numbered friends and acquaintances by the hundreds.”

As a young woman, Jane Manning James heard a Mormon missionary preach in her Connecticut hometown and was baptized a week later. “When the gospel came,” says Professor Boone, “she took it and ran with it.”

Stella Harris Oaks (1906–80): Mother and Mayor

When her husband, Lloyd, died after almost 11 years of marriage, Stella Harris Oaks (BA ’28) faced the prospect of raising three children alone and felt strongly that she needed more education. The following years demanded every ounce of her strength, but with family support, Oaks received a master’s in guidance and personnel administration from Columbia University.

“This was the 1940s,” says linguistics professor Dallin D. Oaks (BA ’84), Stella’s grandson—and one of many guest speakers Professor Boone has invited to class to help bring his selected historical figures to life. “For a woman to get a master’s degree at Columbia University . . . was a remarkable achievement.”

But Stella Oaks was a woman passionate about education—and doggedly determined.

Oaks graduated at the top of her class in high school; received a teaching certificate along with her bachelor’s in dramatic arts; helped put her younger sister through college; worked as a high school teacher; and served as director for adult education in Provo. Work was fun and fulfilling for her from a young age: while thinning beets with her siblings, she’d entertain them with stories, and they had to work hard to keep up with her or they would miss out. Even while battling lymphoma in her later years, Oaks was full of energy and purpose—once giving a presentation to a committee that included the Relief Society general presidency the same day she’d had a hospital treatment.

The dark period she endured when Lloyd died deepened her compassion. “She genuinely loved people and cared about them and how they felt about themselves,” says Professor Oaks. “She spoke well of everyone, and she tried to see the good in all.”

Beginning in 1955, Oaks served two terms as the only city councilwoman of Provo and one term as assistant mayor, a visible career that made her widely known and respected, says her grandson. She was constantly requested as a guest speaker. Once, the postal service directed a letter whose envelope read only, “Stella Oaks, Salt Lake City,” to her home in Provo. Another time, a teenage girl called her to ask when it was all right to kiss boys.

But above all else, says Professor Oaks, Stella served her family. In one family story, she sent her brother and his family on a weeklong getaway to Yellowstone, ignoring his protests that he had a farm to run. “Do you think I’ve forgotten how to milk a cow?” she asked. In another story, she trusted her 14-year-old son, now Elder Dallin H. Oaks (BS ’54), to bus himself to Denver to take a radio-licensing test.

Professor Oaks says his grandmother’s faith kept her going. “I watch for little signs or signals each day that the Lord is watching over me,” she once wrote. “A thousand things each day show me that He is concerned about me and that He loves me.”

Orrin Porter Rockwell (1813–78): A True Friend

Most Mormons equate Porter Rockwell with the “rough-and-ready, shoot-’em-up, Wild West persona,” says Professor Boone. To be sure, Rockwell’s role as a territorial deputy U.S. marshal and reputed sharpshooter branded him as an Old West hero (disputed hero, that is—“If you weren’t an outlaw,” says Boone). But there was certainly more to Rockwell than guns and horses and draws.

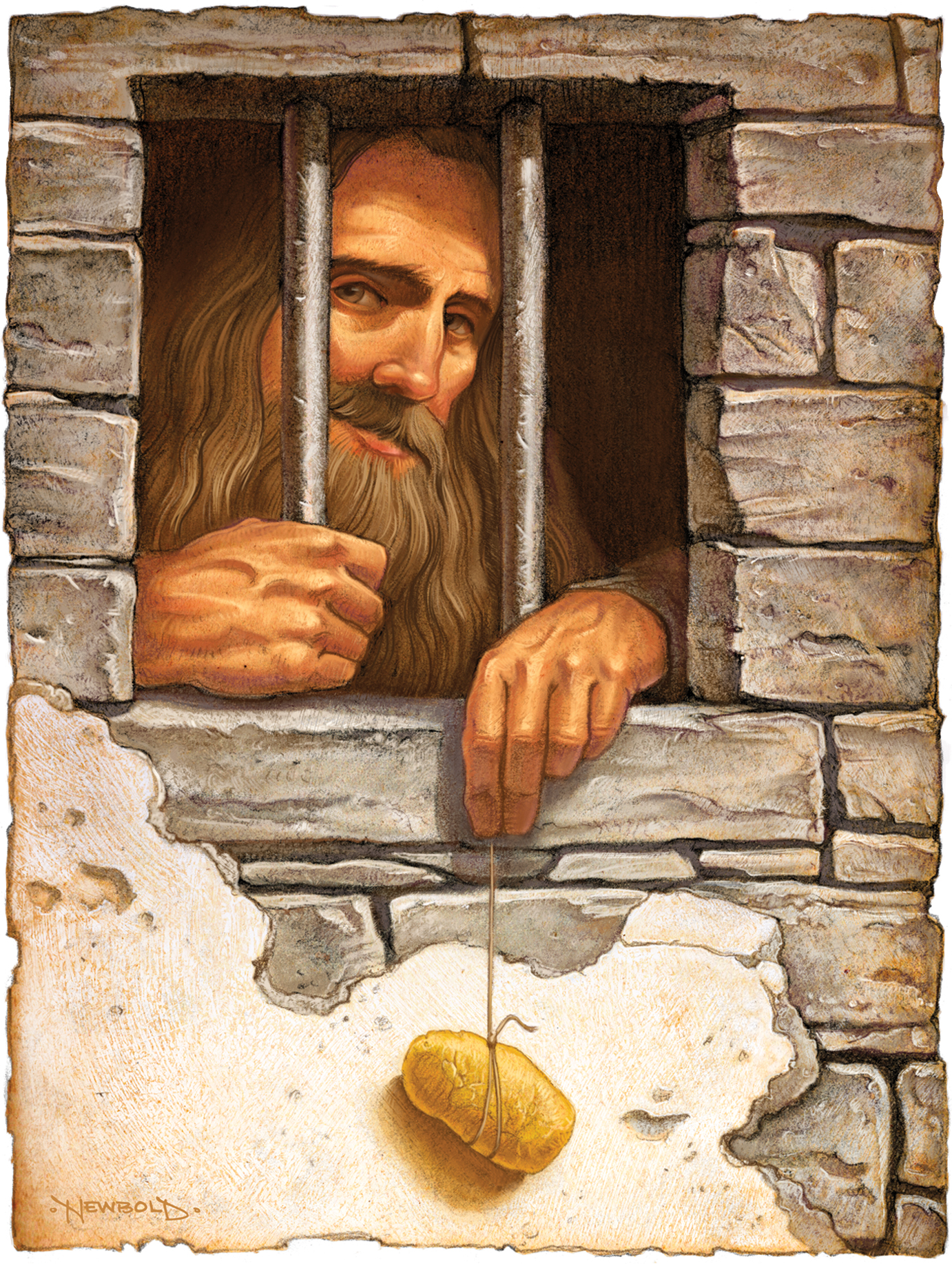

He had a delightful sense of humor. For nine months, Rockwell sat in a Missouri prison without trial and without sentence. At the time neither the city nor the state was legally responsible for feeding Rockwell or any other prisoner, so the good citizens of Missouri provided food from their own tables. For comic relief, Rockwell would tie hardened lumps of fried cornbread called “corn dodgers” on strings and dangle them out the window. Children confronted him from outside the prison walls. “What are you doing?” they asked. “Fishin’ for pukes,” he replied—“pukes” being a derogatory nickname the Illinoisans called the Missourians. “Any bites?” they said. “Nope—but had some glorious nibbles!” The children would stick around, dissolving into laughter when an adult passed and encountered the wriggling victuals hanging from a barred window. “The mental image of it makes me chuckle,” says Boone.

Rockwell also had a softer side, especially for the Prophet Joseph. The two grew up together in Palmyra, and Rockwell stuck with Joseph along every stop on the journey to Nauvoo. “They loved each other,” says Boone. “I think the Prophet’s friendship with him was unlike his friendship with anybody else.” When Rockwell heard the news from Carthage, he is reported to have said, “They have killed the best friend I ever had.”

“He seemed like two different people before and after Joseph’s death,” Boone says. Introverted and quiet before, he became loud and gregarious. That’s what made him so perfect for his eventual position as a deputy U.S. marshal, says Boone; with confidence, bravado, and spunk, “He always got his man!”

Rockwell shared his gentle side with others, too. Boone says accounts suggest that upon his safe return from prison, Joseph issued Rockwell a Samson-reminiscent mandate: don’t cut your hair, and “neither bullet nor blade” will take your life. From then on Rockwell wore his hair long, sometimes braiding it up under his hat so criminals wouldn’t recognize him from far away. But years later, Rockwell surrendered his hair to make a wig for one of Joseph’s sisters-in-law, who had lost her hair to typhoid fever. It appears, says Boone, that he was willing to forego the potential spiritual protection of keeping his hair to help someone who was dear to the Prophet.

Amanda Barnes Smith (1809–86): Backbone of Steel

Most people wouldn’t come within miles of a mob leader who led a killing spree on their family—not to mention their entire religious community. But not Amanda Barnes Smith.

Smith grew up in Massachusetts and Ohio, where she met and married her husband, Warren, and converted to Campbellism—thanks to future LDS leaders Orson Hyde and Sidney Rigdon. Several years later she and Warren were baptized into the Church and participated in the settlement of Kirtland and the building of the temple there.

But it wasn’t until Missouri that Smith’s story became well-known. Just days after her family arrived there, her husband and second son were killed in the Haun’s Mill Massacre, and one of her 6-year-old twins, Alma, had his hip blown completely out by gunshot. Mere days later, people flocked to the area to hear the story of his miraculous healing, the alleged result of a mother’s prayer. “Christ was the physician,” Smith said, “and I was the nurse.”

Professor Boone likes to share a lesser-known story about Smith. A few days after the massacre, the order came for the Mormons to leave the state. Robbed of all her possessions, Smith had no provisions and no transportation except her feet. “She had a backbone of steel,” Boone says: she left her four children at the site of the massacre, walked to the mob leader’s home, banged on the door, and said, pointing to the livestock, “You have my horse.” When the mobster wanted to sell it to her and then charge her for having fed it, she firmly replied, “No. I don’t have any money. It’s my horse. I need it. I’ll take it now.” One account reports that she used her apron as a lead rope to get the horse home.

But the faith that gave her pluck also made her gentle. The mob viciously forbade the survivors from praying, but Smith knew she needed that power more than ever: “She went out and found a shock of dried corn stalks that were tied together at the top,” says Boone, “[and] she climbed inside and called that her tabernacle. Nobody could see her, and unless they were close, they couldn’t hear her.” There Smith prayed and sang “How Firm a Foundation,” among other hymns: “The soul that on Jesus hath leaned for repose / I will not, I cannot, desert to his foes; / That soul, though all hell should endeavor to shake, / I’ll never, no never, . . . no never forsake.”

Boone becomes visibly emotional when he talks about Smith. “[She showed] incredible courage in the face of deadly force,” he says. “I have a little harder time getting through that [lecture], because man’s inhumanity to man always raises my hackles. . . . I don’t care who the underprivileged one is; it’s just not right.”

Last year Boone found Amanda Barnes Smith’s grave in Cache Valley. “It was a tender thing,” he says. “Final resting places are always sacred anyway, but to be that close to where she sleeps was really special to me.”

Jonathan Napela (1813–79): Polynesian Yoke-Mate

“Zion” in Utah was but a few years old when Elder George Q. Cannon washed up on the shores of Maui, 3,000 miles from home, without purse, scrip, or friend. The first friend he made is now a revered figure in Hawaiian Church history: Jonathan Napela.

Napela took to the gospel immediately, but his conversion cost him dearly: “He was a civilian municipal leader, a city father, a judge, a landowner,” says Professor Boone. “And most all of those he lost for the gospel’s sake.” When Napela converted, bringing many villagers with him, his peers made their disapproval clear. The rift ran so deep that eventually the gathering place for the Hawaiian Saints had to be moved from Lanai to Laie, where the temple and the BYU–Hawaii campus still stand today.

Napela was known for his faith. “One day was terribly overcast,” says Boone, “and they’d planned a conference. The missionaries were wondering if they needed to move inside because of the weather. And [Napela] came and he said, ‘Where’s your faith, elders? . . . You didn’t pray that it wouldn’t be overcast, you prayed that it wouldn’t rain. It’s not raining. Move outside.’” Boone says the rain started after the conference ended.

Napela also had the distinction of starting an unofficial MTC—in his home. He lodged the missionaries and coached them rigorously in Hawaiian. “I will provide food and shelter,” Boone paraphrases Napela, “if you will study.” This was a considerable sacrifice, since his debts exceeded his assets.

But his willingness to give of himself was most apparent when his beloved wife, Kitty Richardson Napela, contracted leprosy. At the time, Boone says, Hawaiian law made divorce extremely easy for couples in their situation, since the afflicted was quarantined—for life—in a squalid colony called Kalaupapa. Rather than abandon his sweetheart, Napela consigned himself to the same fate. He lived there as her kokua, or help, and went to work as a branch president and government liaison to improve living conditions there. Eventually Napela contracted the disease himself, dying two years before Kitty.

Perhaps one of the most remarkable aspects of his final sacrifice, says Boone, is that it is unconfirmed whether Kitty ever joined the Church or received her temple blessings. Incongruent views on faith often strike discord between spouses, but Napela never faltered in his efforts to love, support, and servehis wife.

Napela’s testimony sustained him through all trials. “It is very plain to us,” he once wrote, “that this is the Church of God, and that it is the gospel which is preached by the white men from the Rocky Mountains. There are many upon these islands who have obtained strong faith by the grace of God, through Jesus Christ the Lord, that we might receive the Holy Ghost: Amen.”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.